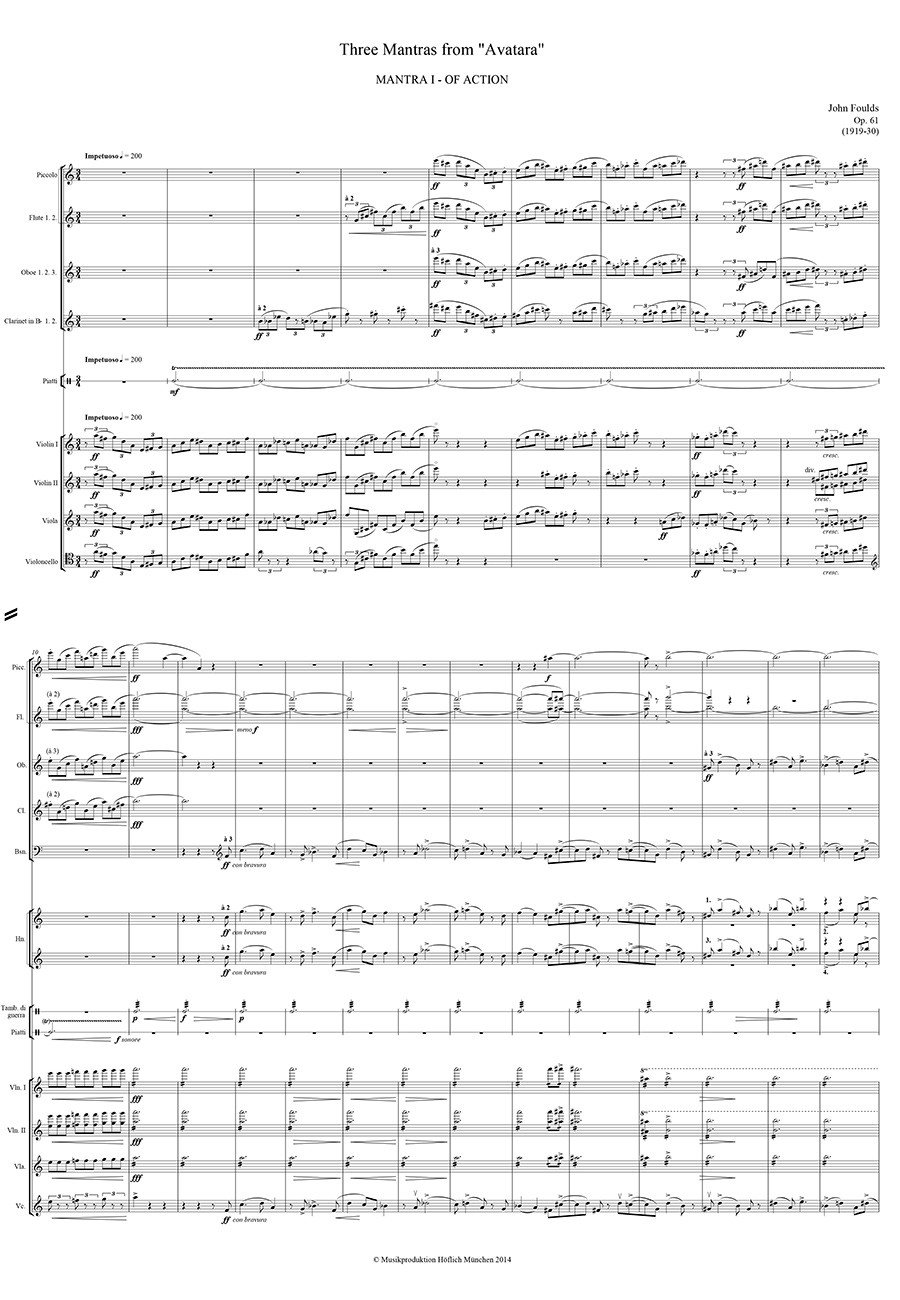

Three Mantras from Avatara Op. 61 (First printed edition, edited and engraved by Lucian Beschiu / score size 38 x 27 cm)

Foulds, John

66,00 €

Preface

John Herbert Foulds – Three Mantras from ‚Avatara’ op. 61 (1919-30)

(geb. Manchester, 2. November 1880 – gest. Kalkutta, 25. April 1939)

I Mantra of Action : Mantra and Vision of Terrestrial Avataras.

Impetuoso

II Mantra of Bliss : Mantra and Vision of Celestial Avataras.

Beatamente

III Mantra of Will : Mantra and Vision of Cosmic Avataras.

Inesorabile

John Foulds is, to my mind, perhaps the greatest twentieth-century composer of genius to be entirely ignored, not only in England, but altogether. His wholly original music exudes freedom, lightness, immediacy, and a joy of discovery capable of touching and thrilling the listener in a unique way. Foulds was at once a pioneer, a true adventurer, a comprehensive master of form, a vivacious practicing musician as a conductor, cellist, and pianist, an insatiable explorer, a prime example of unlimited stylistic versatility, a tireless innovator, and the possessor of a critical and free-thinking mind. Above all he was a man who always strove for the utmost while remaining ever cognizant of his human inadequacy. This lent him a natural modesty and enabled him to come closer and closer to his actual goal of reaching absolute freedom, of being an “enlightened one.” He found the crucial elements for his quest in Eastern culture, as handed down by the “masters of wisdom” in Central Asia and India, and sought to combine them with constructive elements of Western culture to fashion a higher unity. None of the personal setbacks and the tragic sides of his life are imposed on the listeners of his music, which invariably speaks a warm-hearted, unsentimental, and authentic language.

John Herbert Foulds was born in Manchester on 2 November 1880 as one of four children of a professional bassoon player. His ancestors were French-based Jewish bankers, one of whom, Achille Fould, rose to become Minister of Finance under Napoleon III. Foulds’s own family had little money, but indulged all the more in music, for which John revealed an early gift. He began to take piano lessons at the age of four, after which he switched to the oboe before making the cello his main instrument. His earliest compositions were produced at the tender age of seven. Little is known about him in these years except that his childhood was not very happy. He ran away from home at the age of thirteen, becoming a professional orchestral musician and undertaking journeys that took him as far afield as Vienna, where he met Bruckner. In 1900 he joined the Hallé Orchestra during it legendary period under Hans Richter.

Among Foulds’s early compositions are several string quartets, one of which, written in 1898, “tentatively experimented […] with smaller divisions than usual of the intervals of our scale, i.e. quarter-tones. Having proved in performance their practicability and their capability of expressing certain psychological states in a manner incommunicable by other means known to musicians, I definitely adopted them as an item in my composition technique.” Foulds thus became the first European composer to call for quarter-tones. However, he showed no interest in the institutionalized use of a quarter-tone scale (it is nothing but a further subdivision of the artificial well-tempered semitonic scale) and always openly criticized its misuse: “The effect therefore is somewhat as if a poet should retell the old, old story of Cinderella in words every one of which should contain a ‘th’.” Time and again we find, in Foulds’s slow movements, polished quarter-tone passages conveying a strange sensation of wildness and splendid irregularity. His tone-poem Mirage of 1910 is an early example of such music. It was preceded by Foulds’s first major success, when Henry Wood premièred his Epithalamium (op. 10) at the Queen’s Hall Proms in 1906. Several long passages of Mirage clearly reveal the influence of Richard Strauss, who is equaled only by Edward Elgar as the obviously formative figure in Foulds’s early style. His elaborate sense of timbre is already well-developed in these early works, which constantly invite comparison with the subtleties of French orchestration.

Why did John Foulds remain so unknown? The reasons are many and varied. A not inconsiderable voice on the English music scene, he refused to mince words in his criticism, regardless of the stature of the figures he criticized. More seriously, he soon had to support a family and needed more than the meager proceeds he obtained from his activities in “art music.” Thus, to make ends meet, he also turned out “light music,” writing highly successful pieces in this genre. At times this led to a considerable output of peripheral music that eclipsed his essential works. Soon practically the only music of his that reached performance was his light music, which, be it said, was among the best and most polished in the trade (the most successful piece was Celtic Lament, which exists in myriad arrangements). Until a few years ago Foulds was still categorized as a “light-music composer” at the BBC. The resurgent interest in his music is due mainly to the tireless efforts of the Scottish musicologist Malcolm MacDonald (1948-2014), on whose superb biography John Foulds and His Music (London: Kahn & Averill, 1989) the present preface is based.

In 1915 Foulds met the woman of his life in London: Maud MacCarthy (1882-1967). She had grown up as a violin prodigy, but was prevented by a nervous disorder from continuing her career. Instead, she had developed a consuming interest in Indian music and the world of spiritualism, in esoteric and occult practices. She traveled in 1909 to India, where she collected folk melodies and spent two years studying Indian art music. She also learned to play several instruments and effortlessly sang the traditional micro-intervallic scales. In 1915 she taught Foulds the rudiments of playing the tabla; later he would learn to play the vina, and his interest in exotic tonal systems was directed into systematic channels. He created a table of ninety modes, all of which he considered equal in value to the surviving two modes favored in Western music, major and minor. Inspired by the example of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, he planned to produce several sets of studies in all the modes, but was only able to produce the first seven of these Essays in the Modes. An eighth, entitled Dynamic Mode, became the opening movement of his piano concerto Dynamic Triptych. Foulds placed great store in the pure and unalloyed use of modes, being convinced that they could only attain maximum effect if left unaltered and devoid of alien elements. He sharply criticized that then customary chromatic harmonization of modal melodies, which neutralize the essential, idiomatic character and charm of the melodic writing, and instead sought pure solutions, an elaborate and synthetic simplicity surpassing the stage of needless complexity. Unlike later explorers of modality, such as Messiaen, Foulds did not consider all scales formally viable; indeed, to him they were not even “modes” at all. Among them were the total chromaticism of the twelve-tone row and any scale without a pure fifth, including the whole-tone scale: “It will be observed that every mode in this table contains an invariable dominant in addition to the tonic. Modes exist by reason of the relation of their component notes to a tonic, and in only slightly lesser degree (to my ear) by the stabilizing influence of the dominant. Once this latter is withdrawn or tampered with (i.e. either flattened or sharpened), the mode, as such, completely disintegrates. It is in just this quality of concentration that the value of the modes inheres.” Here, for all his joy of discovery, Foulds proves to be an incorruptible advocate of natural tonality – of the life-imparting oscillation between tension and release in the articulation of harmony, of hierarchic tonal relations surrounding a central pitch, and of the character of modes as specific combinations of pitches surrounding a tonic epicenter, which serves as a harmonic fulcrum and pivot. Though he viewed atonality as an important achievement in the modern composer’s arsenal, he rejected its systematic application and referred to the complete absence of personality in the music of most adherents of the dodecaphonic school: “And if the persistent atonalist assert that this system is the appropriate expression of all the heights and depths his consciousness is able to contact, I can only make the rejoinder that he is no great traveller.”

From 1919 to 1921 Foulds worked on one of his central works, A World Requiem, based on Christian and Hindu texts. During these labors he fell again and again into a state he described as “clairaudient,” his personal recasting of the word “clairvoyant” as related to the aural faculty. It is said that he and Maud could receive the same melodies simultaneously. A World Requiem, involving up to 1,200 vocalists, seems to have taken hold in Royal Albert Hall as an annual ritual on Armistice Night, the future Festival of Remembrance. In its dignified and unadorned magnificence, it was a work that moved large audiences to tears and thrilled them with excitement. But the great success and incontestable grandeur of a work positioned between every stool attracted envy and intrigues, and its fourth performance, in 1926, proved to be the last. One year later Foulds moved to Paris, where he devoted himself to the composition of his Essays in the Modes, his piano concerto Dynamic Triptych, and the completion of his magnum opus, the opera Avatara. In these years he also made lesser excursions into realms of simple statements, including the string composition Hellas – a Suite of Ancient Greece (op. 45), which was not completed until 1932.

Foulds’s most significant creation was the opera Avatara, probably a Krishna opera set in India. He worked on it from 1919 to 1930, but before completing the third and final act he evidently realized that the material was not suitable for operatic treatment. He then extracted the preludes to the three acts from the overall score, giving them the title Three Mantras from Avatara. The rest of the work has eluded rediscovery and may have been destroyed by the composer.

By the time Foulds returned to London in 1930 he had already been thoroughly discredited in England. He could not even find a publisher for his orchestration of Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” Quartet. In 1934 the firm of Nicholson & Watson published his book Music To-Day, an artistic and spiritual credo to which he assigned the opus number 92. He promised the publishers to submit a sequel on Indian music, but his wife, under the influence of the medium William Coote (a.k.a. “The Boy”), persuaded him to travel to India. Thus, on 25 April 1935 Foulds set sail for India, accompanied by his wife, two children, and “The Boy,” completing his Indian Suite for orchestra during the passage. A few months later he received, from his friend George Bernard Shaw, a postcard containing a single question: “What the devil are you doing in India?”

What did Foulds do in India? At first he traveled, especially in Punjab and Kashmir, to carry on his research into folk music. In 1937 he became head of European music at All-India Radio in Delhi, where he delivered a legendary broadcasting series entitled “Orpheus Abroad” and began to rehearse with Indian musicians on their instruments. With unquenchable gusto he taught each and every one of these musicians to read music and instructed them in ensemble playing, composing simple pieces for their use. On 28 March 1938 the first presentable results of this collaboration between a western orchestra and a group of Indian musicians were performed in public in the presence of the Viceroy. Besides founding the Indo-European Orchestra, Foulds also continued with undiminished energy to produce demanding compositions. He completed two Pasquinades Symphoniques, and on 10 March 1939 his Symphonic Studies for Strings was premièred in Bombay. Foulds had ambitious plans and worked to fulfill his lifelong dreams for the benefit of all mankind. When he was offered a high-level position in the newly founded radio station in Calcutta, he ignored his wife’s advice and accepted the offer, hoping to obtain greater freedom to carry out his bold ideas for uniting the peoples of the world: West meets East!

Immediately after arriving in Calcutta Foulds suddenly took ill. In the critical moments there was no one nearby in his hotel, and by the time his screams of pain drew attention it was already too late. Caught in the advanced stage of Asiatic cholera, he was taken to hospital, where he died a few hours later in the night between 24 and 25 April 1939. No familiar face was nearby, and no one was willing or able to continue the work he had begun. India was rushing toward independence, and the Second World War eclipsed everything that had gone before.

Foulds’s widow, Maud MacCarthy, married “The Boy” and became the first woman to rise to the full rank of sannyasa. With unfaltering care she preserved the few Foulds manuscripts she was able to secure and took them with her in the late 1950s when she returned to Europe, where she died on the Isle of Man in 1967. But most of Foulds’s late works are lost, including Deva-Music, Symphony of East and West, the Symphonic Studies for Strings, and four of the five movements from his final string quartet. After Maud MacCarthy’s death many years had to pass before, in the 1980s, posterity tentatively began to discover what genius and vibrancy lay dormant in his surviving manuscripts. There are still many mysteries to be disclosed and discoveries to be made in the personality and music of John Foulds.

We owe the (re)discovery of John Foulds to two people in particular. With unerring musical instinct, Malcolm MacDonald has spent years of his scholarly abilities in the service of researching and describing Foulds’s life, character, and music, and has tirelessly devoted himself for decades to the dissemination of this knowledge (moreover, given the breadth of his scholarship, he is anything but a specialist). Graham Hatton, the publisher of the music of John Foulds and Havergal Brian (another much underrated composer on whom MacDonald has written several books), has with meticulous care (and in highly unfavorable economic conditions) laid the groundwork for solid performance material. Hatton is a true idealist who has never doubted that his services on behalf of great but forgotten composers have been worth the sacrifices he has made. Though his heirs transferred the performance material of Brian’s music to a larger publisher in the 1990s, Hatton remains the person to whom anyone interested in performing Foulds can and must reliably turn.

As an orchestral composer John Foulds is one of the outstanding figures of classical modernism with regard both to his inspiration and stylistic self-assurance and to his technical mastery of the orchestra as a whole. This is true whether the works were originally conceived for orchestra or represent arrangements of music composed for a different medium. In the latter respect his mastery is comparable in every way to that of a Maurice Ravel: the pieces sound as if they originated in orchestral garb and betray no hint of academicism, superbly adapting the features, balance, and quality in a structure of wide-ranging dynamics and color-contrasts. His first important work for orchestra, the music-poem Epithalamium (op. 10, 1905-06), was followed in 1908-09 by the great Cello Concerto in G (op. 17) and his second music-poem Apotheosis: Elegy in Memory of Joseph Joachim for violin and orchestra (op. 18). With his third music-poem, Mirage for full orchestra (op. 20, 1910), he produced what was then his most substantial, progressive, and significant orchestral work with regard to style, compositional fabric, and program. The years that followed, particularly beginning in the 1920s, witnessed the creation of an extremely large, highly varied, and brilliantly nuanced body of orchestral music, of which perhaps half has unfortunately disappeared. This music, the product mainly of his work as a theater composer and an extremely versatile creator of high-caliber “light music,” has come down to us notably in the two series of Music Pictures, [Group 3] for orchestra (op. 33, 1912) and [Group 4] for string orchestra (op. 55, 1917); his incidental music for George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (op. 82, 1924), which he also boiled down into a captivating suite; the gigantic part for full orchestra in his concert-opera The Vision of Dante after Dante’s Divine Comedy (op. 7, 1905-08); and, above all else, A World Requiem (op. 60, 1919-21).

The most ambitious of Foulds’s surviving orchestral works were written in the late 1920s: the grandiose piano concerto Dynamic Triptych (op. 88, 1929), and his most radical creation for large forces, Three Mantras (op. 61b, 1919-30) from the opera Avatara (op. 61, 1919-32), which he abandoned in the third act and then presumably destroyed. Most of the orchestral pieces that he went on to write later, especially those he composed in India from 1935 on, are unfortunately lost. The few that have survived, such as his orchestration of Franz Schubert’s String Quartet “Der Tod und das Mädchen” (1930), the enlarged orchestral version of the piano piece April-England of 1926 (1932), the two completed Pasquinades Symphoniques (op. 98, 1935; the third, Modernist, was left unfinished), and the short ostinato piece The Song of Ram Dass for small orchestra (1935), are of supreme polish, bold craftsmanship, and, in the simple movements, unsurpassable beauty.

Three Mantras from “Avatara,” op. 61

The most ambitious project in John Foulds’s creative output was undoubtedly his three-act opera Avatara, its only comparable predecessors being the concert-opera The Vision of Dante (op. 7, ca. 1905-08) and A World Requiem (op. 60, 1919-21). The initial sketches were begun in Penn, Buckinghamshire, on 18 August 1919, shortly after he had started work on A World Requiem, which would occupy him for the next two years until its completion. The sketches involve rough versions of the themes for the first and third Mantras. For the second, Foulds merely wrote a verbal description of its opening: “Beginning with a long sustained note in middle register (as I always hear music) then the trills and exchanges, these spreading over to higher & lower octaves, then the overtones, & the ‘exquisite inter-tracery’ of the ‘Consilium Angelicum.’” (Malcolm MacDonald maintained that the Consilium Angelicum, which bore the opus number 62, one greater than Avatara, was probably a book rather than a piece of music. As the work has vanished completely, there is no way of determining precisely what the reference applies to.)

The preludes to the three acts were originally meant to bear the titles Apsara Mantra, Gandharva Mantra, and Rakshasa Mantra. Owing to the vast multitude of Hindu (and later Buddhist) traditions regarding the supernatural beings invoked in these titles, we cannot say for certain what Foulds intended to depict. The apsaras, for instance, are generally demi-goddesses; the gandharvas are beings of the sun or the firmament whose existence gives rise to celestial music (later the gandharva music received more rigorous rituals and formed one of the main resources of classical Indian music); and the rakshasas are usually terrifying demons of various shapes and sizes. Such characteristics of these beings as are perceivable to humans range from temptation via danger and annihilation to protection and enlightenment.

Between 1923 and 1926, Foulds became a public figure as a result of the rousing success of his sublime and transcendent masterpiece, A World Requiem. In 1924-25 he wrote, among other things, incidental music for George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, Ernst Toller’s Masse Mensch, Euripides’ Hippolytus, and Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Of these scores, the concert suite version of Saint Joan is undoubtedly one of his most riveting orchestral works. The year 1926 witnessed several smaller piano pieces. April-England, one of his most beautiful and vivacious creations, was written down on the morning of 21 March 1926, the day of the spring equinox. As he noted: “Such moments as those of the Solstices and Equinoxes always seem to be particularly potent to the creative artist, and no less significant the place in which he happens to be at such time.”

It was probably not until 1926 that Foulds began to orchestrate Avatara, which at this time still bore the working title Avatar. In Sanskrit, avatara refers to a manifestation of the divine principle, or an aspect of the same in the form of an animal or human being. It literally means “to descend” (ava = downward, tar = to cross). To Theosophists, whose influence informed Foulds’s interest in the world of India, avatara is simply an incarnation of the divine. Avatars, such as Krishna, return in different eras in order to provide guidance in dark times to human beings, whose purpose in life is to turn toward the divine.

A mantra is a sound, word, or line of verse that is charged with spiritual force and makes it possible, usually through ceaseless repetition, to perceive the infinite (the divine principle) in a transient world. It thereby allows the Here and Now to be experienced as a manifestation of the measureless Beyond, and the passage of time as a manifestation of the eternity inherent in any moment. In his fundamental book Music To-Day, published by Ivor Nicholson & Watson in London as his op. 92 (1934), Foulds defined “mantra” as “a short rhythmic arrangement either of words or musical sounds of an evocative nature, which, when constantly repeated – in conformity with laws not generally known but as definite as a mathematical formula – set going causes which produce predictable results.”

Not only has the music of Avatara disappeared (apart from the three preludes), the libretto too has vanished without a trace. All that survives regarding the title, besides the translation of the word avatara from the Sanskrit on the title page of the Mantras, is the note “A descent into – incarnation in – or manifestation upon earth, of deity.” Another inscription, dated September 1926, reads “Sanatana Dharma, Benares 1902” (Malcolm MacDonald surmised that this may be a bibliographical reference to a 1902 publication from the Hindu University in Benares). Sanatana Dharma refers to the eternal and immutable cosmic order in which all the events in all the worlds have been grounded since time immemorial and for all eternity.

On 20 September 1928, E. B. Havell (1861-1938), an authoritative orientalist from Headington, Oxford, and the founder of the Calcutta School of Art, wrote a letter to the secretary of the Maharajah of Baroda in which he introduced John Foulds and Maud MacCarthy. In it he described Foulds as “an eminent musical composer and conductor who is at work on a grand opera on the subject of Sri Krishna, [who] would very much appreciate any assistance and advice H.H. the Maharaja could give him in making the music a true expression of Indian musical thought and in showing the way for a musical renaissance in India.” MacDonald concluded that by this time Foulds and MacCarthy were looking for ways to travel to India. The letter is evidence that Avatara was an opera on Krishna, and that Foulds, long before his final relocation to India, had nourished plans that he was only able to realize in 1935.

The main work on Avatara fell in a period when Foulds, after his dismaying experiences in London (especially the ignorant dropping of his successful World Requiem from the repertoire), saw no future for his music in England and moved via Taormina to Paris, where he was active from 1927 to 1930. This period brought forth such magnificent works as the Essays in the Modes, the piano concerto Dynamic Triptych, and the orchestral version of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden quartet. He continued his work on Avatara in the first year after his return to London in 1930.

Given the lack of sources and statements, the reasons that ultimately led Foulds to extract the three preludes from the score of his opera, which he continued to compose at least until the completion of the third Mantra in 1930, can only be a matter of guesswork. In his handwritten score of Three Mantras, subsequently bound together in a single volume, the movements still have the original page numbers they received as part of the opera. Thus, Mantra of Action occupies pages 1 to 33 in the manuscript, Mantra of Bliss pages 212 to 240 (the ending still includes the first bar of transition to the stage action), and Mantra of Will pages 392 to 421. Of course the possibility has been mooted that Foulds was persuaded (or came independently to the realization) that an opera about a holy man was an act of blasphemy. Now, it is perfectly safe to assume that Avatara was not an opera in the conventional sense, but something akin to a mystery play, without suggesting that it was in any way similar to Wagner’s Parsifal, Enescu’s Œdipe, Szymanowski’s Krol Roger, or similar reworkings of mystical subjects. It is also perfectly conceivable that Foulds, at some point, came to realize that it is simply impossible to lend adequate musical expression to the transcendent material. We do not know whether he (or, after his death, Maud MacCarthy) destroyed the score of the opera after extracting the three preludes, or whether, as so often in his case, an unfortunate chain of circumstances caused it to go missing, or to be devoured by rats or termites in India. All that Malcolm MacDonald could conclude from this maze of questions was that Foulds in all likelihood completed the third Mantra after 1930, but not the third act, and that approximately four-fifths of the finished music is no longer extant. To my mind, Foulds most probably came to grief trying to complete the third act and then jettisoned the opera at some point, after which he extracted the Mantras and combined them to form an independent composition. Whatever the case, he had not yet entirely abandoned his plan to complete Avatara in 1934, when his Music To-Day: Its Heritage from the Past, and Legacy to the Future appeared in print, for the book explicitly mentions the opera. But it has nothing to say about the opera’s plot or musical design.

Although the Avatara opera is lost, and with it the original context of Three Mantras, the three pieces definitively handed down by Foulds as a three-movement orchestral work form a strikingly coherent unity in the manner of a three-movement symphony – a unity additionally reinforced by motivic cross-relations and transformations spread across the movements like a web of leitmotifs. In Music To-Day, Foulds presented the key discovery that appears to be the only possible point of departure for what he called an “objective aesthetic”: an ancient classification scheme, derived from the Sanskrit, of the seven dimensions of consciousness permeating the entire universe. These seven dimensions are identical even in the subtlest gradations with the seven-fold nafs scale of naqshbandi Sufism, and thus, incidentally, constitute clear proof that the exploration of universal consciousness, within which human consciousness represents but one possibility, has common Asiatic origins.

As we have seen, the five lower dimensions are referred to as “manifest,” the two upper ones as “unmanifest.” From the writings of Sufism it transpires that the “unmanifest” dimensions of consciousness are those which lie beyond reach of the human mind in our present era. Human beings operate almost exclusively in the two lowest dimensions and in the lower region of the third dimension. We speak of nascent enlightenment when a human being comes into contact with the higher region of the third dimension. All of this seems highly schematic, at least to anyone marked by Western culture, and stands in need of a brief explanation. The task of the explanation is, first, to emphasize that the strict separations between the dimensions are not so sharp in reality as the system seems to imply, and that there is an infinite variety of distinctions within each dimension. When consciousness has its emphasis in a higher dimension, this does not mean that the lower dimensions no longer play a role or are abandoned. It merely means that they no longer have a governing role in human action and are placed in the service of the higher ones.

The lowest dimension, sthula, corresponds to what the Sufis refer to as ammara. It is the plane of pure physical existence, which is also the plane of unrestrained egoism. Its outstanding quality is vitality, primitive force, accompanied by the fundamental forces of greed, fear, and sloth (two antithetical but mutually conditioned forces, and a neutral force) which ensures that no development takes place. This is the plane of the “survival of the fittest.” …

Ganzes Vorwort lesen > HIER

Score Data

| Special Edition | Foulds Edition |

|---|---|

| Genre | Chor/Stimme & Orchestra |

| Seiten | 110 |

| Special size | 270 x 380 mm |

| Performance materials | available |

| Printing | First print / Urtext |

| Size | 270 x 380 mm |