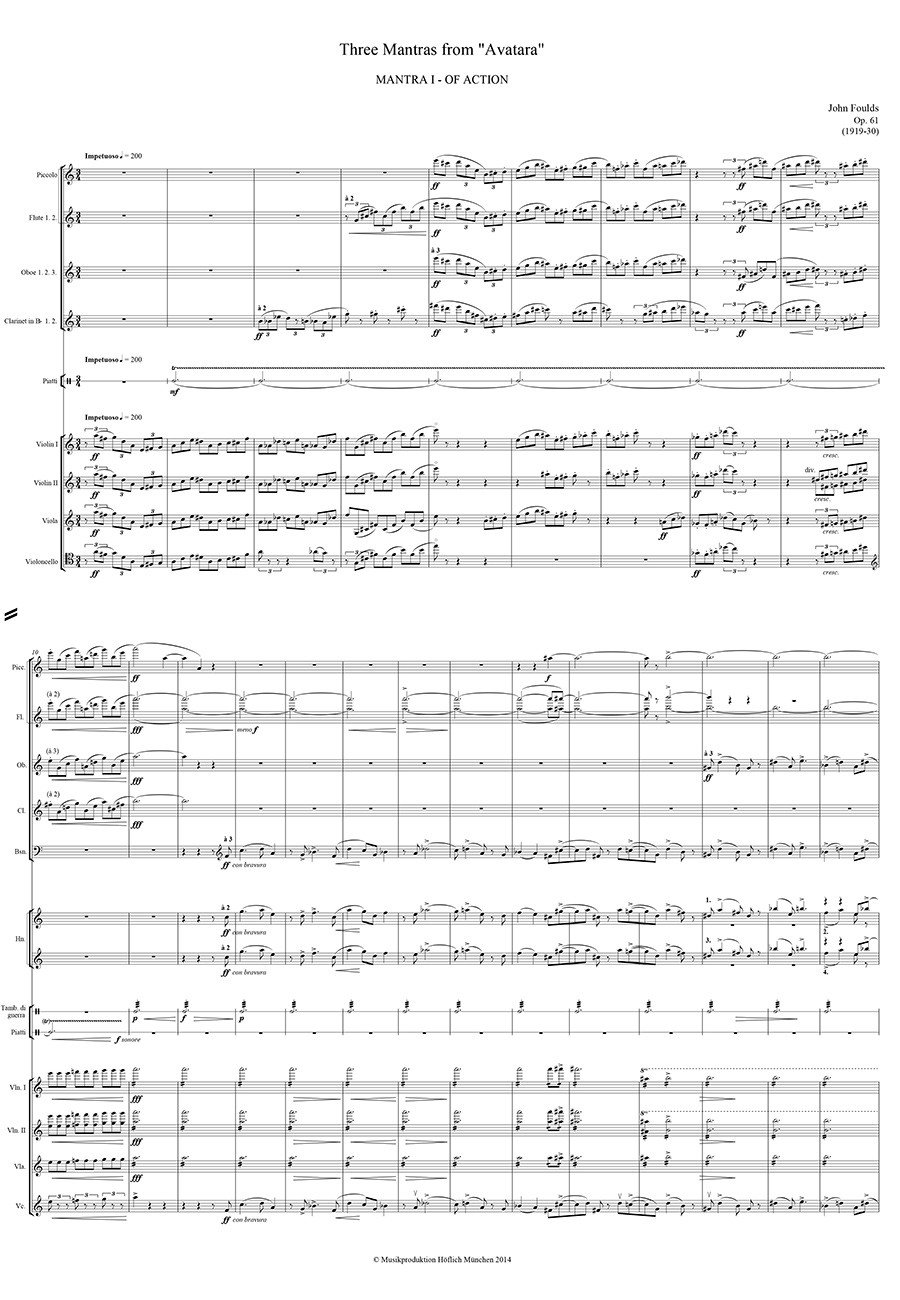

Three Mantras from ‚Avatara’ Op. 61 (First printed edition, edited and engraved by Lucian Beschiu / score size 38 x 27 cm)

Foulds, John

66,00 €

Preface

John Herbert Foulds

Three Mantras from ‚Avatara’ op. 61 (1919-30)

(geb. Manchester, 2. November 1880 – gest. Kalkutta, 25. April 1939)

I Mantra of Action : Mantra and Vision of Terrestrial Avataras.

Impetuoso

II Mantra of Bliss : Mantra and Vision of Celestial Avataras.

Beatamente

III Mantra of Will : Mantra and Vision of Cosmic Avataras.

Inesorabile

The most ambitious project in John Foulds’s creative output was undoubtedly his three-act opera Avatara, its only comparable predecessors being the concert-opera The Vision of Dante (op. 7, ca. 1905-08) and A World Requiem (op. 60, 1919-21). The initial sketches were begun in Penn, Buckinghamshire, on 18 August 1919, shortly after he had started work on A World Requiem, which would occupy him for the next two years until its completion. The sketches involve rough versions of the themes for the first and third Mantras. For the second, Foulds merely wrote a verbal description of its opening: “Beginning with a long sustained note in middle register (as I always hear music) then the trills and exchanges, these spreading over to higher & lower octaves, then the overtones, & the ‘exquisite inter-tracery’ of the ‘Consilium Angelicum.’” (Malcolm MacDonald maintained that the Consilium Angelicum, which bore the opus number 62, one greater than Avatara, was probably a book rather than a piece of music. As the work has vanished completely, there is no way of determining precisely what the reference applies to.)

The preludes to the three acts were originally meant to bear the titles Apsara Mantra, Gandharva Mantra, and Rakshasa Mantra. Owing to the vast multitude of Hindu (and later Buddhist) traditions regarding the supernatural beings invoked in these titles, we cannot say for certain what Foulds intended to depict. The apsaras, for instance, are generally demi-goddesses; the gandharvas are beings of the sun or the firmament whose existence gives rise to celestial music (later the gandharva music received more rigorous rituals and formed one of the main resources of classical Indian music); and the rakshasas are usually terrifying demons of various shapes and sizes. Such characteristics of these beings as are perceivable to humans range from temptation via danger and annihilation to protection and enlightenment.

Between 1923 and 1926, Foulds became a public figure as a result of the rousing success of his sublime and transcendent masterpiece, A World Requiem. In 1924-25 he wrote, among other things, incidental music for George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, Ernst Toller’s Masse Mensch, Euripides’ Hippolytus, and Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Of these scores, the concert suite version of Saint Joan is undoubtedly one of his most riveting orchestral works. The year 1926 witnessed several smaller piano pieces. April-England, one of his most beautiful and vivacious creations, was written down on the morning of 21 March 1926, the day of the spring equinox. As he noted: “Such moments as those of the Solstices and Equinoxes always seem to be particularly potent to the creative artist, and no less significant the place in which he happens to be at such time.”

It was probably not until 1926 that Foulds began to orchestrate Avatara, which at this time still bore the working title Avatar. In Sanskrit, avatara refers to a manifestation of the divine principle, or an aspect of the same in the form of an animal or human being. It literally means “to descend” (ava = downward, tar = to cross). To Theosophists, whose influence informed Foulds’s interest in the world of India, avatara is simply an incarnation of the divine. Avatars, such as Krishna, return in different eras in order to provide guidance in dark times to human beings, whose purpose in life is to turn toward the divine.

A mantra is a sound, word, or line of verse that is charged with spiritual force and makes it possible, usually through ceaseless repetition, to perceive the infinite (the divine principle) in a transient world. It thereby allows the Here and Now to be experienced as a manifestation of the measureless Beyond, and the passage of time as a manifestation of the eternity inherent in any moment. In his fundamental book Music To-Day, published by Ivor Nicholson & Watson in London as his op. 92 (1934), Foulds defined “mantra” as “a short rhythmic arrangement either of words or musical sounds of an evocative nature, which, when constantly repeated – in conformity with laws not generally known but as definite as a mathematical formula – set going causes which produce predictable results.”

Not only has the music of Avatara disappeared (apart from the three preludes), the libretto too has vanished without a trace. All that survives regarding the title, besides the translation of the word avatara from the Sanskrit on the title page of the Mantras, is the note “A descent into – incarnation in – or manifestation upon earth, of deity.” Another inscription, dated September 1926, reads “Sanatana Dharma, Benares 1902” (Malcolm MacDonald surmised that this may be a bibliographical reference to a 1902 publication from the Hindu University in Benares). Sanatana Dharma refers to the eternal and immutable cosmic order in which all the events in all the worlds have been grounded since time immemorial and for all eternity.

On 20 September 1928, E. B. Havell (1861-1938), an authoritative orientalist from Headington, Oxford, and the founder of the Calcutta School of Art, wrote a letter to the secretary of the Maharajah of Baroda in which he introduced John Foulds and Maud MacCarthy. In it he described Foulds as “an eminent musical composer and conductor who is at work on a grand opera on the subject of Sri Krishna,

[who] would very much appreciate any assistance and advice H.H. the Maharaja could give him in making the music a true expression of Indian musical thought and in showing the way for a musical renaissance in India.” MacDonald concluded that by this time Foulds and MacCarthy were looking for ways to travel to India. The letter is evidence that Avatara was an opera on Krishna, and that Foulds, long before his final relocation to India, had nourished plans that he was only able to realize in 1935.

The main work on Avatara fell in a period when Foulds, after his dismaying experiences in London (especially the ignorant dropping of his successful World Requiem from the repertoire), saw no future for his music in England and moved via Taormina to Paris, where he was active from 1927 to 1930. This period brought forth such magnificent works as the Essays in the Modes, the piano concerto Dynamic Triptych, and the orchestral version of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden quartet. He continued his work on Avatara in the first year after his return to London in 1930.

Given the lack of sources and statements, the reasons that ultimately led Foulds to extract the three preludes from the score of his opera, which he continued to compose at least until the completion of the third Mantra in 1930, can only be a matter of guesswork. In his handwritten score of Three Mantras, subsequently bound together in a single volume, the movements still have the original page numbers they received as part of the opera. Thus, Mantra of Action occupies pages 1 to 33 in the manuscript, Mantra of Bliss pages 212 to 240 (the ending still includes the first bar of transition to the stage action), and Mantra of Will pages 392 to 421. Of course the possibility has been mooted that Foulds was persuaded (or came independently to the realization) that an opera about a holy man was an act of blasphemy. Now, it is perfectly safe to assume that Avatara was not an opera in the conventional sense, but something akin to a mystery play, without suggesting that it was in any way similar to Wagner’s Parsifal, Enescu’s Œdipe, Szymanowski’s Krol Roger, or similar reworkings of mystical subjects. It is also perfectly conceivable that Foulds, at some point, came to realize that it is simply impossible to lend adequate musical expression to the transcendent material. We do not know whether he (or, after his death, Maud MacCarthy) destroyed the score of the opera after extracting the three preludes, or whether, as so often in his case, an unfortunate chain of circumstances caused it to go missing, or to be devoured by rats or termites in India. All that Malcolm MacDonald could conclude from this maze of questions was that Foulds in all likelihood completed the third Mantra after 1930, but not the third act, and that approximately four-fifths of the finished music is no longer extant. To my mind, Foulds most probably came to grief trying to complete the third act and then jettisoned the opera at some point, after which he extracted the Mantras and combined them to form an independent composition. Whatever the case, he had not yet entirely abandoned his plan to complete Avatara in 1934, when his Music To-Day: Its Heritage from the Past, and Legacy to the Future appeared in print, for the book explicitly mentions the opera. But it has nothing to say about the opera’s plot or musical design. …

Read complete preface > HERE

Score Data

| Special Edition | Foulds Edition |

|---|---|

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Pages | 110 |

| Special size | 270 x 380 mm |

| Performance materials | available |

| Printing | First print / Urtext |

| Size | 270 x 380 mm |

| Special Size | 270 x 380 mm |