La Lyre et la Harpe Op. 57, cantata for orchestra, SATB choir, and SATB soloists (with French & German libretto)

Saint-Saëns, Camille

42,00 €

Preface

Camille Saint-Saëns – La lyre et la harpe. Cantata for orchestra, SATB choir, and SATB soloists, Op. 57 (1879)

(b. Paris, 9 October 1835 – d. Algiers, 16 December 1921)

Preface

Camille Saint-Saëns is best known today for his charming orchestral work Le carnaval des animaux and the melodramatic opera Samson et Dalila. Although the subjects of these two pieces differ widely—the first programmatically depicts well-known creatures while the second recounts a famous Biblical story—both are approachable and familiar for a Western audience, which may be part of the reason for their enduring popularity.

A lesser-known piece of Saint-Saëns’s serves as a better entry into the composer’s creative world. His thirteen-movement cantata La lyre et la harpe focuses on some of the most important ideas in French Romanticism: faith, love, death, and the function of the artist in the world. Based on Victor Hugo’s 1822 poem of the same name, it was the first piece by a French composer commissioned for the Birmingham Festival, demonstrating Saint-Saëns’s stature in the musical world at that time.

In Hugo’s poem, the Lyre (representing Greco-Roman paganism) and the Harp (representing Christianity) take turns trying to convince a poet to follow their respective worldviews—in the end, the poet decides both philosophies can be used in artistic works. In the nineteenth century, paganism and Catholicism coexisted in France; increased scholarly and artistic interest in Greece and Rome also broadened the dialogue about non-Catholic worship traditions.1 Hugo’s works critiqued the ruling classes, including the monarchy and Catholic leaders, as in famous villainizations of Claude Frollo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) and Inspector Javert in Les Misérables (1862). Instead, he elevated downtrodden, anti-royalist Frenchmen like those who incited the French Revolution.

In setting Hugo’s text, Saint-Saëns demonstrated that he shared these anti-Catholic and anti-royalist beliefs of Post-French Revolution Romantics, but Saint-Saëns also had a deep academic interest in the ancient world. He published essays about the Roman lyre and theatrical traditions based on studies of ancient Roman art. Saint-Saëns believed in the importance of large performing forces in spacious venues.2

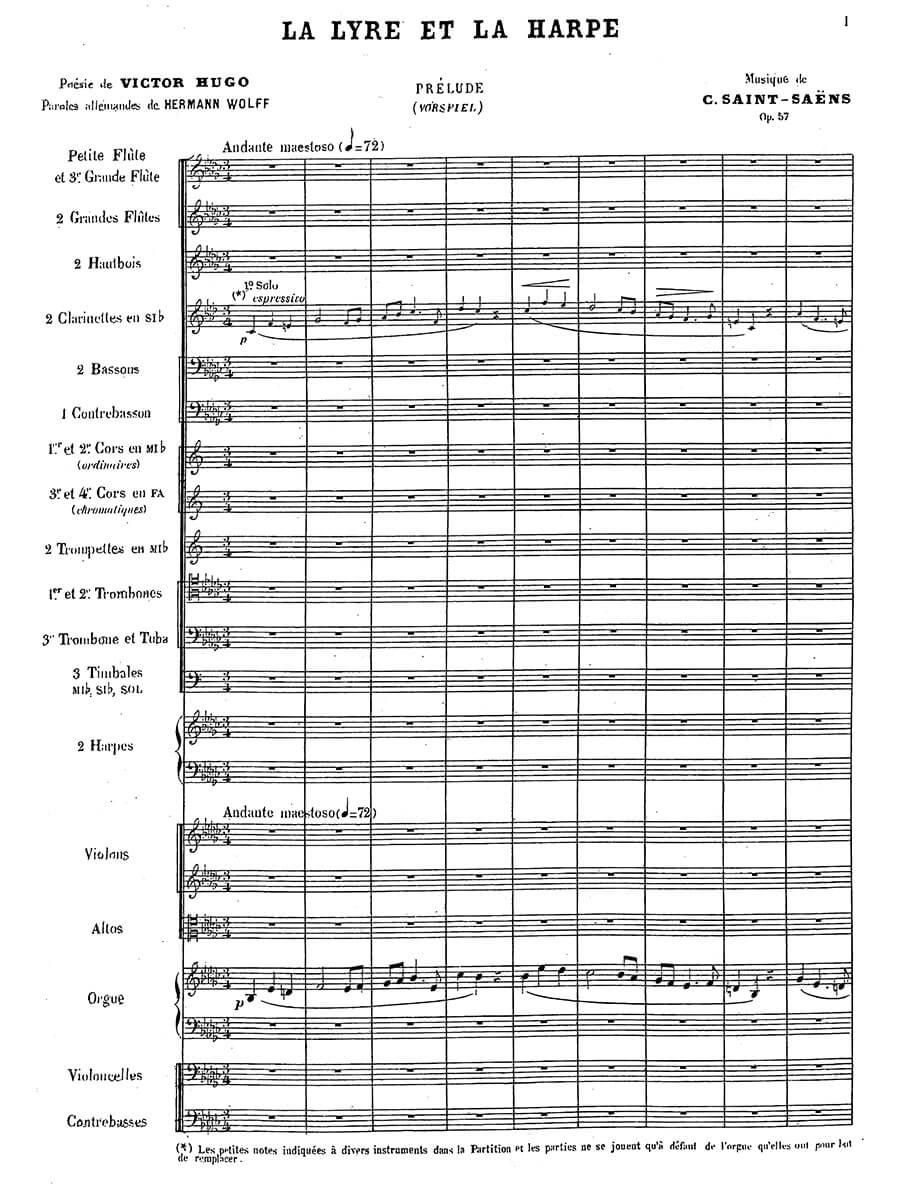

La lyre et la harpe consists of a prelude and twelve movements. Saint-Saëns conducted the first performance in Birmingham in August 1879, leading a group of 500 musicians. Saint-Saëns’s setting of Hugo’s poem elaborates on the core idea that Greco-Roman and Christian philosophies can coexist as they did in France in his time. The work is orchestrated for SATB choir, SATB soloists, and full orchestra. Through careful use of key areas, thematic material, and textures Saint-Saëns unites the movements symmetrically with No. 7, which combines Harp and Lyre text, as the center point of the work. The Prelude, No. 7, and the Epilogue’s joining of musical and poetic material from the two characters clearly shows Hugo’s idea that the Lyre and Harp philosophies can coexist.

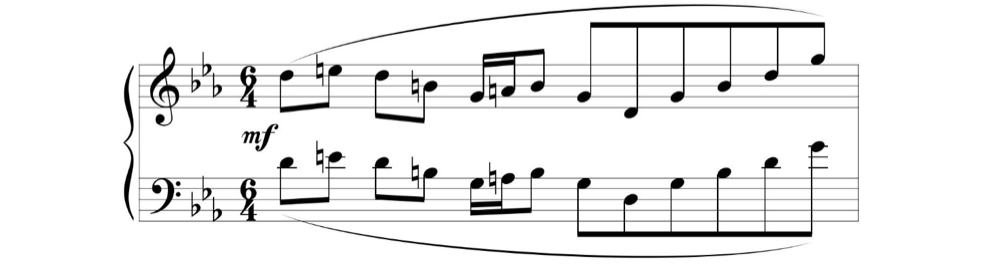

Saint-Saëns consistently contrasts the Lyre and Harp movements using textural differences. The ABAB form Prelude sets up the textural dichotomy, switching from solo organ in the Harp sections to thicker orchestral texture in the Lyre sections. The Harp movements use a sparse orchestral texture. The Harp theme that opens the Prelude (Example 1) is played quietly on solo organ, perhaps harkening to the style of Catholic church organists. Most movements from the Harp’s perspective are sung without the choir. Only one, No. 6, includes choir, but it is in support of a tenor soloist.

Example 1: Prelude, La lyre et la harpe, Organ, mm. 1-4, “Harp theme”

The Lyre theme (Example 2) appears in the harps because they are the closest orchestral instrument to the ancient lyre in timbre. Saint-Saëns makes a textural contrast between the Harp and Lyre sections by involving the choir in all but two of the Lyre movements. This use of choir coupled with consistent full orchestra could reference the composer’s impression that Greco-Roman theatre included large choruses and attracted large audiences. …

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 194 |