Camille Saint-Saëns

(b. Paris, 9 October 1835 – d. Algiers, 16 December 1921)

La lyre et la harpe

Cantata for orchestra, SATB choir, and SATB soloists, Op. 57 (1879)

Preface

Camille Saint-Saëns is best known today for his charming orchestral work Le carnaval des animaux and the melodramatic opera Samson et Dalila. Although the subjects of these two pieces differ widely—the first programmatically depicts well-known creatures while the second recounts a famous Biblical story—both are approachable and familiar for a Western audience, which may be part of the reason for their enduring popularity.

A lesser-known piece of Saint-Saëns’s serves as a better entry into the composer’s creative world. His thirteen-movement cantata La lyre et la harpe focuses on some of the most important ideas in French Romanticism: faith, love, death, and the function of the artist in the world. Based on Victor Hugo’s 1822 poem of the same name, it was the first piece by a French composer commissioned for the Birmingham Festival, demonstrating Saint-Saëns’s stature in the musical world at that time.

In Hugo’s poem, the Lyre (representing Greco-Roman paganism) and the Harp (representing Christianity) take turns trying to convince a poet to follow their respective worldviews—in the end, the poet decides both philosophies can be used in artistic works. In the nineteenth century, paganism and Catholicism coexisted in France; increased scholarly and artistic interest in Greece and Rome also broadened the dialogue about non-Catholic worship traditions.1 Hugo’s works critiqued the ruling classes, including the monarchy and Catholic leaders, as in famous villainizations of Claude Frollo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) and Inspector Javert in Les Misérables (1862). Instead, he elevated downtrodden, anti-royalist Frenchmen like those who incited the French Revolution.

In setting Hugo’s text, Saint-Saëns demonstrated that he shared these anti-Catholic and anti-royalist beliefs of Post-French Revolution Romantics, but Saint-Saëns also had a deep academic interest in the ancient world. He published essays about the Roman lyre and theatrical traditions based on studies of ancient Roman art. Saint-Saëns believed in the importance of large performing forces in spacious venues.2

La lyre et la harpe consists of a prelude and twelve movements. Saint-Saëns conducted the first performance in Birmingham in August 1879, leading a group of 500 musicians. Saint-Saëns’s setting of Hugo’s poem elaborates on the core idea that Greco-Roman and Christian philosophies can coexist as they did in France in his time. The work is orchestrated for SATB choir, SATB soloists, and full orchestra. Through careful use of key areas, thematic material, and textures Saint-Saëns unites the movements symmetrically with No. 7, which combines Harp and Lyre text, as the center point of the work. The Prelude, No. 7, and the Epilogue’s joining of musical and poetic material from the two characters clearly shows Hugo’s idea that the Lyre and Harp philosophies can coexist.

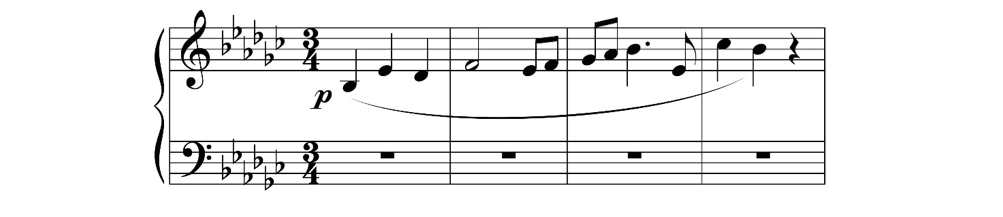

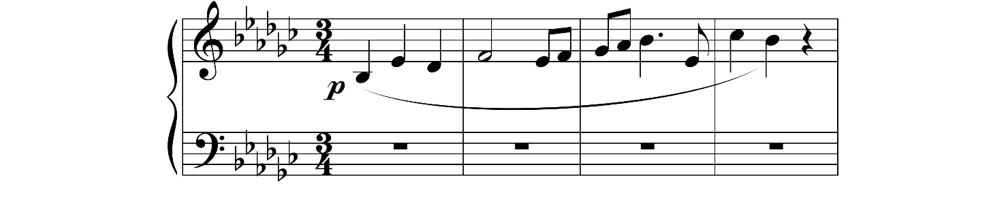

Saint-Saëns consistently contrasts the Lyre and Harp movements using textural differences. The ABAB form Prelude sets up the textural dichotomy, switching from solo organ in the Harp sections to thicker orchestral texture in the Lyre sections. The Harp movements use a sparse orchestral texture. The Harp theme that opens the Prelude (Example 1) is played quietly on solo organ, perhaps harkening to the style of Catholic church organists. Most movements from the Harp’s perspective are sung without the choir. Only one, No. 6, includes choir, but it is in support of a tenor soloist.

Example 1: Prelude, La lyre et la harpe, Organ, mm. 1-4, “Harp theme”

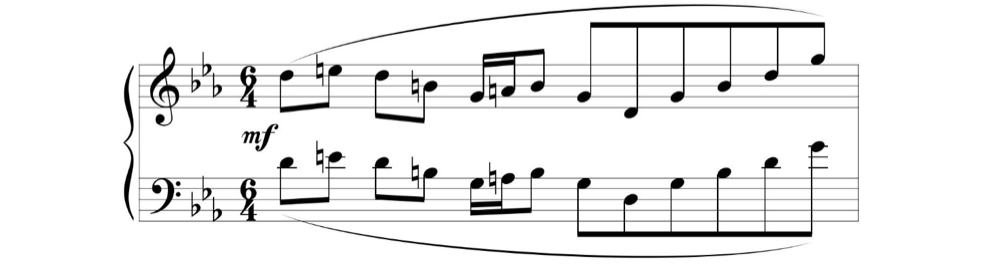

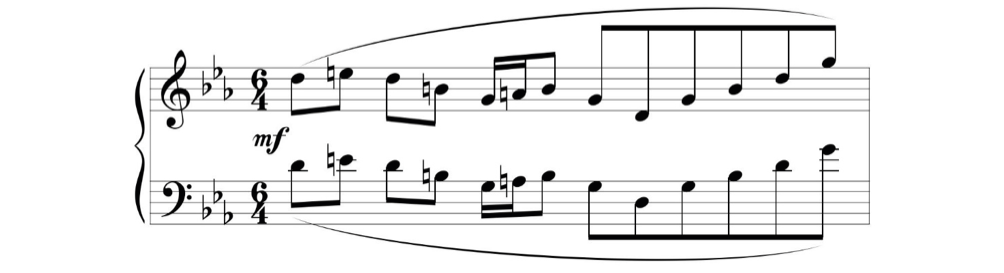

The Lyre theme (Example 2) appears in the harps because they are the closest orchestral instrument to the ancient lyre in timbre. Saint-Saëns makes a textural contrast between the Harp and Lyre sections by involving the choir in all but two of the Lyre movements. This use of choir coupled with consistent full orchestra could reference the composer’s impression that Greco-Roman theatre included large choruses and attracted large audiences.

Example 2: No. 1, La lyre et la harpe, Harp, m. 60, “Lyre theme”

Example 2: No. 1, La lyre et la harpe, Harp, m. 60, “Lyre theme”

Saint-Saëns creates symmetry between the key areas of each of the movements in La lyre et la harpe. The orchestral Prelude begins in E-flat minor and both Part 1 and Part 2 end in E-flat major. In the first part, the keys descend from E-flat in thirds to C minor in No. 4, to A major in No. 5, then back to E-flat major in No. 6. The key areas of the second part seem to depart from those in the first. There are three key areas in No. 7, the first movement of the second part. An ambiguous C minor, the relative minor of E-flat major, goes to A-flat major and then D major. From there, Saint-Saëns moves key areas in thirds, ascending from F-sharp major (No. 8) to A major (No. 9) to C major (No. 10), landing on G minor in the penultimate movement before ending in E-flat major in the Epilogue. Saint-Saëns further reinforces the relationship between the beginning and end of the piece by quoting the Prelude, No. 1, and other movements in the Epilogue.

Although Saint-Saëns’s La lyre et la harpe may have not had lasting success, it may have helped other French composers who successfully referenced ancient musical styles, such as Satie’s comical Gymnopedies or Debussy’s Syrinx. These brief works for soloists are overall more evocative and approachable than the large philosophical questions Saint-Saëns delved into in La lyre et la harpe. Nevertheless, it is because of this philosophical nature that La lyre et la harpe can benefit from close study. While not frequently heard today, La lyre et la harpe reflects important aspects of French Romanticism and the continued interest in Greco-Roman musical styles.

Patricia Rose McKown Schuelke, Dana Point, California, 2020

1 Roger Magraw, “Religion and Anti-Clericalism,” in France, 1800-1914: A Social History (New York: Routledge, 2002), 158-194.

2 Timothy Flynn, “The Classical Reverberations in the Music and Life of Camille Saint-Saëns,” Music in Art 40, nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall 2015): 255-266.

For performance material please contact Durand, Paris.

Camille Saint-Saëns

(geb. Paris, 9. Oktober 1835 - gest. Algier, 16. Dezember 1921)

La lyre et la harpe

Kantate für Orchester, SATB-Chor und SATB-Solisten, op. 57 (1879)

Vorwort

Camille Saint-Saëns ist heute vor allem für sein bezauberndes Orchesterwerk Le carnaval des animaux und die melodramatische Oper Samson et Dalila bekannt. Obwohl die Themen dieser beiden Werke sehr unterschiedlich sind - das erste stellt allseits bekannte Tiere innerhalb eines musikalischen Programms dar, während das zweite eine berühmte biblische Geschichte erzählt -, sind beide einem westlichen Publikum zugänglich und vertraut, was sicherlich zur anhaltenden Popularität der Stücke beigetragen hat.

Ein weniger bekanntes Werk von Saint-Saëns jedoch ist ein besserer Einstieg in die kreative Welt des Komponisten. Seine dreizehnsätzige Kantate La lyre et la harpe konzentriert sich auf einige der zentralen Ideen der französischen Romantik: Glaube, Liebe, Tod und die Aufgabe des Künstlers in der Welt. Sie basiert auf dem gleichnamigen Gedicht von Victor Hugo aus dem Jahr 1822 und ist das erste Auftragswerk eines französischen Komponisten für das Birmingham-Festival, was die Bedeutung von Saint-Saëns in der damaligen Musikwelt verdeutlicht.

In Hugos Gedicht wetteifern die Lyra (die das griechisch-römische Heidentum repräsentiert) und die Harfe (die für das Christentum steht) miteinander und versuchen, einen Dichter davon zu überzeugen, ihrer jeweiligen Weltanschauung zu folgen - am Ende entscheidet der Dichter, dass beide Konzepte in der Kunst verwendet werden können. Im 19. Jahrhundert lebten Heidentum und Katholizismus in Frankreich miteinander, hatte doch das wachsende wissenschaftliche und künstlerische Interesse an Griechenland und Rom auch den Dialog über die nicht-katholischen Traditionen der Verehrung Gottes angeregt.1 Hugos Werke kritisierten die herrschenden Klassen, einschließlich der Monarchie und der katholischen Führer, wie etwa in den berühmten Schurkereien des Claude Frollo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) und Inspektor Javerts in Les Misérables (1862). Gleichzeitig priesen sie unterdrückte, antiroyalistische Franzosen wie jene, die zur Französischen Revolution aufriefen.

Mit der Vertonung von Hugos Text zeigte Saint-Saëns, dass er die Überzeugungen der Romantiker teilte, die nach der französischen Revolution Kirche und Monarchie ablehnten, aber er hegte auch ein tiefes akademisches Interesse an der Antike und veröffentlichte als Ergebnis seiner Studien der antiken römischen Kunst Essays über die römische Lyra und alte Theatertraditionen. Saint-Saëns war von der Bedeutung von Massenszenen in überdimensioniertem Ambiente überzeugt.2

La lyre et la harpe besteht aus einem Präludium und zwölf Sätzen. Saint-Saëns dirigierte die erste Aufführung des Werks in Birmingham im August 1879 mit 500 Musikern. Die Vertonung des Gedichts von Hugo nimmt sich des zentralen Gedankens an, dass wie zu seiner Zeit griechisch-römische und christliche Philosophien nebeneinander existieren können. Das Werk ist für SATB-Chor, SATB-Solisten und grosses Orchester gesetzt. Durch die sorgfältige Verwendung von Tonarten, thematischem Material und Texturen gruppiert Saint-Saëns die einzelnen Abschnitte um Satz 7, der den Text von Harfe und Lyra verbindet und den Mittelpunkt des Werkes darstellt. Präludium, Satz Nr. 7 und der Epilog, in denen das musikalische und poetische Material der konkurrierenden Richtungen zusammengeführt wird, verwirklichen deutlich Hugos Idee, dass die Philosophie von Lyra und Harfe durchaus miteinander leben können.

Saint-Saëns konfrontiert die jeweiligen Sätze der Lyra und der Harfe mit Hilfe von Unterschieden in der Struktur. Das Präludium in der ABAB-Form konstituiert die strukturelle Zweiteilung, indem es von der Solo-Orgel in den Harfenteilen zu einer dichteren Orchesterstruktur in den Lyrateilen wechselt. Die Harfen-Sätze verwenden eine sparsamere orchestrale Textur. Das Harfen-Thema, das das Präludium eröffnet (Beispiel 1), erklingt leise auf der Solo-Orgel, vielleicht dem Stil der katholischen Kirchenorganisten abgelauscht. Die meisten Harfensätze verzichten auf Chorgesang. Nur einer, Nr. 6, enthält einen Chor, der aber von einem Tenorsolisten unterstützt wird.

Beispiel 1: Präludium, La lyre et la harpe, Orgel, mm. 1-4, „Harfen-Thema“

Beispiel 1: Präludium, La lyre et la harpe, Orgel, mm. 1-4, „Harfen-Thema“

Das Lyra-Thema (Beispiel 2) erscheint in den Harfen, denn sie kommen der antiken Lyra in der Klangfarbe am nächsten. Saint-Saëns stellt einen strukturellen Kontrast zwischen den Harfen- und Lyra-Sektionen her, indem der Chor mit Ausnahme von zwei Sätzen an allen Lyra-Sätzen beteiligt ist. Diese Verwendung von Chor und einem durchgängig grossen Orchester könnte auf den Eindruck des Komponisten verweisen, dass im griechisch-römischen Theater große Chöre eingesetzt wurden, die ein großes Publikum anzogen.

Beispiel 2: Nr. 1, La lyre et la harpe, Harfe, T. 60, „Lyra-Thema“.

Saint-Saëns schafft eine Symmetrie zwischen den Tonartbereichen der einzelnen Sätze in La lyre et la harpe. Das orchestrale Präludium beginnt in es-Moll, Teil 1 und Teil 2 enden in Es-Dur. Im ersten Teil fallen die Tonarten von Es in Terzen nach c-Moll in Nr. 4, nach A-Dur in Nr. 5 und schliesslich geht es wieder zurück nach Es-Dur in Nr. 6. Die Tonarten des zweiten Teils scheinen von denen des ersten Teils abzuweichen. Es gibt drei Tonartbereiche in Nr. 7, dem ersten Satz des zweiten Teils. Ein zweideutiges c-Moll, das parallele Moll von Es-Dur, geht erst nach As-Dur, dann D-Dur. Von dort bewegt Saint-Saëns die Tonarten in Terzen, sie steigen von Fis-Dur (Nr. 8) über A-Dur (Nr. 9) nach C-Dur (Nr. 10) auf, landen im vorletzten Satz in g-Moll und enden im Epilog in Es-Dur. Saint-Saëns verstärkt die Beziehung zwischen Anfang und Ende des Stückes noch weiter, indem er das Präludium, Nr. 1 und andere Sätze des Epilogs zitiert.

Auch wenn Saint-Saëns‘ La lyre et la harpe keinen dauerhaften Erfolg verzeichnen konnte, mag das Werk doch andere französische Komponisten inspiriert haben, die sich wie Satie in seinen komischen Gymnopedien oder Debussy in Syrinx gekonnt auf alte Musikstile bezogen. Diese kurzen Werke für Solisten sind insgesamt evokativer und zugänglicher als die großen philosophischen Fragen, die Saint-Saëns in La lyre et la harpe vertieft hat. Dennoch kann La lyre et la harpe gerade wegen dieser philosophischen Natur von einer genauen Untersuchung profitieren. Auch wenn das Werk heute nicht mehr häufig zu hören ist, spiegelt es doch wichtige Aspekte der französischen Romantik und das anhaltende Interesse an griechisch-römischen Musikstilen wider.

Patricia Rose McKown Schuelke, Dana Point, Kalifornien, 2020

1 Roger Magraw, „Religion und Anti-Klerikalismus“, in Frankreich, 1800-1914: Eine Sozialgeschichte (New York: Routledge, 2002), 158-194.

2 Timothy Flynn, „Der klassische Nachhall in der Musik und im Leben von Camille Saint-Saëns“, Musik in Art 40, Nr. 1-2 (Frühjahr/Herbst 2015): 255-266.

Aufführungsmaterial ist von Durand, Paris, zu beziehen.