Schule der Frauen (In two volumes with German libretto)

Liebermann, Rolf

74,00 €

Preface

Rolf Liebermann

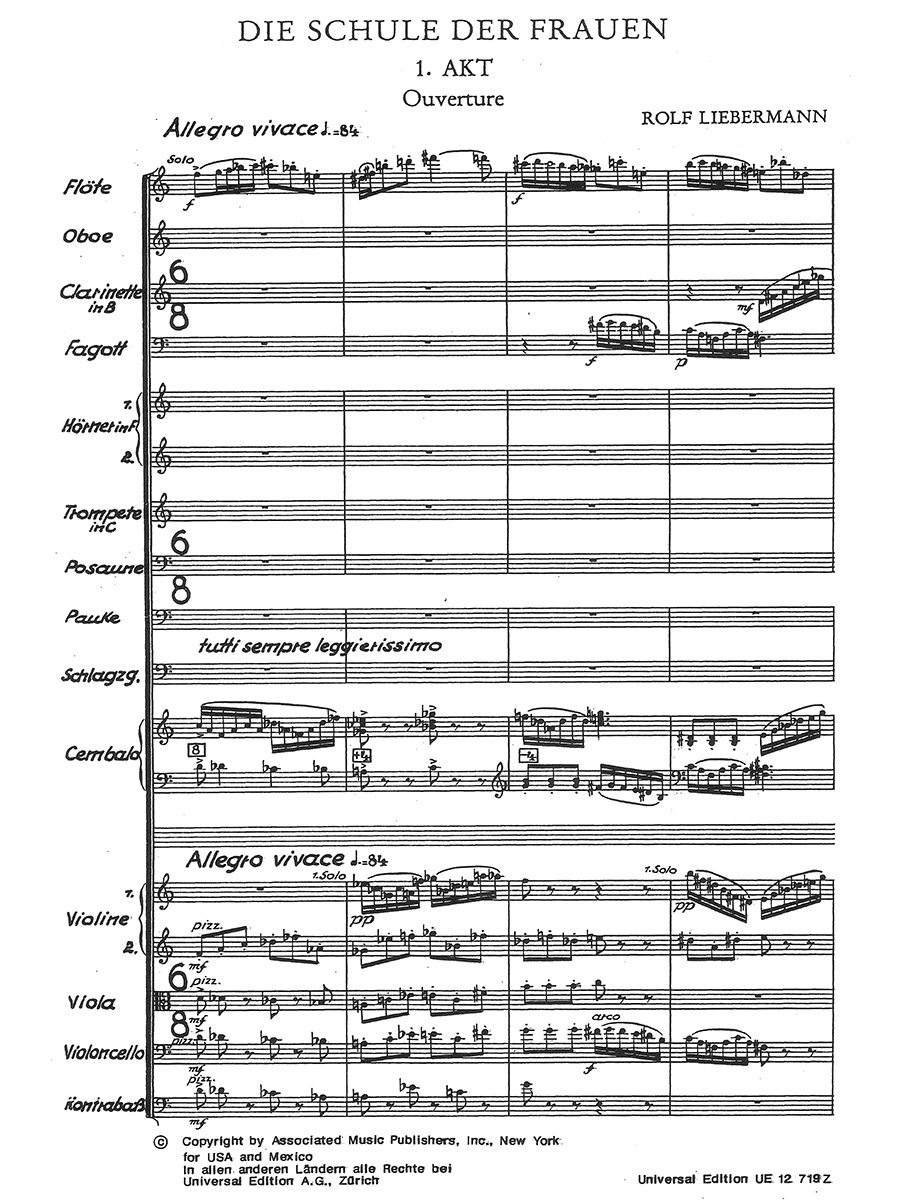

Die Schule der Frauen

(The School for Wives)

Opera buffa in three acts after Molière

(b. Zurich, 14 September 1910 – d. Zurich, 2 January 1999)

Preface

“Why did I stop composing? I ask myself the same question today, and there is doubtless something incomplete and contradictory in my answer: I am, as already mentioned, of the opinion that one cannot do several things at once. On the day that I began to compose, I laid down the conductor’s baton, and from the day that I went into musical administration, I never wrote another note. […] On the example of Thomas Mann, who wrote for three hours every day, not one hour more or less, I composed from 2:00 pm to 7:00 pm every day. In this way, from 1945 to 1955 I partook of a turbulent period of contemporary music history with the regularity of a metronome.”1

Thus, with undue modesty, Rolf Liebermann described his retirement from contemporary composition and the advent of his career as an opera administrator – a career that made him a seminal figure in the world of European opera, whether in Hamburg (1959-73 and 1985-88), where he gave no fewer than twenty-three world premières, or at the Paris Opéra (1973-80), where he commissioned Saint François d’Assise from Messiaen (1983), arranged for the completion of Berg’s Lulu (1979), and produced one of the most beautiful of all opera films, Joseph Losey’s Don Giovanni (also 1979). Yet even if the above quote is not exactly true (great composers can indeed combine multiple careers, as witness Mahler, and Liebermann continued to compose well after 1955, if no longer with metronomic regularity), there is something surprising, almost Rossini-esque, about his voluntary retirement from the front rank of German opera composers to the sidelines of musical administration. The three operas from his main period of creativity – the politically scandalous Leonore 40/45 (1952), the jazz-drenched Penelope (1954), and the effervescent Schule der Frauen (1955, rev. 1957) – were among the most highly esteemed and frequently performed works of their day, placing him alongside Hans Werner Henze, Wolfgang Fortner, Boris Blacher, Giselher Klebe, and Gottfried von Einem as a leading figure of German-language opera. How he might have developed thereafter if he had continued to devote himself whole-heartedly to composition is anyone’s guess.

Die Schule der Frauen began life as a one-act English-language opera entitled The School for Wives, commissioned for the remarkably active if unlikely hub of contemporary music in Louisville, Kentucky. The commission, which caught Liebermann completely by surprise (“All I had known of Louisville until then was that horses were bred there”), was arranged by an influential arts patron and early founder of the Kentucky Opera: “His name was Moritz von Bomhard, a German-American who, thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation, had the necessary funds to order operas from practically every well-known composer for the entire decade. The contract contained two important clauses: the libretto had to be in English, and the work must not be more than fifty-five minutes in length – this limit being prescribed by the duration of a Columbia LP.

Liebermann was pleased to accept the offer and turned once again to his librettist Heinrich Strobel, who had written the librettos to Leonore 40/45 and Penelope. This time the plan, much like Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s Ariadne auf Naxos of 1912, was to lend a modernist veneer to a classical play by Molière (the splendid L’École des femmes of 1662) by counterpointing the original plot with a contemporary score and alienating theatrical devices: “In Die Schule der Frauen, we tried to combine baroque style with a contemporary handwriting. I therefore employed the harpsichord in the bitonal score like a set of ironic quotation marks, and Strobel in turn “alienated” the comedy by introducing a Molière who, almost like a Pirandello figure, watches how the young people deal with his play [and who] gradually slips into each of the other male characters, one of whom is always absent at any given moment (another Strobel idea).

The one-act English version, with a translation provided by Lady Elisabeth Montagu (“a living descendent,” Liebermann proudly notes in his memoirs, “of the Montecchi from Romeo and Juliet”), was duly premièred at a concertante performance in Louisville on 3 December 1955. The opera’s unanimous success in these provincial backwaters encouraged the authors to attempt a performance at the New York City Center Opera the following year. Expectations were high: “Following the great success of our short opera in Louisville in 1955, we were so confident of victory after the New York première that we celebrated until five o’clock the next morning awaiting the morning papers, where, so we thought, the critics would laud us to the skies. And what did we read upon opening the New York Herald Tribune? The critic, “after hearing our opera, had enjoyed listening to the dulcet strains of a typewriter”! The other reviews were of a similar bent. Fortunately Die Schule der Frauen was already firmly scheduled on the program of the 1957 Salzburg Festival.”

Read more > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Opera Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Opera |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 494 |