Le Buisson ardent (The Burning Bush), Poème symphonique op. 203 & 171

Koechlin, Charles

38,00 €

Preface

Charles Koechlin – Le Buisson ardent [The Burning Bush]. Poème symphonique op. 203 & 171

(b. Paris, 27 November 1867 – d. Rayol-Canadel-sur-Mer, Département Var, 31 December 1950)

(1945 & 1938)

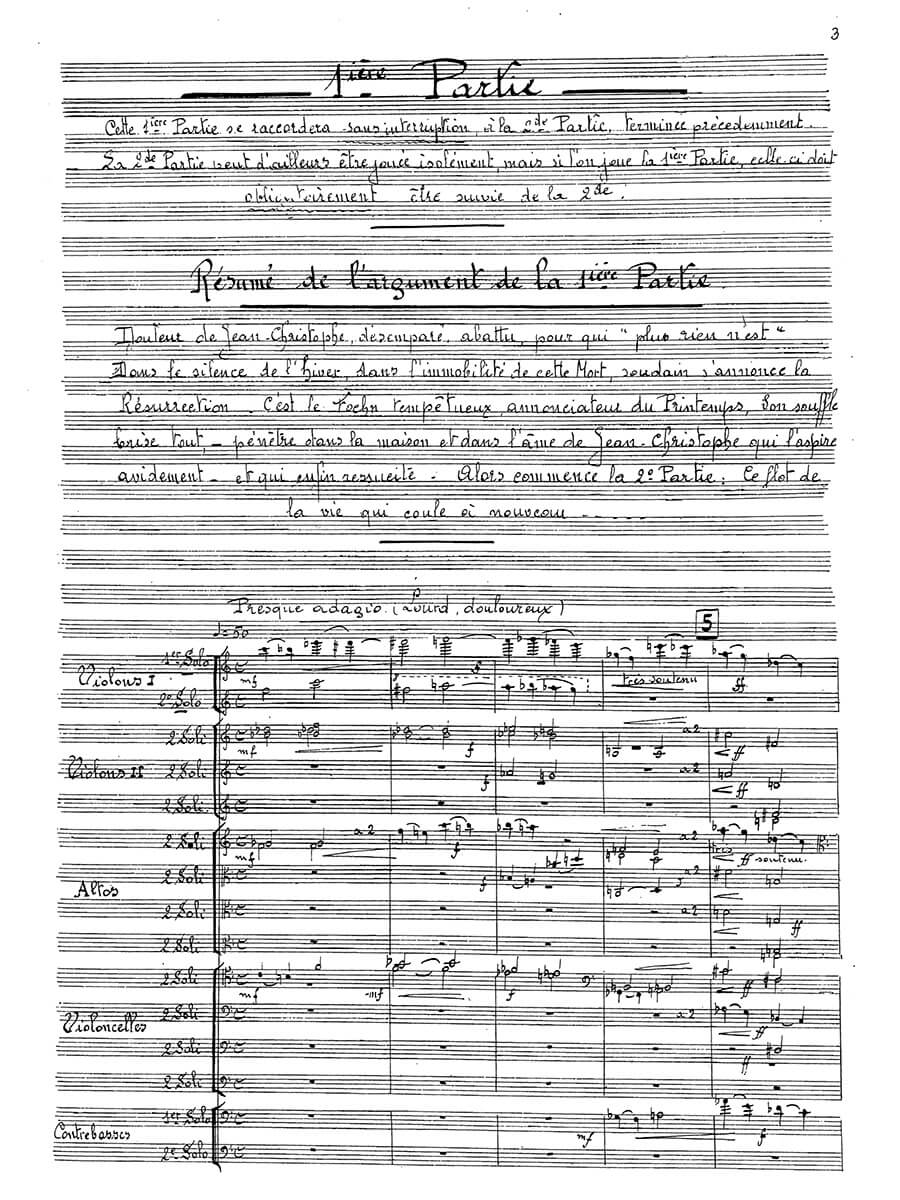

I Prèsque adagio, lourd, douloureux (p. 3) – Allegro, non troppo (p. 8) – Andante moderato (p. 10) – Mouvement de l’Allegro (p. 11) – Très animé (p. 44) – Allegro moderato (p. 45) – Animé (p. 49) –

Un peu plus large (p. 59)

II Molto moderato (p. 69) – Très calme (p. 70) – Très tranquille (p. 86) –

Laissez le mouvement s’animer (p. 89) – Double plus lent (p. 91) – Fugue. Allegro vivo (p. 107) –

Très calme (p. 138) – Plus large (p. 149) – Très doux, extrèmement calme (p. 154) –

Très tranquille (p. 155)

Preface

“The life of the artist who thinks about beauty above all else is enviable. It allows to move towards an ideal. Such a life gives freedom. This freedom is: ‘to be entirely yourself,’ to write in your ivory tower, which can become a beacon for the world.” (Charles Koechlin)

They all thought highly of him, whether Debussy, Dukas, Roussel, Ravel, Migot, Milhaud, Honegger, Rivier or Poulenc. Darius Milhaud, for example, who was 25 years younger and by no means backward-looking, wrote that he had “the impression of dealing with the music of a magician who might belong to the generation after me.” But attempts to popularize Koechlin’s works did not meet with resounding success. Charles Louis Eugène Koechlin (pronounced Kéklin) was born the seventh child of a wealthy, educated Alsatian family. He wanted to become an astronomer – echoes of this inclination may be the many evocative night pieces and moods in his works. At the age of fifteen he began to compose, and in 1890 he finally decided on the musical path. But both strands of talent – the free artist and the systematic researcher – continued to coexist, becoming increasingly indissolubly intertwined throughout his long life. At the Paris Conservatoire he studied with André Gedalge and Jules Massenet, then with Gabriel Fauré, whose assistant he was from 1898 to 1901. More than any other role model, Fauré, who not only entrusted him with the orchestration of his “Pelleas et Melisande” suite, became an aesthetic example for him in his discreetly progressive, never obtrusive diction. Not only Fauré, but also Debussy trusted Koechlin’s magical orchestration skills, and the fusion between composer and orchestrator in “Khamma” is perfect. At the beginning of his creative period (1890-1908), an extensive lied production dominates. The first orchestral pieces are impressionistic mood paintings. After 1908, according to his own statement, Koechlin gradually began to perfect his “technique du développement” and to escape from conventional guidelines. He found his style, which in its intricate diversity eludes restrictive definition, and from then on not only finally entered what he considered the most delicate terrain with chamber music, but above all designed his large, overflowing imaginative tone poems for large orchestra. If one marvels at his gigantic, multifaceted œuvre (he still composed half a year before his death on New Year’s Eve 1950), one gets the impression of a multiple laboratory in which several works were created as work-in-progress projects over many years in parallel, overlapping ways, referring back and forth to one another. The resulting quality is very versatile. Koechlin was primarily not a completer, but an inventor. He knew the orchestra, its combinatory and characteristic phenomena like hardly anyone else (except perhaps Gustav Mahler, Alban Berg or later Jean-Louis Florentz), whereby Koechlin admittedly opened up new sound constellations in a much more targeted manner than any of his predecessors or contemporaries and chiseled them out with highly sensitive skill in his bold formal designs. He was an alchemist of orchestral sound, whereby his inexhaustible imagination went hand in hand with methodical comprehension, as his comprehensive “Traité de l’orchestration” in 4 volumes attests. No study has penetrated deeper into the secrets of orchestral treatment. And if there were patent rights on instrumental combinations, Koechlin would be the uncatchable record holder – whereby his combinations, contrary to many others, always work, as can be seen in the never tiring coloring and registration of the pure monody in “La loi de la jungle”, in the bizarre intellectual satire in monkey garb of “Bandar-Log”, in the unlimited color dimensions of “La course de printemps”, the “Seven Stars Symphony”, “Le Buisson ardent” or “Le Docteur Fabricius”. All of this is music for experienced gourmets, which in its generally static, energetically non-stringent manner reveals its beauties only with repeated listening, except perhaps for works such as the “Seven Stars Symphony”, which tableauized great film stars such as Lilian Harvey, Greta Garbo or Charlie Chaplin in an outrageously fascinating manner. Apart from opera, Koechlin tackled all genres, even the mass (without credo!). His musical cosmos is inexhaustible. The paths he follows lead into the unpredictable. …

Read full preface / Das ganze Vorwort lesen > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 162 |

| Size | 225 x 320 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |