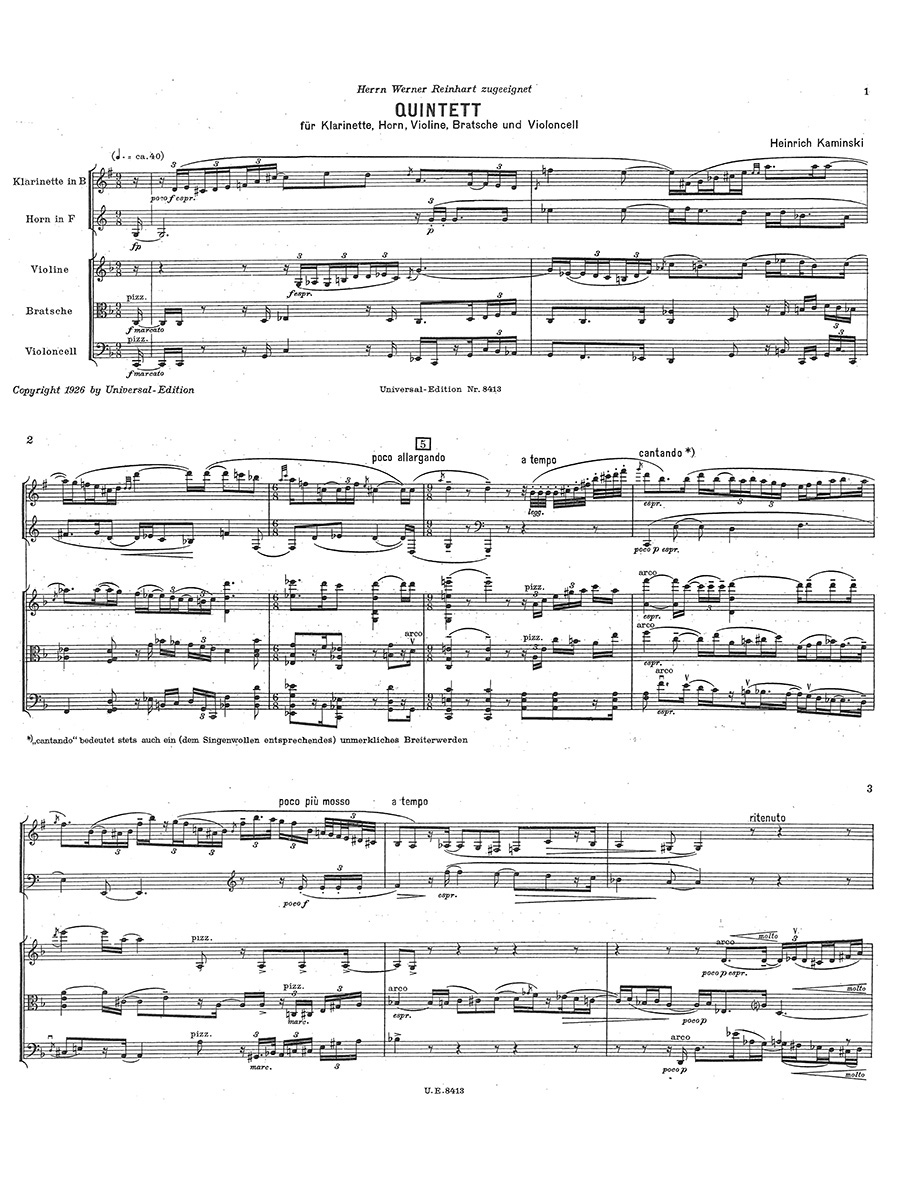

Quintet for clarinet, horn, violin, viola and cello (small size landscape format)

Kaminski, Heinrich

25,00 €

Preface

Heinrich Kaminski

(b. Tiengen, 4 July 1886 — d. Ried near Benediktbeuern, 21 June 1946)

Quintet (1923-24) for clarinet, horn, violin, viola and cello

I Lento rubato (p. 1) – en Angelus (bretonisches Volkslied). Adagio (p. 24) –

Allegro (p. 32) – Ruhig (p. 38) – Subito allegro (p. 43) – Andante (p. 53) – Allegro (p. 54) – Grazioso (p. 55) – Tempo primo (p. 59)

Preface

In the turbulent years of transition from the post-romantic tonal tradition to so-called modernism, Heinrich Kaminski was one of the few composers who managed to maintain continuity despite the change of paradigms, and to fashion a distinctive, wholly unmistakable and timeless style that neither echoes nor denies nor obstructs the past. His artistic motto was “Evolution, not Revolution,” and his clear intention was to transport the supreme achievements of German counterpoint, from Johann Sebastian Bach and late Beethoven to the symphonic grandeur of Anton Bruckner, into new realms of expression and intercultural cohesion. In this he succeeded convincingly and with flawless craftsmanship. He also succeeded in conveying essential aspects of his artistic bearing and ethos to his most gifted and earnest pupils, particularly Reinhard Schwarz-Schilling (1904-1985) and Heinz Schubert (1908-1945). From the mid-1920s to the early 1930s he was considered a central voice in contemporary music, a figure standing above reaction and avant-garde alike. Yet his art was condemned to insignificance by the Third Reich. This is hardly surprising for a man who saw in Bismarck the “primary source of the dogged, headstrong, and unfortunately all-too successful resistance to the honest and admirably perspicacious efforts of Crown Prince Friedrich III (in conjunction with his spouse and his sister, the Grand Duchess, and his brother-in-law, the Grand Duke of Baden) to create a genuine federation of German lands (without Prussian hegemony!), so that beginning in 1871 the Prussianization of Germany was able to proceed ever more viciously along its path to this catastrophic end.” Though Kaminski’s music escaped being blacklisted, it was considered undesirable and no longer performed, with few exceptions (especially Heinz Schubert in Flensburg and Rostock). With the cessation of hostilities his day might well have come, but he only had one more year to live, and it is highly unlikely that the crypto-fascist spirit of total serialism, that bane of modern music, would have granted him a sufficiently large niche in which to operate. As his music is also extremely complex and very difficult to perform, there has yet to be a Kaminski renaissance, although some leading musicians, such as Lavard Skou Larsen in Neuss, have taken up his cause with passion and expertise. His major creations belong to the genres of sacred music (with orientalizing tinges), orchestral music, and chamber music. Nor should we forget his two basically untheatrical stage works, Jürg Jenatsch and Das Spiel vom König Aphelius, whose mystic ambience brooks comparison with Wagner’s Parsifal, Enescu’s Œdipe, and Szymanowski’s Krol Roger. Kaminski’s work gave rise to a mighty and multi-layered current violently cut short by the vicissitudes of German history. Perhaps it is possible today to draw on that current and to rise above the contradictions of history.

Kaminski’s chamber music, though smaller in quantity than his sacred music and less spectacular than his orchestral music, nevertheless forms a major part of his œuvre and covers his entire creative lifetime. His first fully valid pieces of chamber music, likewise published by Universal Edition, were the Quartet in A minor for piano, clarinet, viola and cello (1912) and the String Quartet in F major (1913). They were followed by the mighty String Quintet in F-sharp minor with its great final fugue, a work that he published in a new arrangement in 1927 and allowed his pupil Reinhard Schwarz-(Schilling) to arrange under his supervision as “Work for String Orchestra” in 1928. Both were published by Universal Edition, as were his Canzona for violin and organ (1917) and the Three Sacred Songs for soprano, violin and clarinet to his own words (1923). In 1924 there followed the present Quintet for clarinet, horn and string trio, and in 1929 the Prelude and Fugue in A minor for violin and organ (both published by Universal Edition). Then he again turned to the string quartet with Prelude and Fugue on the Name ABEGG (Litolff, 1931), followed in 1932 by Music for Two Violins and Harpsichord (Peters) and in 1934 by Canon for Violin and Organ (Universal Edition) and Prelude and Fugue for Solo Viola (Peters). In 1935 Peters published the three-volume Klavierbuch and the Ten Short Exercises for Contrapuntal Piano Playing (his complete published piano works, presumably composed over a longer period of time). His final three chamber works were issued by Bärenreiter, the principal publisher of his later years: Music for Cello and Piano (1938), the ambitious if unfortunately titled Hauskonzert for violin and piano (1941), and the Ballad for horn and piano (1943)… (Christoph Schlüren, Translation: Bradford Robinson) …

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Chamber Music |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 88 |

| Special Size | 280 x 160 mm (landscape format) |