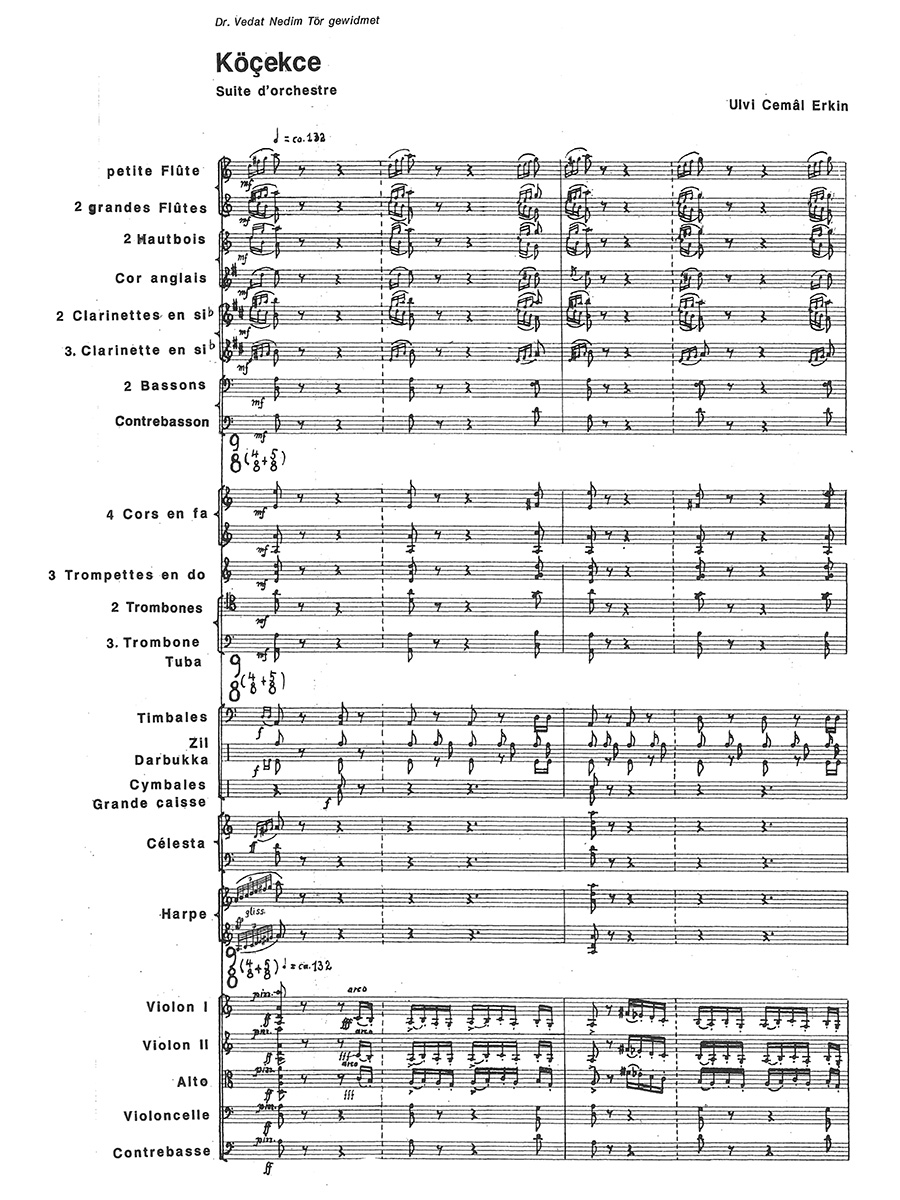

Köçekçe (Köçekçeler), Dance rhapsody for orchestra (first time available for sale)

Erkin, Ulvi Cemal

25,00 €

Preface

Ulvi Cemâl Erkin

(b. Istanbul, 14 March 1906 – d. Ankara, 15 September 1972)

Köçekçe (Köçekçeler)

Dance rhapsody for orchestra (1942)

The Variety and History of Turkish Music

Turkish music presents us with a picture of extreme diversity. This, of course, is closely connected with the history of this country, its ethnic composition, and the vast differences between its urban and rural cultures. If we attempt to find a common denominator for these features, we notice (notwithstanding some notable exceptions) an attitude marked on the one hand by pride and dignity, and on the other by tenderness, grace, and sentimental yearning. The Turkish peoples are of nomadic descent, warlike, and accustomed to harsh conditions, much like the Seljuks from the Kazakh steppes, who converted to Islam toward the end of the tenth century under their eponymous leader, Prince Seljuk. They went on to subdue large parts of Persia in the eleventh century, established themselves in Baghdad as a protecting power, and, in 1071, defeated the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert under Alp Arslan, launching the Turkish settlement of Anatolia. In the eleventh century, proceeding from their capital city of Konya, they founded the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate. Their rulership gave way to the Ottoman Turks at the beginning of the fourteenth century, but the national identity of present-day Turks is rooted in the flowering of the medieval Seljuk Empire. As deep as the Arabic influence may have been on their life style, not to mention the European influence beginning in the nineteenth century, the Turks (much like the Persians) have always preserved their defining characteristics in all outward manifestations.

But what do we mean by “Turkish”? The towering symbolic figure and mightiest saint, invoked by all Turks to the present day, was Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī or, more simply, Rumi. He was born in 1207 in Balkh (Khorosan in present-day Afghanistan), where his father, Baha al-Din Walad, was a Sufi master. When the Mongols under Genghis Khan fell upon Balkh in 1219, the family fled via Mecca to Anatolia. While en route, the young Rumi met the great aged Sufi master Farīd ud-Dīn Attār. The Seljuk sultan offered his father a professorship at the University of Konya, which Rumi himself took over some time around 1230. Rumi’s encounter with the holy man Shams-i-Täbrīzī is one of the most moving stories of transformation in world literature. Today Rumi is known throughout the world not only as one of the most magnificent poets in history, but as the founder of the Mevlevi community, which, after his death, was reorganized into a Sufi order, with the seat of the Whirling Dervishes established in Konya. In the days of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1923), the Sufi communities were hugely important and intimately connected with the ruling dynasties. After Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) had succeeded in warding off Turkey’s defeat in the First World War and had retaken Izmir in 1923, the Ottoman Europe officially came to an end, and Atatürk proclaimed the Turkish Republic on 29 October 1923. Beginning in 1928 he erected a secular state with a strong military arm as a source of stability – a constellation that has existed to the present day. He also banned all activities of the Sufis, who nevertheless continued to be held in highest esteem by the population.

Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī, whom the Turks call simply Mevlânâ (“our master”), died in Konya in 1273. Though he wrote all his works in Persian, the Turks consider him one of their own, alongside Hājī Baktāsh Walī (1209-71, the founder of the Bektashi Order), Yunus Emre (1240-1321), and Nasreddin Hodja (1208-84, the “Till Eulenspiegel of the Orient”). Turkish identity, in other words, is a mixture: Turkish in living interaction with Persian, Arabic, and later Western influences, not to mention a sizable admixture of Armenian, Kurdish, Greek, and other minorities. If the rulers had truly assimilated the Sufi spirit, these ethnic differences would not have become such a powder keg, and Turkey would not have become yet another exponent of that fateful nationalism that drew the entire world ineluctably into the abyss at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Anyone who sets out to explore the origins of Sufism and encounters the patent similarities in Sanskrit, the writings of Zoroastrianism, Zen Buddhism, and Toltek shamanism, will understand the truth of this statement.

My place is the Placeless,

My trace is the Traceless;

‚Tis neither body nor soul,

For I belong to the soul of the Beloved.

I have put duality away,

I have seen that the two worlds are one;

One I seek, One I know,

One I see, One I call.

He is the first, He is the last,

He is the outward, He is the inward;

I know none other except ‚Ya Hu‘ and ‚Ya man Hu.‘

The two worlds have passed out of my ken.

From Rumi’s Divan of Shams-i-Täbrizi

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 90 |