Seven pieces for Small Orchestra

Dvorák, Antonín

26,00 €

Preface

Dvorák, Antonín

Seven pieces for Small Orchestra

(Sedm Skladeb pro maly Orchestr)

Preface

Antonin Dvořák was born in 1841 in the Czech Lands, which were then part of the Austrian Empire. He became one of the most famous composers among the non-German minority groups during the age of political nationalism in Europe. His musical works included orchestral and chamber music, songs, keyboard works, choral music and operas.

His best-known orchestral music included symphonies, overtures, symphonic poems and concertos. However, he also wrote works for chamber orchestra which included suites, serenades and dances, which are little known in the concert hall even today. In 1867 he composed seven works for chamber orchestra, the Sedm Skladeb pro maly Orchestr [Sieben Stucke für kleines Orchester]. The British musicologist John Clapham refers to these pieces as “Intermezzi.”

These works were not “student” pieces. Among the other compositions Dvořák composed in this period were his first two symphonies (both dating from 1865), several chamber works, and Cyprise, a cycle of songs, some of which he subsequently recomposed for string quartet. It is important to note that these works were written while the composer was earning his living as a violist in Prague. The publishers with whom he dealt were in no way so well known as those he met a decade later through the good offices of Johannes Brahms, who became aware of Dvořák’s work in 1877, when the younger composer submitted several of his scores for a competition in Vienna for which Brahms was among the judges.

In these works, he was influenced by occasional pieces of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. His familiarity with music of Brahms, Johann Strauss the Younger, Anton Bruckner and other contemporaries was still in the future when he composed the seven pieces.

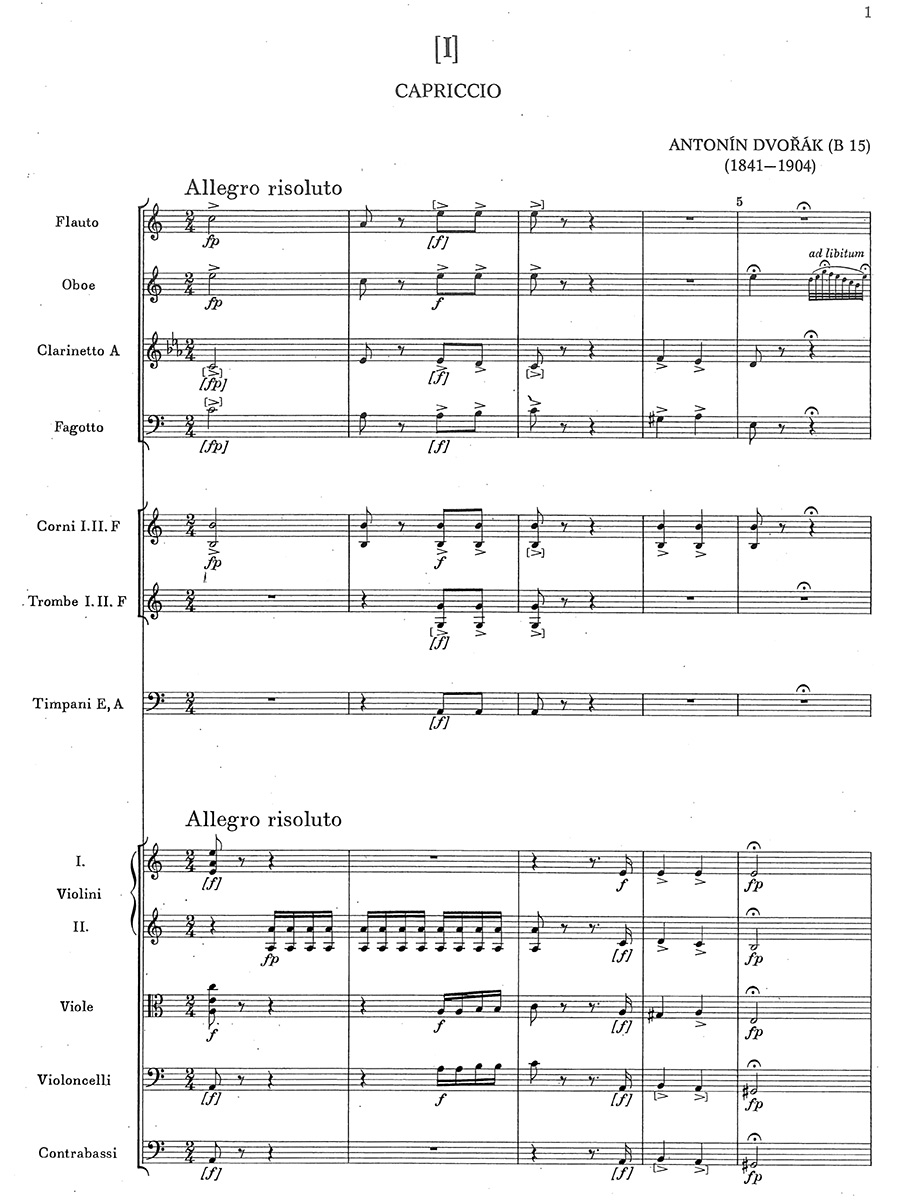

The orchestration of the pieces is uniform throughout: single flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani and five-sectioned strings. They were not published in the composer’s lifetime. The only edition to date is in the Dvořák Critical Edition, Series III, volume 24, (Works for Chamber Orchestra), which was published by Supraphon (Prague) in 1989, edited by Jiri Berkovec.

The content and style of these pieces shows considerable variety. However, the inter-movement tonal balance is conservative.

1. Capricco [allegro risoluto] in a minor (2/4 meter)

2. Legni [andante sostenuto] in a minor (3/4 meter)

3 Interlude [con molta espressione] in A major (3/4 meter)

4. Interlude [allegro con brio] in A major (6/8 meter)

5. Allegro assai in D major (cut-time)

6. Serenata [andantino con moto] in D major (6/8 meter)

7. Interlude [allegro animato] in d minor (cut-time)

Although Dvořák was earning his living in a theatre orchestra in Prague, speculation about the possibility that these pieces might have been intended for use as incidental music in the theatre after they were discovered in 1951 has been considered and ruled out, which was noted by Jiri Berkovec in the edition of 1989. While Dvořák, unlike Brahms, did become involved with music for the stage (in some cases having been influenced by Wagner’s operatic style), he appears to have been more successful with his symphonic works as an expression of Czech nationalism, which was an important priority in his life both professionally and personally. The orchestral works like his Seven Pieces, the two Serenades, the Czech Suite and even such works as the Prague Waltzes (all of which date from the mid- to late 1870s) are considered to be extensions of his symphonic style.

The Berlin publisher Simrock, who released many of Brahms’s works, accepted Dvořák on the recommendation of Brahms, but that did not prevent disagreements during their long relationship. Even Dvořák’s orchestration of the Hungarian Dances no. 17-23 of Brahms appears to have originated with Simrock rather than either of the two composers.

The extensive research covering the music of Dvořák accords much more attention to large-scale works than intimate ones like these pieces. The best sources of information with which to initiate new contributions and discoveries, apart from the Critical Edition of 1989, are listed below:

– Clapham, John. Antonin Dvořák: Musician and Craftsman. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1966.

– Burghauser, Jarmil. Antonin Dvořák: Thematiky Katalog, Bibliografie, Prehled, Zivota a Dila. Praha: Artia, 1960, 2nd edition 1996.

Other publications which predate the first descriptions of the Sedm Skladeb can be studied for historical context of Dvořák research. The most active scholar in the field early in the twentieth century was Otakar Sourek (see below):

– Sourek, Otakar. Dvořáks Werke, Chronologisches, thematisches und systematisches Verzeichnis

Berlin: Simrock, 1917. Zivot a dilo Antonina Dvořáka. Praha: Hudebni Matice Umelecke Besecy, 1916-1933.

4 vols.

German version: Antonin Dvořák, sein Leben und sein Werk. With Paul Stefan. Wien: Dr. Rolf Passer, 1935.

English version. Dvořák: Life and Work. Translated by Yandray Wilson Vance.

New York: Greystone Press, 1941.

Professor Sourek’s book published by Simrock in 1917 is worth comparing with the research of Burghauser, which was published nearly half a century later and benefitted from many new discoveries which necessitated the Critical Edition. On the other hand, Sourek’s four-volume book of 1916-1933 – although published in Czech and not easily available to scholars – is probably worth a serious search compared to the German and English versions, which must have been grossly abridged for the benefit of non-Czech readers.

Susan M. Filler, Chicago, Illinois, October 2016

For performance material please contact Bärenreiter, Kassel. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 96 |