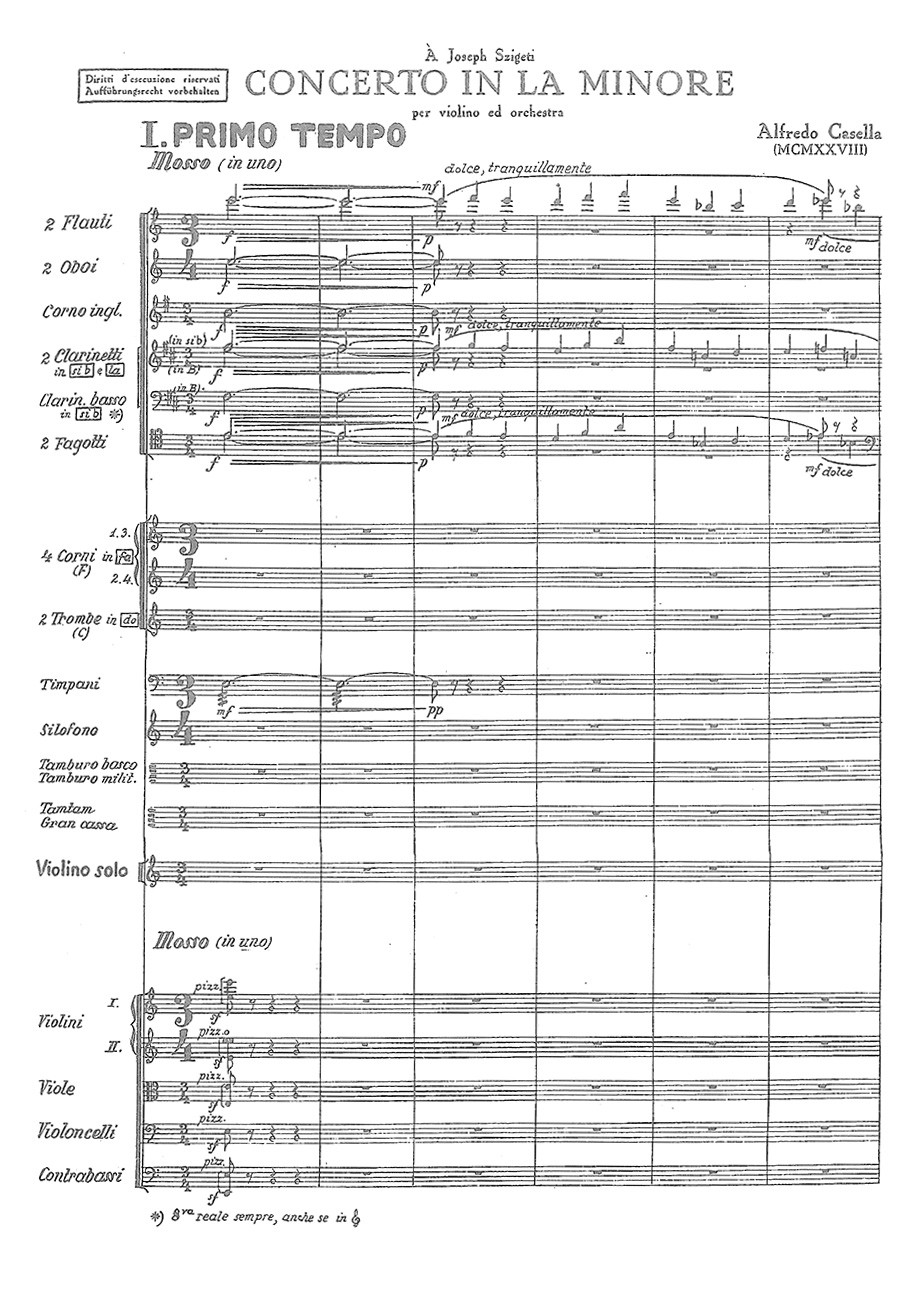

Violin Concerto in a minor Op. 48

Casella, Alfredo

31,00 €

Preface

Alfredo Casella – Concerto in A Minor for violin and orchestra, Op. 48 (1928)

(born Turin, 25 July 1883 – died Rome, 5 March 1947)

I Mosso – Grave, quasi funebre – Allegro molto vivace – Tranquillamente – Allegro animato – Animando sempre – Grave, pesante – Cadenza – Grave, funebre – Tempo del principio / (attacca:) p. 1

II Adagio – Tempo del Rondò – Come prima – Cadenza / (attacca:) p. 49

III Rondò. Allegro molto vivace e scherzoso p. 92

Preface

After Alfredo Casella had put behind him his periods of impressionism, expressionism and new objectivity, his stylistic development from the end of the 1920s shows a clear tendency to merge neo-Classical and Romantic elements into an archaic and unambiguously tonal idiom, which also integrates the most recent achievements. Composed after the neo-Baroque Partita for piano and orchestra, the Divertimento Scarlattiana for piano and small orchestra and the neo-modal Concerto romano for organ and orchestra, the Violin Concerto is the most neo-Romantic among his larger-scale compositions.

Casella wrote the Concerto for the great Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti (1892–1973). He started to work on the composition on 13 February 1928, in Rome, and finished it on 2 July 1928, in Boston, where he had his second season (of three) as conductor of the Boston Pops (the popular concerts of the Boston Symphony Orchestra). He introduced the Bostonians to much new music, but in the end was unable to win them over for himself. The Violin Concerto was premiered by Szigeti on 8 October 1928, in Moscow, accompanied by Persymphans, the Moscow orchestra which played without a conductor on principle. The publication Musikblätter des Anbruch (Vienna, 1928, Vol. 8) comments: ‚The work scored a brilliant success. The premiere performance of an Italian composer by a Hungarian artist in Moscow is noteworthy‘.

In his autobiography With Strings Attached (2nd edition, New York, 1967), Szigeti recalls the workshop atmosphere during the Persymphans rehearsals which, since everyone was allowed a say in artistic matters, engaged all the musicians in a manner that was motivated, serious and showed exceptional mutual respect: “I rehearsed and played with my back turned to the orchestra, of course, the strings grouped in semicircle around me, the half-dozen or so immediately to my right and left having their backs turned to the audience, and the wood winds and brass behind me, vertically across the inner part of the semicircle […].. We even gave a world première: that of Casella‘s concerto, dedicated to me; the composer, conscious of the unusualness of this première, had all the data pertaining to it engraved on the flyleaf of the score.”

Incidentally, Nicolas Slonimsky refers to Persymphans in his Lectionary of Music (New York, 1989) under the entry ‚Conducting‘: “An interesting experiment was made in Russia after the revolution to dispense with a conductor as an undemocratic vestige of musical imperialism. Indeed, a conductorless orchestra of Moscow lasted for ten seasons until it was abandoned as a perverse distortion of socialism, and the conductors returned to the Soviet podium to exercise their authoritarian power over the downtrodden musical masses. Even the most vocal skeptics about the role of conductors agree, however, that a musical coordinator is necessary to lead the highly complex orchestral scores of modern works.”

Casella‘s Violin Concerto soon saw further performances in London, Paris and Frankfurt, and another famous violinist added it to his repertoire, this time with a conductor, as reported by Musikblätter des Anbruch (Vienna, 1929, Vols. 7–8): “Alfredo Casella‘s new Violin Concerto has just been performed in Boston by Louis W. Krasner and the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the composer‘s baton. Joseph Szigeti, too, will […] soon perform it in Vienna with the composer conducting.”

After its initial success, the work has fallen into near-complete oblivion. Only one really excellent (and equally prominent) performance has been captured in a live recording: Ida Haendel‘s in Torino in 1969, accompanied by the Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI under Sergiu Celibidache.

Translation: Ernst Lumpe & Martin Anderson

For performance materials please contact the original publisher, Universal Edition, Vienna (www.universaledition.com).

Reprint in this form by kind permission of the original publisher, Universal Edition AG, Vienna, 2002.

Read preface / Vorwort > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Violin & Orchestra |

| Pages | 168 |

| Size | 160 x 240 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |