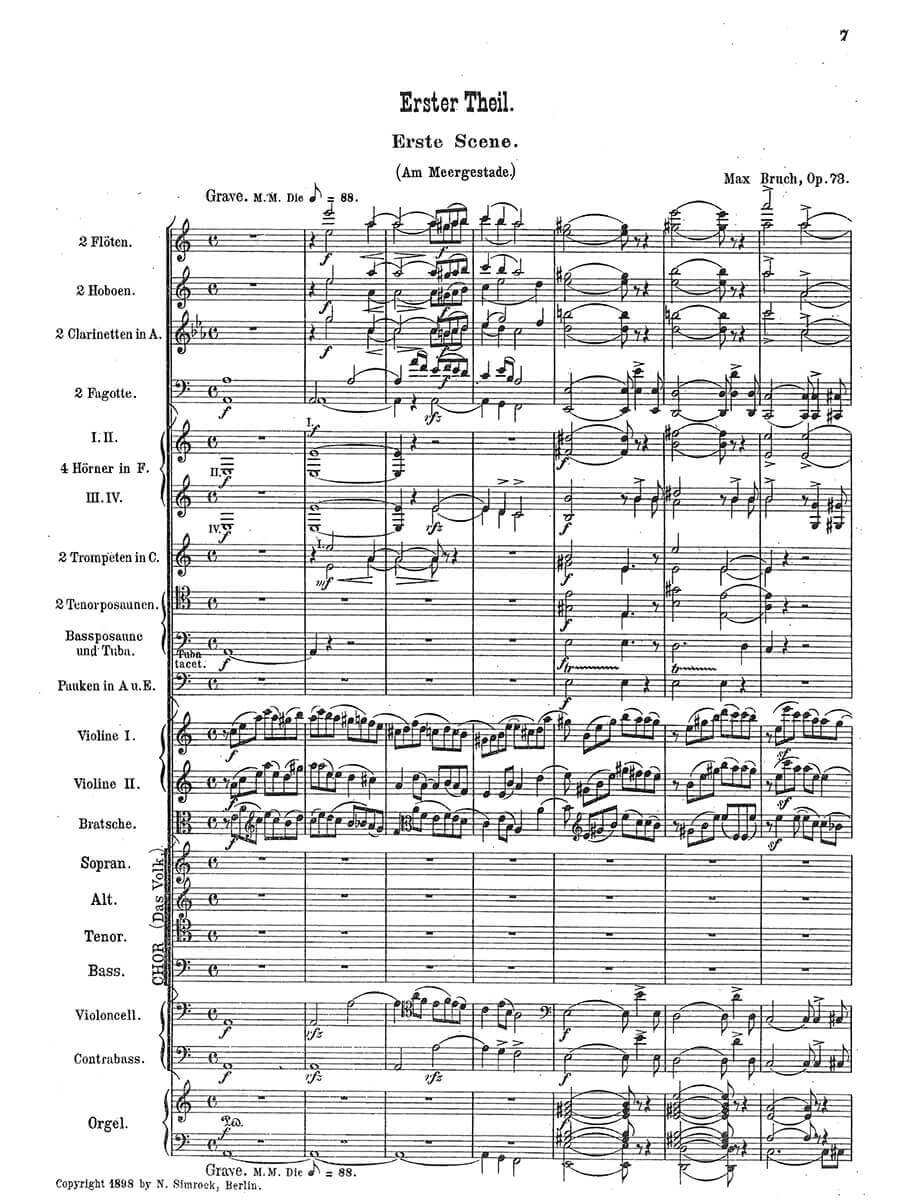

Gustav Adolf Op.73, Oratorio for Chorus, Solo Voices, Orchestra and Organ

Bruch, Max

65,00 €

Preface

Max Bruch

Gustav Adolf, op. 73

(b. Jan. 6, 1838, in Cologne; d. Oct. 2, 1920, in Friedenau near Berlin)

Oratorio for Chorus, Solo Voices, Orchestra and Organ

Text by Albert Hackenberg

Preface

Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26, is so well known that it is easy for us today to overlook the fact that the composer was also deeply committed to vocal music. One can go further: he understood vocal music to be the foundation of the whole of his compositional activity. Even his instrumental music, in particular his wonderful works for violin and orchestra, were defined for Bruch by the idea of song. When speaking to the music journalist Arthur Abell, Bruch – himself a trained pianist, moreover – observed in this context, “the reason is that the violin can sing a melody better than the piano, and melody is the soul of music”.1 His preference for vocal music can be seen early in his life. This, for example, is what the 20-year-old composer wrote to his teacher and mentor in Cologne, Ferdinand Hiller, on the occasion of a period of study in Leipzig:

“At the moment, however, the emphasis and the glory of musical life here lies only in instrumental music. Much less is done for singing than is the case with us in the Rhineland. There seems to me to be a dearth of proper delight in singing as well as of resonant voices. This is bad news for me since, as you know best of all, it is above all vocal music that I wanted to perform.”2

By comparison with the instrumental music, which makes up only about a third of his total output,3 vocal music forms a considerably larger proportion of Bruch’s oeuvre, and there is no doubt that the wonderful oratorios represent the very best of his vocal writing. With the exception of Moses, op. 67, which is based on biblical material, they all treat mythological and historical subjects, so that Bruch can be said to have made a significant contribution to an increasingly dominant trend within the genre, namely the secular oratorio.4 It is true that, following “[Joseph] Haydn’s Seasons, largely secular material had been consistently present in the oratorio since 1801”, but an intensification of this tendency in the sense of a “turn to the secular oratorio” can only be discerned after the middle of the century.5 With his secular oratorios Odysseus, op. 41 (UA 1873), Arminius, op. 43 (UA 1875), Achilleus, op. 50 (UA 1885), and also Gustav Adolf, op. 73 (UA 1898),6 printed here, Max Bruch thus played a decisive role in the further development of the genre.

More than any other genre, the oratorio was for Bruch influenced by political and historical events, as can be seen particularly in the cases of the oratorios Arminius and Gustav Adolf. A defining role was in these cases played by the foundation of the Second Empire in 1871 and the developments and conflicts associated with it in the following decades. It is significant that the “process of German cultural nation-formation” only began after the foundation of the Empire and had only a small number of role-models to look back to.7 The commemoration of Germanic heroic figures played an important part in the growth of a German sense of national identity, as is reflected also in the numerous monuments to Germanic heroes erected in the 19th century. Bruch’s oratorio Arminius takes up this trend by having as its subject the victory of the Germans under the leadership of Arminius (Hermann) over the Roman army in the famous Battle of the Teutoburg Forest,8 which is still today commemorated by the monument in the Teutoburg Forest which was dedicated to Hermann in 1875.

A further consequence of the foundation of the Empire was the struggle against Catholicism, which was regarded as an enemy by a protestant Prussia dominant within the German Empire. To this extent it is possible to speak of a “national-protestant orientation in the founding of the Second German Empire”.9 The conflict became increasingly bitter, as can be seen from the comments on the catholic Centre Party made by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck when he almost accused it of high treason.10 On top of this, the Jesuit order, whose activities were prohibited by the Jesuit Law of 1872,11 became a “symbolic battle-cry”.12 Martin Geck has put his finger on the way that the foundation and establishment of the German Empire was coupled with Protestantism: “It is not merely the fact that the Prussian crown is the guarantor of Protestantism, it is rather that the latter is for its part the guarantor of an Empire of the German Nation led by Prussia, whereas in the eyes of Protestantism a Catholicism controlled by the pope or internationally manipulated by the Jesuits represents a threat to the idea of the nation.”13 The energetic opposition to Catholicism that has gone into history under the heading Kulturkampf (“culture struggle”) lasted at least a decade into the 1880s before running out of steam…

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 340 |