Romeo und Julia. Chamber Opera in Three Parts (with German and English libretto)

Blacher, Boris

34,00 €

Preface

Boris Blacher

(b. Newchwang , Manchuria, 19 January 1903 – d. Berlin, 30 January 1975)

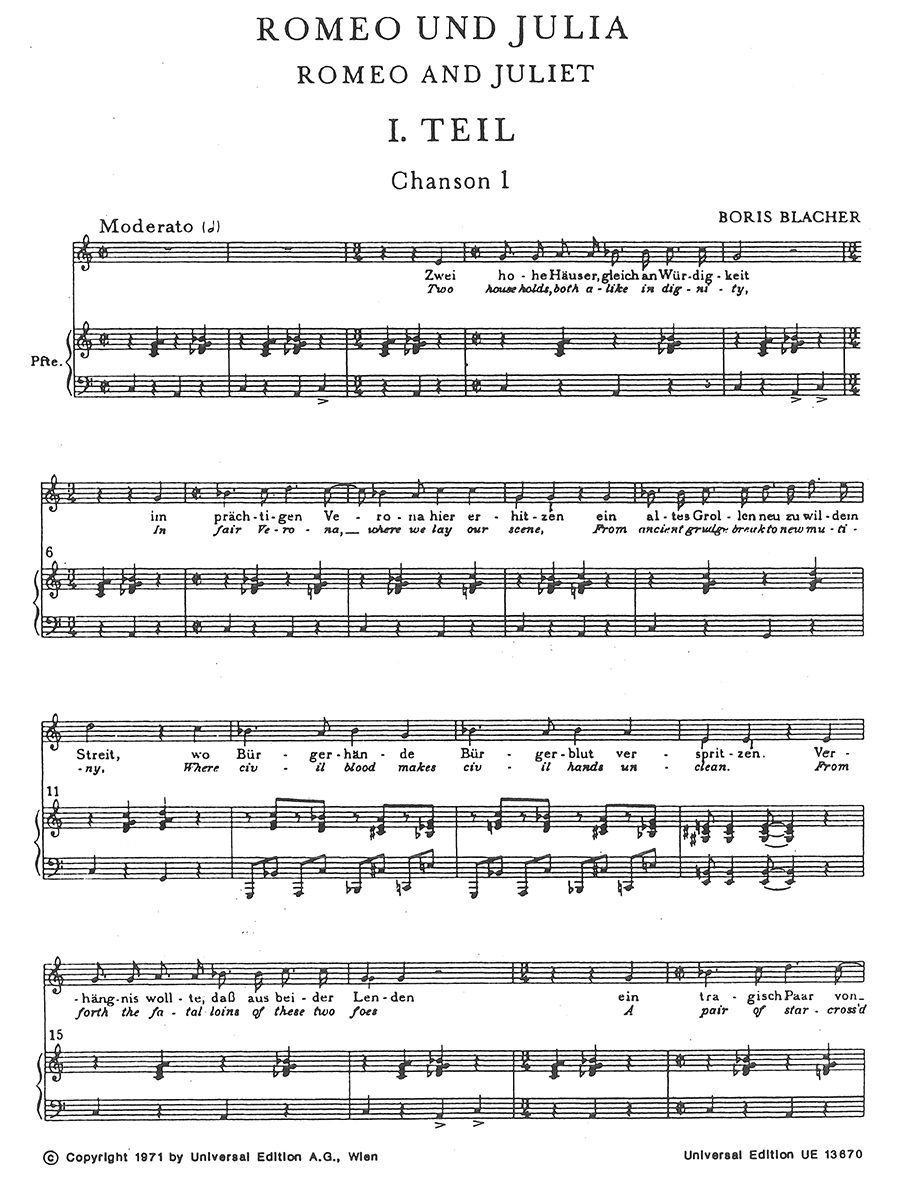

Romeo und Julia (1943-44)

Chamber Opera in Three Parts

after Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

Preface

Of all the major German composers born at the turn of the twentieth century – Weill, Hindemith, Krenek, Hartmann – none can match the colorful biographical background of Boris Blacher. He was born in the Manchurian harbor city of Newchwang (now Yingkou in China), where his father was a distinguished banker of German-Baltic extraction, and spent his entire childhood and adolescence east of the Ural Mountains, whether in Irkutsk, Siberia, or (from 1919) in Harbin in northeastern China. Owing to his family’s rootlessness and the turmoils of early twentieth-century history, his education was conducted variously in English, German, Italian, and Russian, along with a smattering of Chinese dialects. During these years he also picked up lessons in piano, violin, and theory and developed a deep-seated passion for the theater. In Harbin, at the age of sixteen, he made himself indispensable to the local symphony by orchestrating works from piano-vocal scores for the instruments that happened to be at hand. One such work was the whole of Puccini’s Tosca.

By the time Blacher finally set foot in Germany he was already nineteen years old. Accompanied by his mother, he settled in 1922 in Berlin, where he embarked on a study of mathematics and architecture, only to change to music and musicology one year later. When his mother departed for the Baltic in 1925, Blacher, now twenty-two, was left to his own devices, and for years he earned his living in impoverished postwar Berlin as a copyist, musical factotum, and harmonium player in local cinemas. He developed a strong interest in dance, especially as a musical collaborator of the great modernist choreographer Rudolf Laban, and plied his trade as a composer with middling success, composing not only art music but a surprising number of popular songs. His breakthrough finally came in December 1937 when Carl Schuricht performed his Conzertante Musik with the Berlin Philharmonic, and Blacher suddenly found himself proclaimed a celebrity. At the recommendation of Karl Böhm he was appointed head of a composition class at Dresden Conservatory, only to be dismissed a year later for championing such “degenerate” composers as Hindemith and Milhaud (his quarter-Jewish ancestry also argued against him). In the war years, though unemployed, he was among the most frequently performed of Germany’s modern composers. After the war he was instrumental in rebuilding Germany’s musical life from the ashes of the Third Reich, especially at the Berlin Musikhochschule, which he served as professor (from 1948) and director (1953-1970). A fine and much-beloved teacher, speaking Berlin slang with a heavy Russian accent, he taught an entire generation of gifted composers from German-speaking Europe (Gottfried von Einem, Giselher von Klebe, Aribert Reimann, Rudolf Kelterborn, Klaus Huber) and from abroad, whether Korea (Isang Yun), America (George Crumb) or Israel (Noam Sheriff).

As might be expected from this rich background, Blacher’s voluminous musical output is wide-ranging and very diverse, covering every musical genre (except church music), but with a special focus on the theater (fourteen operas, nine ballets, and much incidental music for stage productions and radio plays). Compounding this diversity was his personal philosophy of following each completed piece with one of diametrically opposite character. Nonetheless, his early stage works, from Habemeajaja (1929) to Die Flut (1947), can be slotted into a general style which has acquired the name of “the Weill underground tradition” (David Drew) and follows the “gestic” approach explored in Weill’s collaborations with Bertolt Brecht, especially Der Jasager (1930). In this sense we find Blacher the theater composer in the company of such modernist contemporaries as Paul Dessau, Karl Amadeus Hartmann, and his friend Rudolf Wagner-Régeny.

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Opera Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Opera |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 140 |