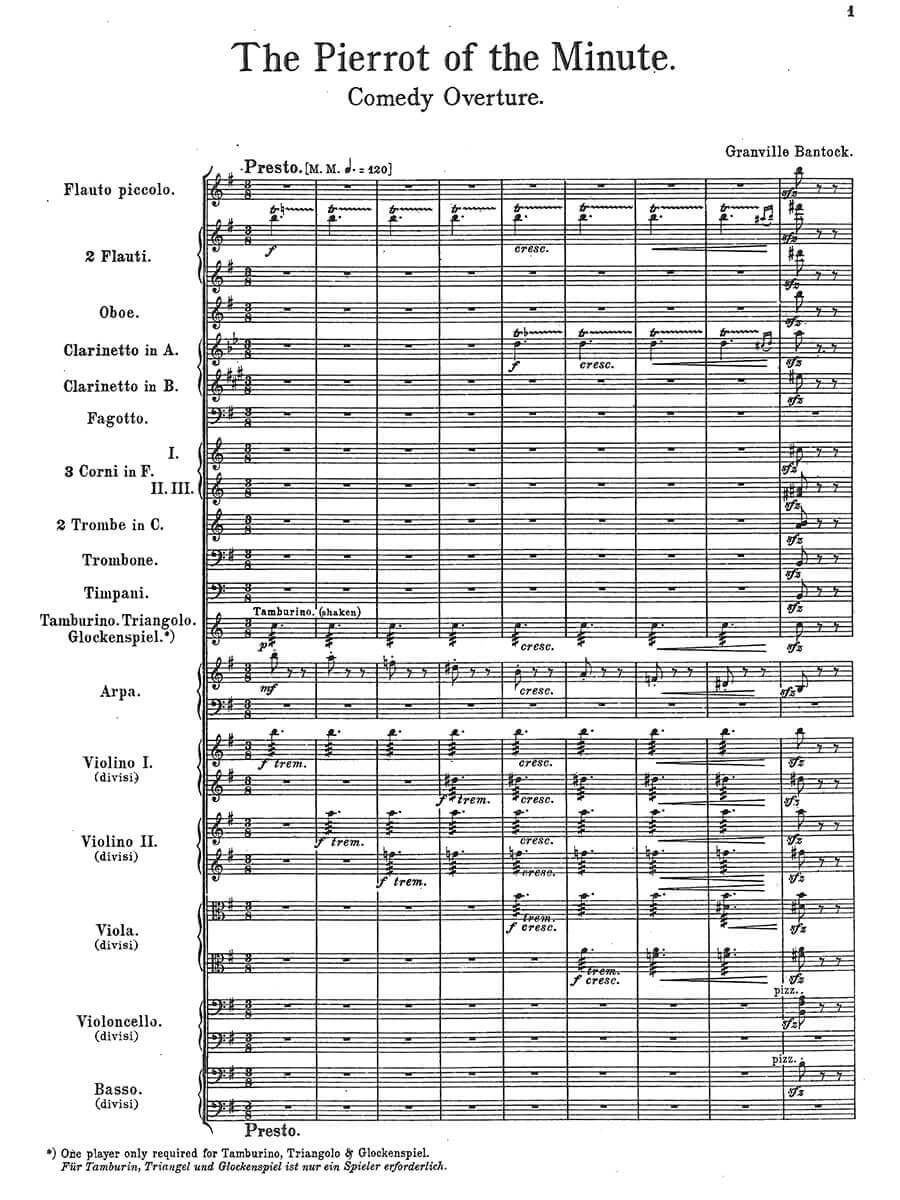

The Pierrot of the minute, A Comedy Overture to a Dramatic Phantasy of Ernest Dowson

Bantock, Granville

29,00 €

Preface

Granville Bantock

(b. London, 7 August 1868 – d. London, 16 October 1946)

The Pierrot of the Minute

(1908)

A Comedy Overture to a Dramatic Phantasy of Ernest Dowson

Preface (by Christopher Little, 2017)

Granville Bantock was a composer caught between two musical cultures. The son of a prominent London surgeon, Bantock studied at the Royal Academy of Music while Tchaikovsky was still a rising star and Wagner rarely appeared on British concert programs. England at the time had conservative musical tastes that preferred Mendelssohn and his English epigone William Sterndale Bennett to the New German School of Wagner, Liszt, and later Richard Strauss. Bantock absorbed techniques from all three of these composers, delighting in the notoriety such “modern” chromatic harmony, dramatic leitmotifs, and colorful orchestration gave him. The fact that Edward Elgar, the first English composer in generations to capture both the public and critical imagination, praised Bantock helped solidify Bantock’s position as a rising figure in English music. In 1900 Bantock succeeded Elgar as the Peyton Professor of Music at the University of Birmingham as well as becoming Principal of the Birmingham and Midland Institute’s school of music. He held both posts for over thirty years. After retiring in 1934 he became Chairman of Trinity College of Music in London, which sent him around the world as an adjudicator at music festivals and competitions. Bantock died in 1946 leaving behind his wife Helen, four children, and hundreds of musical compositions.

During his lifetime Bantock supported many other composers both personally and professionally. Before Bantock moved to Birmingham, he conducted concerts at the New Brighton Tower, a popular resort destination near Liverpool. Though contracted to provide dance music to holiday goers Bantock expanded performances to include concerts of Wagner, Sibelius, Elgar, Hubert Parry, Joseph Holbrooke, and others, often conducted by the composers themselves. Bantock was among the first to popularize the music of Sibelius in England and both he and Elgar traveled to the area to conduct their own works. Later, while maintaining his academic duties in Birmingham, Bantock provided teaching work for several young English composers and helped promote their music. These included Joseph Holbrooke, Rutland Boughton, and Havergal Brian, each a composer as indebted to German Late Romanticism as Bantock himself. Bantock became their personal friend as well as professional supporter through his generosity.

Bantock’s music, considered daring during the early years of the twentieth century, was no longer thought innovatory after the First World War. As the 1920s progressed, British musical tastes turned away from Germanic Romanticism and toward French Neo-Classicism and American popular music. Unaffected, Bantock continued writing as before, producing large-scale symphonies, oratorios, and orchestral works using Wagnerian techniques. By the time serialism became the musical avant garde in the 1930s, Bantock’s Romantic ideals represented a discredited worldview best forgotten. It is only now, after artistic fashions have become less restrictive, that Bantock’s music is being rediscovered as worthy in its own right, dramatic and warm-hearted works of a generous composer.

Bantock was prolific, composing in all genres. Art songs, chamber music, orchestral works, symphonies, oratorios, choral music, and operas flowed from his pen. Besides his use of harmonic, melodic, and instrumental technique derived from German Romanticism, Bantock also favored program music. Each of Bantock’s symphonies and many orchestral works are descriptive, though some are more detailed than others. Bantock was also fascinated by “exotic” cultures ranging from the Middle and Far East to ancient Greece, Celtic Ireland, and historic Scotland. Bantock’s descriptive program music thus often depicted these and other “exotic” cultures or locations in music in genres large and small. The present piece is something of a departure from this “exotic” interest but is nevertheless programmatic. It also demonstrates Bantock’s engagement with a core tenet of Romanticism: unrequited love. Such an engagement lead in this instance to commercial and popular acclaim.

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 225 x 320 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 60 |