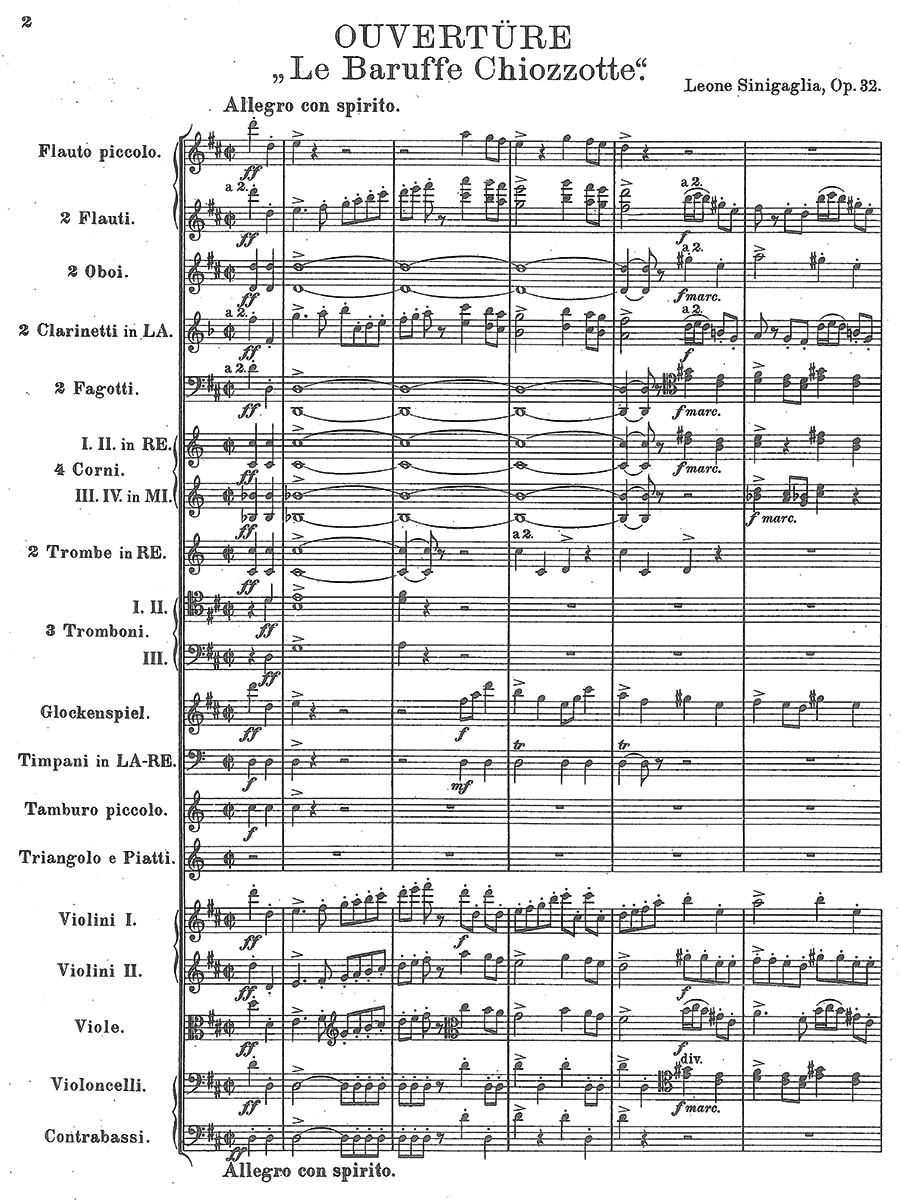

Le Baruffe Chiozzotte (Overture)

Sinigaglia, Leone

19,00 €

Preface

Leone Sinigaglia

(b. Turin, 14 August 1868 – d. Turn, 16 May 1944)

Le Baruffe Chiozzotte

Overture

Preface

Leone Sinigaglia was Jewish. He died in 1944. To read these two facts one after the other is inevitably to assume the worst. Sinigaglia’s place of death, Turin, at least provides reassurance that thoughts of gas chambers and Auschwitz were premature. But that is not to say the composer eluded the »Final Solution«. The seventy-five-year-old was spared deportation only because he collapsed and died of a heart attack as German police were removing him from the Ospedale Mauriziano, in which he and his sister Alina had taken refuge.1 That Sinigaglia should have met such an end seems all the more appalling when one considers the extent to which he had modelled himself as a composer on Austro-German traditions of musical culture. A pupil in Vienna of Brahms’s friend Eusebius Mandyczewski and later of Dvořák, Sinigaglia chose to work, for the most part, in the kinds of genres and forms associated with the more conservative strands of late nineteenth-century Central European composition. From a brief look at his quite slender work-list (less than 50 opus numbers), one might not realize that he was an Italian composer at all. He wrote not a single opera. Sinigaglia’s vocal music consists primarily of Lieder and folksong arrangements; among his chamber music are a string quartet and sonatas for violin and for cello; his orchestral music includes a violin concerto and several works based on popular melodies of his native Piedmont – here the model was Dvořák rather than Brahms.

Sinigaglia’s orchestral music, in particular, enjoyed a good deal of success during his lifetime, both in Italy and abroad. The Overture »Le baruffe chiozzotte« is a case in point. Following its premiere in Utrecht on 21 December 1907 at the hands of the Utrecht Symphony Orchestra under Wouter Hutschenruyter, this music was taken up by many of the leading conductors of the day. The Overture was a favourite of Arturo Toscanini’s, for example, whose radio broadcast of 1947 with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, long available in various bootleg versions, remains the best known performance of the work. Toscanini had first conducted »Le baruffe chiozzotte« almost forty years earlier, at La Scala on 7 May 1908. Sinigaglia’s Overture was in the repertory of other such luminaries as Walter Damrosch, John Barbirolli and Bernardino Molinari. In Britain it was often conducted by Henry Wood, the founder of the Promenade Concerts: the work had been recommended to him by none other than Artur Nikisch. »Nothing gloomy about it«, the latter had said.2 Most remarkably, perhaps, »Le baruffe chiozzotte« was the first item on the very last programme conducted by Gustav Mahler, with the New York Philharmonic, on 21 February 1911. That this music should have entered the international repertory, and been widely and regularly performed right up until the 1940s, will come as no surprise to those who know it. Sinigaglia’s Overture is a gem of early twentieth-century orchestral composition, full of memorable invention and beautifully crafted. The work’s disappearance from concert programmes after the 1950s, even in Italy, is a little mysterious. Tastes change, of course: perhaps after the Second World War comic overtures came to sound all too frivolous. The rediscovery today of this music would be a breath of fresh air for performers and audiences alike.

Le baruffe chiozzotte is the title of one of the best known plays of the eighteenth-century Venetian dramatist Carlo Goldoni, first performed at the Teatro San Luca in Venice on 23 January 1762. Its most celebrated modern production, by Giorgio Strehler at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano in 1962, was filmed for Italian TV in 1966. The title translates, roughly, as Bust-Ups in Chioggia; the play is written in the dialect of Chioggia itself, a small town at the southern end of the Venetian lagoon. There is no attempt on Sinigaglia’s part to follow the plot outline of Goldoni’s comedy in his score. Indeed, it is difficult to see how that would be possible, given the complexity of the relationships between the characters and their rapid developments. A series of increasingly furious and even physically violent exchanges (the baruffe of the title) develops following the flirtation of the boatman Toffolo with Lucietta, who is engaged to the fisherman Titta-Nane, though everything is resolved in the end, through the intervention of the legal functionary Isidoro. Nor would it seem quite right to suggest (in the usual cliché) that Sinigaglia captures the »spirit« of Goldoni’s play, much beyond a general jollity of tone. The elevated style of his music is far removed from the popular speech of the play’s cast of fishwives and fishermen, their daughters and daughters’ fiancés. On the other hand, a kind of parallel between Goldoni’s drama and Sinigaglia’s Overture may conceivably be traced in terms of the latter’s form. Just as the characters of Le baruffe chiozzotte find themselves, in their rage, acting against their own interests and desires (especially the leading couple, Lucietta and Titta-Nane), so the sonata structure Sinigaglia appears clearly to have established in the work’s opening stages becomes thoroughly confused, blown off course, as it were, in the course of its development. Only at the very end are the threads drawn together and formal clarity regained.

It would be unfair to suggest that Sinigaglia’s music has nothing popular or eighteenth-century about it. The subordinate theme, first heard at

Development begins immediately, at the Un poco più mosso eight bars before [4]. And it is here that Sinigaglia comes closest to Goldoni, creating what amounts to a species of musical baruffa. At the same time, the composer demonstrates his Austro-German ethos, ceaselessly moulding his material into new thematic shapes. To start with, a pair of phrases, the second beginning at [4], brings attention alternately to the anapaestic rhythms of the subordinate theme and its more lyrical side. An extension of the second phrase leads into a passage in continuous quavers (eight bars before [5]), which in turn brings a new idea, at the Allegro moderato at [5]. There is no stability to the B minor briefly affirmed here, Sinigaglia building to a further new idea with the Allegro at [6]. And again the music continues to grow in excitement, always in bustling – or perhaps squabbling – continuous quavers. An especially boisterous tutti, five bars before [7], precedes the climactic arrival of a point of clear harmonic focus one bar before [8]. Dominant preparation in A is sustained from here all the way to the Moderatamente mosso at [9], where the subordinate theme appears in that key, the music having in the meantime calmed down considerably.

At last, then, this theme has been stated in the correct key. But by now it is no longer the correct key. For this is presumably the recapitulation of Sinigaglia’s sonata, a recapitulation in which the themes appear in reverse order, with the second in what is in fact the wrong key, since it ought to be the tonic. At [10], Sinigaglia moves to E major and begins a passage of secondary development. Especially noteworthy is the lyrical expansion (over a long-held dominant pedal) nine bars before [11]: yet another new idea, and a very Straussian one. Straussian too is the sudden harmonic shift to the dominant of D flat major at the Più mosso nine bars after [11]. It is only at the Più animato one bar before [12] that the music returns to sharp regions. What sounds like a dominant preparation in G leads unexpectedly, at the Allegro at [13], to a return to the music of [5]. Here this material is directed towards a dominant pedal in D (the Animato ten bars before [14]), which ushers in the return of the principal theme in the tonic, con brio (at [14]). Now the overall form of the Overture appears clearer. After the first exuberant and then expansive directions in which Sinigaglia’s two development sections take the music of his subordinate theme, the principal theme returns to round off the structure. A good deal of the recapitulation of the principal theme is literal, enhanced orchestral brilliance aside. Only towards the end of the middle section of the theme’s ternary form (from the fifth bar of [16]) does Sinigaglia begin to institute substantial changes, initially to bolster the final return of the opening idea, at [17]. This final statement is considerably modified: there is no modulation to the dominant (compare bars 4–6 of [17] with bars 4–6 of [2]), and the music moves swiftly to a coda in a blazing D major.

Benjamin Earle, 2016

1 One of the earliest published accounts of the deaths of Sinigaglia and his sister is to be found in D.P.L. [Luigi Dallapiccola], »Leone ed Alina«, Corriere di Firenze, 15/16 October 1944, p. 3. See also Luigi Rognoni, »Leone Sinigaglia«, in Adelmo Damerini and Gino Roncaglia (eds.), Musicisti piemontesi e liguri, Siena, Ticci, 1959, p. 64.

2 See Henry Wood, My Life of Music, London, Gollancz, 1938, p. 271.

For performance material please contact Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Score No. | 1796 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Special Edition | |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Performance materials | |

| Piano reduction | |

| Specifics | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 56 |