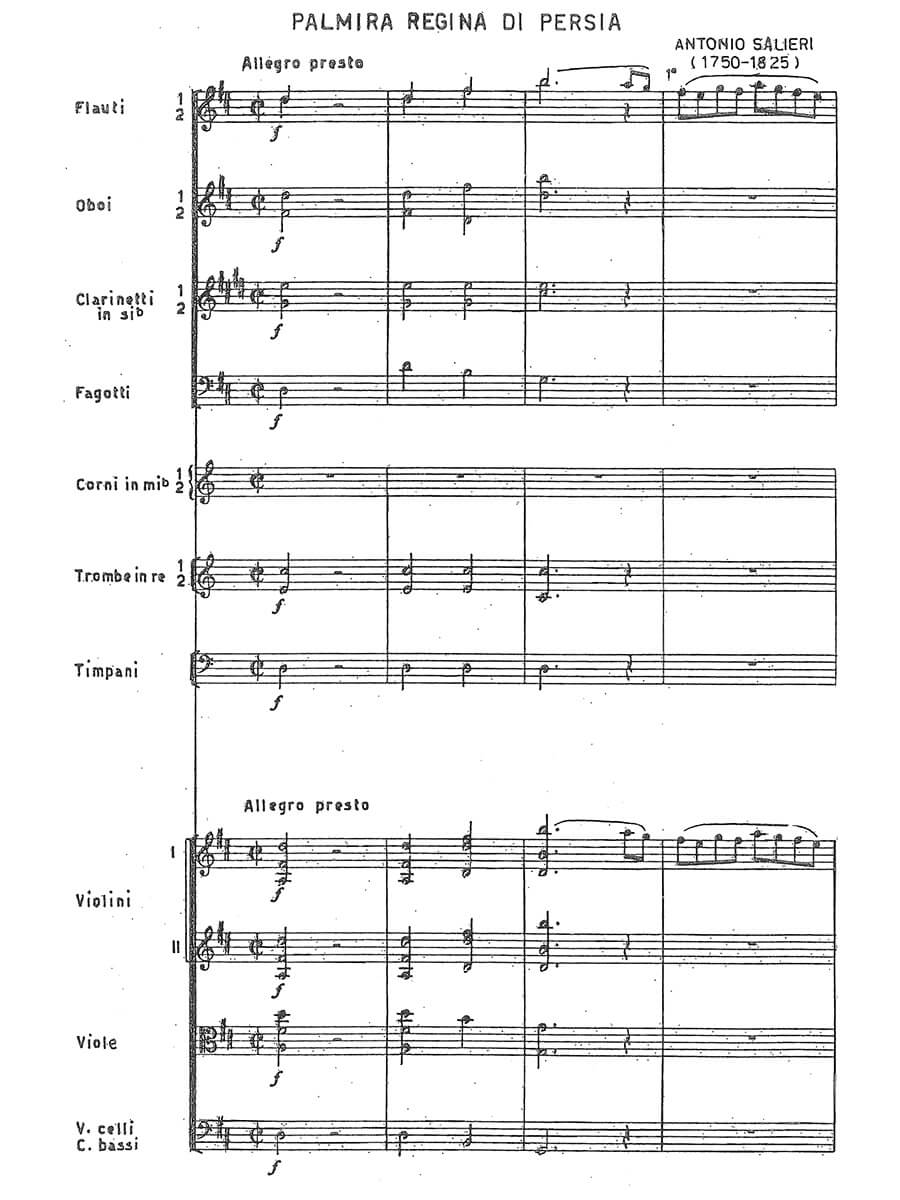

Palmira regina di Persia, overture

Salieri, Antonio

15,00 €

Antonio Salieri – Palmira regina di Persia

Overture

(born Legnago, 18 August 1750 – died Vienna, 7 May 1825)

Introduction

Antonio Salieri composed more than 40 operas during his 30 years of productivity as a creator for the musical stage. One of these is the heroic-comic drama in two acts Palmira regina di Persia with its libretto by Giovanni De Gamerra after Voltaire’s philosophical tale La Princesse de Babylone. The epicentre of this genre of Italian opera was Habsburg-ruled Vienna and this fact explains the “meeting of traditions of Italian, French and German theatre, the particular conditions prevailing [in the city’s] institutions as well as the close personal ties of individual librettists and composers to the metropolis.”1 The first performance took place on 14 October 1795 in Vienna’s Kaerntnertor Theatre.2 In the following years the work gained and kept its place in the European opera repertoire. The popularity of the opera at the time was obvious not only because of the translations of the libretto into different languages and the publication of extracts in various arrangements, but also from the fact that during the few years after the first performance the overture was already being published in various editions – besides marches and vocal numbers from the opera.3 The present score of the overture is a reproduction of the edition that appeared in 1978 by the publishers Boccaccini & Spada, who specialised in the rediscovery of works by Italian composers.

What follows is an overview of the whole opera, and in particular the reader will learn about its historical origins. In music history Salieri is renowned as a pedagogue. Counting amongst his most famous pupils were composers like Beethoven, Meyerbeer, Schubert and at the end also the young Franz Liszt. On the basis of his lively activity as an opera composer he can be regarded as an influential figure of the late 18th century in that area as well. His oeuvre includes all the various operatic genres of the leading European centres in his time: most of his early Italian operas can be classified as light comic and serious.4 He was the undisputed successor of Gluck in Paris in the field of ‘lyric tragedy’.5 The third area where his influence became established was Vienna during Habsburg rule. In 1788 emperor Joseph II awarded him the position of Court Musical Director which Salieri retained till his retirement in 1824.6 In the later years of his creative work for the theatre he transferred the management of the daily tasks of the opera to his pupil Weigl, committing himself in return to compose a new opera every year.7 The new collaboration with the librettist De Gamerra – earlier Salieri had worked with the dramatically talented Da Ponte – resulted, besides Palmira, in the other two works Eraclito e Democrito and Il moro.8

In Salieri’s biography Ueber das Leben und die Werke des Anton Salieri (On the life and works of Anton Salieri: trans.), which appeared only two years after his death, the Viennese composer and music author Ignaz Edler von Moser acknowledges the Palmira overture with the following words: “The overture of this opera is full of energy and one of Salieri’s best.”9

It is remarkable how Salieri creates an exceptional tension here with limited means: the beginning of the charming and lovely composition is based simply on a play around a triad, presented merely by the flutes and first violins in unisono. The manuscript shows a reduction in orchestration in comparison to the overture of Axur re d’Ormus. In all there are various similarities between Palmira and the also very successful Axur, as can be seen for example from the exotic subject matter.10 It appears at times that Salieri intended with Palmira to follow on from his earlier successes.11 In contemporary reviews too there are corresponding comparisons between the two dramatic works: for example in Warsaw a performance of Palmira was described as an accomplished and appealing copy of Axur – apart from the Polish translation of the libretto.12 The reviewer in an 1805 edition of the Allgemeinen Literarischen Zeitung likewise expressed strong criticism of the libretto, which had appeared in 1801 in a German version by Nestler in Hamburg. He stressed the “revolting features”13 of the libretto, and wondered if something of that kind should be inflicted on a sophisticated audience at all.14 There had been moreover “much pointless noise, much showiness for the rabble to gawp at, Moors, […] camels, warring peoples who troop over the stage, kings, priests, […] all of that comes and goes and flaunts or rumbles across the set, but of anything of true interest regarding the action and the characters there is almost no trace to be found’15

The general fascination for this opera together with its extraordinary visual effects would eventually turn it into one of the most popular works for the theatre from Salieri’s late creative period.16 Goethe for example was very appreciative of a performance in Frankfurt in 1797, abundantly praising the extravagant set designs.17 There is another description of a Palmira performance in the publication Letters of an Eipeldauer, which was quite popular at the time. The satirical stories in Viennese dialect authentically convey the delight with the scenery, even if it is most likely a mainly fictitious account: “The Italian opera Palmira […] can’t fail to be a hit with the Viennese, because they get to see a splendid entry parade and dwarfs and giants, and even camels and elephants. […] I thought they would never stop applauding and shouting bravo.”18

Translation: Babette Lichtenstein

1 Arnold Jacobshagen: Dramma eroicomico, Opera buffa und Opera semiseria, in: Herbert Schneider und Reinhard Wiesend (eds): Die Oper im 18. Jahrhundert (= Handbuch der musikalischen Gattungen, Vol. 12), Laaber 2001, p.88

2 Cf. Jane Schatkin Hettrick und John A. Rice: Art. Antonio Salieri, in: Ludwig Finscher (ed.): Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, People Vol. 14, Kassel [and elsewhere] 2005, Col. 847.

3 Cf. Ankonym: II. Neue Musikalien und Kunstsachen, in: Intelligenzblatt der Allgemeinen Literatur-Zeitung (1798), No.167 (November), Col. 1384.

4 Cf. Hettrick und Rice: Art. Antonio Salieri (see note 2 ), Col. 848.

5 Cf. Ibid. Col. 842.

6 Cf. Ibid. Col. 843.

7 Ibid. Col. 843-844.

8 Ibid. Col. 844.

9 I.F. Edlen von Mosel: Ueber das Leben und die Werke des Anton Salieri […]. Wien,1827, p. 149.

10 Cf. Hettrick und Rice: Antonio Salieri (see note 2), Col. 849

11 Cf. Ibid.

12 Cf. anonym: Die Oper der Polen, in: Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (1812), No. 20 (May), Col. 330.

13 Anonym: Kleine Schriften, in: Allgemeine Literaturzeitung (1805), Nr. 191 (Juli), Sp. 112., concerning the following words in the German translation of the libretto: „O ich sehe zum Erbarmen –/ Hier die Füße, dort die Arme,/ Hier den Kopf und das Gehirne,/ Dort das Herz, die Eingeweide,/ Hier den Magen, dort die Zunge,/ Hier die Augen, dort die Ohren,/ Hier – o du bist gewiß verloren./ Grimmig wird das Thier dich zausen,/ Wird mit Lust die Fetzen schmausen,/ Und ich lache dann dazu.“, ibid.

14 ibid. Cf.

15 Ibid., col. 111.

16 cf.. Hettrick und Rice: Art. Antonio Salieri (wie Anm. 2), Sp. 844.

17 cf.. Brief Goethes an Schiller vom 14.08.1797, in: Karl Richter [u. a.] (Hgg.): Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Briefwechsel zwischen Schiller und Goethe in den Jahren 1794 bis 1805 (= Sämtliche Werke nach Epochen seines Schaffens. Münchner Ausgabe, Bd. 8.1), München [u. a.] 1990, S. 389–390.

18 Ein Wiener [= Joseph Richter] (Hg.): Briefe eines Eipeldauers an seinen Herrn Vetter in Kakran, über d‘Wienstadt, Bd. 4, Wien 1796, S. 23–24.

For performance material please contact Boccacini & Spada, Rome.

| Score No. | 4043 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 44 |