Fantazias and other Instrumental Music

Purcell, Henry

30,00 €

Preface

Henry Purcell – Fantazias and Other Instrumental Music

(b. Westminster, 10. September 1659 (?) – d. Westminster, 21. November 1695)

Preface

“An English musician of more extensive genius than perhaps our country can boast at any other period of time.” This was how Henry Purcell — more than a hundred years after his death — was hailed by the famed English traveler and historian Charles Burney in his entry on the composer in Abraham Rees’s The Cyclopedia—one of the most comprehensive 19th-century encyclopedias in the English language (vol. 29, published in London in 1819). Purcell became a champion of English music already during his lifetime—a situation that has not changed in the twenty-first century, more than 300 years after his death. Purcell’s operas and odes continue to be performed across the world—works that have earned him the moniker of “the foremost composer of vocal music in English.” (Alan Howard, Compositional Artifice in the Music of Henry Purcell, OUP, 2020.)

Even in the eighteenth century, when the German-born George Frederick Handel became the leading composer in England, Purcell maintained his status. In comparing the two men, Charles Burney proclaimed Purcell’s vocal music “in the accent, passion, and expression of English words…as superior to Handel’s as an original poem to a translation.” Yet, this quote by Burney—and for that matter, any other quote by most others—shows an ostensible lack of awareness of many of Purcell’s instrumental works, most notably his music for the viol consort. Works that—as Peter Holman has asserted in his article on the composer in the New Grove—have become “cornerstones of the modern viol consort repertory.”

A child of the Restoration of Charles II, the precocious Henry Purcell climbed up the career ladder quickly. After an early career as a choir boy at the Chapel Royal (c. 1669–73), Purcell became the composer-in-ordinary to the monarch in 1677. In 1679, John Blow—the most prominent composer of the time—resigned his post as the organist of the Westminster Chapel in order to have Purcell succeed him. Finally, in 1682, Purcell was appointed organist of the Chapel Royal. He retained all these positions until his premature death in 1695.

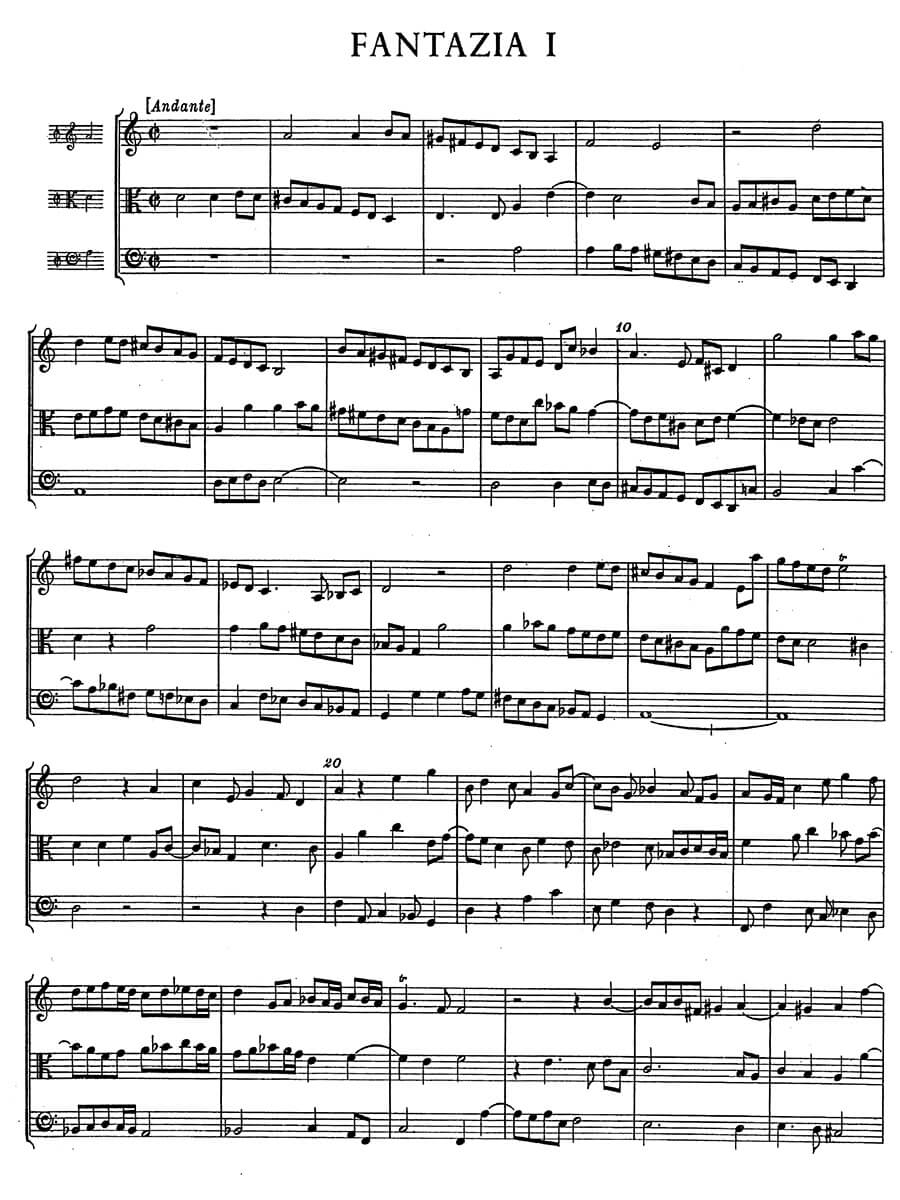

It must have been soon after assuming the job at the Westminster Chapel that Purcell began working on his works for the viol consort. His output for the medium consists of thirteen complete fantazias (three in three parts, nine in four parts, as well as the five-part “Fantazia on One Note”), one incomplete four-part fantazia, two In Nomines (in six and seven parts), and four pavans (in three parts). Judging from the blank pages of the manuscript containing the fantazias, Purcell seems to have intended to add more fantazias in 5, 6, 7, and 8 parts to his collection—an intention that was never materialized.

Described by Andrew R. Walkling (in The Ashgate Research Companion to Henry Purcell) as the “epitome of abstract music” in Purcell’s output, these works represent the very last examples in the English viol consort tradition that dates back to the first half of the sixteenth century. Though Purcell’s works seem to have been intended for consorts of viols, Peter Holman’s extensive research has shown that such works were often performed with organ accompaniment—often played by the composer himself—that doubled some or all of the parts. However, the lack of individual parts for most of these works have cast doubts on whether or not they were intended for performance.

All products of a youthful Purcell, the ten four-part fantazias bear a precise date (presumably the date of composition), most of which from 1680. Yet, as Burney’s aforementioned biography of Purcell shows, these works were not known to many. Even the biographer Nigel North, a contemporary of Purcell who also knew him personally, shows his lack of awareness of these pieces by recounting Matthew Locke’s fantasias as “the last of the kind that hath bin made.”

Among Purcell’s oeuvre, no other genre is as enigmatic as the pieces written for viol consort. The genesis—and consequently the reason for the relative obscurity—of these pieces has never been established with certainty. The most commonly accepted explanation is that most probably they were originally written as compositional exercises (a theory held by, among others, Peter Holman). They represent works written in a distinctly antiquated genre that went against the norms of the day, which were dictated by the new Italianate fashions—in form of the newly developed sonata, as well as the dominance of the members of the violin family. The new taste for Continental music was most pronouncedly declared by the monarch, Charles II, who is famously said to have professed his preference for music that he could tap his feet to (as reported by Roger North). Thus, the Chacony in G minor—another work about the genesis of which we know next to nothing—might have pleased the King due to its rhythmic vitality.

Purcell’s experiments and innovations in this collection of works vary widely. While his fantazias explore contrapuntal possibilities of the seventeenth century, Purcell’s In Nomines hark back to the sixteenth century — to a genre that began life in the 1520s in John Taverner’s works. In the Fantazia upon One Note, Purcell sets for himself the unprecedented challenge of creating a complex contrapuntal framework around a single-note cantus firmus (middle C, held in the tenor voice). Purcell’s pavans, on the other hand, might have represented another compositional challenge (as Peter Holman surmises): that of writing a pavan in every common key—a project that did not come to full fruition.

Purcell’s viol works mark the end of “the golden age” of the viol in England, a tradition that would lay dormant for almost 150 years, only to resurface at the turn of the twentieth century (this hiatus period has been vigorously studied by Peter Holman in his 2010 monograph.) They were only published in 1927 in an edition by Peter Warlock and André Mangeot. Thereafter, it took more than thirty years for a scholarly edition to appear. This was carried out by Thurston Dart under the auspices of the Purcell Society and published in 1959. The present volume makes available this edition, providing a tribute to Dart’s pioneering efforts in the field of scholarly early music editing.

Siavash Sabetrohani, 2020

Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 114 |