Il barbiere di Siviglia, ovvero La Precauzione inutile (Overture)

Paisiello, Giovanni

14,00 €

Preface

Giovanni Paisiello

(b. Tarent, 9. May 1740 – d. Naples, 5. June 1816)

Il Barbiere di Siviglia

Overture

Preface

Giovanni Paisiello was one of the best known and well-loved opera composers of the eighteenth century, even a favorite of Napoleon, for whom he later wrote masses, coronation music, and operas. In all, Paisiello wrote over 80 operas. His most celebrated opera today is Il barbiere di Siviglia ovvero la precauzione inutile composed in 1782 towards the end of his six-year stay in St. Petersburg. It was the success of this work that later inspired Mozart and Da Ponte to write the sequel to this story, Le nozze di Figaro, only four years later. Contemporary audiences were familiar with the story which was from Pierre-Augustin Beaumarchais’ famous Figaro trilogy, written in 1773, a comedy focused around the relationships between servants and nobility that makes use of commedia dell’arte characters. Le barbier de Séville is the first of the three stories. The popularity of Paisiello’s opera suggested that it was destined to become a classic and even Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, which premiered in Rome 30 years later, failed because Paisiello fans in the audience disliked that Rossini believed he could improve the opera. Today, however, it is Rossini’s opera that has overshadowed Paisiello’s because of its Romantic musical style with a larger orchestra and more ornate melodies.

Paisiello’s opera giocoso Il barbiere di Siviglia premiered in September 1782 at the St. Petersburg court where he was composing for Empress Catherine II. Beaumarchais’ Figaro plays’ recent positive reception at Catherine’s court was the impetus for the composition. The libretto is a free-form Italian adaptation of the French play and follows the exact order of its events. The opera even retains the structure of the play, including four acts instead of the typical two or three acts appropriate to comic operas at the time. The dedication to Catherine in the manuscript says that he intended to conserve the original story while also keeping it as short as possible, as operas were not to exceed one-and-a-half hours in her court. This restriction led to an unbalanced structure in the distribution and the types of musical numbers in the opera. The majority of the musical numbers are in the first two acts, and the aria to ensemble ratio (10 to 8), favors the ensemble in a way that was uncustomary for the period and genre. The court at St. Petersburg lacked a proper librettist for Paisiello to work with to adapt the play into a more suited format for opera. Generally, Giuseppe Petrosellini, who had previously collaborated with Paisiello, is credited with the creation of the libretto; although, it is questioned whether he would have approved of this unusual form. Regardless, Il barbiere was a hit and quickly spread throughout Europe playing in Naples, Vienna, Venice, Amsterdam, London, Madrid, and at Versailles. It was translated into French, replacing the recitatives with spoken dialogue from Beaumarchais’ play, and German. In Vienna it remained in the repertory for decades and received nearly one hundred performances between 1783 and 1804 in both German and Italian. Within three months of a performance of Il barbiere for the Neapolitan royal family, King Ferdinand appointed Paisiello to the post of compositore della musica de’ drammi (composer of musical dramas) which ended his stay in Russia and brought him back home to Naples.

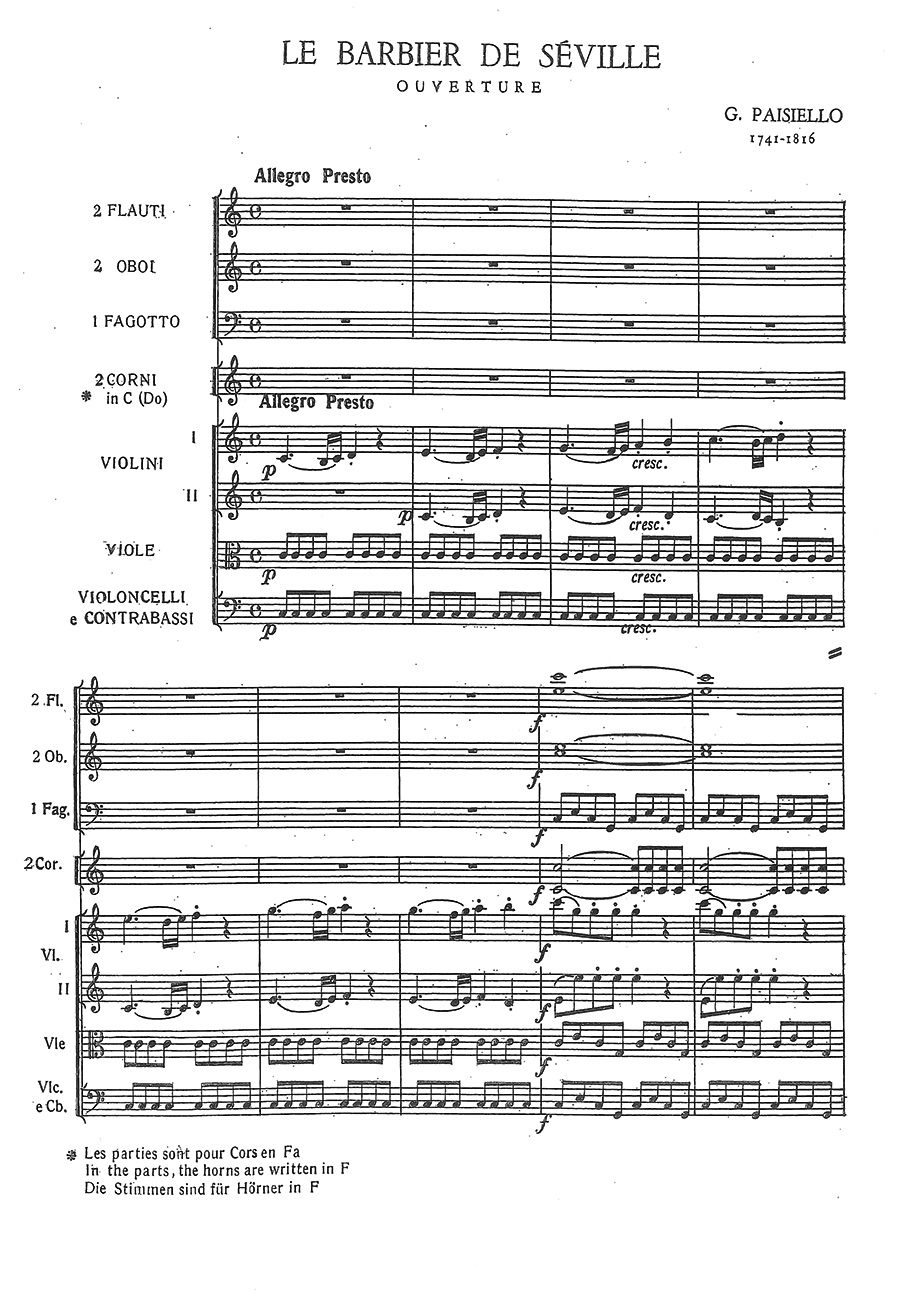

The overture to Paisiello’s Il barbiere, while seemingly simple compared to Rossini’s, is an exciting example of Galant music and a model for opera at the time. The work is written for a typically sized eighteenth century orchestra: two flutes, two oboes, one bassoon, two horns, violin, viol, cello and bass. It is a short one-movement piece in binary form with a bright and bubbly sound, consisting of varying staccato melodies. The beginning of the movement builds excitement as the lower strings play an ostinato pattern while the violins outline the tonic in short explosive bursts. The short opening motive in the violins repeats as the orchestra crescendos together introducing the audience to Count Almaviva’s anticipation as he waits to see Rosina on her balcony at the beginning of the opera. This motive returns, slightly adjusted, later in the opera as the six measure introduction of Figaro’s first aria “Scorsi già molti paesi” creating a slow build as he lists all the places he has been since he left the count’s service. The next motive in the violins at m. 16 is more extensive and has a starker contrast between legato and staccato. This motive also returns later in the opera during the second act trio “Ma dov’eri tu stordito” when two of Bartolo’s servants are uncontrollably sneezing and yawning after being drugged by Figaro. Within the overture, this motive foreshadows the slapstick to follow. These short motives add excitement and drama to the overture, preparing the audience for an evening of laughter.

The musical interest of this piece also comes from its dynamics and rhythms. In the overture, as well as throughout the whole opera, Paisiello uses rhythm to drive the drama, frequently employing repeated eighth notes in the lower strings as the upper voices contribute shorter, playful motives. Dotted rhythms appear extensively in the overture to provide the light and joking air. Throughout Paisiello also makes use of dramatically changing dynamics and frequent crescendos. The suddenness of the fortepiano (which occurs nearly every other measure starting in m. 16) adds to Almaviva’s anticipation to see Rosina.

Overall the harmony is simple and straightforward. This is a product of both Paisiello composing for a non-Italian speaking court and of Gluck’s reform operas. The language barrier required a degree of simplicity in the music in order for the story to be understood, but the simplicity is also a result of Gluck’s reforms which influenced the focus of opera back to the drama. Music was becoming equal with and informed by the text. While much of the music from this opera is subservient to the text in the same way that Gluck strived for, Paisiello’s rhythmic flair and fun dynamics always feed into the drama and comedy. The autograph manuscript of this work can be found at the Biblioteca del Conservatorio di musica S.Pietro a Majella in Naples

.

Amanda Jacobsen, 2018

For performance material please contact Heugel, Paris.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Overture |

| Pages | 24 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |