Die Leiden des Herrn Op. 13 / Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir Op. 54 / Auf meinen lieben Gott Op. 61

Mendelssohn, Arnold

26,00 €

Arnold Mendelssohn – Three Sacred Choral Works

(b. 26. December 1855, Ratibor — d. 19 February 1933, Darmstadt)

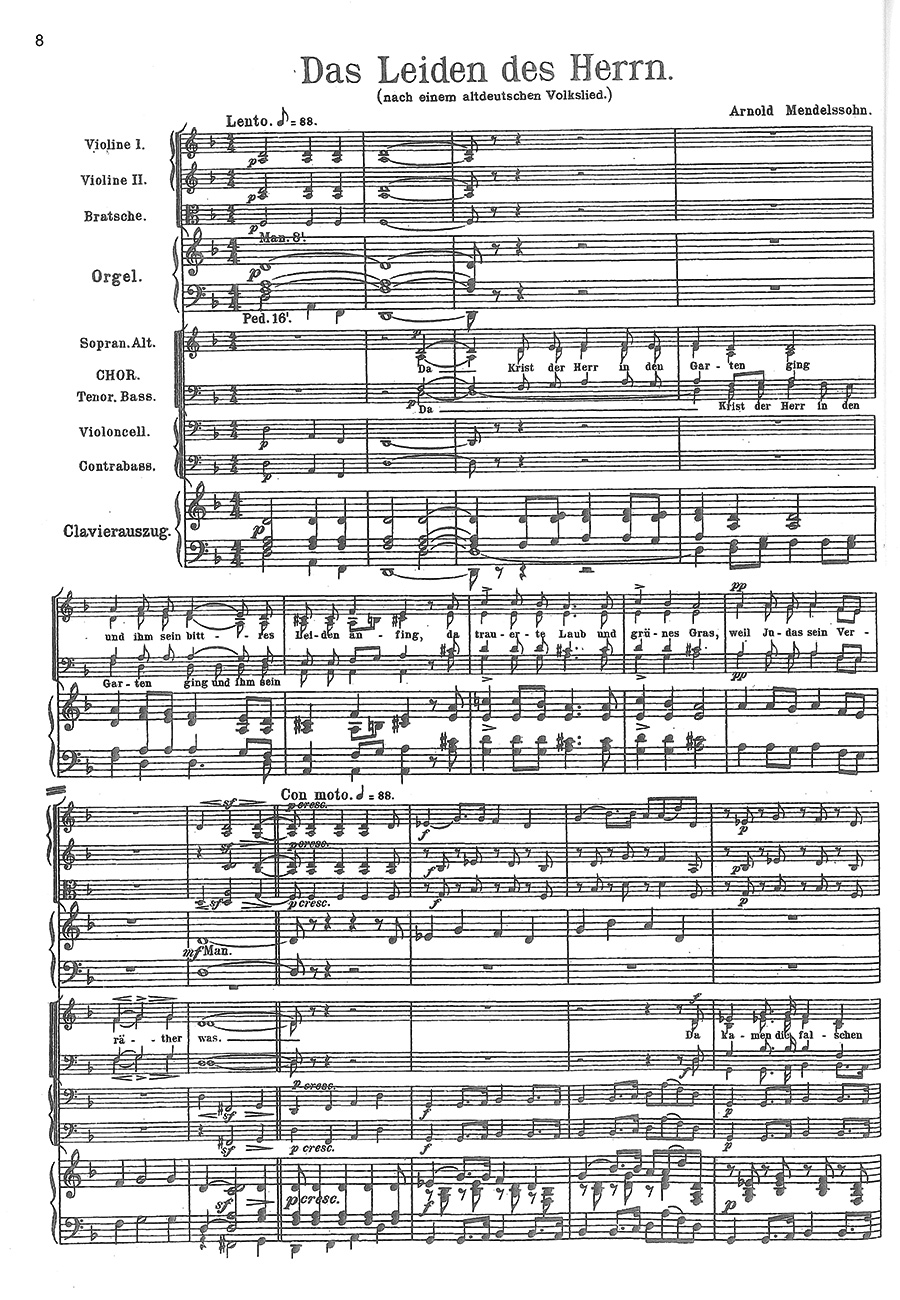

Die Leiden des Herrn, op. 13 (1900)

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir, op. 54 (1912)

Auf meinen lieben Gott, op. 61 (1912)

Preface

One associates with Lutheran sacred music with the name Mendelssohn, from the simple choral setting to the full-length oratorio, as well as a strong sense of connection with its traditions. Often enough the Latin phrase nomen est omen has a certain rightness to it, and it would hardly be suprising to learn that the composer Arnold Ludwig Mendelssohn, whose father was a cousin of the famous Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), was both in his own time and up to the present recognized first and foremost as a composer of church music. But this does not do full justice to the man. He was especially well regarded and successful as a composer of songs, and his three operas and two works of incidental music were at least succèses d’estime, and his chamber music both sold well and was often performed. Only his orchestral works never quite got a firm fotting in the concert hall – of his three symphonies (disregarding student works) not one appeared in print, and it remains for the future to decide whether symphonic thought did not especially suit him, or whether the composer of sacred music was not taken especially seriously by the leading forces in the concert life of his time.

The best explanation for Arnold Mendelssohn’s fame during his lifetikme and small but firm place in today’s music world comes from Mendelssohn himself. After all, one also associates with his name the world of thought in general: another of his relatives was the philosopher and theologian Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786), and there is also a certain rightness to the fact that the best-selling work of Arnold Mendelssohn’s was a book, the publication of which he never intended. This was Gott, Welt und Kunst (God, World and Art), a volume of notes the composer made to himself, collected Wilhelm Ewald and published posthumously in 1946, by Insel. (Ewald’s arrangement of the notes is strongly reminiscent of the volumes of Karl Kraus’s aphorisms, which is actually quite appropriate to the material.) Like more than a few composers – not coincidentally among them his most famous pupil, Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) – he found in Johann Sebastian Bach an identification figure: “It is different now. Bach could become so great because at his time the Church was outwardly and inwardly a formative element in the circle in which he belonged. In the Church the entire man found support on the one hand, expression on the other. In addition, it offered him, to put it in a banal manner, an audience that stood on the same ground he did – a similar condition to the one obtaining with regard to Attic tragedy. When the genious stepped into the circle, the possibility of greatest achievement was present. It is different now. Ever since man has frivolously dismissed the Church, the tie that marked the boundary of a truly shared national culture is absent. [ . . . ]”

It is therefore hardly surprising that Arnold Mendels-sohn’s musical activity seldom stepped outside the circ-le of church music. After concluding his music studies at two Berlin institutions (the Royal Academic Institute for Church Music and the Academic School for Musical Composition) he was named organist and choral director of the Lutheran congregation in Bonn (1880-1882). In Bonn he became friends with the theologians Friedrich Spitta (1852-1924) and Julius Smend (1857-1930); and from this time dates the beginning of his lifelong interest in the tradition of Lutheran church music, an interest he cultivated for the rest of his life, and which resulted in several editions of past musics. From his pen came numerous practical editions of sacred choral works of the late renaissance and early baroque (Orlando di Lasso, Hans Leo Hassler, Claudio Monteverdi, Heinrich Schütz), and starting in 1928 he edited, along with Friedrich Blume (1893-1975) and Willibald Gurlitt (1889-1963) the critical complete edition of the musical works of Michael Praetorius.

After Bonn was a series of further and increasingly important appointments: Music Director in Bielefeld; teacher at the Cologne Conservatory (in theory and organ); and Master of Church Music of the Hessian State Church in Darmstadt (1891-1912). He remained in Darmstadt almost without interruption until the end of his life. Granted, he accepted a position as choral and composition instructor at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt am Main in 1912, where his supportive nature and indulgent attitude with regard to stylistic aspirations (despite strictness in matters of form – and his physically imposing appearance) inspired the lifelong devotion and gratitude of his pupils, among them, in addition to Hindemith, were Kurt Thomas (1904-1973) and Günter Raphael (1903-1960). He remained hardly a year in Frankfurt: ill and probably overburdened – for he had not entirely given up his duties in Darmstadt – he retreated to Darmstadt, where he henceforth devoted himself primarily to composition. In his last decades he was practically buried under a mountain of honors: in addition to being named a member of the Berlin Academy of Arts (1919) and receiving the Georg Büchner Prize of the city of Darmstadt (1923) and the Beethoven Prize of the Prussian State Academy (1928), he was granted numerous honorary doctorates and honorary citizenships. He died of a heart attack hardly three weeks after the accession to power of the Nazis, who banned his works on account of the ancest-ry of their creator.

As a composer, Arnold Mendelssohn represented, especially in those works of his intended for church use, a pronouncedly conservative, even anachronistic direcion. One ought not assume, however, that he was entirely averse to the stylistic means of late romanticism or early modernism. As Arnold Werner-Jenson writes in the second edition of Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: “The deliberate, almost registrational employment of diverse stylistic means” – he refers, first and foremost, to strongly extended tonality and folklike diatonicism – “belonged to Mendelssohn’s compositional personality.” In the three works presented here, a style indebted to Bach predominates, especially in the contrapuntal voice leading; even the frequent minor-key chromaticism stays within limits the church singer will usually find comfortable. One can, however, find traces of later compositional thought frequently enough in the means of expression, especially in the accompanying figurations.

Although the compositions of Arnold Mendelssohn, especially his choral works, are not infrequently recorded, the three works collected in this volume still await their first recordings.

Stephen Luttmann, 2010

For performance materials please contact the publisher C. F. Peters, New York or Reprint of a copy from the Musikab-teilung der Leipziger Städtische Bibliotheken, Leipzig.

| Score No. | 1005 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | A Cappella |

| Pages | 94 |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |