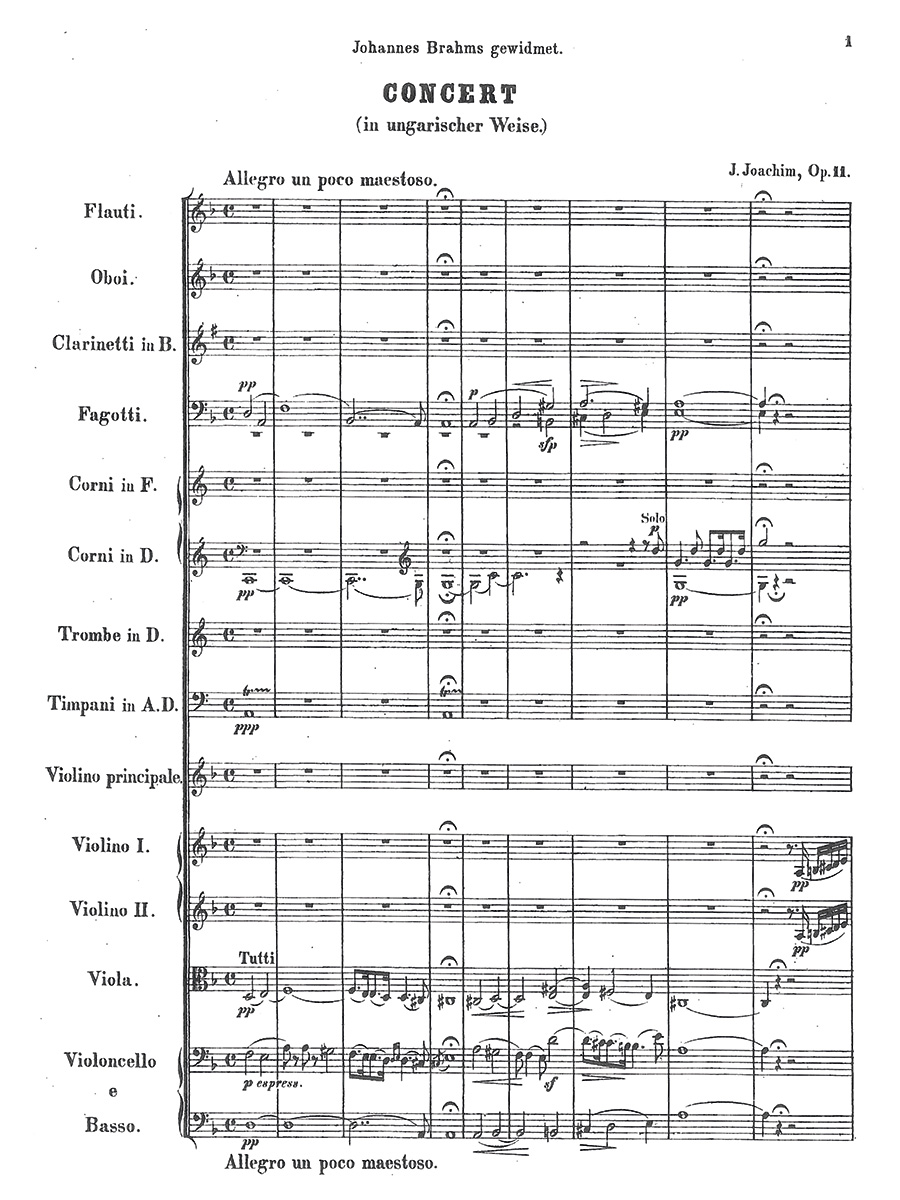

Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor “in ungarischer Weise” Op. 11

Joachim, Joseph

32,00 €

Preface

Joseph Joachim

Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor “in the Hungarian Manner,” op. 11

(b. Kittsee, 28 June 1831 — d. Berlin, 15 August 1907)

Dedication

Johannes Brahms

Composed

Hanover, Summer 1857

Premiere

Hanover, March 24, 1860; published: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1861

Preface

Joseph Joachim’s Concerto in D Minor, op. 11 “in ungarischer Weise” has long been considered one of the composer’s finest works, easily overshadowing several of his other compositions in the Hungarian style: an early fantasy on Hungarian themes (ca. 1850), and a Rhapsodie Hongrois for violin and piano (1853, written together with Franz Liszt). It is a substantial work that enjoyed great popularity during Joachim’s lifetime, though he himself ceased performing it in his later years, due to its exceptional length and difficulty. Indeed, it was said that Joachim was not the work’s best interpreter, that distinction belonging to Wilhelmj or Laub, or later to Flesch, who played it with great sentiment and Gypsy-like abandon. Joachim’s early Hungarian pieces were typical virtuoso products; the “Hungarian” concerto, on the other hand, is a symphonic work of grand design and elaborate execution — a rare and important link between the classic works of Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn, and the late 19th-century concerti of Bruch, Lalo, Goldmark, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Dvorak and Saint-Saens.

The years leading up to and during the composition of the concerto were a time of crisis for symphonic composition of all sorts, when the symphony itself was in eclipse. As Carl Dahlhaus has noted, the rigorous post-Beethoven requirements for writing music in ‘grand form’ had become inhibiting; for a generation, this led to an absence of “any work of distinction that represented absolute rather than programmatic music.” By mid-century the symphony per se had become moribund: in the “progressive” aesthetic of the New German School, compositions in traditional forms were derided as dry, academic and outmoded. In his essay Oper und Drama, Wagner famously — and prematurely — sounded the symphony’s death-knell.

Under these circumstances, the concerto offered traditionally-minded composers a genre of “absolute music” that allowed considerably more individuality and freedom of expression — more latitude for innovation in form — than the symphony, while stopping short of employing extra-musical programs. A prime example of this is Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26 (1866). The first movement of Bruch’s concerto is unusual by any standard: a free introduction (Bruch uses the Wagnerian term Vorspiel) to the central slow movement that is the real raison d’être of the piece. Bruch had compunctions about whether a work so unorthodox in form could properly fit the genre, but was reassured by Joachim: “Finally, as to your ‘doubt,’ I am happy to say that I find the title Concerto to be in any case justified — the last two movements are too greatly and too regularly developed for the name ‘Phantasie.’ The individual constituents are quite lovely in their relationship with one another, and yet sufficiently contrasting; that is the main thing. Furthermore, Spohr also called his Gesangs-Scene ‘Concerto!’”

It is precisely this freedom — this ability to break free of the shadow of Beethoven and “grand form” while resting on the authority of accepted models — that appealed to composers of a conservative bent and allowed the symphonic violin concerto, as a genre of absolute music, to retain its creative interest, and maintain a provisional hold on the public at a time when the symphony itself was in eclipse. As Joachim mentioned in his letter, Spohr (1816) provided an early example of unconventional form — a concerto cast as an operatic scena. Mendelssohn’s concerto (1845), which influenced subsequent composers as late as Sibelius, is replete with formal innovations (the lack of opening tutti in the first movement, as well as the centrally-placed cadenza leading to the unusual recapitulation, etc.).

Equally important, the concerto offered composers the freedom to explore certain more lyrical or characteristic moods — moods that were congenial to the era, but that lay outside the aesthetic norms of the symphony, or were problematic if subjected to the formal processes that the symphony required. A few characteristic symphonies, full of “local color” such as Goldmark’s Ländliche Hochzeit (1876), enjoyed a period of popularity, but stood apart from the rigid expectations of the genre, and eventually dropped from favor. On the other hand, characteristic concerti such as Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole or Bruch’s Schottische Fantasie, or Wieniawski’s Concerto no. 2 in D Minor, with its Finale à la Zingara, continue to be staples of the violinist’s repertoire. Joachim’s Concerto “in ungarischer Weise,” is a significant example of these “characteristic” concerti. Though early, it was considered by Carl Flesch to be a high point of the genre: “the most outstanding creation that a violinist has ever written for his own instrument.” Written during the same years as Wieniawski’s, it is also in D Minor, and also ends with a Finale à la Zingara — a wild Gypsy moto perpetuo introducing an extended, virtuosic rondo. With his op. 11, Joachim goes well beyond Wieniawski, however, taking the traditional three movement concerto form and extending and freely recasting it into a broad symphonic portrait of his native Hungary, at once personal and idealized — a full forty-five minutes of the greatest virtuosity placed at the service of the most evocative poetry.

The Style Hongrois — the Hungarian style — has a long history in Classical music going back to Haydn, if not before. Its characteristic moods and gestures were adapted by 19th-century composers as dissimilar as Liszt and Brahms, who reveled in the freedom, nostalgic melancholy, and passionate abandon native to the style. Joachim was, of course, Hungarian by birth, though like Liszt, he was taken from his native soil at an early age. He spoke little Hungarian, and he regarded the whole of Magyar culture with a wistful, romantic gaze. The Hungary of Joachim’s birth was still a land untouched by progress. Under Habsburg rule since the defeat of the Turks, it was poor, virtually without infrastructure, industry, banking or trade — a puzzle of secluded villages and feudal demesnes. From earliest times, the plains of Hungary had been swept by successive waves of invasion and immigration, and the resident population bore the impress of many cultures, from ancient Celts and Romans to modern Magyars, Slovaks, Germans, Roma, Turks, and Jews. Scarcely a third of the population spoke Hungarian — the common language of the upper classes was Latin. In this confusion of ethnicities, Joachim made no distinction between “Hungarian” and Gypsy vernacular music. Like other classically-trained musicians, he associated the undifferentiated “Hungarian” style with an exotic, uninhibited, and proudly semi-civilized folk. This is apparent in a November 1854 letter from Joachim, at that time concertmaster in Hanover, to his countryman Liszt: “I was in the homeland,” he writes. “To me, the heavens appeared more musical there than in Hanover.

Robert Eshbach, 2016

For performance material please contact Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden..

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Violin & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 140 |