Quintette à vent for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon (score and parts, first print )

Huybrechts, Albert

30,00 €

Preface

Albert Huybrechts – Quintette à vent for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon (1936)

(b. Dinant, 12 February 1899 – d. Woluwé-Saint-Pierre, 21 February 1938)

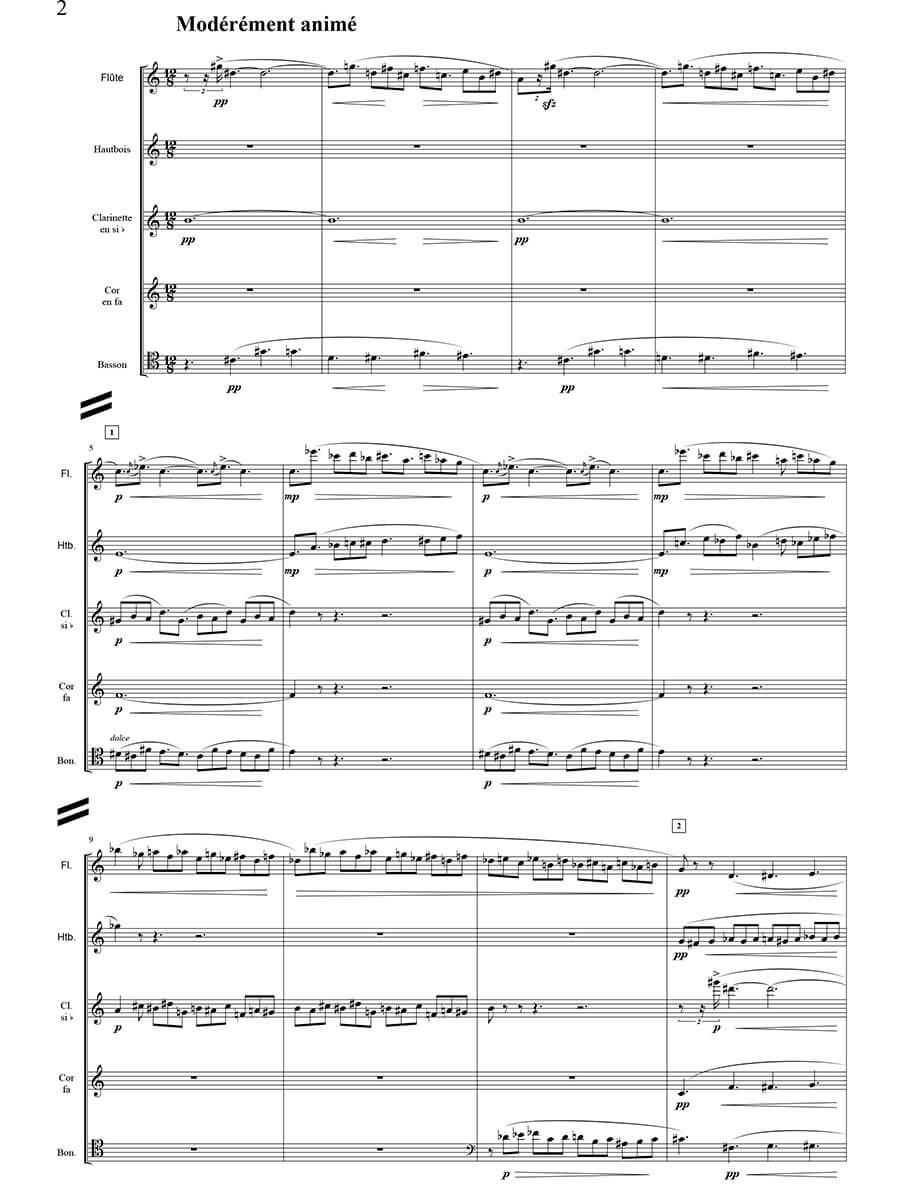

I Modérément animé (p. 2) – attacca:

II Très lent (p. 8) – attacca:

III Vif et léger (p. 14)

Belgium is a deeply dysfunctional country, a nation traumatized by the split between its Flemish and Walloon wings. It is also a country with many “skeletons in the closet.” One of these skeletons has recently been gradually disinterred: Albert Huybrechts, by far the most riveting figure of Belgian modernism. Huybrechts has even been honored by a website authorized by his descendents, which, if short on background information, at least contains a complete catalogue of his slender oeuvre and an overview of the commercial recordings of his music.

Huybrechts’s father died just as the boy reached maturity, and he had to assume responsibility for supporting his mother and siblings, leading a life in the shadow of success. Things did not always look this way, for in 1925 he received the Coolidge Prize for his freshly completed Sonata for Violin and Piano (it would become his most frequently performed work) and, five days later, the first prize at the Ojay Festival for his First String Quartet. Lasting success was just within his reach, only to slip immediately from his grasp. Undaunted, he used the always scant time at his disposal to continue composing, generally chamber music of exquisite refinement, but also orchestral works, songs, and a theater score for Aeschylus’s Agamemnon which, apart from the prelude, has vanished. No sooner had he finally been appointed a professor at Brussels Conservatory than he died of kidney failure.

The son of an orchestral cellist, Huybrechts trained to become an oboist (which surely goes some way to explain his great predilection for the woodwinds) and won first prize at the Conservatory at the age of sixteen for his instrumental prowess. He was taught composition by Joseph Jongen (1873-1953), Belgium’s highly acclaimed successor to César Franck, and went on to acquire a solid mastery of his craft. His early works reflect this sphere of influence, to which was added an obvious admixture of Debussy. Then, step by step, he considerably enlarged his stylistic spectrum, imbibing the new achievements of Stravinsky, Bartók, Schoenberg, Milhaud, and Honegger, among others. But the music he felt closest to was that of Albert Roussel, as is manifest in his headstrong truculence, his off-kilter harmonies and rhythms, his radical focus on the inner life of motivic evolution, devoid of extra-musical associations, his striking blend of themes and figuration into a sort of neo-classical polyphony which, one might say, smuggles the contrapuntal art of the early Netherlandish masters incognito into a coarse expressive idiom, and his almost flagrant indifference to sensational modernism as an end in itself. (Incidentally even Roussel, despite his sterling quality, high reputation in specialist circles, and top-caliber performances, ultimately failed to attain the popularity of Fauré, Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, or Poulenc.)

Huybrechts’s mature creations of the 1930s are constantly distinguished by a density, rigor, and hermetic grandeur otherwise encountered, in this regularity, only among the greatest masters of the art. At the same time, for all the savagery and vibrant eloquence of the fast movements, they are pervaded by a deeply introverted, bleak inflection that suggests a desperate struggle against loneliness while never yielding to sentimental resignation.

Huybrechts’s approach to neo-classicism goes beyond Stravinsky’s dispassionately constructed puzzles, Poulenc’s picturesque stylistic fractures or Milhaud’s playful bitonality. He fully assimilated their vocabulary and grammar while invariably writing from a holistic stance that conveys an alert, actively integrative mind with an indissoluble amalgam of technical mastery, seriousness of purpose, humor, sarcasm, drama, tragedy, and tender intimacy. His “late” works (if the works of a man in his mid-thirties can be called late) are infinitely remote from any semblance of French bucolics. Much like Roussel, but in an entirely different way, he found his own path, which incorporated the full range of dissonance and yet, for all its deliberate vagaries, never descends into clogged aridity and resists easy classification into any of the terminological pigeonholes of the day, whether neoclassicism or Neue Sachlichkeit. His music blends elements of Expressionism and Impressionism in a unique manner that both stands at and transcends the cutting edge of his day.

Huybrechts’s Wind Quintet of 1936, encompassing three movements in a single arc, is one of his most masterly creations, generating an abundance of energy while evincing perfect balance of form. In the middle movement he bridges the ages by interweaving the archaic melody of the Dies irae, which forms the unyielding axis of the events at the center of this marvelous quintet and projects its unequivocal message into the world: every day, not only in Belgium but elsewhere as well, constitutes a new Dies irae which we must face with all the constructive forces at our command. Huybrechts’s music can also teach us not to flee from the implacable essence and radical beauty of the reality hidden in the quotidian masquerades of ordinary existence. It does so in the unpretentious language of truly great music that stands in no need of seeming prettier, more sacred or more extravagant than human life itself.

Huybrechts’s Wind Quintet appears here in a new edition prepared and critically annotated by Wolfgang Pickhardt. Though largely unknown, it is one of the most precious and distinctive works for this combination of instruments, a genre richly cultivated by great masters.

Christoph Schlüren, October 2018

Score Data

| Genre | Chamber Music |

|---|---|

| Size | 225 x 320 mm |

| Specifics | Set Score & Parts |

| Printing | First print |

| Pages | 64 |