Aufklänge for orchestra

Hausegger, Siegmund von

32,00 €

Preface

Siegmund von Hausegger – Aufklãnge (Resonances)

(b. Graz, 6 May 1872 – d. Munich, 10 October 1948)

Preface

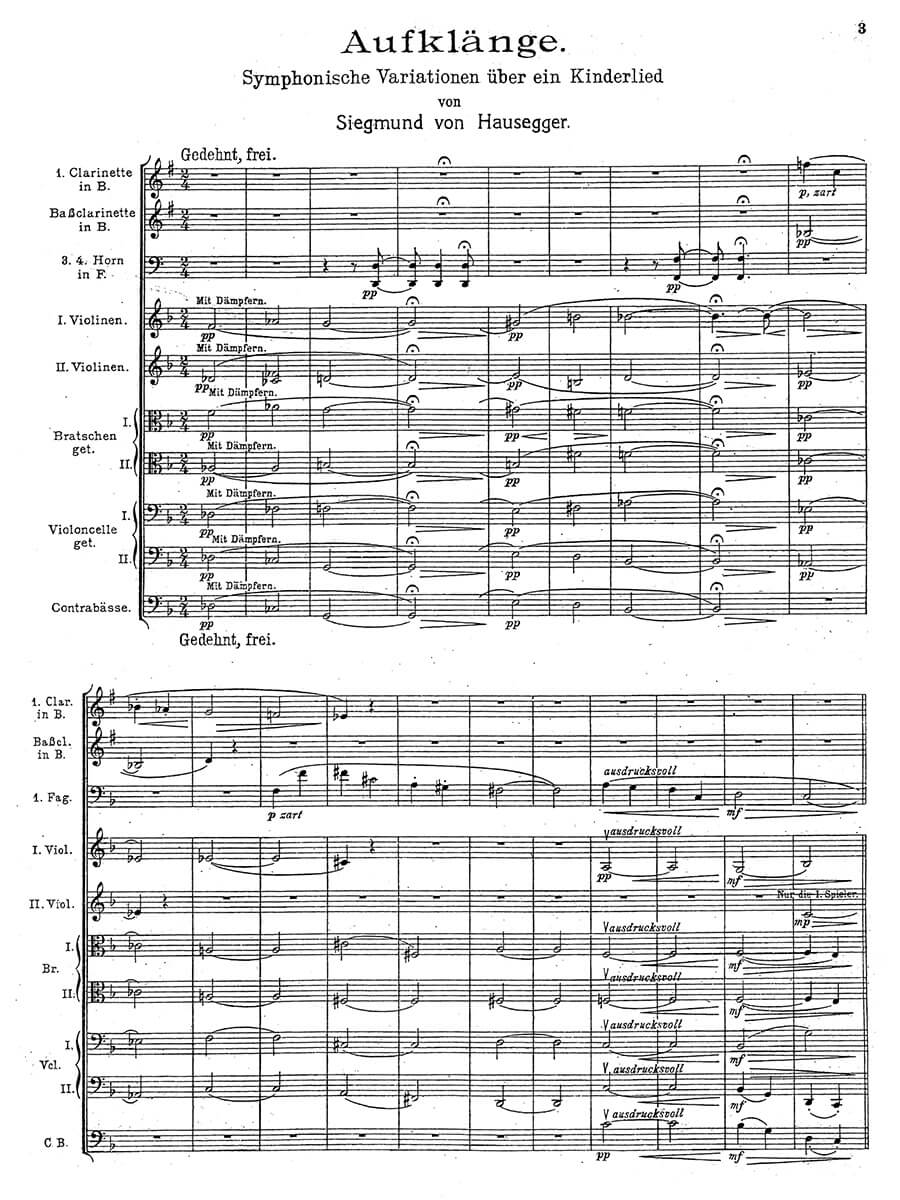

Aufklãnge (Resonances, 1917) is a set of variations on the traditional nursery song “Sleep, Baby Sleep”. The text is:Schlaf’ Kindchen schlaf’ Sleep baby sleep

Der Vater hüt’t die Schaf While father guards the sheep

Die Mutter schüttelt’s Bãumelein And mama rocks her baby’s bough

Da fãllt herab die Trãumelein Till tiny dreams fall o’er thee now

Schlaf’ Kindchen schlaf’ Sleep baby sleepHausegger thought of the work as a complement to his 1911 Natursymphonie (mphMusic score 4173). The symphony brought man into a cosmic relation with Nature. Aufklãnge is man within his own subjective experience. Dedicated to his 4-year old son Friedrich, the music reflects the “dream-like optimistic and deeply reverie-like feelings of a father beside his child’s cradle”. The plan of the 30-minute work is a theme with eight variations, followed by an elaborate scherzo and fantasia the composer describes as “the roaring song of a visionary view of life.”

The music begins with calm string harmonies that serve both as an introduction and to establish the fundamental tonality of F major. We first hear the theme itself on the English horn (7 bars before Cue #1). Variation 1 is so brief as to be really a transition to Variation 2. (9 before #3). This is in a faster 6/8, like a barcarolle. Its predominant colors are high woodwinds and celeste, with a handsome cello countermelody. Variation 3 (8 before #4) is more tender, with an especially attractive clarinet and violin duet. It builds to a crescendo, after which horns play the transition to Variation 4 (8 before #6). Over the lullaby, itself in B minor, the upper strings play an eloquent counter-theme in the relative D major.

Variation 5 (10 before #13) begins with overlapping dialogue; Hausegger writes “the bassoons clumsily stumble behind one another.” The orchestra then snatches up the theme “with arrogant menace”, building to a powerful tutti suddenly broken off via a downward-sweeping harp glissando. Variation 6 (11 before #16) “a spooky extended scherzo” begins with the theme on the celeste, accompanied by harp syncopations and rustling string figures. A central segment uses the first two and last four beats of the lullaby in retrograde (2 after #18), leading to agitated chromatic figures. The stormy pace continues, peaking on an Ab seventh chord undercut by a D pedal in the bass. There’s a reprise of the variation’s shadowy opening bars. Variation 7 (8 before #24) is a pensive adagio in Db major, the music including a note of anguish. Variation 8 (8 after #28) in A major combines the first bar of the theme with a flute countermelody that’s part of the lullaby in retrograde. The general lightness of this variation contrasts with its predecessor. The vision of the child’s song fades and the music via a deceptive cadence returns to F major.

Rubato bird-calls derived from the lullaby introduce the latter section of the work (3 before #33). The orchestra gradually joins in, then the violas begin a fugato passage (“very fiery”) based from one of the bird-calls (#36). The music achieves a climax in C major followed by a “love song” for solo violin (#39). A second assertive fugal passage appears, derived from the subject of the first one. The bird-calls chime in. At #43 after “the child’s laughter vanishes”, another broad violin melody introduces a second episode. This includes a compressed fugato segment, culminating in a grand tutti passage (#53). “Serene child-like innocence subdues the world!” Amid all this activity, there’s scarcely an accidental; it’s one of Hausegger’s most diatonic passages. After the waves of sound subside, the coda, using the first bars of the lullaby in augmented phrases leads to an elegiac violin theme (8 after #58). There are echoes of the bird-calls before the closing bars in F major. These include muted reminiscences on the horns and harp of the last phrase of the lullaby (recall its words; “Sleep, baby sleep”).

We could consider Aufklãnge as a counterpart to Strauss’ Domestic Symphony but in a more sublimated form ~ no alarm bell or yowling baby. We also hear Mahler’s influence. Though it may have simply been Hausegger wanting lighter textures, the absence of lower brass recalls Mahler’s 4th Symphony (Hausegger was at its premier). The critical role of the bird-calls in the second part also pays homage to a Mahler trait. After this, Hausegger wrote no more significant works. Partly this was due to his increasing success as a conductor, which took up ever more of his time. Yet I incline to think it’s also a case of the times being out of joint. We see a similar drying up in contemporaries as different as von Schillings and Sibelius. To someone with Hausegger’s idealism and his veneration of the musical art, the paths taken by, say, Krenek or Weill must have seemed like sacrilege. Alternately, Schőnberg and his 12-tone language would have struck him as denying the very notion of inspiration. Thus he sought refuge in the classics, devoting the rest of his life to their interpretation and to the education of a new generation. One does one’s best and hopes for vindication.

Quotations in the above text are from von Hausegger’s guide to Aufklãnge, published in his Betrachtungen zur Kunst, Die Musik, Leipzig 1920. The work has been recorded on cpo 777-810. Anyone interested in further information about this fine composer can see my Website vonhausegger.com

Don O’Connor 2019

For performance material please contact Ries und Erler, Berlin.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 128 |