La Conversione di Sant Agostino, Oratorio

Hasse, Johann Adolph

31,00 €

Preface

Johann Adolph Hasse

(b. Germany, March 25, 1699, d. Venice, December 16, 1783)

La conversione di Sant‘ Agostino

Preface

Johann Adolph Hasse was an obedient son and went into the family business: music. From childhood he trained as a singer and composer, and he earned his first job as a tenor at the court of Brunswick in 1719. Following the regional success of his first opera Antioco (1721), in which Hasse sang, he departed in 1722 for his grand tour, landing in the musical capital of the time, Naples. His association with the greatest singers of his age began there and he fine-tuned his skills as a composer under the watchful eye of Alessandro Scarlatti. His successes in Italy quickly became the talk of Europe and with his friend and colleague, Pietro Metastasio, he defined the genre of opera seria for a generation.

Royal courts throughout the continent coveted Hasse, a celebrity of his time, and in 1730 he accepted the position of Kappellmeister at the court of Dresden. Though Hasse’s international fame came from his vast operatic output, he also composed a remarkable body of sacred music. On March 28, 1750, Hasse presented his oratorio La conversione di Sant‘ Agostino in the chapel of the royal palace in Dresden. Electress Maria Antonia Walpurgis penned the libretto, based on a Jesuit drama by Franciscus Neumayr. The Dresden premiere was followed by numerous performances of the oratorio in Leipzig, Hamburg, Mannheim, Padua, Rome, Riga, Prague, Potsdam and Berlin, a testament to the work‘s popularity in the latter half of the 18th century. The work comes to us from a manuscript located at the Sächsische Landesbibliothek in Dresden, Germany.

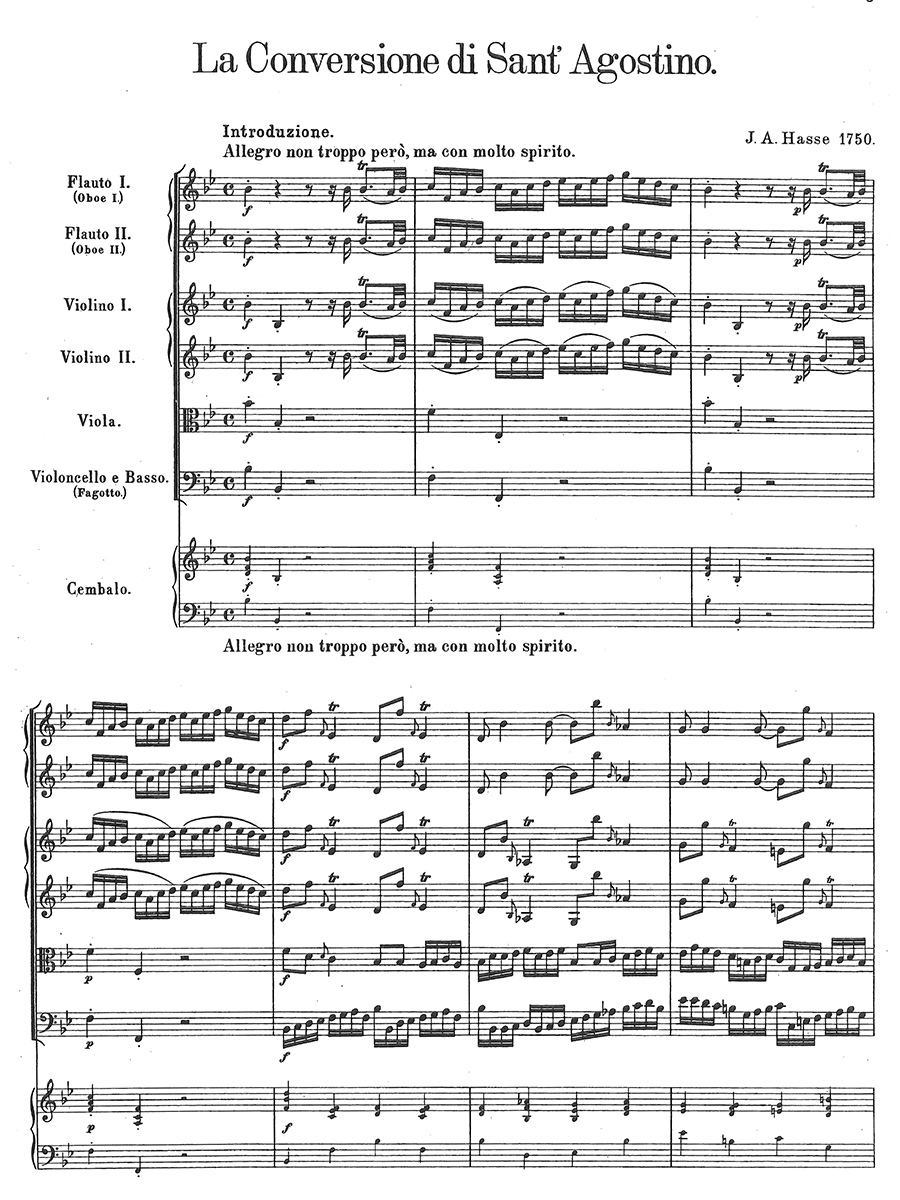

Hasse begins La Conversione di Sant’ Agostino with an orchestral introduction that establishes the work‘s tonal center in the key of B-flat major, with most arias composed within related keys. From the grandeur and dynamic intensity of the Introduction comes the first vocal entrance of the oratorio. The listener acts as a voyeur into a conversation between Simpliciano (tenor), a priest, and Monica (soprano), the mother of Saint Augustine of Hippo, in which Monica expresses her fears that her son may never change his wicked ways. This urgent desire becomes the core dramatic theme throughout the oratorio with Alipio (alto), the friend, and Navigio (bass), the brother, serving to intensify the desperate desire for conversion. The role of Saint Augustine (alto) is secondary to that of his mother, Monica. Saint Augustine only has two arias, both dealing with his desire to find release from his sinful ways. His conversion is explicitly stated in the Part Two aria in which he begs God to look upon him with compassion following the censure of his own heart.

Hasse uses formal conventions to underscore the drama throughout the entire oratorio. The first aria sung by Monica employs da capo form, and despite the notoriety of this form within many contemporaneous vocal compositions, it is one of only three da capo arias in the entirety of the work. The da capo arias occur at the beginning of the oratorio, in the middle—Monica‘s second aria, at the beginning of Part Two, in which she pains over her son‘s life, and in the final aria in which Simpliciano urges all who dwell in similar soulful torment to convert in the example of Saint Augustine. The usage of the da capo form serves to dramatically emphasize the urgency of conversion, as the restatement of text with further ornamentation would have heightened the characters’ pleas. All other arias in the oratorio employ dal segno form in which the opening ritornello is omitted and a new orchestral transition occurs between B and A‘. Characters primarily interact via secco recitative and arias, with the choir reserved for intense dramatic passages that call for the redemption of the sinner, St. Augustine, at the end of Part One, and of humankind in Part Two. The choir offers a dramatic restatement in the Part One finale duo between Alipio and Monica, in which Monica desperately prays that her son‘s slow progression toward conversion has not been in vain. At the conclusion of Part Two, after Simpliciano sings an initial statement in aria form about the need for all to convert, the choir‘s apex within the drama takes place. Through sheer force of numbers, the chorus serves to solidify Simpliciano‘s message and to urge the listener to follow in Saint Augustine‘s example of conversion.

This oratorio offers a unique opportunity to pursue the performance practices of the mid-eighteenth century, especially ornamentation conventions, as well as the appropriate balance between voices and instruments. Hasse’s instrumentation in La conversione recalls Bach’s passions—the piece is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two violins, a viola, a cello, a bass, and keyboard. Unlike Bach, though, Hasse employs much simpler harmonies to avoid interference with the text. In adhering to the galant aesthetics of simplicity, Hasse keeps the texture of the piece relatively thin, usually employing strings and continuo as the only accompaniment to recitatives. The recitatives are often lengthy, but performance practices dictate that in order to create more interest in the vocal line, certain embellishments would likely have been added. One of the most basic ornaments would be to alter the penultimate syllable a step above the written pitch to anticipate a cadence that occurs on the final syllable.Hasse employs typically Italianate string and continuo accompaniment during arias and occasionally creates a dialogue between the singer and one or two instruments. For instance, Monica’s first aria contains an alternation and later unification of florid, embellished melismatic passages between her vocal line and the first flute part. Hasse saves thicker orchestral textures for when the singer rests, as to avoid obscuring the vocal line and text declamation. Finally, choruses that end acts often contain colla parte, literally “with the part,” in which instruments sound as vocal lines, particularly with the chorus, but sometimes with the soloists. Care should be taken in the performance of this piece to ensure that these lines are balanced and that any musical shaping agrees among like parts.

Tucker Bilodeau, Michael McGee, and Ryan Wardell, 2016

For performance material please contact Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 132 |