Kongen op.19, Third Suite Op. 19

Halvorsen, Johan

23,00 €

Preface

Johan Halvorsen

Kongen

Third Suite, Op. 19

(b. Drammen, 15 March 1864 – d. Oslo, 4 Dec 1935)

Outside of Scandinavia, not much is known of Norwegian music or drama except for Grieg and Ibsen. Indeed, a vigorous musical culture before the middle years of the nineteenth century was largely confined to folk music. From the 1850s, middle-class musicians, aware of their insularity, looked toward Germany and its rich tradition of romantic music, and many went there to study. Inversely, as a result of growing Norwegian nationalism, these German-trained composers realized that elements from the rich vein of their native ethnic music could be incorporated into the Romanticism they had learned from their southern neighbors to create a distinctively Nordic musical genre. The four most prominent of the Leipzig-trained composers were Svendsen, Grieg, Sinding, and Halvorsen. They became a close-knit brotherhood, offering mutual support and encouragement.

Halvorsen, the youngest of the group, was born in Drammen, a town about 20 miles west of Christiania (Oslo). Displaying musical talent from a young age, he learned to play the violin, flute, cornet, and other brass instruments and to join the local band and various ensembles organized by Christian Jehnigen, a German immigrant. At the age of 15 he moved to Christiania to enlist in the brigade band, presumably to train as a military bandsman. He soon realized that in that environment there was limited scope for violin playing, which was his first love. After only a year he resigned and, for the next four years, he played in the pit orchestra of the Christiania Folktheater whilst pursuing his violin studies with a local teacher, Gadbrand Bøhn. A successful solo recital in his hometown in 1882 encouraged him to spend a year at the Music Conservatory in Stockholm, taking violin lessons from Albert Lindberg. He was then appointed leader of the Orchestra Harmonien in Bergen, but in less than a twelvemonth he had so impressed the music lovers of that city that they raised a subscription to allow him to pursue more study abroad. This was the start of several years travelling in search of teaching and performing opportunities and further study. He went first to Leipzig to study under the eminent violin teacher Adolf Brodsky. Then stopovers in Aberdeen, Helsinki, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Liège followed, including stints with the eminent violin pedagogues Leopold Auer and César Thomson. Although he had attained a high degree of virtuosity on his instrument, it was during his stay in Helsinki that the lively musical culture there led him to composing and conducting. These were to become the primary occupations for the remainder of his life, in which he was virtually self-taught. Returning to Norway, his first appointment (1893) was to Bergen to become Director of Music at Den Nationale Scene and conductor of the Orchestra Harmonien. He achieved a resounding success with his Bojarernes intogsmarsch (Entry March of the Boyars), which remains his most frequently performed work, especially in its transcription for band. Still performing and teaching violin, he wrote Pasacaglia on a Theme of Handel, a duo for violin and viola for himself and a colleague to play, that has also remained in the repertory. Yet so proficient had his conducting become that, on performing his suite from Vansatesena with the visiting Concertgebouw Orchestra at the Bergen Festival in 1898, his colleague, Johan Svendsen, declared; “You are a Maestro!” As successful and popular as were his years in Bergen, it was to be expected that he should progress to become the music director for the New National Theater in Christiania, the nation’s capital, where the distinguished playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson was theatre manager. The theater boasted the largest professional symphony orchestra in Norway consisting of 43 players. They played incidental music and entr’actes six nights a week. The responsibility for providing much of this now fell to Halvorsen’s pen. In addition, he gave frequent orchestral concerts and produced two operas annually. In a hectic schedule of up to 300 performances a year, it is not surprising that he recycled a number of his theatre scores as suites suitable for concert use. The present score consists of three movements from the incidental music he wrote for Bjørnson’s play Kongen, which received its premiere production in 1902.

The play Kongen (The King) was written in 1877 shortly upon Bjørnson’s return to Norway after a three-year absence spent in southern Europe. It was the third of three plays (the first two written in Florence and Rome, respectively) that demonstrate his determination to write more realistic dramas. Considered primarily a playwright, he had built his reputation with poetry and short stories of Norwegian peasant life, as well as plays on historical themes. His recuperative exile had recharged his creative faculties dulled by almost a decade immersed in theatrical management and periodical editing. These three works represent the working out in dramatic terms of the social philosophy of Bjørnson’s friend, the eminent Danish critic, Georg Brandes, as well as many of the radical writers and thinkers beyond Scandinavia that he had read voraciously during his sabbatical. The first two plays represent an attempt to depict a higher standard of truth in the worlds of journalism and finance. Kongen asks what role, if any, hereditary monarchy should play in the modern state. Can constitutional monarchy work as a viable alternative to republicanism? The play, in four acts and a prologue, approaches this conundrum from the monarch’s point of view by placing him at the center of the action. As well as social philosophy, it incorporates such diverse elements as comedy, romance, melodrama, and tragedy. In addition, the author wrote curiously poetic interludes (mellemspils) of a cryptic nature seemingly at odds with the actuality of the drama itself. Although the play was widely read and discussed after its publication in 1877, it is not surprising, in view of its complexity, that it had to wait 26 years for its first stage presentation in 1902. For this premiere Halvorsen wrote an extensive amount of incidental music, of which 10 separate items were used for this production. Even then it did not prove an unqualified success.

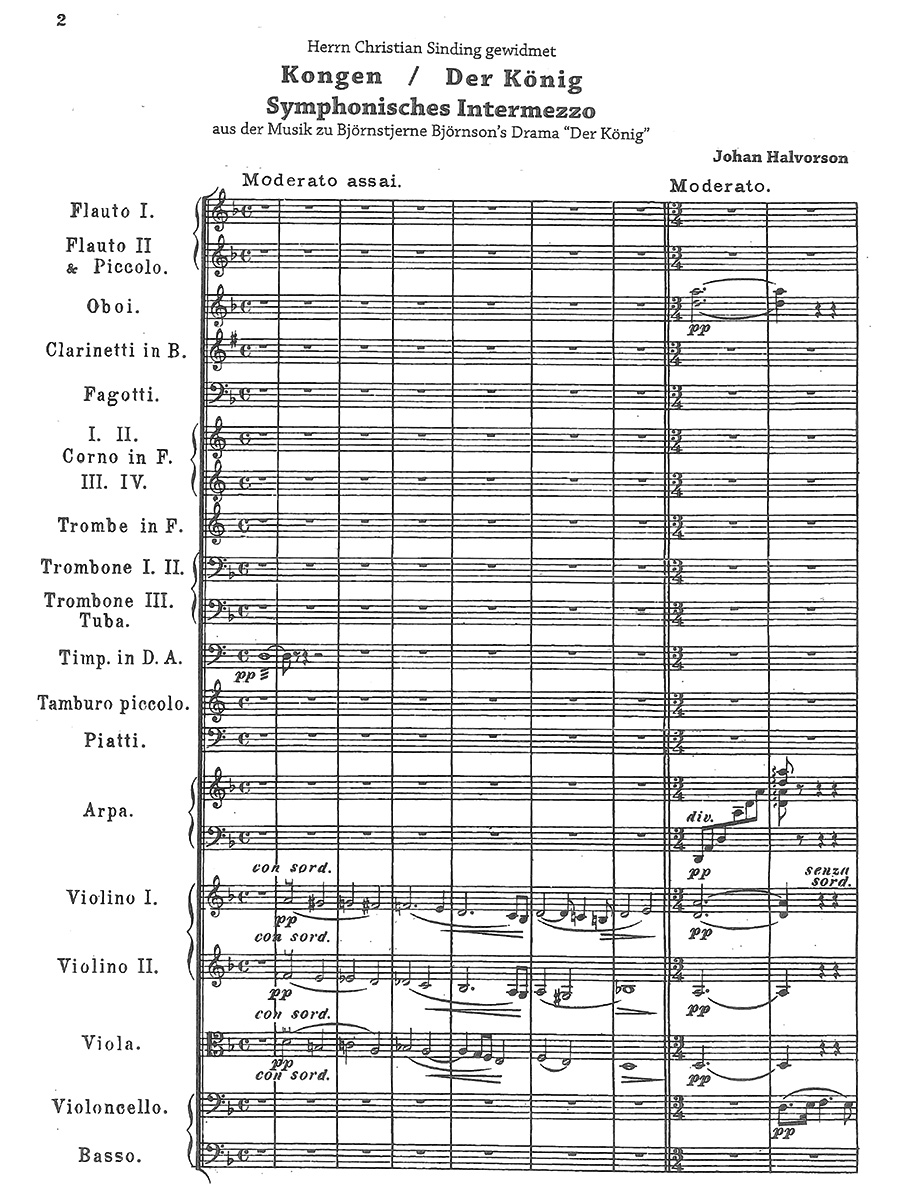

1. Symfonisk Intermezzo

This piece, the Entr’acte to Act II, was written to replace the original dramatic interlude which had proved too impractical to stage. In the play, about a third of the way through Act II, the King is heard to remark: “I was only deadening my thoughts by gossiping. My anxiety was too much for me.” We learn that the king has fallen in love with a middle class girl (Clara) whose father happens to be his severest critic. Up until this time she has spurned him (as was shown in the Prologue where she dismisses his advances with “I despise you.”). Now the King has arranged another encounter where he hopes to win her over, which is the cause of his extreme anxiety. This, and the image he has of her in his imagination, are the two elements, we suppose, seized upon by Halvorsen to be expressed musically. In view of the intensity of emotion suggested by the scene, it is perhaps not surprising that the composer chose to express himself, consciously or not, in Wagnerian terms. Much of the score conjures up reminiscences of Tristan und Isolde. The opening measures, a chromatically-descending passage on muted strings, sets up a mood of foreboding in preparing the serious key of D minor. Then follows an extended theme made up of four distinct phrases played by unaccompanied cellos. The bareness of the line allows us to appreciate the contours of the melody and its expressive intervals. The closing phrase is reinforced by violas, and a turn figure by the second violins at the cadence prepares for the theme’s repetition. It is immediately taken up by the violins with an oboe counter-melody and harmonized with light accompaniment from the woodwinds. Using elements of this theme, the music gradually builds up to a frenzied climax of four fortissimo diminished chords interspersed with a short overlapping Tristanesque descending figure and turn of great intensity. It would perhaps not be too fanciful to label this the “Clara love-theme.” As the music subsides, this love-theme is heard tenderly but quickly becomes more agitated and breaks off abruptly. The music begins to build for a third time displaying Halvorsen’s skill as an orchestrator by constantly varying texture and timbre. At the climax we hear the opening theme heralded by horns and trumpet and then by the trombones, until, finally, the climax is reached in D major. Then the music quickly subsides to usher in a repeat of the opening chord progression followed by a fragment of the main theme on solo cello to bring the movement to a close.

Hyrdepigernes Dans (Dance of the Shepherdesses)

The Prologue to the play opens in “A large gothic hall, brilliantly illuminated, in which a masked ball is taking place. At the rise of the curtain a ballet is being performed in the center of the hall. Masked dancers are grouped around watching it.” This is the music for that ballet. It shows the composer at his lightest and most trippingly cosmopolitan. It is in essence a Gavotte and Musette, a tripartite design, ABA, much favored in the French baroque suite and deriving from the pastoral entertainments popular at the French court. The former consists of two contrasting themes and the latter employs a drone bass. This reference to regal entertainment helps to reinforce the notion of hereditary monarchy that is one of the primary elements of tension in the play.

Elegi

As has been observed earlier, Bjørnson’s play encompasses a number of disparate, one could almost say incongruous, elements. The abrupt melodramatic ending to Act III where the heroine, Clara, drops dead at the sight of her father’s ghost is stretching credulity to the limit. Clearly, the playwright needs her death in order to set up the denouement of the fourth act. However, the situation gave Halvorsen the opportunity to provide an elegy of great tenderness and beauty. In a similar way to the first movement, it shows the composer’s ability to compose an extended composition using very sparse means, in this instance by providing what amounts to a set of variations on the brief opening motif: a descending and rising figure with an appoggiatura closing on dominant harmony and using the technique of overlapping it between voices. A similar, more wistful, theme is introduced by flutes and clarinet molto tranquillo, but this soon becomes fragmented and the music more agitated, emphasized by an interrupted cadence. After the first theme again expresses the intensity of grief, a succession of sighing descending fourths seems to express resignation leading into a quiet coda.

The pathétique nature of the two outer movements of the Kongen Suite encourages Halvorsen’s romantic bent. We can sense the influence of Liszt and Tchaikovsky, as well as Wagner–there is no need of Nordic folk elements here. Halvorsen is a master at catching the mood and psychology of the characters and situations he is attempting to portray. We marvel at this autodidact’s mastery of orchestration until we remember his hours of practical experience spent in conducting and composing. He is judicious in choosing only the best excerpts from all of the play’s music for inclusion into the suite. The present score lasts barely 15 minutes. On hearing the music, Bjørnson declared that he would not sanction performances of the play without Halvorsen’s music. A stop in Bergen on tour with his orchestra in the summer of 1903 at which Halvorsen programmed the Kongen Suite prompted Grieg to express his admiration saying: “His achievements are such that one can only regret that the whole of Europe could not be present to experience it.” A few years later, the composer is on record as saying that he considered Kongen to be the best music he had ever written.

Roderick L. Sharpe, 2016

For performance material please contact Hansen, Copenhagen.

Score Data

| Score No. | 1792 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Special Edition | |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Performance materials | |

| Piano reduction | |

| Specifics | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 76 |