Concerto No. 2 for Guitar and Strings, Op. 36

Giuliani, Mauro

23,00 €

Preface

Mauro Giuliani

Concerto No. 2 for Guitar and Strings, op. 36

(1812)

(b. Bisceglie, Province of Bari, 27 July 1781 – d. Naples, 8 May 1829)

Preface

Mauro Giuliani was born in the Apulian village of Bisceglie in southern Italy in 1781 and grew up only fifteen miles away in Barletta. Both villages, situated on the Adriatic coast, offered little by way of musical stimulation. Still, Barletta had a theater and an auditorium where operas were performed and concerts took place. Giuliani learned to play the cello and the guitar, and in 1803 he gave a concert in Triest, over six-hundred miles away from his native town on the present-day border to Slovenia. Here he played three works: a concerto for thirty-string guitar-harp, followed by a cello concerto and, after an intermission, by a concerto for the recently developed six-string guitar. Two things about this concert are especially interesting: first, Giuliani presented himself not only as a guitarist, by which he is known today, but also as a cellist; and second, he must have composed two solo concertos for guitar and another for cello by the age of twenty-two.

In 1806 Giuliani moved to Vienna in the hope of finding better opportunities for his artistic development. Only one year later he published his first compositions there and drew praise as a guitarist, as we know from a review in the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung: “Among the very many players of the guitar here, a certain Giuliani has garnered much success, and even great acclaim, with his compositions for this instrument and his playing. He truly handles the guitar with rare grace, dexterity, and power.” He remained in Vienna until 1819, composing his works up to op. 104. In 1810 the same Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung called him “perhaps one of the greatest living virtuosos on the guitar.” He gave concerts with Ignaz Moscheles and Louis Spohr, was personally acquainted with Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Ludwig van Beethoven, and played cello (or timpani) at the première of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony in 1813. In the late 1810s, as the Viennese public began to lose interest in the guitar and wished above all to hear piano music, Giuliani’s income from his concerts and lessons was drastically curtailed, and he lost contact with Vienna’s wealthy families. He therefore left Vienna in 1819 and returned via Prague to Italy. After traveling through various cities in northern Italy, he lived for a while in Rome, where he published the first three of his six Rossiniane for solo guitar (opp. 119–21). Based on themes from operas by Gioachino Rossini, they number today among his most popular works. In 1823 he relocated to Naples, where he died six years later.

In 1926 Fritz Buek, in Die Gitarre und ihre Meister, accurately described the general stylistic features of Giuliani’s music, even though he wrongly assumed that Giuliani was a violinist rather than a cellist:

“Giuliani’s style reveals many personal traits; he has a distinctive flowing melodic line that frequently escalates to orchestral effect, although he does not always incline to use counterpoint. One notices that he comes from the violin and cannot deny his origins. His technique and fingering are thus more attuned to melody than to harmony, that is, he has transferred many features of the violin to the guitar in his technique. But he enriches the guitar with a great many new effects and has created all his works from the essence of the guitar, so that nothing seems imposed upon it.”

As far as we know today, Giuliani produced some 150 compositions with opus numbers and another seventy without, all exclusively for or with the guitar. Among them are three solo concertos: No. 1, op. 30 (premièred in 1808, published in 1810); No. 2, op. 36 (1812); and No. 3, op. 70 (ca. 1823). Of these, the first is mainly played today. He also planned to write a fourth concerto as his op. 129 (1827) and sent its opening movement to his publisher in 1828, but it never appeared in print and has since vanished. Two early concertos of 1803 are likewise lost and were never mentioned later by the composer, who called op. 36 his Second Grand Concerto, thereby letting op. 30 mark the first in his series of his guitar concertos.

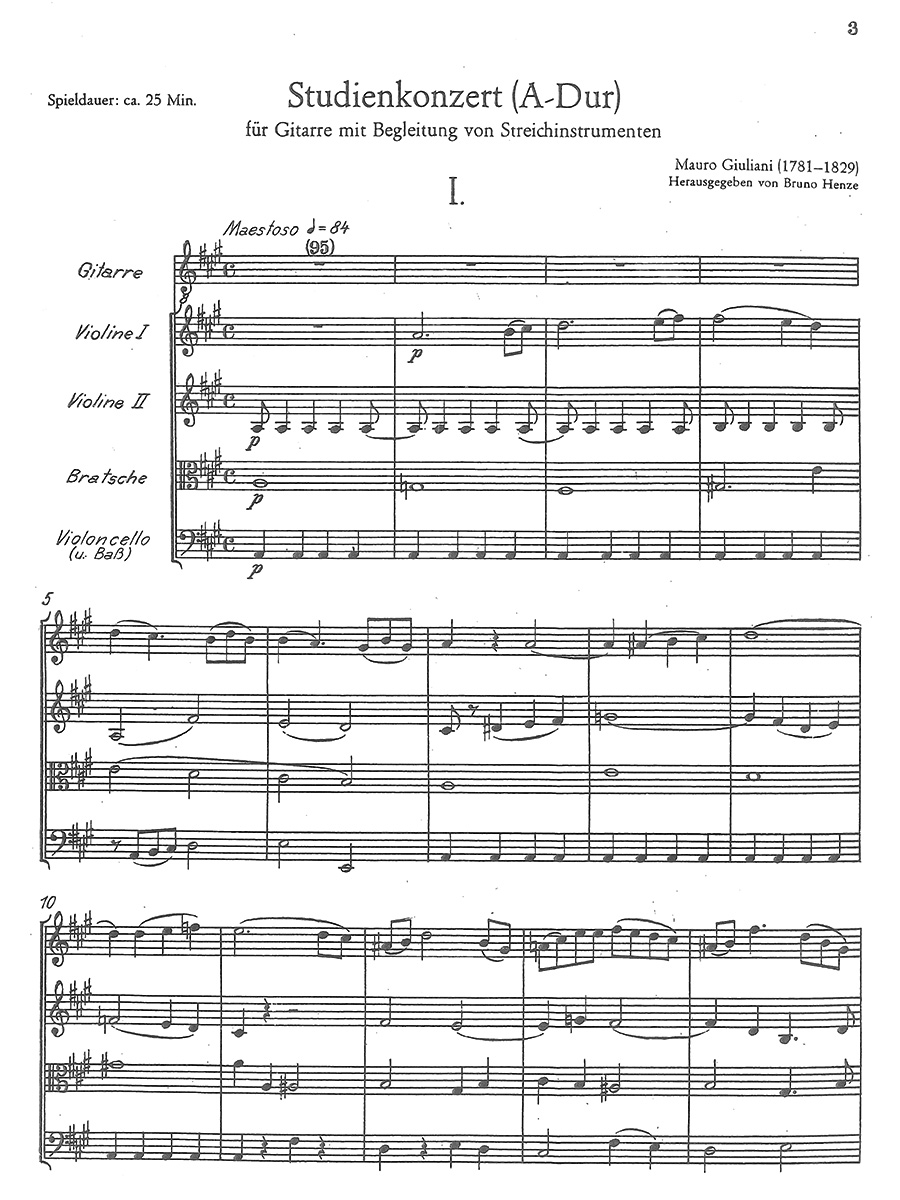

Concerto No. 2 survives in two different versions. One, published in 1812, is for the “normal” guitar (Primgitarre) with accompaniment “for two violins, viola, and cello.” However, the cello part also contains a part for double bass, so that the orchestra may rightly be called “with strings.” This is the scoring that appears in our volume, edited by guitarist Bruno Henze in 1959. (Another edition was published in 1973 by the Italian guitarist Ruggero Chiesa.) Around 1823 Giuliani wrote an alternative version for Terzgitarre, a slightly smaller instrument tuned a third higher. This version was also published around 1823, but only in a piano reduction. The scoring for Terzgitarre was also intended to be an alternative for his Guitar Concerto No. 1, and Concerto No. 3 is even written solely for this instrument.

Giuliani’s three guitar concertos mark the largest body of music for this combination of instruments in the entirely nineteenth century. (In 1799 the Spanish composer Fernando Ferandiere created a catalogue of his works listing six concertos for guitar, but they have disappeared without a trace.) His Second Concerto, in A major (a key easily negotiated by guitarists) is laid out in three movements, with a fast opening movement, a calm second movement, and a fast rondo-finale. The first movement is impossible to grasp in terms of the sonata-allegro form that Giuliani employed in his First Concerto. Thomas F. Heck (1995, Appendix II–B) divides it into a double exposition (orchestra in mm. 1–95, soloist in mm. 96–202, orchestral conclusion in mm. 202–43), a development section (mm. 243–322), and a recapitulation (mm. 323–84), but these formal sections do not meet our normal expectations. First of all, the guitarist’s exposition does not repeat the material set down by the orchestra. In the final analysis there is one clearly recognizable main theme, two-thirds of which are stated in each of the two expositions (mm. 49–69 and 149–64). The development begins with a new theme. Only then does the main theme reappear in varied form (mm. 279–87), clearly set apart by a modulation to C major. The recapitulation, again in A major, opens with the variant from the development section (mm. 323–38). Between these four eight- to sixteen-bar thematic statements, the first theme from the development section, and a few thematic areas that do not coalesce into self-contained themes (e.g. mm. 1–15, 33–49, and 136–42), the soloist plays brilliantly virtuosic passages. The important entrances at the openings of the solo exposition and the development section are prepared with fairly long passages of calm and gentle music for the strings. One does greater justice to this concerto by not measuring it against the yardstick of sonata-allegro form and viewing it as a largely free-form fantasy.

The second movement, a tranquil Andantino, is based on a lyrical theme stated first by the strings (mm. 1–8) and then repeated and varied by the soloist (mm. 9–20). There follows a more dramatic section with subdued virtuosity from the soloist (to m. 33), after which the strings play a theme derived from the opening to ease the dramatic tension. The next section enlarges the harmonic spectrum in placid broken triads and octave runs from the guitarist. At the end (m. 52) we again hear the opening theme, which tapers off in subdued virtuosity, as in the first section. Here Giuliani has created a well-proportioned and expressive miniature.

The finale is a rondo in seven richly contrasting sections, each of roughly equal duration: A (mm. 1–58), B (mm. 59–92), C (mm. 93–167), A (mm. 167–94), D (mm. 195–246 with guitar accompaniment), C (mm. 247–301), and A (mm. 301–38). Combining the episodes, we arrive at the following form: A – B+C – A – D+C – A, or, rewritten more simply, A–B–A–C–A, where the episodes are divided in two and differ only in their first subsection. Again to quote Fritz Buek: “These three concertos, of which the second must be called the most beautiful, are among the most substantial and significant works of the classical guitar repertoire. They draw on Haydn and Mozart for their form and style and are written for the Terzgitarre, accompanied by a string quartet or small orchestra.”

Translation: Bradford Robinson

Bibliography

Buek, Fritz, Die Gitarre und ihre Meister (Berlin, 1926).

Ferrari, Romolo, “Mauro Giuliani: Eine Lebensbeschreibung mit Anmerkungen,” Der Gitarrefreund 30 (1929), nos. 11-12, pp. 81–85; vol. 31 (1930), nos. 1-2, pp. 100–02, nos. 3-4, pp. 113–16, nos. 5-6, pp. 129–31, nos. 7-8, pp. 145–47, and nos. 9-10, pp. 161–67.

Riboni, Marco, “Mauro Giuliani: un aggiornamento biografico,” Il Fronimo, no. 81 (1992), pp. 41–60; no. 82 (1993), pp. 33–51; Ger. trans. as “Mauro Giuliani: eine biographische Aktualisierung,” Gitarre & Laute 15 (1993), no. 4, pp. 18–22 and 25–27, no. 5, pp. 17–22, no. 6, pp. 59–66; vol. 16 (1994), no. 1, pp. 49–54.

Heck, Thomas F., Mauro Giuliani: Virtuoso Guitarist and Composer (Columbus, Ohio, 1995).

Heck, Thomas F., “Mauro Giuliani,” in Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London, 22001), vol. 9, pp. 910–11.

Penn, Gerhard, Mauro Giuliani und andere Gitarristen in München – Übersehene Fakten und verschollene Werke, http://www.gitarre-archiv.at/dateien/Penn-Giuiliani-und-Mu%CC%88nchen-Kopie.pdf (2014).

Lorenz, Michael, New Light on Mauro Giuliani’s Vienna Years, http://michaelorenz.blogspot.co.at/2015/04/new-light-on-mauro-giulianis-vienna.html (accessed on 11 April 2015).

Aufführungsmaterial ist von Hofmeister, Leipzig, zu beziehen. Nachdruck eines Exemplars der Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, München.

Score Data

| Score No. | 1779 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Special Edition | |

| Genre | Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Performance materials | |

| Piano reduction | |

| Specifics | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 78 |