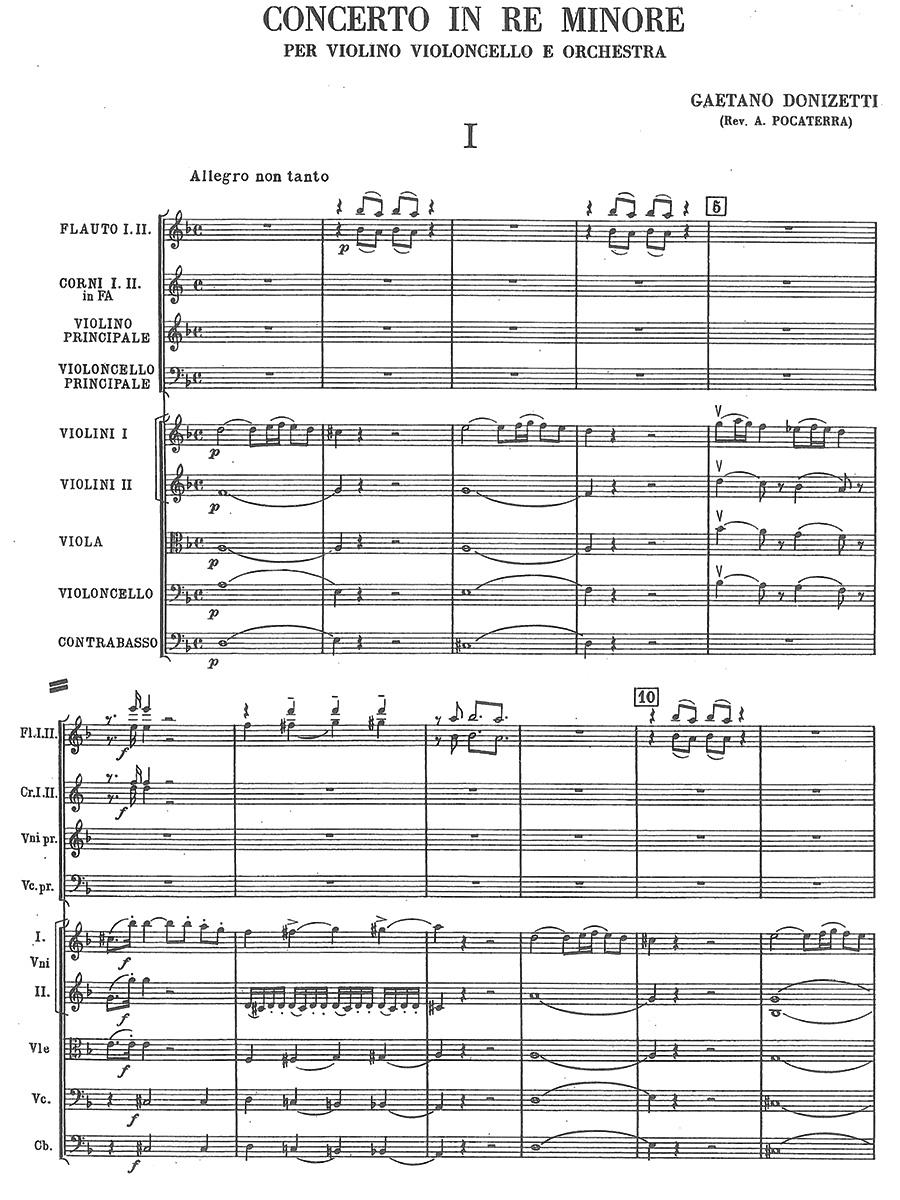

Concerto in Re Minore

Donizetti, Gaetano

16,00 €

Preface

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti

Concerto in Re Minore

(Double) Concerto in D minor for violin, cello, and chamber orchestra

(b. 29 November 1797, Bergamo

I. Allegro non tanto (6.5-7 minutes) p.1

II. Andante (1.5-3 minutes) p.13

III. Rondo: Allegro moderato (3 minutes) p.15

Orchestration

solo violin, solo cello, 2 flutes, 2 trumpets, chamber strings

Publication

Bergamo period, date of composition unknown

Reconstructed by Johannes Wojciechowski for Edition Peters

Donizetti’s Concerto in D minor for violin, cello and chamber orchestra is derived from the autograph

preserved in the Paris Bibliothèque Nationale (reg. no. Ms. 4142). The dating of the work is not clear,

but its general layout suggests that it belongs rather to the early Bergamo period

than the later period in Paris.

Donizetti

The composer was born into poverty in Bergamo (occupied by the French and then the Austrians for Donizetti’s entire life), but he and his brothers were invited to attend the best free music school in Italy, run in Bergamo by Giovanni (Johann Simon) Mayr. In his teens, Gaetano was sponsored by Mayr in order to study for two years in Bologna with Padre Mattei, and his teachers began to hand over contracts to him by age twenty. Gaetano’s brother Giuseppe became the Sultan’s maestro di cappella In Istanbul, and both developed into handsome, tall men with curly dark chestnut hair. In addition to dozens of operas, Gaetano composed over three hundred pieces of orchestral and chamber music and roughly 250 songs, many in Neapolitan dialect. The wife of La Scala’s main librettist Felice Romani described Gaetano as “likeable beyond all description: the fair sex went mad for him.”

Verdi was a great admirer of Donizetti, and vice versa: Verdi’s second wife Giuseppina Strepponi sang L’elisir twice and Donizetti helped supervise rehearsals for one of Verdi’s early operas. The young Verdi wrote to Donizetti: “You belong in the small number of men who have sovereign genius and need no individual praise.” Donizetti responded publicly, “My heyday is over, and another must take my place. I am happy to give mine to people of talent like Verdi.” As the age of bel canto drew to a close, Donizetti continued to employ melody in order to communicate the emotions of the characters, but in Donizetti’s later works, you can hear the darkness, turbulence, and intensity that became typical of Verdi.

Music

Donizetti wrote more than half of his sixty operas for Naples, but eventually moved to Vienna and then Paris. A contemporary of Rossini (who retired early) and Bellini (who died tragically young), he wrote quickly, remarking, “Rossini wrote The Barber of Seville in thirteen days? Ah! He always was a lazy fellow!” French composer Adolphe Adam summed up the typical reaction to the vibrant composer: “It was impossible to be near him without loving him.”

Throughout his career, Donizetti referred to “writing” or “composing” when creating a piano/vocal score, and he often made revisions and adjustments before finally orchestrating an opera or instrumental work: when he announced that he could write an opera in ten days, he was excluding the time for orchestration, editing, the creation of parts (which he usually made himself), and copies of the full or short score.

Composers were expected to conduct the first three performances of a new opera, and if the show survived, a house conductor (usually one of the strings) took over. Opera orchestras contained a few instrumental virtuosi, but some instruments did not yet reach their modern, fully brilliant sounds during Donizetti’s lifetime (notably, the bass viol, trumpet, bassoon, and French horn).

Donizetti’s fame almost entirely rests on operatic works first produced in the period 1832-1835 (L’elisir d’amore, Lucrezia Borgia, Maria Stuarda, and Lucia di Lammermoor). Earlier in his career he wrote for the piano, chamber music (including at least seventeen string quartets) and sacred works. His output includes a few instrumental concertinos written when he was about twenty: all were left incomplete except a concertino for English horn.

His instrumental music developed from the vocal writing of the time: leading themes are essentially streams of melody, sufficiently varied to sustain interest and floating above the rest of the orchestral texture. The most ambitious work, and the longest at eleven and a half minutes, is his three-movement double concerto for violin and cello, with important wind parts, notably for the flute.

Double Concertos

Donizetti’s double concerto is traditionally structured in three movements, but the use of two strings instruments as soloists was revolutionary in romantic music at the time. Donizetti’s hastily written manuscript, extending to forty-four pages, had been in the private collection of one of the world’s best known collectors, Charles Malherbe, subsequently archivist at the Paris Opéra. The manuscript cost him, as the first page of the score reveals, the sum of 30 francs and 60 centimes.

This concerto for violin, cello, and orchestra, often called the Double Concerto, has a typical small Classical orchestra of strings and winds and is a throwback to the old sinfonia concertante tradition. It is characteristically melodic and, in its slow movement, easy to mistake for a romantic operatic duet sans text.

Examples of earlier works featuring the same two soloists include:

Six double concertos by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741, Venice) RV 544, 546-47; op. 20, no. 2; PV 238; PV 308: only one of these was published in the composer’s lifetime

Symphonies Concertantes in A (C. 79) and B-flat (C. 46) by Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782,

“the English Bach”)

Concerto in G Major for violin, cello, and strings (Badley VII:G1) by Leopold Hofmann

(1738-1793, Kapellmeister of the Vienna Cathedral during Mozart’s lifetime)

Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat, K. 364 (1779),

arranged from the original for violin, viola, and orchestra

Sinfonia Concertante in D Major by Carl Stamitz (1745-1801,

eldest son of the Johann Stamitz, leader of the Mannheim Orchestra)

Concerto for violin and cello by Antonín Vranicky (1761-1820)

During the late romantic and modern eras the double concerto became popular, with orchestral works featuring violin and cello soloists by Kurt Atterberg (1960), Johannes Brahms (1887), Richard Danielpour (2000), Frederick Delius (1916), Mohammed Fairouz (2010), Philip Glass (2010), Lou Harrison (for violin, cello, and gamelan, 1982), James Horner (2014), Ezra Laderman (1986), Julius Röntgen (1927), Miklós Rózsa (1958), Camille Sant-Saëns (1910), Alfred Schnittke (1982), Roger Sessions (1971), and Eugène Ysaÿe (1927).

References

James Cassaro’s Donizetti: A Guide to Research (2000) provides a survey of easily available primary and secondary sources, including more than a dozen collections of letters and chapters on reviews and catalogs of the composer’s works. William Ashbrook’s Donizetti (1965) and his detailed Donizetti and his Operas (1982) together form the most thorough biography of the composer’s life and works. The two most important collections of Donizetti’s musical manuscripts, letters, and personal ephemera are the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, France and the Museo Donizettiano in Bergamo, Italy.

©2015 Laura Stanfield Prichard

San Francisco Opera and Symphony, Chicago Symphony

For performance material please contact Schott, Mainz.

Score Data

| Score No. | 1686 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Special Edition | |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Performance materials | |

| Piano reduction | |

| Specifics | |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 34 |