Requiem

Delius, Frederick

21,00 €

Preface

Frederick Delius – Requiem

(b. Bradford, Yorkshire, England, 29 January 1862 — d. Grez-sur-Loing, France, 10 June 1934)

Delius chose to live for most of his creative life in relative seclusion in rural France, removed from the hurly-burly of urban life where most artistic activity takes place. Perhaps this self-imposed separation goes some way to explain the nature of his ‘pagan’ Requiem and why it received such a hostile reception at its premiere in London on 23 March 1922. Only someone so far removed from the tenor of the age could imagine that such a work with such a title would not be offensive at a time when the ravages of the First World War were still being felt and when conventional religious belief was of some comfort to the many bereaved and disillusioned. And just as the non-traditional text was excoriated, so the music was thought to be inferior, and, despite receiving a much more favorable response at the German premiere in Frankfurt several weeks later, the work was not performed again anywhere for almost thirty years.

It is clear from reading Delius’s letters that he was not as unworldly as is often supposed. In the years before the First World War, he kept a close ear on what was happening in the musical world of his time. He traveled extensively in Europe to attend performances of his own and others’ music, and was in constant touch with publishers, performers, and friends to propagate his music. One suspects that with the Requiem he knew precisely what he was doing. It is well-documented that Delius could be deliberately confrontational and tactless. The choice of the title is in itself provocative. Delius presents his listeners with a challenge – a paean to the pantheistic and rational point of view regarding death.

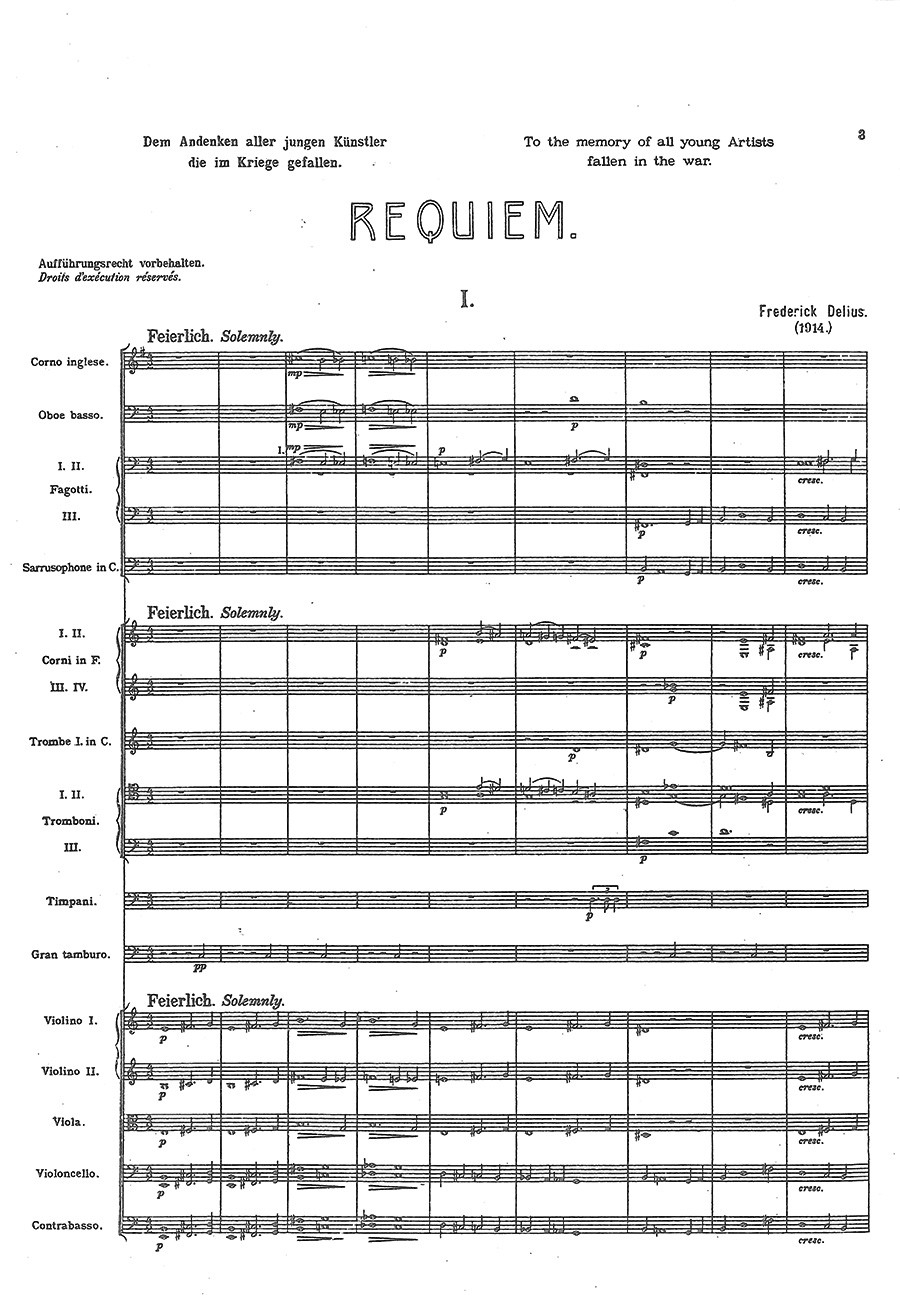

The Requiem is complementary to Delius’s earlier large-scale choral work A Mass of Life (1904-05). Together they address what he considered to be the essential questions of existence. The Mass is a poetic affirmation of life as Nietzsche expressed it, in carefully chosen excerpts from his prose-poem Thus Spake Zarathustra, and while mortality is hinted at there, Delius evidently felt the need to deal with the primary issue of non-existence much more forcibly and unequivocally. It is his manifesto of death and thus he felt justified calling this companion to the Mass a Requiem. Some have wondered if this work was Delius’s response to futile loss of life in the Great War – a view strengthened by the dedication “To the memory of all young Artists fallen in the war,” appended in 1916. The chronological evidence would tend to discount this notion, because Delius was already at work on the Requiem in the Fall of 1913. He had his text by then and may have been contemplating a work along these lines for several years previously. On the other hand, although the bulk of the composition seems to have been completed by 1914, he continued to work on the score for the next two years, and it is conceivable that some of his wartime experiences had an effect. He makes clear what he is about in a program note prepared for the first performance where he states: “It is not a religious work” (although, in a sense, it really is!). We see the influence of Nietzsche’s ideas in phrases like “the Reality of Life” and “great laws of all-being.” The composer tells us (not very tactfully) that it is the weakling who seeks solace in the myth of a Hereafter. Since death brings an end to consciousness, then “fulfillment can be sought and found only in Life itself,” and any morality or code of conduct must be imposed from within.

No one is given credit for the text either in the printed score or the manuscript. For many years it was assumed to be by Delius himself, and there can be little doubt that he had a hand in it. Delius’s protégé, Philip Heseltine, reported seeing the words in September, 1913, commenting that “The text is a wonderfully lovely prose-poem by a modern German poet,” but fails to name him. A contract with the publisher, Universal Edition, unearthed in the mid-1970s, indicates that the polymath, Heinrich Simon, sometime editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung and a friend of Delius, be accorded the primary responsibility, though how or when they agreed to a partnership is not known. As well as its Nietzschean tone, the text also paraphrases and adapts passages from Ecclesiastes. Delius never set text to which he was less than fully committed, so we can be sure he was heavily invested in this one despite its shortcomings. Heseltine made the English translation in 1919.

Delius’s score of the Requiem is laid out in five movements that are musically distinct, and the work may be considered in two main parts: the first (movements I & II) presents the challenge of “Reality”; the second (movements III, IV, & V) deals with the compensations and responsibilities of the lived-life, in which (especially in V) “harmony with Nature and the ever-recurrent sonorous rhythm of Birth and Death” are the vital elements. The structure of the work is primarily determined by the text, each phrase or stanza being treated with new musical material. Textural contrast is often achieved by alternating one or other of the soloists, then both, with the divided chorus. Except in a very few instances, Delius adopts a ‘call and response’ approach whereby the chorus echoes the words of the soloist. In movements I, II, and III there are elements of recapitulation when previously stated sections of text are repeated, and although the music is also reminiscent at first, it is never repeated verbatim – the recall takes on its own life, seeming to enrich the cohesion of the movement as a whole. What catches the listeners’ ears are the melodic motifs that populate each movement. The opening measures of the first movement, a somber funeral march of parallel fifths complete with muffled drum-beat, outline a minor third melodic cell, which, in various modifications, occurs throughout the movement. Another such is the signal rising triplet figure, a favorite Delius motif, first heard tentatively at measure 11. Taken as a whole, the movement is a careful blending of its austere backdrop interspersed with rhetorical passages from the baritone, contrasting sections of impressionistic coloration, and lush chromatic eight-part choral writing.

Before going on to discuss the remaining movements we must address the issue as to why the music was considered by early commentators to be inferior to Delius’s best work. The opening movement has an asperity that is unlike anything previously heard in the works of his maturity (1889-1910) but which is quite appropriate for a work about death – lack of belief in an afterlife doesn’t make the anticipation of death any less daunting! Anthony Payne, in his essay on the Requiem (“Delius’s Requiem”, in: Tempo, New Series, 76, Spring 1966: p. 12–17), argues that it is the composer’s response to an awareness that his ability to write constantly at his “nerve’s ends” was diminishing. The Requiem was an “ideal partner” for him to write music “geared to a more austere and consciously manufactured world.” In other words, it is a watershed work, and it is interesting to observe that what followed was a series of works in the more traditional forms: Concertos, Sonatas, and a String Quartet.

The opening of the second movement is the most pro-blematical passage in the entire work and must have struck the first listeners as positively bizarre. Delius clearly struggled to find a way to portray the futility of competing religious traditions. He had written to his friend, the critic Ernest Newman, for suggestions of musical themes to portray this idea in October of 1913. The composer’s solution, combining the texts “Hallelujah” and “La il Allah” with music that is bogged down in foursquare sequences, is not at all convincing. However, the movement quickly recovers in a restless piu lento for the baritone soloist. The triple-time section that follows is one of the most memorable melodically of the whole work, and is taken up most effectively by the chorus divided between those who repeat the text and those who vocalize “ahs” over a descending chromatic bass line. The succeeding section, a paraphrase of Ecclesiastes 9:7-10, is accompanied by lush strings, the vocal phrase ending with a characteristic rising tone.

The text of the third movement is an elaboration of Ecclesiastes 9:9: “Enjoy life with the woman you love.” The male soloist extols the virtues of woman’s love in metaphorical terms, likened to a flower. The music, consequently, is more rhapsodic than heard previously. Musically it is dominated by a rising triplet motif that occurs in two versions, one with a following descending dotted rhythm, the other falling away in a stepped figure. The fourth movement celebrates the ultimate challenge of the Übermensch to face death without fear, even alone. Although this is imagery we might be a little uncomfortable with today, the setting is wonderfully sensitive and expressive. The soprano soloist sings five phrases in long lyrical lines accompanied by orchestration of great delicacy, while the chorus has only three very brief but strategically placed responses.

The fifth movement is a remarkable instance of the nature portraits at which Delius so excelled, and is, by common consent, the most inspired portion of the work. The large instrumental and choral forces are employed in most imaginative ways. There are three main sections and a coda: the first contrasts the dormant atmosphere of the high peaks with the restive activity of early spring; the second portrays the stillness of the forest with the “eternal renewing” taking place all around; the third acknowledges all four seasons, but it is spring that receives the most rapturous expression. There is a brief stark passage of appoggiatura chords that dissolve into the blissful, unresolved coda and that may serve as a reminder of the reality of death for each individual. Just as in the first movement each day mirrors the life-cycle, so the passing seasons serve as a similar metaphor here. Delius expresses the restlessness of nature through extensive use of various ostinato figures; the principal melodic motifs are reminiscent of the folk tunes of his beloved Norway; and the delicate orchestration is enriched in parts by the use of harps, bells, and celesta. It is the renewal of life in springtime that makes sense of Delius’s vision of reality.

The Requiem received its American premiere at Carnegie Hall in New York City on 6 November 1950, which was almost certainly the first performance since 1922. However, it was a performance in Liverpool under Charles Groves on 9 November 1965, for which occasion Boosey & Hawkes published a miniature score, which is credited with rekindling serious interest in the work. Shortly thereafter the celebrated recording by conductor Meredith Davies with John Shirley Quirk and Heather Harper as soloists was issued. Another fine recording conducted by Richard Hickox was made in 1997. There have been occasional performances in the United Kingdom and America in recent years, but none, so far as is known, in Germany. Philosophically, it is probably the sexism of the text rather than its anti-religious sentiment that is likely to raise eyebrows today. But such a work of substance and beauty can stand on its own feet, and when heard with an unbiased ear can be appreciated in a way that makes sense of Delius’s own claim: “I do not think that I have ever done better than this.”

Roderick L. Sharpe, 2010

For performance material please contact Boosey & Hawkes, Berlin.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Pages | 64 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |