“Des Sängers Fluch” Op. 16 (Ballad for orchestra)

Bülow, Hans von

19,00 €

Hans von Bülow

(b. Dresden, 8 January 1830 – d. Cairo, 12 February 1894)

Des Sängers Fluch

Preface

Hans von Bülow led a remarkable life among the most famous characters of the late 19th century Romantic movement in German music. He was born in Dresden in 1830 and began his musical studies at the age of nine with Friedrich Wieck. In 1849 his parents demanded that he pursue a career in law, sending him to Leipzig where he met Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. He heard Wagner conduct in Dresden and attended the premiere of Lohengrin under Liszt’s baton at Weimar in 1850. By this time, a law career was far from his mind and on Wagner’s recommendation he acquired his first post as conductor in Zürich. The position in Zürich was shortlived, however, so he found a position at the small opera house in St. Gall, where he famously conducted Weber’s Der Freischütz without a score.

In 1851, he began studying piano with Liszt in Weimar where he also began to compose and write reviews. This was followed by a period of touring as a virtuoso through 1854. During this time his memorization and interpretation of all of Beethoven’s sonatas achieved the level of legend, leading even Hugo Wolf to state thirty years later that “Among virtuosos, he [Bülow] stands alone as an interpreter of classical music, especially of Beethoven’s keyboard works.” In 1855 Bülow accepted a position as teacher at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin. In 1857 he married Liszt’s daughter Cosima, and the couple visited Wagner in Zurich during their honeymoon. The next year he began working on a Keyboard reduction of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde—a work that is similar in many ways to Bülow’s own Nirwana (Op. 20). Overall, Bülow’s continuing support of the New German School was probably the reason Ludwig II saw fit to appoint him as court pianist, conductor and directory of the conservatory in Munich, where he conducted the premieres of both Tristan und Isolde (1865) and Die Meistersinger (1868).

The work contained in the present edition, Bülow’s Des Sängers Fluch (The Singer’s Curse), was premiered on New Year’s Day in 1863 under Bülow’s baton. It is an orchestral ballade after a poem by Ludwig Uhland (1815), which is itself based on a Scottish ballad published by Herder in his Volkslieder. Uhland’s ballad tells the story of a two medieval minstrels, one young, one old, who sing so well at a court that the courtiers stop their fighting and the Queen casts a rose from her breast to their feet. In a fit of jealous rage the King ruthlessly murders the young minstrel. The older minstrel then receives the body of his murdered friend and on his way out of the hall he curses the king. Overall, the poem’s medievalism, as well as its bloody content, are quite typical of poetic ballads from the romantic era.

Formally, the ballad is organized into 16 stanzas of four lines each with a rhyme scheme of aabb. The first two stanzas, for example, are:

Es stand in alten Zeiten ein Schloss, so hoch und hehr, Weit glänzt’ es über die Lande bis an das blaue Meer, Und rings von duft’gen Gärten ein blüthenreicher Kranz, Drin sprangen frische Brunnen in Regenbogenglanz.

Dort sass ein stolzer König, an Land und Siegen reich, Er sass auf seinem Throne so finster und so bleich;

Denn was er sinnt, ist Schrecken, und was er blickt, ist Wuth, Und was er spricht, ist Geissel, und was er schreibt, ist Blut.

The poem describes two primary worlds, the “dark and pale (“so finster und so bleich”) is contrasted with the shiny rainbow (Regenbogenglanz) in the world of the minstrels, with the narrative developing from a bright and positive beginning to the darker cursed world of the King. The curse itself reflects the minstrel’s specific power to control the way that history is told and remembered, with the ultimate result being that the King’s deeds and his family are forgotten (the last and most famous line reads: “Des Königs Name meldet kein Lied, kein Heldenbuch!/Versunken und vergessen! das ist des Sängers Fluch.”)

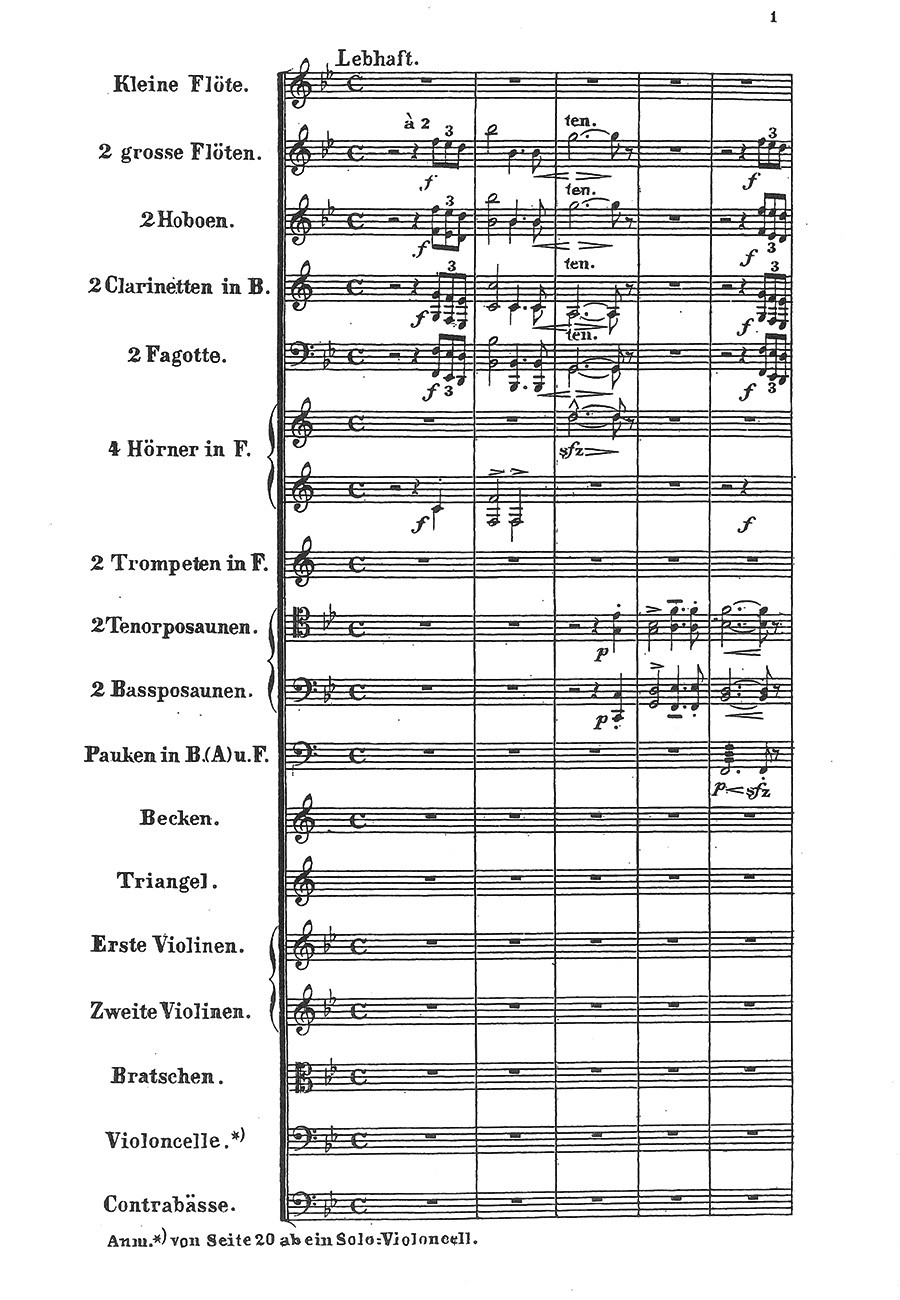

In setting this ballad, Bülow employed a Lisztian process of thematic transformation. The work opens in B-flat major with a grand and majestic theme (the Castle and court) which is soon contrasted by a dotted descending theme (the minstrels) which appears in a series of different contexts and transformations. Their actual song is given as a cello solo which shifts abruptly to B-flat minor at the King’s violent outburst. From here, in series of modal shifts, the grand theme of the opening is slowly liquidated in a musical manifestation of the minstrel’s curse. The minor key wins the day, when at the end of the piece the opening theme is all but forgotten.

Bülow’s context and familiarity with the work of other composers from the 19th century can be heard in many parts of this work. Odd instrumental pairings are reminiscent of Berlioz, who was long an idol for Bülow. The arpeggiating woodwinds in the minstrel’s curse seems inspired by Weber’s woodwinds from Oberon. Overall the process of thematic transformation and developing variation are well developed and seem to strongly anticipate some of Richard Strauss’s adult tone poems—Don Quixote in particular comes to mind.

Ultimately, Des Sängers Fluch is not well known as a musical expression of genius in the 19th century. In fact, its primary claim to fame is what happened miles away from the concert hall during rehearsals for its third performance on November 28, 1863. On this day, Wagner, on his way to conduct a concert in Löwenberg, stopped by to meet the Bülows in Berlin and to hear Hans conduct this piece that evening. As Hans was nervously rehearsing the piece at the concert hall, Cosima and Wagner went for a ride through the city and infamously declared their love for each other. Wagner would go to the concert that night, and spend the night at the Bülow’s before proceeding on the next day, only after complementing Hans on his music and conducting. Bülow was blindly cuckolded by his wife and Wagner through 1865, and one child, before he finally discovered the affair. Throughout the rest of the decade and until he received a divorce, he remained dedicated to performing Wagner’s music.

Joseph Morgan, 2013

For performance material, please contact Robert Lienau Musikverlag, Erzhausen.

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 60 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |