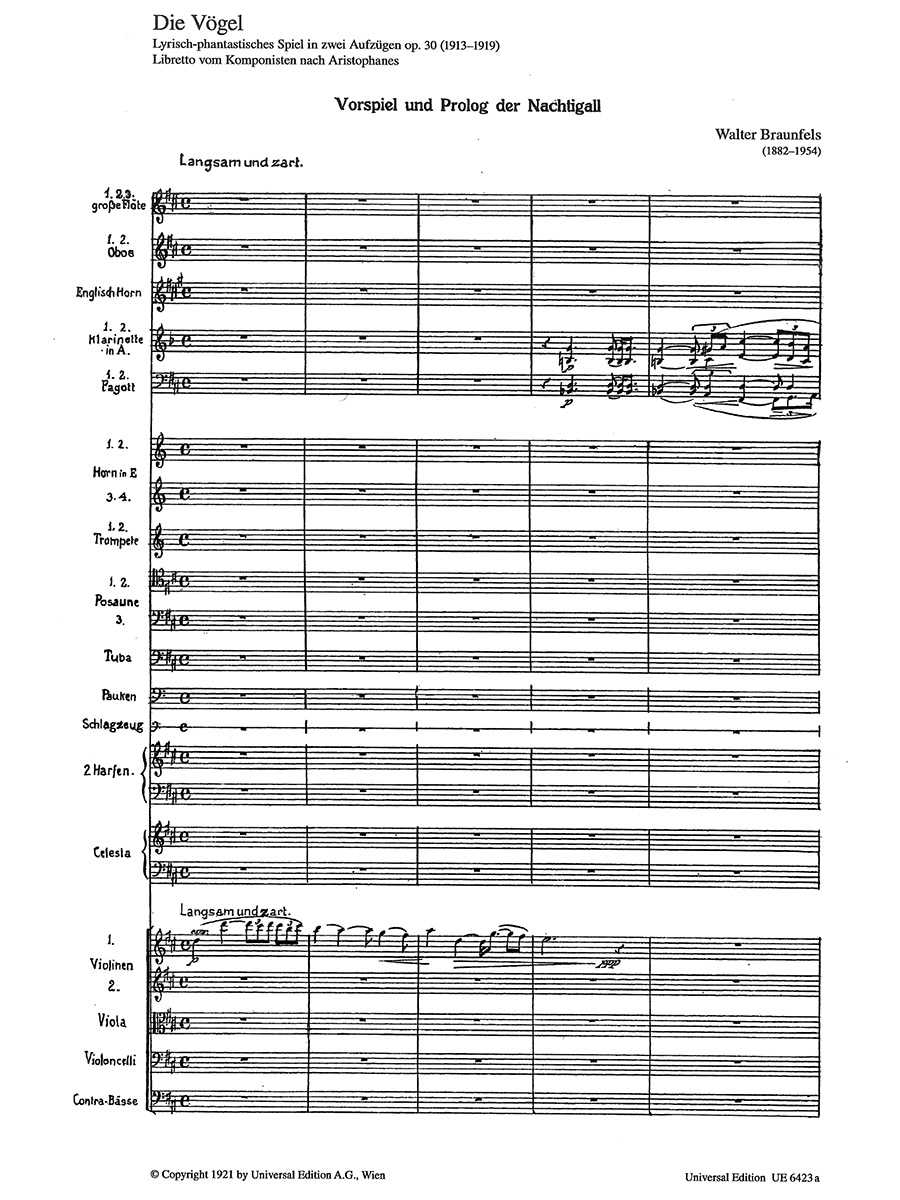

Die Vögel, Op. 30 (in two volumes with German libretto. First time available for sale)

Braunfels, Walter

72,00 €

Preface

Walter Braunfels

(b. Frankfurt, 19 December 1882; d. Cologne, 19 March 1954)

Die Vögel (The Birds), op. 30 (1913-19)

Lyrico-fantastical play in two acts

on a libretto freely adapted by the composer from Aristophanes

Preface

Walter Braunfels belongs to that group of German composers who were forced into “inner emigration” during the Third Reich. In 1933, at the height of his career, with several successful operas to his credit, he was summarily removed from his directorship at Cologne Musikhochschule and officially blacklisted throughout the Reich: performances of his music were prohibited, and his name was struck from publications. Half‑Jewish and vociferously out of sympathy with the new régime, he withdrew from public life and retired to the countryside, where he worked in isolation on his compositions. After the war Konrad Adenauer personally restored him to his former position in Cologne, where he helped to rebuild the Musikhochschule before retiring in 1950. He left behind a large body of music ranging from the brilliant comic operas and orchestral essays of his youth to the austere, mystical oratorios of his old age (Braunfels was a devout convert to Catholicism).

Today Braunfels is remembered mainly for his operas, most of them on librettos adapted by himself from literary models: Die Vögel after Aristophanes’ The Birds (1920), Princess Brambilla after E. T. A. Hoffmann (1908), and Don Gil von den grünen Hosen after Tirso de Molina (1924). Of these, Die Vögel is generally considered to be his masterpiece. Its long gestation (1913-19) is accounted for by the First World War, where Braunfels served on the Western front after being drafted in 1915. Wounded in action in 1917, he returned to his native Frankfurt, converted to Catholicism, and resumed his musical career as an accomplished pianist. Die Vögel was brought to completion in 1919 and premièred at the Munich Opera on 30 November 1920 with a star-studded cast (Maria Ivogün, Richard Strauss’s coloratura soprano of choice, sang The Nightingale, and the great tenor Karl Erb sang Hoffegut). The conductor that evening was none other than Bruno Walter, who in later life called Die Vögel

“the most interesting production of my Munich period. … Those who were privileged to hear Karl Erb’s song of man’s yearning and Maria Ivogün’s comforting voice of the nightingale from the tree-top, and those who were cheered by the work’s grotesque scenes and touched by its romantic ones, will surely remember with gratitude the poetic and ingenious transformation of Aristophanes’ comedy into an opera.” (Alfred Einstein, Theme and Variations, New York: Knopf, 1946, p. 236).

No less enthusiastic was the review by Germany’s leading critic at the time, Alfred Einstein, who immediately elevated the previously little-known Braunfels to the front rank of Germany’s opera composers:

“I believe that Germany’s opera stage has never been traversed by a more absolute artistic creation than this ‘lyrico-fantastical play after Aristophanes.’ It is one of the documents of the anti-naturalist movement in opera that has increasingly taken hold of composers over the last decade. Among the landmarks of this movement are the unreal stylistic balance of

Die Vögel, in short, was an unmitigated triumph. In Munich alone it received fifty performances, and it went on to conquer the leading operatic capitals of the German-speaking world: Berlin, Vienna, Stuttgart, Cologne, and many others. Together with Braunfels’s Te Deum, likewise premièred by Bruno Walter in Munich, it established its composer at the forefront of his generation. But with the sudden change of taste from post-romanticism to Neue Sachlichkeit in the mid-1920s, Braunfels found himself on the wrong side of an aesthetic divide, and his music gradually fell out of favor. If the Munich Opera could mount the work fifty times in the first two years of its existence, by 1927 Wilhelm Altmann, the operatic statistician of the leading musical journal Musik des Anbruch, could note only two performances in the whole of Germany (“most regrettably,” the ordinarily impassive Altmann remarked), and from 1928 there were no performances of it at all. With the ascent of Nazism in 1933 Braunfels’s music was banned wholesale, and after 1945 he again found himself on the wrong side of an aesthetic divide by refusing to espouse the new currents of the avant-garde.

The rediscovery of Die Vögel had to wait until 1971, almost two decadesafter the composer’s death, when a production of it took place in Karlsruhe. An unnecessarily modernist staging in Bremen followed in 1991, which did little justice to the rarified utopia that Braunfels tried to create out of Aristophanes’s broad-brushed satire. The work’s posthumous breakthrough finally came in 1996, when it was recorded by Lothar Zagrosek for Decca’s Entartete Musik series. Since then Die Vögel has been heard ever more frequently on the world’s stages: the Grand Théâtre in Geneva (2004, cond. Ulf Schirmer), the Teatro Lirico di Cagliari (2007, cond. Roberto Abbado), a concert performance at the Berlin Konzerthaus with video installations (2009, cond. Lothar Zagrosek), and most recently a well-received if somewhat garish production in Osnabrück (2014). The American première was given at the Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston, South Carolina, under Julius Rudel (2005), followed four years later by a staging at the Los Angeles Opera under James Conlon that has been released on DVD (2009). In short, one of the great achievements of German late-romanticism is again finding the audience that it held spellbound in the early 1920s, and that it so richly deserves today.

Cast of Characters

Goodhope, citizen of a big city – Tenor

Trustyfriend, citizen of a big city – High bass

Voice of Zeus – Baritone

Prometheus – Baritone

Hoopoe, once a human, now King of the Birds – Baritone

Nightingale – High soprano

Wren – Soprano

First Thrush – Low soprano

Second Thrush, Swallows I-III, Tits I-II – Six sopranos

Wrynecks I-IV – Four tenors

Peewits I-II – Two basses

Eagle – Bass

Raven – Bass

Flamingo – Tenor

Four Doves – Four contraltos

Three Cuckoos – Three basses

Chorus

Warblers and other birds, voices of the winds, voices of fragrance of flowers

Ballet scene

Male dove, female dove, other birds

Time and place

Both undefined.

Synopsis of the Plot

Prologue: Perched in a tree, the Nightingale welcomes the spectators. She sings of the joys and benefits of the birds’ life and pities humans for their restlessness and worries. In the end, however, she admits that even she yearns for something distant, unknown, and unattainable.

Act I, a rocky mountain landscape: Trustyfriend and Goodhope are seeking the realm of the birds in order to find a peaceful dwelling place. They are received by Hoopoe, the King of the Birds. Trustyfriend concocts the plan of building a city in the skies – Cloud Cuckoo Land – enabling the birds to secure their mastery of gods and men. The birds are summoned. At first they greet the men from the big city with animosity, but in the end they are excited by the plan and quickly set to work.

Act II, moonlit night in a mountain grove: In an extended lyrical dialogue with the Nightingale, Goodhope, a romantic and dreamy character in contrast to the man-of-action Trustyfried, is moved by a vision of the Infinite. The joyful excitement of the birds at the now finished city is crowned by a ballet scene with two doves, the first couple to move into Cloud Cuckoo Land. But the idyll is disturbed by the entrance of Prometheus, who warns them of Zeus’s wrath. Ignoring his warning, the birds proclaim war against the gods. It ends with the destruction of the city, forcing the birds to acknowledge the Zeus’s unassailable grandeur. Meanwhile the two men set out on their return journey. Trustyfriend, the more prosaic of the two, thinks of his warm stove, while Goodhope has been inwardly transformed by his romantic experience with the Nightingale.

Bradford Robinson, 2016

For performance material please contact Universal Edition, Wien.

Score Data

| Edition | Opera Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Opera |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 468 |