Pagan Symphony

Bantock, Granville

59,00 €

Preface

Granville Bantock

(b. London, 7th August 1868 – d. London, 11th October 1946)

Pagan Symphony

Preface

Granville Bantock should be known as one of Britain’s most important composers of the first third of the 20th century, even though he is virtually unknown nowadays and hasn’t been acknowledged with a complete monograph in the 70 years since his death. Bantock mainly composed vocal and choral music. Particularly noteworthy are his oratorios (amongst others Omar Khayyám, 1906, The Song of Songs, 1922 and Christus, 1901) as well as his unaccompanied choral symphonies Atlanta in Calydon (1911) and The Vanity of Vanities (1913), which are some of the first more complex counterpoint choral pieces in over 200 years in Great Britain.Bantock began his studies at the London Trinity College of Music under the guidance of Gordon Saunders. His later teachers at the Royal Academy of Music were Henry Lazarus, Reginald Steggall, Frederick Corder and Alexander Campbell Mackenzie. He was a lecturer at both conservatoires early on. In 1893 he became the leading editor of the Quarterly Musical Review. From 1897 to 1901 he was the musical director of the Tower in New Brighton and later accepted the call to be head of the School of Music of the Birmingham Midland institute (now Birmingham Conservatoire) and became Elgar’s successor as professor of music at Birmingham University in 1908 (he was knighted in 1930).

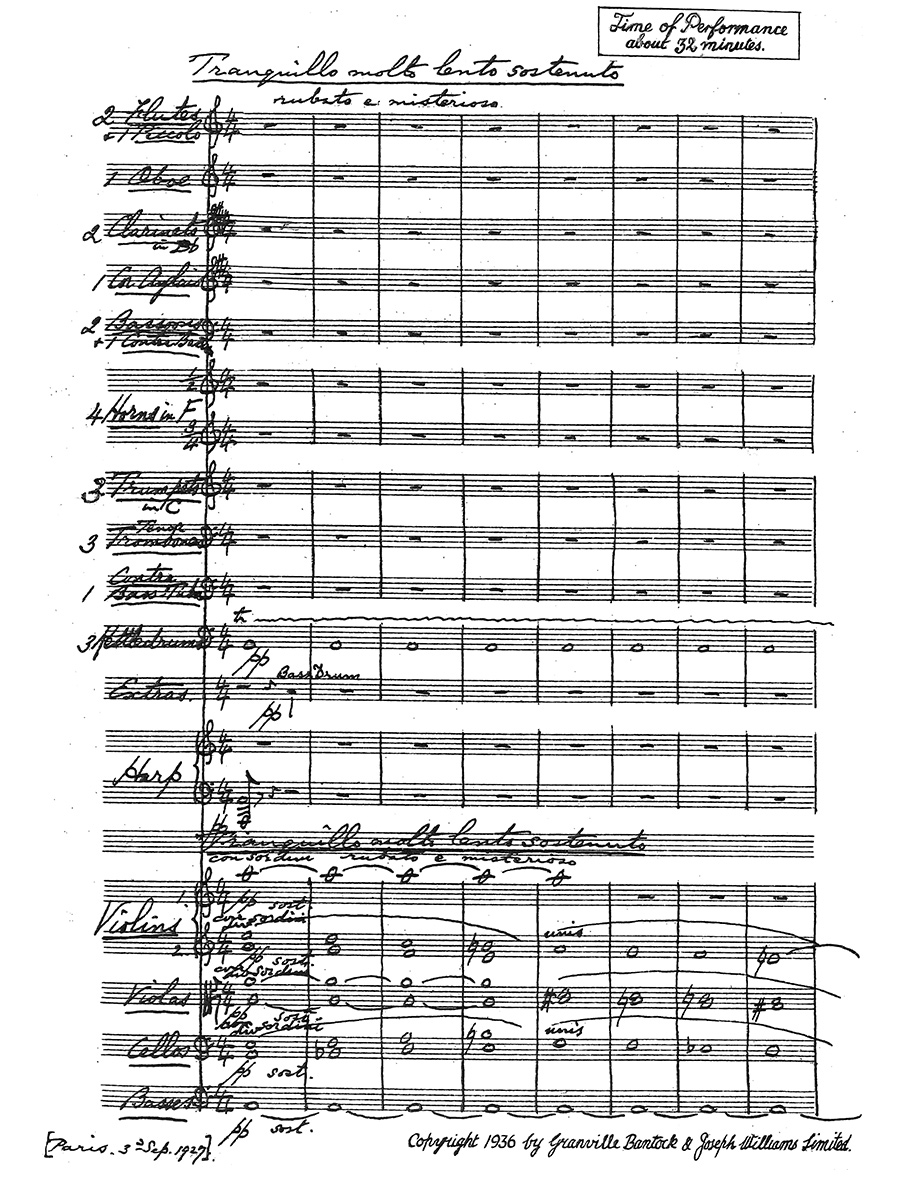

As a student of Frederick Corder at the London Royal Academy of Music, Wagner and more so Liszt were of great influence on Bantock which can particularly be seen in his tone poems (The Witch of Atlas, 1902, Fifine at The Fair, 1901), and in his programmatic symphonies. Especially these were largely popular amongst the British musical landscape at the beginning of the century. As for several other composers the first world war meant a break in popularity for Bantock. Retrospectively Bantock’s style has frequently been described as eclectic, though many of his works display a sort of creativity which may not be attributed to harmony but much more to the formal structure and the instrumentation which gained sustainable meaning but is hardly recognized thus far. Apart from these exceptional talents Herbert Antcliffe points to Bantock’s importance as a patron of his colleagues and thus says that the title of an »English Liszt« is very fitting. Bantock was said to be a good conductor and constantly supported the works of other artists (among them were Boughton, V. Williams, Harty and Bax). Furthermore he was a close and trusted friend to Havergal Brian, Josef Holbrook and others; Clarence Raybould, Julius Harrison, Claude Powell, Cecil Gray and Christopher Edmunds were among his students.The Pagan Symphony (1923-28) was partially developed from the unfinished second part of the choral ballet with vocal soli The Great God Pan: Festival of Pan. The ballet’s first part (whose eerie quality reminds Norman Demuth of Strauss) was published under the title Pan in Arcady in 1915 and premiered in Glasgow on 9th December 1919.

With Pagan Symphony, which Bantock dedicated to his son Raymond, he picks up the themes of mythical ancient Greece; the composer especially loved the time of the ancient world and the Orient – besides the aforementioned works Bantock’s Symphonic poem The Witch of Atlas 1902), the orchestral songs Sappho (1905), the overture Oedipus Coloneus (1911), the symphony The Cyprian Goddess (1938-39) and the Overture to a Greek Comedy (1944) are worth noting.

The Pagan combines the multi-movemental form of the traditional symphony within its own single-movemental form as did the Hebridean Symphony before it – though authors are still not quite sure when which movement begins and ends and how many movements actually exist. To the author of these lines it appears likely that the Pagan consists of four movements with a slow movement and a Scherzo (as identified in the score). The quasi first movement (with a slow introduction, exposition (from [3]), development (from [11] 2) and recapitulation (2 [21])) is mainly characterised by one theme and a further motif. The theme is processed and a certain reminiscence of Ravel (before [6]), Dukas, Strauss (4 [18]) and Saint-Saëns ([16]) is evident. Modal harmonies and the use of the quart interval point to contemporary composer colleagues (Nielsen) and particularly this special combination of traditional harmony with quartal and modal harmony make for Bantocks innovative potential.

The slow movement (from 4 [23]) starts with a violin solo but besides that the main theme and the motif from the first movement are often reused. The second half of the movement (from 2 [35]) is a fuge. Two metres lead over to the Scherzo (‘Dance of Satyrs’) (from [39]) which proves to be a further fuge. With its grotesque instrumentation it comes close to Janáček and Shostakovich’s opera Nos (1927-28). The ‘battle-scene’, as Havergal Brian calls it, is a percussion section followed by fanfares. The second Scherzo (another dance section) and the finale are so intricately intertwined that the second Scherzo (from [50]), which introduces a new theme, is the finale’s exposition. During the recapitulation ([77] 3) the theme reappears in its exact original form, whereas in the development section ([60]), which contains a passage »‘Poikilothron athanat Aphrodita’ (‘Immortal Aphrodite on your elaborate throne’)« (the title is borrowed from a poem by Sapphos), it is processed according to all the rules. In the recapitulation, which strongly reminds one of Strauss, Korngold, Elgar and others, and which Bantock calls »Finale«, numerous previously introduced themes and motifs reappear and are quasi summarised and revisited.

The Symphony bears the Latin motto »Et ego in Arcadia vixi« – apart from that Bantock doesn’t provide any clarification. A reference in a programme note which was presumably written by Bantock himself or at least approved by him, refers to Horaz’ Oden and especially the beginning of the XIX. Ode: „Bacchum in remotis carmina rupibus vidi docentum ‑ credite posteri – Nymphasque discentes et aures, capripedum Satyrorum acutas.“ (Bacchus I have seen on far‑off rocks ‑ if postenty will believe me ‑ teaching his songs divine to the listening Nymphs and to the goat‑footed Satyrs with their pointed ears.)

The music may be described as a vision of the past, when the Greek god Dionysus (Bacchus) was worshipped as the bestower of happiness and plenty, the lover of truth and beauty, the victor over the powers of evil. (Immortal Aphrodite of the broidered throne appears for a brief moment as the goddess of Love, to remind the world of her supreme power and glorious beauty.)“

The Symphony premiered on the 8th March 1936 and was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Adrian Boult; the score was published concurrently.

Translation: Jennifer Pace

Reprint of a copy from the collection Jürgen Schaarwächter, Cologne.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 284 |