Concerto for Flute and Orchestra

Reicha, Josef

14,00 €

Preface

Josef Reicha – Concerto for Flute and Orchestra

(b. Chuděnice, nr Klatovy, 12 Feb 1752–d. Bonn, 5 March 1795)

Preface

Josef Reicha is best known as the uncle of the Bohemian composer Antonin Reicha (1770–1836), though he was also a notable musician, composer, and conductor. Raised in the Bohemian market town of Chuděnice, he was first educated in music in the same way as other Bohemian children of the time, through his local school. In 1761 he moved to Prague, the center of music in Bohemia during the 1700s, to become a choirboy. It was there that he began to also study the cello and shortly after, began working as principal cellist in the court orchestra of Prince Kraft Ernst von Oettingen-Wallerstein.

In 1778, Reicha embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe with the Prince and visited many of the cosmopolitan centers of Europe. Records do not indicate when Reicha began composing his Concerto for Flute and Orchestra or when it was first premiered, though we know it was completed, as were his other works, at Wallerstein. The manuscript cover indicates its composition in September 1781. Reicha was likely inspired by what he heard and saw during his tour, based on the prevalence of galant musical characteristics throughout the concerto including a simple, song-like, and clear melody, short and periodic phrases, a reduced harmonic vocabulary that emphasizes the tonic and dominant, and a clear distinction between the soloist and accompaniment. The Concerto for Flute and Orchestra is written in three movements for two oboes, two horns (not specified if brass or basset), a flute soloist, violin I, violin II, viola I, viola II, and cellos and basses. Because the wind parts often double the string parts and do not, throughout most of the piece, present a significant performance challenge, the concerto may have been composed for the prince and his friends to play at home. Another plausible alternative is that Josef wrote the work for his adopted son, Antonin, to play when he became a court musician. We know that Antonin became a professional flutist in the Bonn court orchestra, which Josef directed.

Reicha’s concerto employs a unique spin on the traditional expectations of form in the eighteenth-century classical concerto to capture the audience’s attention. In addition, because of the contemporary convention by which flutists could also play the oboe, the concerto represents a dual function piece that works equally well for solo flute or oboe. It is not difficult to rehearse nor complex to perform, but has a beautiful solo part that makes it suitable for a wide range of performance venues from schools to professional concert halls.

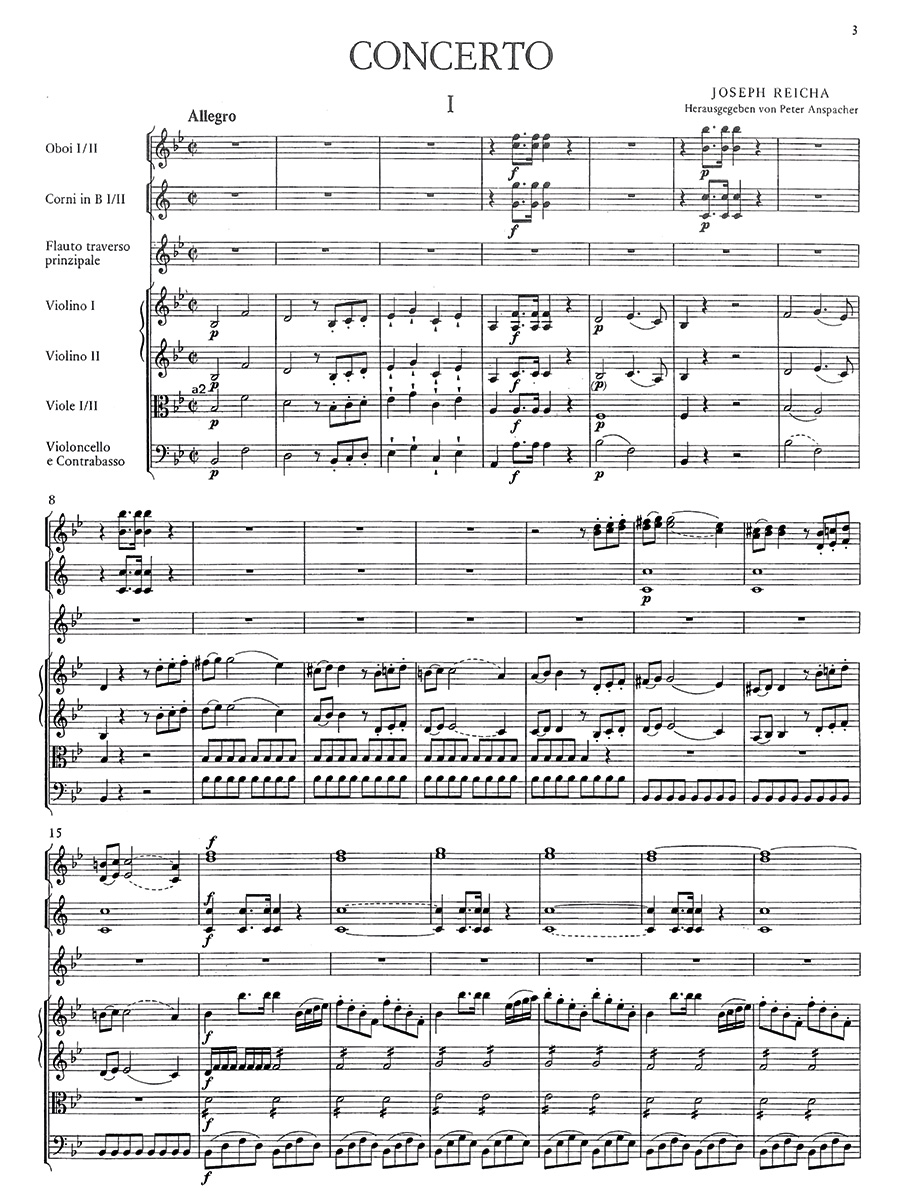

The first movement, an Allegro in B-flat major in sonata-allegro form, features clear thematic development. The tutti orchestra opens the work with an exposition of the theme before the solo flute enters at measure 62 to create a shortened double exposition. The movement follows sonata form expectations although Reicha does not compose a complete recapitulation. Although the melodic, harmonic, and accompaniment material from measure 25 returns in measure 149, the opening material from measures one through four does not return until measure 173. Because the recapitulation does not require the harmonic modulation expected in the exposition, the flute theme in the recapitulation remains free to highlight the virtuosity of the performer through complex rhythmic and technical passages of duple subdivisions juxtaposed against triple subdivisions. The second movement is an Adagio in rounded binary form, without repeats, in which the opening theme returns at the end of the movement. Reicha completes the concerto with a rondo form Allegro in B-flat major. The theme begins with the solo flute followed by an orchestral tutti, which typically opens such a movement. Reicha again plays with eighteenth-century formal expectations. The next sixteen measures are all dedicated to the soloist and an elaborate cadential figure modulates to the dominant key. Each subsequent period or double period is either a brief episode that explores melodic units of the rondo theme or another repetition of that theme.

The beauty of Reicha’s Concerto for Flute and Orchestra comes from both the design of the work and the artistry of the solo performer. Currently the only commercially available recording is a performance by Jan Adamus (oboe) and the Paradubice Chamber Orchestra produced by the Panton label in the Czech Republic. The court library of the Thurn and Taxis princes in Regensburg holds the manuscript parts from which this score is derived. The work provides a unique performance opportunity for flutists, oboists, and orchestras of almost any level. Students and amateur performers could enjoy performing this approachable classical-era concerto while professional orchestras could focus on foregrounding the melodies making its simple elegance come alive. The solo part does not pose any significant or unexpected technical challenges to either a flutist or oboist, and it explores a limited range of the flute, thus offering an opportunity for younger technically inclined students and enthusiast performers. The concerto provides an approachable glimpse into the eighteenth-century galant musical language.

Vanessa Davis, 2016

For performance material please contact Amadeus Verlag, Winterthur. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Solo Instrument(e) & Orchester |

| Format | 210 x 297 mm |

| Druck | Reprint |

| Seiten | 28 |