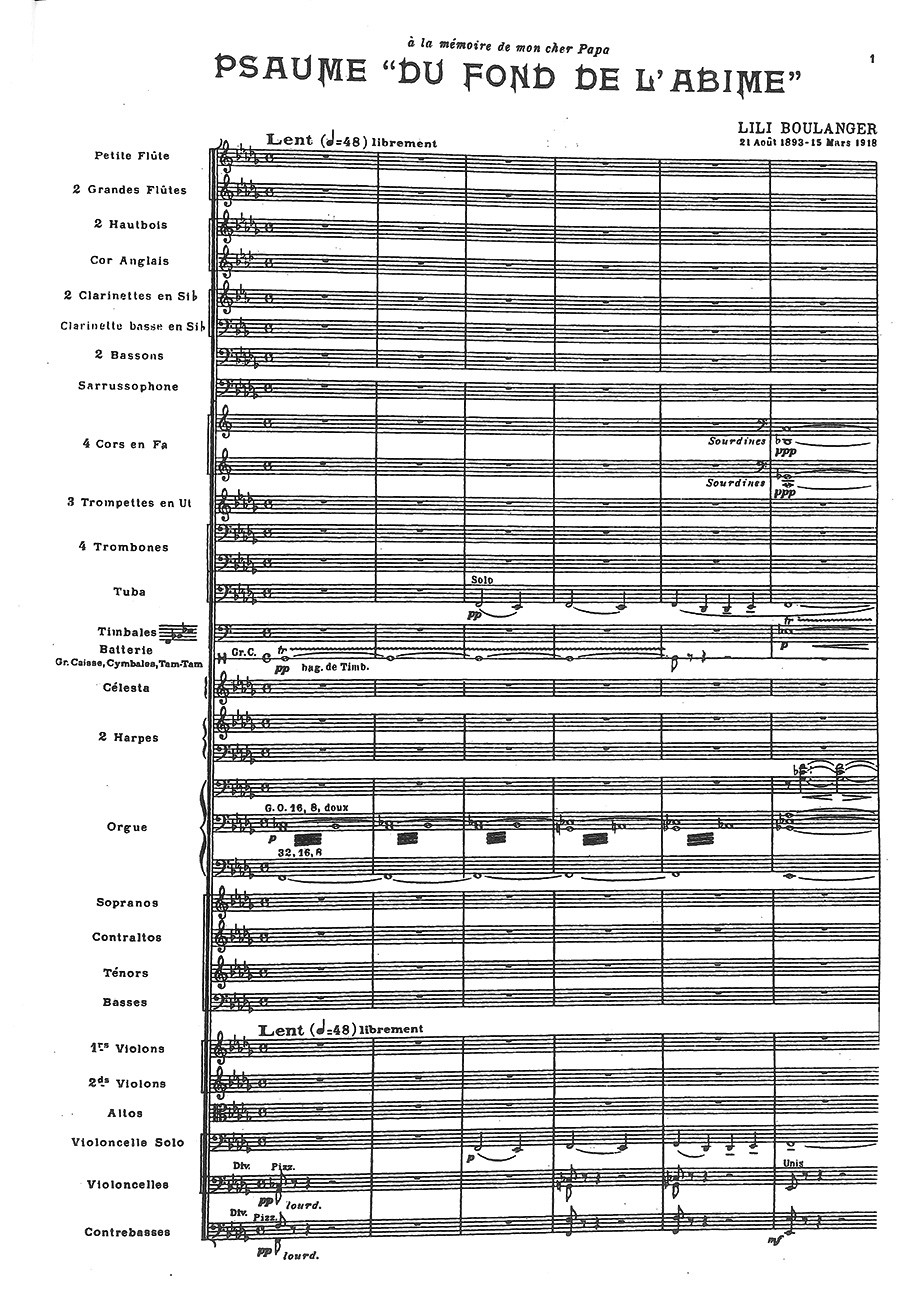

“Du fond de l’abîme”. Psalm 130 for voice & orchestra

Boulanger, Lili

27,00 €

Boulanger, Lili

“Du fond de l’abîme”. Psalm 130 for voice & orchestra

(geb. Paris, 21. August 1893 — gest. Mézy-par-Meulan, 15. März 1918)

“Du fond de l’abîme” Psalm 130

Lili Boulanger wurde von ihrer älteren Schwester Nadia als »erste Komponistin überhaupt« betrachtet. In der Tat änderte sie ungeachtet ihres allzu kurzen, von Krankheit und Leid geprägten Lebens das Ansehen der Frau in der Welt der Musik. Sie wurde schon in früher Jugend als musikalisch vielversprechend erkannt, als sie, am Klavier begleitet von Gabriel Fauré, einige Lieder sang, und so erhielt sie eine gründliche musikalische Ausbildung. Sie begleitete bald Nadia zu ihren Stunden am Pariser Conservatoire und erhielt später selbst Kompositionsunterricht bei Paul Vidal. Ihre stets fragile physische Natur

Ihre tief empfundene Musik fungiert anscheinend als einzige Äußerung persönlicher Reflexion und emo-tionaler Ergüsse einer begabten Musikerin, die gefangen war in einem Körper, von dem sie klar erkannt hatte, daß er nicht lange überleben würde. Eine gequälte Erkenntnis ihrer Situation hat einige Forscher dazu verleitet, ihr Werk als autobiographisch zu interpretieren (darunter Rosenstiel, 1978). Ich dagegen betrachte ihre schönen und hoch emotionalen Psalm-Vertonungen als musikalisch kühn, eine individuelle Behandlung der Dissonanz neben einem besonderen Gespür für das Orchestertimbre enthüllend, das strenge Farben betont. Auch hört man darin deutlich eine Vorliebe für das Blech, Schlagzeug und Mittelstimmen. Da diese Werke in der Umgebung der Ereignisse des ersten Weltkriegs entstanden, mag es nicht überraschen, wenn ich aus ihnen eine Bitte an die gesamte Menschheit heraushöre, ihre Mitmenschlichkeit zu erkennen. Auch Annegret Fauser war der Ansicht, Lili Boulanger habe hier drei »Gebete für den Frieden« geschaffen (Fauser, 2007). Eine so deutliche musikalische Äußerung war ihrerzeit bedeutend, und sie ist es noch heute. Und als hingebungsvolle Katholikin, die ihre Psalmen gut kannte, wählte sie ausgerechnet die Psalmen 24, 129 und 130 – dies ist bedeutungsvoll..

“Du fond de l’abîme”

Psalm 130

Die Komposition dieser epischen Psalm-Vertonung begann 1914, während des ersten Aufenthaltes von Lili Boulanger in der Villa Medici zu Rom. Durch den Kriegsausbruch und ihre sich verschlechternde Gesundheit zog sich die Fertigstellung lang hinaus. Es scheint, als ob sie bei ihrem zweiten Rom-Aufenthalt wieder an die Arbeit an dem Werk zurückkehrte, doch die Instrumentierung wurde erst im Herbst 1917 im Haus ihrer Familie in Gargenville fertiggestellt, also nach Beendigung ihres zweiten Rom-Aufenthaltes.

Lili Boulanger

(b. Paris, 21 August 1893 — d. Mézy-par-Meulan, 15 March 1918)

“Du fond de l’abîme” Psalm 130

Seen as “the first woman composer” by her sister Nadia Boulanger, in her extremely short life which was plagued by illness, Lili Boulanger changed the face of women in music. Identified as a promising musician at a very early age, singing songs with Fauré’s accompaniment at the piano, Lili received a thorough musical education. She had accompanied her sister, Nadia, to classes at the Paris Conservatoire and later received composition lessons from Paul Vidal. Her frail physical state however hampered her development and career prospects. Despite a serious intestinal condition she dedicated herself to composition as though it were a right of passage. Following her father Ernest (Grand Prix de Rome 1835) and sister Nadia (Second Prix 1908), she submitted herself for entry to the Prix de Rome in 1912, which she later withdrew from due to her health. But at the age of 19, in 1913 she made a second attempt, this time succeeding as the first woman to win the prestigious Prix de Rome in Paris which awarded time in Rome at the Villa de Medici. The result was striking not only due to her gender, but also due to the overwhelming majority vote she received from the jury: thirty-one votes to five (Schwartz 1997). Misogynistic remarks littered the press following the announcement of her win. A review in Le ménestrel (12 July 1913 [p. 227]) noted that her “first name seems to displease the purists: though she is the winner of the Prix de Rome, she is no less of a woman.” This prize brought with it a requirement to compose songs with orchestral accompaniment and piano reduction, with an emphasis on producing some large scale works and sacred music. (Details of the requirements of and events within the Prix de Rome can be found in minutes of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Procès verbaux, housed in the Archives of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in the Institute de France, Paris.)

Her heartfelt music seems to act as her only means of personal reflection and emotional outpouring of a trapped talented musician in a body which she clearly recognised would not survive for long. A tortured recognition of her situation has led scholars to read her work as autobiographical (among them, Rosenstiel, 1978). I see her beautiful and highly emotional psalm settings as musically daring, revealing an individual use of dissonance, along with an attention to orchestral timbre which emphasises strong colours. A penchant for brass, percussion and mid-range voices is clearly heard in her Psalms. Written surrounded by the effects of the First World War, there is perhaps no surprise that I hear a plea to all mankind to recognise their shared humanity. As Fauser has identified, Lili creates three “prayers for peace” (2007). Such a clear musical utterance is highly relevant both then and now. As a devoted catholic Lili would have known her psalms well, making her choice of three – Psalms 24, 129 and 130 – significant.

“Du fond de l’abîme”

Psalm 130

Composition of this epic Psalm setting began during her first stay at the Villa Medici in Rome, in 1914. With the outbreak of war and her deteriorating health it had a long gestation. On her second visit to Rome it seems she returned to the work, though she completed the orchestration of it at her family home in Gargenville, following her second departure from Rome, in 1917.

This work is immediately personal and one is well justified in interpreting this work alongside Lili’s biography as it is dedicated to her father who died when Lili was only 6 years old. Caroline Potter’s monograph (2006) outlines the content of Lili’s sketch books during this period, noting that Lili had many titles for this work, including “Song of personal feeling” (p. 97). The final title is the same as the first vocal entry, and although this seems less personal, it is more appropriate for a large scale work of this nature, which is for performance in the concert hall. With the success of the Prix de Rome behind her, this work marks her first significant departure as a mature composer, in which she forges her style and develops a symphonically cohesive choral setting of this psalm. It is often referred to as one of her masterpieces, along side her winning Cantata, Faust et Hélène (1913). Du fond de l’abîme (De Profundis) is also a large scale work which demonstrates her compositional and “spiritual maturity” (Palmer 1993). By this stage in her life, she would have been aware that her health was not going to improve (she had surgery during the composition of this work which proved to be unsuccessful). Despite this, she placed much energy and dedication to these psalm settings, which seemed to push her to the heights of her creative ability. For one so young Psalm 130 strikes the listener as a well matured, heartfelt work supported by a life-long of emotional experience: it is hard to imagine any listener not being left with a lump in their throat or a tear in their eye…

[fusion_highlight color=”#a80b17″ rounded=”no” class=”” id=””]>>> [/fusion_highlight] Read complete preface / Komplettes Vorwort lesen> HERE| Score No. | 1001 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Choir/Voice & Orchestra |

| Pages | 100 |

| Size | |

| Printing | Reprint |