Mignon Overture

Thomas, Ambroise

16,00 €

Preface

Ambroise Thomas

Ouvertüre zu Mignon (1866)

Kennst Du das Land, wo die Citronen blühn,

Im dunkeln Laub die Gold=Orangen glühn,

Ein sanfter Wind vom blauen Himmel weht,

Die Myrte still und hoch der Lorbeer steht.

Kennst du es wohl?

Dahin! Dahin!

Mögt’ ich mit dir, o mein Geliebter, ziehn.

So fängt es an, Mignons Lied in Johann Wolfgang von Goethes Roman Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre von 1795/96. Die etwa 12jährige Mignon singt es für Wilhelm Meister, der Schauspieler werden will, sein Elternhaus verlassen hat und sich auf Reisen befindet. Er hat dabei Philine, die mit einer Schauspielertruppe unterwegs ist, und in ihrer Gesellschaft auch Mignon kennengelernt. Wilhelm kauft letztgenannte dem brutalen Theateragenten ab und findet immer mehr Gefallen an ihr, was jedoch die Eifersucht Philines weckt. Mignon hat Angst, Wilhelm zu verlieren und singt dieses Lied, sich selbst auf einer Zither begleitend. »Sie fing jeden Vers feierlich und prächtig an, als ob sie auf etwas Sonderbares aufmerksam machen, als ob sie etwas Wichtiges vortragen wollte. Bei der dritten Zeile ward der Gesang dumpfer und düsterer; das ›Kennst du es wohl?‹ drückte sie geheimnisvoll und bedächtig aus; in dem ›Dahin! Dahin!‹ lag eine unwiderstehliche Sehnsucht, und ihr ›Laß uns ziehn!‹ [am Ende der dritten Strophe] wußte sie bei jeder Wiederholung derart zu modifizieren, daß es bald bittend und dringend, bald treibend und vielversprechend war.« So steht es bei Goethe, zu Beginn des dritten Buches. Wilhelm kennt das Land. Es ist Italien.

Mit Goethes Roman hat das Libretto, das Ambroise Thomas als Oper Mignon vertonte, nicht mehr viel gemeinsam. Die Librettisten bezogen sich hauptsächlich auf die Bücher zwei bis vier, machten statt Wilhelm Meister und der Darstellung seiner Lebenswege nun Mignon zur Hauptfigur und rückten ihren Konflikt mit Philine in den Vordergrund. Es entstand eine Dreiecksgeschichte, angesiedelt im romantischen Ambiente eines Wirtshauses im Schwarzwald, kontrastiert mit exotischem Kolorit: Mignon ist Teil einer umherreisenden Zigeunertruppe.

Die Romanze der Mignon (»Connais-tu le pays« / »Kennst Du das Land«), die sie im ersten Akt der Oper als ihre erste Arie singt (I/4), erscheint auch als erstes Thema der Ouvertüre nach der Einleitung (T. 27-52). Vom Horn expressiv gespielt, wird es, als Imitat einer Zither, zunächst nur auf der Zählzeit eins von der Harfe und den Streichern begleitet. Ab der Textzeile »C’est là! C’est là« / »Dahin! Dahin!« übernehmen Flöte und Violine die Melodie, die Begleitung der Streicher wird durch die Bläser unterstützt.

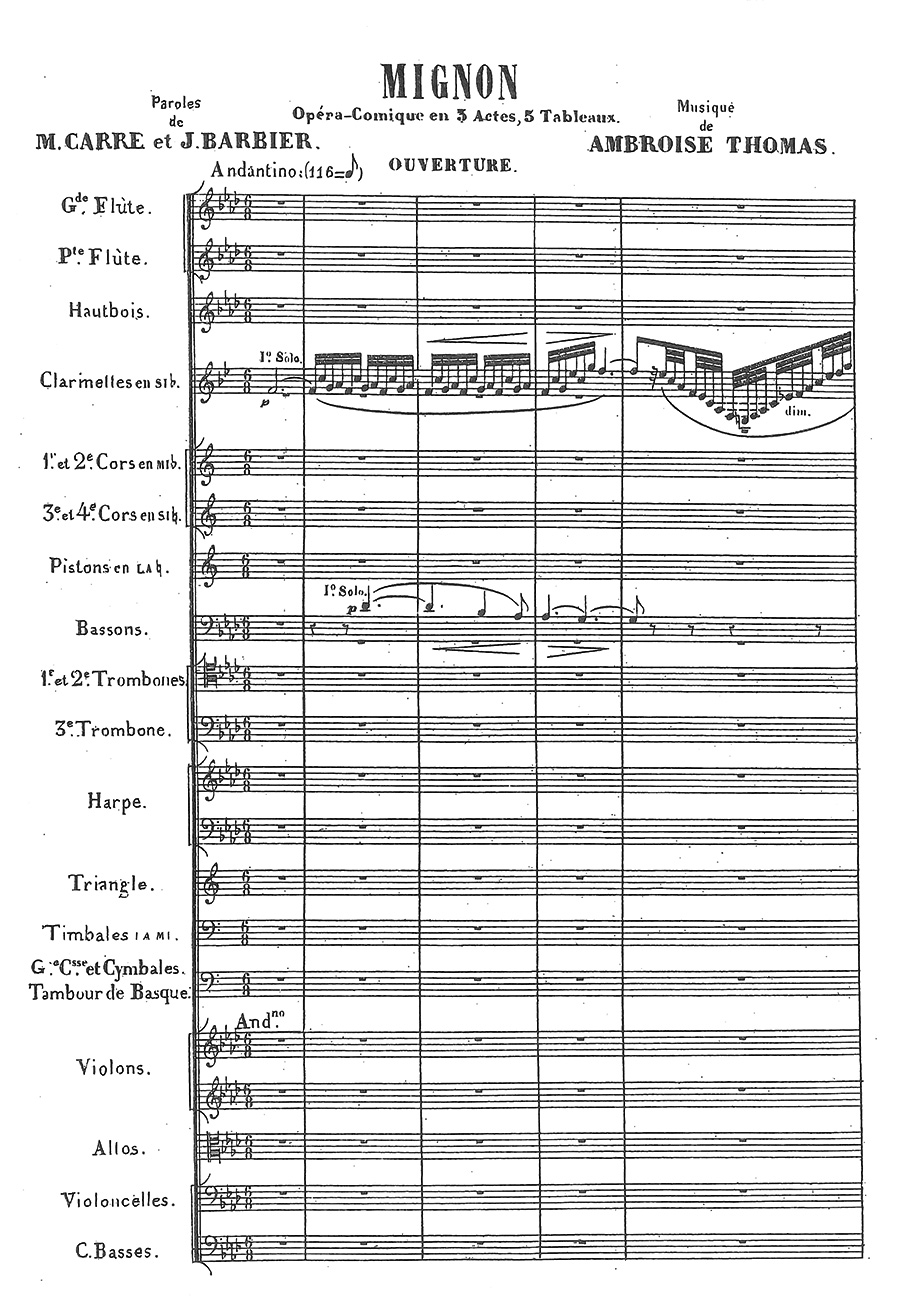

Vor Mignons Romanze im Andante besteht die Ouvertüre aus einem Andantino (T. 1-11) und einem Moderato sostenuto (T. 12-26). Das Andantino ist wiederum zweigeteilt: in den ersten sechs Takten spielt eine Soloklarinette zunächst mehrere wiederholte Dreiklangsbrechungen mit Wechselnoten im Ambitus einer Quinte, bis sich die Figur zur Oktave ausweitet, verharrt, und dann kaskadenartig erst tief nach unten und dann genauso hoch hinaus schnellt und den Ambitus auf fast drei Oktaven weitet. Aber das Tempo ist langsam, die Vortragsbezeichnung piano, so daß die Virtuosität recht verhalten daherkommt, vergleichbar den ebenfalls verhaltenen Koloraturen, die Mignon in ihrem Steyrischen Lied »Je connais un pauvre enfant« / »Kam ein armes Mädchen von fern« (II/10) singt. Unterlegt wird diese Dreiklangsfigur mit einer langsam abwärtssteigenden klagenden Linie des Fagotts. Alle anderen Instrumente schweigen. Diese ersten sechs Takte werden wiederholt, nun von Flöte und Oboe gespielt. So spiegelt dieses Andantino die stets lyrisch singende und leidende Mignon wider sowie gleichzeitig Thomas’ Sinn für neue Klangfarben.

Das Moderato sostenuto beginnt mit einem mehrfach wiederholten chromatischen Motiv – die düstere Atmosphäre bleibt erhalten. Die sich anschließenden, stets abwärts verlaufenden Harfenarpeggien (T. 15-24) symbolisieren Lothario, der sich am Ende der Oper als Mignons Vater herausstellt. Sein erster Auftritt (I/1), in dem er seine vor Jahren geraubte Tochter beklagt, wird mit Harfenarpeggien eingeleitet, die schon in der Ouvertüre zu hören sind. Im zweiten Akt, wenn sich Mignon umbringen will (II/12), da sie vermutet, Wilhelm an Philine verloren zu haben, verhindern Lotharios Arpeggien ihren Selbstmord. In der Ouvertüre scheint diese Stelle gemeint zu sein, denn die Arpeggien werden von einer zunächst langsam abwärtsschreitenden chromatischen Linie begleitet, die sich dann um sich selbst dreht, bis die Klarinette, die die Ouvertüre eröffnete, diesen Abschnitt beendet, um zu Mignons Romanze überzuleiten, die dann in T. 52 endet. 52 von insgesamt 195 Takten der Ouvertüre sind zwar etwa nur ein Viertel, aber da, nach einer kurzen Überleitung, ab T. 56 ein schnelles Moderato tempo di Polacca beginnt, werden die etwa acht Minuten, die die Ouvertüre dauert, ziemlich exakt in vier langsame und vier schnelle Minuten aufgeteilt mit dem Umschlagpunkt in T. 56.

Die erste Ouvertürenhälfte bezieht sich auf Mignon, die zweite auf Philine und ihre Bravourarie mit überschäumenden Koloraturen (»Je suis Titania« / »Titania ist herabgestiegen«, II/12), die sie fast direkt an Mignons soeben verhinderten Selbstmord singt. Philine hat in der Oper einen großen Auftritt als Titania in einer Aufführung von William Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum. Die bisherige kammermusikalische Besetzung der Ouvertüre, die in Mignons Romanze nicht über ein piano hinausgeht, weicht nun zunächst einem vollen Bläsersatz, der bei der Wiederholung des Themas ab T. 66 zu einem Orchestertutti ausgeweitet wird, zunächst noch im mezzoforte, sich dann über forte zum fortissimo steigert, und dieses bis auf kleine Ausnahmen. Erst bei dem im staccato gehaltenen zweiten Teil der Arie (T. 103) geht die Dynamik kurz auf piano zurück, um dann im langgezogenen Schlußteil (ab T. 145) wieder im fortissimo die Ouvertüre virtuos und wirkungsvoll zu beenden.

Während Philines Auftritt im Sommernachtstraum hat Lothario das Theater angezündet, da er Mignons Rachewunsch, das Theater möge in Schutt und Asche aufgehen, umsetzt. Mignon selbst kommt bei dem Brand fast um und wird im letzten Augenblick von Wilhelm gerettet, der nun erkennt, daß er sie liebt und nicht Philine. Gemeinsam mit Lothario bringt Wilhelm die Schwerkranke in eine Villa nach Italien, wo sich Vater und Tochter erst wiedererkennen. Es gibt vier verschiedene Fassungen der Oper mit ganz unterschiedlichen Schlüssen, mal tragisch, mal glücklich. In den tragischen Schlüssen stirbt Mignon, in den glücklichen werden sie und Wilhelm ein Paar:

1. Fassung französisch: UA 17. November 1866, Opéra-Comique, Paris

2. Fassung französisch: UA Ende November 1866, Opéra-Comique, Paris

3. Fassung deutsch: UA 4. September 1869, Theater der Stadt, Baden-Baden

4. Fassung italienisch: UA 5. Juli 1870, Drury Lane Theatre, London.

Als Thomas seine Oper schrieb, war er schon ein angesehener Komponist und seit 1856 Professor für Komposition am Pariser Conservatoire. Davor hatte er sich in den frühen 1830er Jahren mehrere Jahre in Rom aufgehalten, war durch Italien gereist und hatte Openraufführungen von Gioacchino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti und Vincenzo Bellini besucht. 1836 kehrte er für immer nach Paris zurück und konzentrierte sich auf die Komposition von insgesamt 20 Opern, die zwischen 1837 und 1882 uraufgeführt wurden. Daneben entstanden nur noch einige Lieder, Chorwerke und vereinzelt Instrumentalmusik. Thomas hatte in seinen Bühnenwerken bis 1850 hauptsächlich Opéras comiques geschrieben, Werke mit einer klaren Satzstruktur, kleiner besetzten Formen und ausgeprägter Melodik. Nach 1850 schloß er auch tragische Elemente, größere Szenen und eine differenziertere Instrumentation ein. Mit der Konzentration in Mignon und der Folgeoper Hamlet auf wenige Figuren und dem Hervortreten sentimentaler Züge entwickelten sich seine Opern in Richtung des Drame lyrique, wie es sich dann ausgeprägt bei Georges Bizet und Jules Massenet findet.

Erst mit Mignon gelang ihm der große internationale und auch langanhaltende Durchbruch, der zwei Jahre später mit der Uraufführung des Hamlet gefestigt wurde. Anlässlich der 1000. Aufführung seiner Mignon wurde Thomas 1894 mit dem Großkreuz der Legion d’honneur ausgezeichnet. Dabei war er zunächst gar nicht für Mignon vorgesehen gewesen. Erst nachdem Giacomo Meyerbeer, Charles Gounod (im Anschluß an den Erfolg seiner ebenfalls auf Goethe basierenden Oper Faust, 1859) und Ernest Reyer abgesagt hatten, wurde ihm der Stoff angeboten. Geschrieben hatten ihn Jules Barbier und Michel Carré, die bedeutendsten französischen Librettisten der 1850er und 1860er Jahre. Zu ihren Merkmalen gehört nicht die Originalität der Stoffwahl, sondern die Umwandlung von Meisterwerken großer Dichter. Insgesamt vier ihrer Libretti vertonte Thomas: Psyché (1857), Mignon (1866, nach Goethe), Hamlet (1868, nach Shakespheare) und Françoise de Rimini (1882, nach Dante).

Jörg Jewanski, 2012

Aufführungsmaterial ist von Bote und Bock, Berlin, zu beziehen. Nachdruck eines Exemplars der Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, München.

Ambroise Thomas

(b. Metz, 5 August 1811 – d. Paris, 12 February 1896)

Overture to

Mignon

(1866)

Know’st thou the land where lemon-trees do bloom,

And oranges like gold in leafy gloom;

A gentle wind from deep blue heaven blows,

The myrtle thick, and high the laurel grows?

Know’st thou it, then?

’Tis there! ’tis there,

O my belov’d one, I with thee would go!

Thus the opening stanza of Mignon’s song from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795-96). The roughly twelve-year-old girl sings it to Wilhelm Meister, who has left his parental home to become an actor and is now traveling. On his travels he meets Philine, a member of a wandering theatrical troupe, and in her company he also meets Mignon. Wilhelm buys her freedom from an abusive impresario and grows to like her more and more, kindling Philine’s jealousy. Mignon, fearful of losing Wilhelm, sings this song while accompanying herself on a zither. “She began every verse in a stately and solemn manner, as if she wished to draw attention towards something wonderful, as if she had something weighty to communicate. In the third line, her tones became deeper and gloomier; the Know’st thou it, then? was uttered with a show of mystery and eager circumspectness; in the ’T is there! ’tis there! lay a boundless longing; and her I with thee would go! she modified at each repetition, so that now it appeared to entreat and implore, now to impel and persuade” (Goethe, Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, Book III, trans. Thomas Carlyle). Wilhelm knows the land. It is Italy.

The libretto that Ambroise Thomas set to music in his opera Mignon has little in common with Goethe’s novel. The librettists drew mainly on Books II to IV, making Mignon the main protagonist instead of Wilhelm Meister and the vagaries of his life, and focusing on her conflict with Philine. The result was a love-triangle set in the romantic milieu of a tavern in the Black Forest and contrasting with exotic local color: Mignon is part of an itinerant band of gypsies.

Mignon’s Romance, “Connais-tu le pays” (Act I, Scene 4), is her first aria in the opera. It also forms the first theme of the Overture (mm. 27-52), following the introduction. Played expressively by the horn, it is initially accompanied by harp and strings playing only on the downbeat in imitation of a zither. Beginning with the line “C’est là! C’est là!” the flute and violin take over the melody, and the string accompaniment is supported by the winds.

Preceding Mignon’s Romance (Andante) are an Andantino (mm. 1-11) and a Moderato sostenuto (mm. 12-26). The Andantino again falls into two sections. In the first six bars a solo clarinet plays several repeated broken triads with cambiatas spanning the interval of a 5th. The figure then expands to fill an octave, remains transfixed, plunges far downward and soars equally far upward to cover an ambitus of almost three octaves. But as the tempo is slow and the dynamics piano, the virtuosity sounds quite subdued, much like the equally subdued coloraturas that Mignon sings in her Styrian Song “Je connais un pauvre enfant” (Act II, Scene 10). Supporting this triadic figure is a slowly descending, dolorous line in the bassoon. All the other instruments remain silent. These first six bars are then repeated, now played by the flute and oboe. In this way the Andantino reflects the character of Mignon, always suffering, always singing, as well as Thomas’ penchant for fresh timbres.

The Moderato sostenuto opens with several repetitions of a chromatic motif, retaining the atmosphere of gloom. The constantly descending harp arpeggios that follow (mm. 15-24) symbolize Lothario, who proves at the end of the opera to be Mignon’s father. His first entrance (Act I, Scene 1), where he laments the abduction of his daughter years ago, is introduced by harp arpeggios already heard in the Overture. In Act II Mignon, thinking that she has lost Wilhelm to Philine, contemplates suicide (Scene 12), but is prevented from killing herself by Lothario’s arpeggios. It is this scene that the Overture apparently refers to, for the arpeggios are accompanied by a descending chromatic line, slow at first, then spiraling on its axis until the clarinet that opened the Overture brings this section to a close. It then leads into Mignon’s Romance, which comes to an end in m. 52. These fifty-two of a total of 195 bars make up only a quarter of the length of the Overture; but as the tempo changes to a fast Moderato tempo di Polacca at m. 56 (after a brief transition), the eight-minute Overture falls fairly exactly into four slow minutes and four fast minutes, with the pivot point occurring at m. 56.

If the first half of the Overture relates to Mignon, the second relates to Philine and her aria di bravura with its coruscating roulades, “Je suis Titania” (Act II, Scene 12), which she sings almost immediately after Mignon’s abortive suicide. In the opera, Philine has a grand entrance as Titania in a production of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. The scoring, previously limited to chamber-music proportions and never exceeding piano in Mignon’s theme, now gives way to a full contingent of winds, expanded to an orchestral tutti with the repetition of the theme in m. 66. At first the dynamic level is mezzoforte, but it then proceeds to escalate via forte to fortissimo, with few departures. Not until the second section of the aria, played staccato (m. 103), does the dynamic level return briefly to piano, only to end with a brilliant and effective fortissimo in the extended concluding section (mm. 145ff.).

During Philine’s appearance in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Lothario sets the theater on fire, thereby carrying out Mignon’s dream of enacting revenge by reducing the theater to ashes. Mignon herself nearly perishes in the flames, and is rescued at the last minute by Wilhelm, who now realizes that he loves her rather than Philine. Together with Lothario, he brings the mortally ill girl to a mansion in Italy, where father and daughter finally recognize each other. There are four versions of the opera, each with a different ending, now tragic, now happy. In the tragic endings, Mignon dies; in the happy endings, she and Wilhelm become lovers:

Version 1, French: premièred 17 November 1866, Opéra-Comique, Paris

Version 2, French: premièred late November 1866, Opéra-Comique, Paris

Version 3, German: premièred 4 September 1869, Municipal Theater, Baden-Baden

Version 4, Italian: premièred 5 July 1870, Drury Lane, London.

When Thomas wrote his opera he was already a celebrated composer and, since 1856, a professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire. Before then, in the early 1830s, he had spent several years in Rome, traveled through Italy, and attended performances of operas by Gioacchino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Vincenzo Bellini. In 1836 he returned permanently to Paris and concentrated on opera, writing a total of twenty that were premièred between 1837 and 1882. Besides these he only composed a few songs and choruses and a smattering of instrumental music. Until 1850 Thomas’ stage works were mainly operas comiques, works with clear formal designs, light orchestration, and an emphasis on melody. Thereafter he also included elements of tragedy, large-scale scenas, and more sophisticated instrumentation. By focusing on a small number of characters and emphasizing sentimentality in Mignon and its successor, Hamlet, he turned in the direction of drame lyrique, a genre later cultivated by Georges Bizet and Jules Massenet.

Mignon brought Thomas his great and long-lasting international breakthrough, solidified two years later with the première of Hamlet. At the one-thousandth performance of Mignon in 1894 he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor. Yet he had not even been the first choice to compose Mignon: it was only after Giacomo Meyerbeer, Charles Gounod (following his own Goethe opera, Faust, of 1859), and Ernest Reyer had turned down the project that the libretto was offered to Thomas. It was the work of Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, the leading French librettists of the 1850s and 1860s, who stood out less for the originality of their subjects than by way they adapted great literary masterpieces. Altogether Thomas set four of their librettos: Psyché (1857), Mignon (1866, after Goethe), Hamlet (1868, after Shakespeare), and Françoise de Rimini (1882, after Dante).

Translation: Bradford Robinson

For performance material please contact Bote und Bock, Berlin.

Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Overture |

| Pages | 40 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |