Divertissement pour grand orchestre Op. 42

Sokolow, Nikolai

35,00 €

Preface

Sokolow, Nikolai – Divertissement pour grand orchestre Op. 42

(b. St. Peterburg, 26 March 1859 – d. Petrograd 27 March 1922)

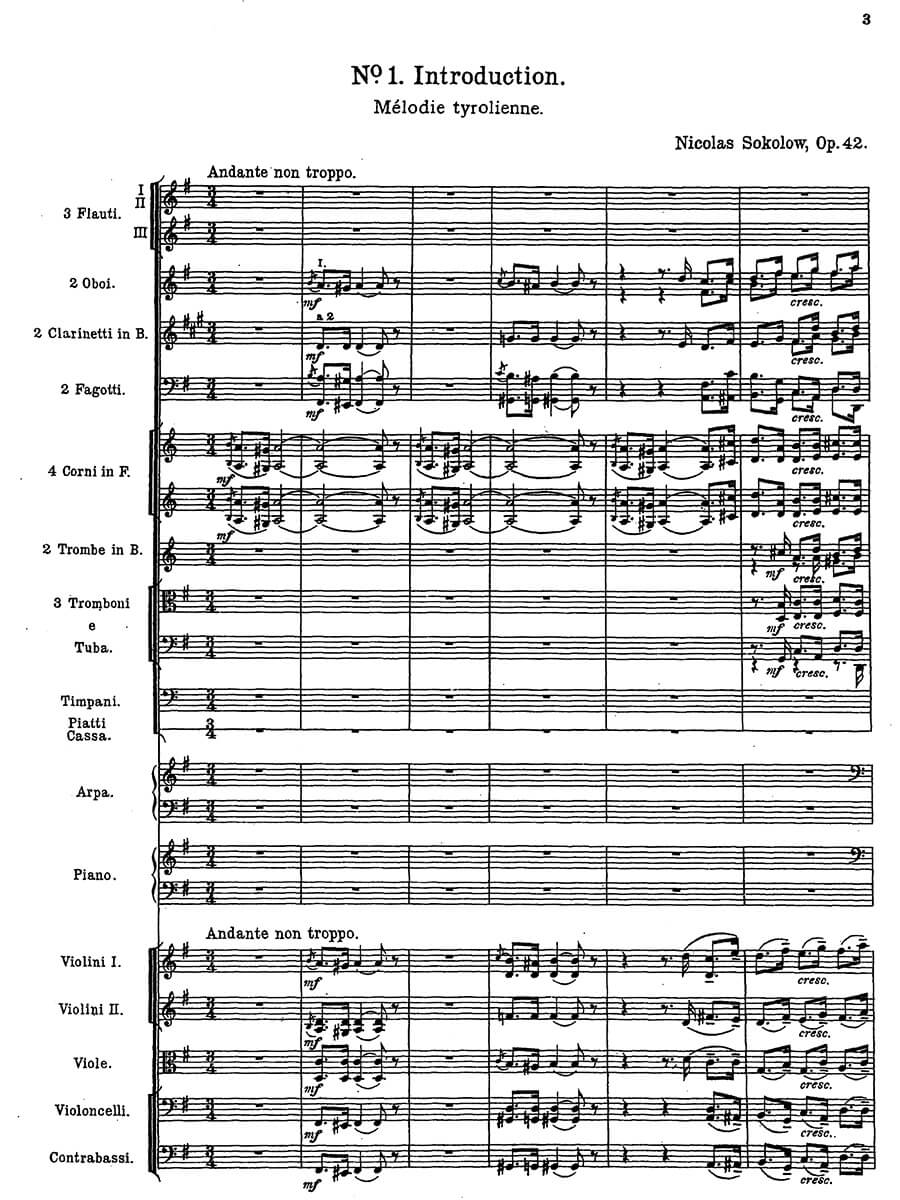

Introduction p.3

Mélodie Tyrolienne

À la czardas p.13

Elégie p.29

Solo de violon

Mélancolie p.37

Variation de ballet p.44

À l’espagnole en mineur p.48

En style héroique p.58

Complaintes p.67

Couplets

Grande valse de salon p.73

Final / Réminiscenses p.103

Preface

Composed during the last two decades of his life, Nikolai Sokolov’s Divertissement Op. 42 for symphonic orchestra represented the robust technicalism yet artful musicality produced from rigorous study within the conservatory-driven, Germano-centric aesthetic doctrines of the Russian late-19th to early 20th centuries. However, counterbalancing this was a pull towards the Exotic fragrance of national music from lands far away, the captivating allure of effortless and sumptuous evenings, melancholy and nostalgic evocations, and triumphant pronouncements of heroism. Throughout the work’s ten movements, allusions to many things, from Hungarian folk music and its nationalist joviality, to the chaste strains on Francophile medievalism and the dotted merriment of Western Austrian folk music, Sokolov creates a musical tapestry woven from many disparate trends across Romanticism, Impressionism, and early-Modernism. Demonstrating a unique synthesis of foreign and domestic compositional influences, a work of such caliber typifies the frustrated and, in many respects undesired, transition from 19th-century decadence and grandeur to 20th-century modernity. It is rather apparent that Sokolov’s place in (Russian) music history is as a footnote in the larger transitional space of the late-19th to pre-Revolution 20th century, his legacy almost exclusively governed by his relationship to music publishing mogul, impresario, and patron Mitronfan Belyayev. Musicologist Richard Taruskin called him “the Belyayevets composer.”1 In any case, Sokolov’s life, dominated by his theoretical and grosser pedagogical work at St. Petersburg Conservatory, generated a sizeable oeuvre, spanning across the gamut of categorical possibilities, from string quartets (Op. 7, 14, 20) and lieder, choruses, and romances, to chamber music (Op. 25, 45, 17) and larger orchestral works (Op. 44, 40, 18). One of the more popular works which is still known today in the repertoire is the collaborative work from within Belyayev’s creative circle, “Les Vendredis”.16 string quartets written by various members of the circle including better-known figures like Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov (Sokolov’s composition teacher), Liadov, and Borodin, among notable others. Within the Western purview, most, if not all, of Sokolov’s music remains unappreciated and unheard, some of the most exquisite examples found from his romances (Op. 10, 9, 41), of which little has been formally recorded. One of Sokolov’s important works, the “String Trio in D minor” (Op. 45), is a classical example of Russia’s late-19th century turn towards chamber music, a popular trend being the “trio élégique.”

Despite the historiographical deficiencies regarding Sokolov’s compositional achievements, when it comes to his pedagogical work, he descended from the Rimsky-Korsakovian lineage like many lauded and well-respected others (Stravinsky, Steinberg, Respighi, Prokofiev, Myaskovsky). This, despite the dismissive comments by Rimsky-Korsakov later about Sokolov against his “dry and lifeless” writing.2 Sokolov went on to be Dmitry Shostakovich’s first teacher in the art of counterpoint and fugue. So fondly did Shostakovich look back at his time with Sokolov that in 1922, the 26 year-old composer dedicated his Op. 3 (Theme and Variations in Bb major for orchestra) to him. In hindsight, it’s unsurprising that Sokolov fell between the cracks of classical music’s changing zeitgeist, as many other transitional figures like the neo-Scriabinist Nikolai Obukhov and the sons of J. S. Bach, namely C. P. E. Bach and J. S Bach. Further still is the dissonance of musical worldview expressed in composers like Camille Saint-Saens, Richard Strauss, Nikolai Medtner, and even Alexander Glazunov, the well-beloved Anton Arensky, and the stalwart technician Rimsky-Korsakov, and the rapidly changing world around them. Especially salient for Sokolov was the conditions of early-20th century Russia. Revolution was in the air, the failed 1905 revolution, while the aromas of Neo-Romanticism in the form of Mysticism, Impressionism, Neoclassicism, and early-Futurism swirled around a social memory rife with equal parts nostalgia and regret for the past, vengeance and retribution on the mind, and fear-motivated hope for a revolutionary future. Given that the “National School,” that is Slavophile composer Mily Balakirev’s attempt to create a self-sustaining autodidactic compositional movement independent from Western influence (the “Balakirev Circle”), and the larger project of musical nationalism had become outdated, it was de rigueur to abide by academic modalities. This is not to say everyone participated but it is to say the larger milieu was recovering from Slavophilism and quasi-Wagernism of the decade before by returning to formalities eschewed by realism on the one hand and birthing Modernism on the other. …

read more / weiterlesen … > HERE

Score Data

| Score Number | 4933 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 144 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |