Ascanio (in two volumes with French libretto)

Saint-Saëns, Camille

72,00 €

Preface

Camille Saint-Saëns

Ascanio

(1887-88)

(b. Paris, 9 October 1835 – d. Algiers, 16 December 1921)

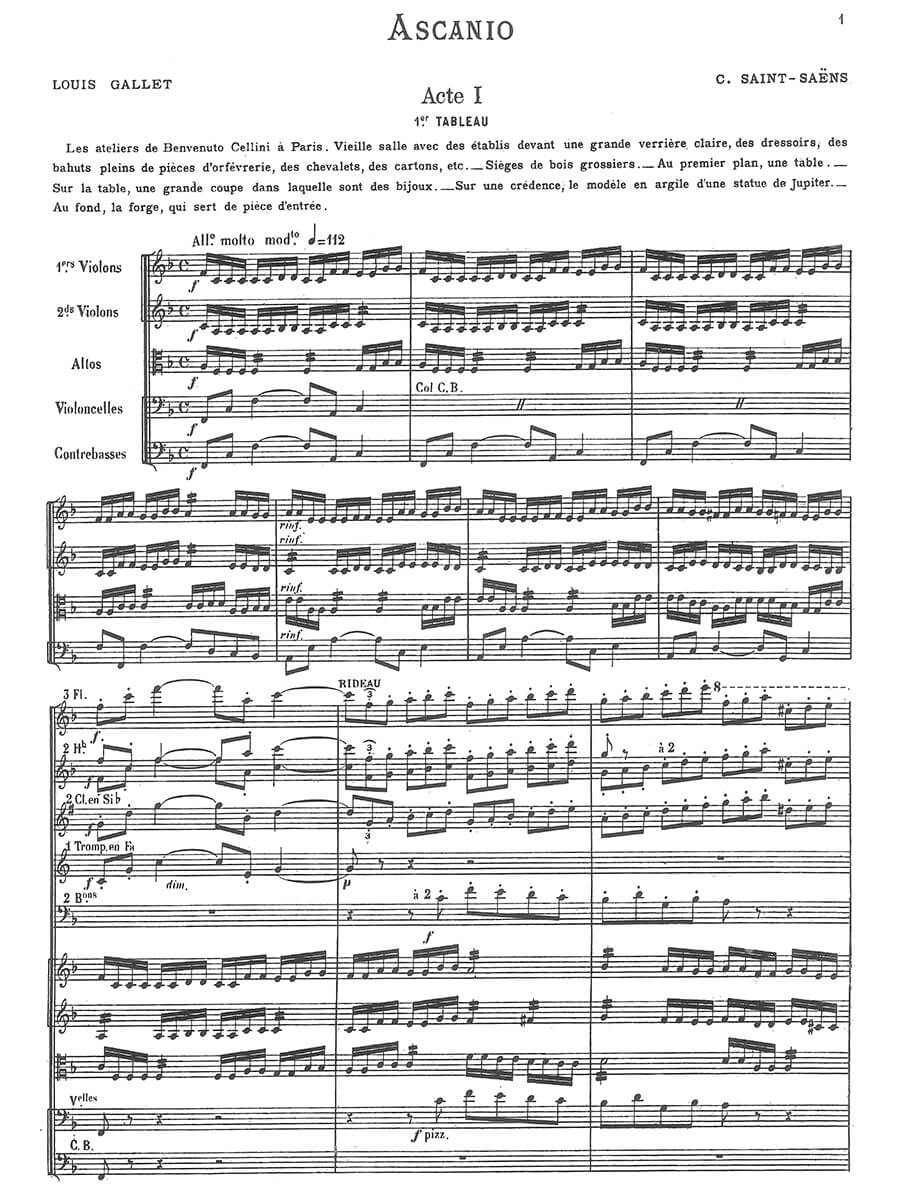

Opera in five acts and seven scenes

on a libretto by Louis Gallet

Preface

In 1886 the fifty-year-old Camille Saint-Saëns, having triumphed as a child prodigy, a virtuoso pianist, and, since the performance that year of his Third Symphony (the “Organ Symphony”), as a composer of instrumental music, jotted down a brief fictitious autobiography of a composer well into his fifties who was forced to watch mediocrities achieve glory on the operatic stage while he himself suffered neglect and ignominy. Nominally this composer was supposed to be Rameau, but in fact the piece was a thinly disguised account of his current predicament. His operatic masterpiece Samson et Dalila – begun in 1867, completed in 1873, and premièred to great effect by Liszt in Weimar in 1877 – had yet to be given a hearing anywhere in France; and there was a general feeling among the musical higher-ups that anyone of Saint-Saëns’ background was not to be trusted with the human voice, still less with a commission for the theater. Saint-Saëns promptly set about rectifying this situation by directing his ever-facile pen to the composition of opera, producing two scores within the space of as many years, and five more at regular intervals after that. The second piece in this late flowering of opera, and his seventh opera altogether, was Ascanio.

Ascanio had an auspicious beginning: it was solicited by the Paris Opéra with the intention of being premièred at the 1889 Paris Exhibition before the assembled leading lights of the international world of music. On 26 September 1887 the Opéra’s directors agreed to have Saint-Saëns write a new work on the subject of the Renaissance sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, drawing on a play of that same title by Paul Meurice (1818-1905) that had been successfully produced in Paris in 1852 and was in turn based on a novel, Ascanio, written jointly by Meurice and Alexandre Dumas père in 1843. The choice of subject was propitious: Saint-Saëns was personally acquainted with the playwright, and agreement was easily reached about the transformation of the play into an opera libretto. This task was handed to Louis Gallet (1835-1898), a prodigiously voluminous writer who had already turned out opera librettos for Bizet, Gounod, Massenet, and indeed Saint-Saëns himself (La princesse jaune, 1871; Étienne Marcel, 1878; Proserpine, 1886). Meurice put his seal of approval on Gallet’s text in November 1887, and Saint-Saëns immediately set sail for Algiers to compose the score in tranquility. After overcoming a momentary writer’s block, he found the composing “easy to do,” and the music flowed swiftly from his pen: the first two acts were drafted in February 1888, the third on the 18th of the following month, and by August the entire work was finished except for the ballet divertissement. This latter section, perhaps the most remarkable and certainly the most famous part of the opera, was soon completed in piano score after Saint-Saëns had returned to France. Here, drawing on episodes from mythology replete with naiads, dryads, and bacchantes, the composer created a charming faux-Renaissance pageant using themes and devices from earlier French opera, even to the point of quoting a melody from Thoinot Arbeau’s Orchésographie (1588). (Indeed, it has been suggested that the prospect of recreating the courtly atmosphere of early sixteenth-century Paris was Saint-Saëns’ principal motive for taking up the rather grisly and overly melodramatic subject-matter of Meurice’s play.) Renamed Ascanio to avoid comparison with Berlioz’s own Benvenuto Cellini (1838), the finished score was dispatched to the Opéra to enter production in time for the Paris World Exhibition.

Then disaster struck: Saint-Saëns’ mother died on 18 December 1888, and the composer was left completely devastated. Suffering from severe depression and insomnia, he went into hiding, traveling to Algiers under an assumed name in March 1889 and eventually winding up incognito in the Canary Islands, where he spent his time writing poetry and trying to take part in a local production of Rigoletto (being entirely unknown, he was dismissively turned down). The French press speculated about his fate and whereabouts: his death was publicly announced (producing claimants on his estate), and sightings were reported as far away as Java. The immediate result of his absence, however, was that he was unable to supervise the production of Ascanio, which was left in the hands of his librettist Gallet. Delays ensued: the sets were not ready in time; the role of Scozzone, originally intended for a contralto, was recast and had to be rewritten for soprano; and the Paris Exhibition came and went without a performance of the new opera. When, after several further delays, the première finally took place at the Paris Opéra on 21 March 1890, Saint-Saëns was still living under an assumed name in Las Palmas. Nor was he able to attend the triumphant first French performance of Samson et Dalila, given in Rouens two weeks earlier (before then it had been heard only in Germany, and always in German translation).

The première of Ascanio was a glittering affair with brilliant sets, equally brilliant singing (the role of Colombe was taken by the future star Emma Eames, then twenty-four years old), and a highly approving audience. Though critics were divided as to the work’s overall quality, Ascanio, its score tightened by the composer after the première, achieved a highly respectable run of thirty-three performances in 1890 and another three in 1891 before it was dropped from the Opéra’s repertoire. Then, on 6 January 1894, a fire in the Opéra’s warehouse destroyed the stage décor, rendering further performances impossible. By then Samson et Dalila had done the rounds of France’s provincial opera houses and had finally received a production at the Opéra in 1892, almost twenty years after its completion. The resounding success of Saint-Saëns’ earlier opera cast a shadow on Ascanio from which it has never emerged. A revival took place in Bordeaux in 1911, and in 1921 it was again heard at the Paris Opéra with the original sets carefully reconstructed. But this production, conducted by Reynaldo Hahn, vanished after six performances. It was the last to occur in Saint-Saëns’ lifetime. Since then, little has been heard of Ascanio. There is to date no complete commercial recording, though several excerpts exist on record: a live performance of Scozzone’s Fiorentinelle by Régine Crespin (1969), for example, and a curious historical recording of the same number by Meyrianne Héglon, with Saint-Saëns himself at the piano (1904). The mythological divertissement has, however, taken on a life of its own, with the Airs de ballet d’Ascanio for flute and orchestra (or piano) becoming a standard and welcome repertory item for ambitious flutists. This delightful divertissement, an early essay in musical historicism, was aptly summed up by the work’s great champion, Reynaldo Hahn as “a supreme triumph of taste and elegance – the entire Renaissance in a few pages.”

Cast of Characters

Benvenuto Cellini – Baritone

Ascanio – Tenor

François I – Baritone

A Beggar – Baritone

Charles V – Bass

Pagolo – Bass

d’Estourville – Tenor

d’Orbec – Tenor

Duchesse d’Etampes – Dramatic soprano

Scozzone – Contralto

Colombe d’Estourville – Soprano

An Ursuline Nun – Soprano

Dame Perine – Silent role

Chorus and supernumeraries

laborers, guild members, Benvenuto’s apprentices, ladies and gentlemen

at the court of François I, guards, populace

Ballet

dancing masters, nymphs, Venus, Juno, Pallas, Diane, Dryads, Naiads, Bacchus, Bacchantes,

Apollo, the Nine Muses, Cupid, Psyche, Erigone, Nicaea, a Page as Hesperian Dragon

Time and Place

Paris, 1539

Synopsis of the Plot

Act I, Scene 1, Cellini’s atelier: King François I has fetched the famous sculptor and goldsmith Cellini from Florence to Paris in order to surpass his rival Charles V as a patron of the arts. Cellini has brought along his lover Scozzone and his favorite pupil and adopted son Ascanio. Ascanio is in love with Colombe, the daughter of the Bailiff of Paris. Colombe has also secretly won the heart of Cellini, who recognizes in her his long-sought model for a statue of Hebe. Scozzone views her as a rival, but does not yet know her name. Ascanio has received an anonymous love letter, which was sent to him not by Colombe but by the King’s current mistress, the Duchesse d’Etampes, Scozzone’s foster-sister and confidante. Scozzone realizes that the young and naïve Ascanio is in danger of becoming the King’s rival. The King and his courtiers visit Cellini in his atelier, where work is underway on a reliquary for the Ursuline Nuns and on a golden statue of Jupiter, which the King wants to acquire as quickly as possible. To give Cellini the necessary working space, the King summarily places Estourville’s palace at the disposal of the artists. He also orders Estourville to prepare a banquet in honor of Charles, whose arrival is expected in Fontainebleau. Cellini has thus unintentionally drawn the enmity of the Parisian nobility. Scene 2, a square in front of the Augustinian Monastery and the Great and Little Nesle Palaces: For the first time Ascanio meets his secret love, Colombe. Her father, Estourville, initially resists the royal command to vacate his palace. The Duchesse, masked, approaches Ascanio. He recognizes her through her disguise and declares a “war without mercy” on her. A duel ensues, and only Colombe’s intercession prevents her father from falling victim to Cellini’s dagger. The goldsmiths move into their new atelier.

Act II, Scene 1, Cellini’s atelier in the Grand Nesle Palace: Ascanio recognizes the features of his beloved Colombe in the statue of Hebe, but keeps silent so as not to offend Cellini. In the meantime the Duchesse has arranged for Colombe’s engagement to Orbec. She has also concocted a letter informing Cellini that he has fallen out of favor with the King but is nevertheless obligated to deliver the statue of Jupiter. Cellini then turns to Charles, who is equally interested retaining his services. Scene 2, a room in the Louvre: This is the realm of the Duchesse. She plans to have Charles arrested during his visit, ensuring that François will reign over all of Europe. Knowing nothing of this, Ascanio hands her a diamond-encrusted lily which she has ordered. Encouraged by her friendliness, he confesses his love for Colombe. The Duchesse swears terrible vengeance.

Act III, boxwood garden at Fontainebleau: Cellini takes advantage of the presence of the rival rulers. He promises François that the statue will be delivered within three days if the King is able to fulfill his only wish: to prevent Colombe’s marriage to Orbec. But the Duchesse announces that Colombe’s wedding will take place the following day. The banquet is crowned by a magnificent ballet with scenes from mythology.

Act IV, same as I/1: Pagolo, a scheming guild member, has brought the Duchesse and Scozzone to the atelier, where the two women become witnesses to a plan to abduct Colombe in the finished reliquary for the Ursulines. The jealous Scozzone agrees with the scheme to have the shrine taken first to the Duchesse, where it will be opened only after three days, thereby cruelly ridding herself of her rival. Cellini, realizing that Colombe’s love belongs to Ascanio, declares her free to choose as she wishes. Scozzone desperately ponders how to ward off the approaching disaster. Two women, one in the reliquary, the other as escort, leave the atelier undisturbed by the courtiers, who are already alarmed at Colombe’s disappearance.

Act V, a place of prayer before a gigantic room in the Louvre: The Duchesse silently gloats in triumph as the reliquary is brought to her quarters. Cellini enters the palace in a festive procession with the completed statue of Jupiter. Neither the King nor the Duchesse is averse to his request to proceed with the union of Ascanio and Colombe. But they watch in horror as Colombe is led into the room by the Ursulines. The woman in the reliquary is Scozzone –dead! Cellini, frantic, recognizes the greatness of her love.

Bradford Robinson, 2014

Score Data

| Edition | Opera Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Opera |

| Pages | 452 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |