First Symphony in D-minor op.13

Rachmaninoff, Sergey

52,00 €

Preface

Rachmaninoff, Sergey – First Symphony in D-minor op.13

Preface

The premiere of Rakhmaninov’s first symphony is a notorious instance of a disastrous performance, reviewed by a malicious critic. This event is the more remarkable as the symphony’s first performance was eagerly awaited by his fellow musicians.

Much was expected from the talented young man. He was educated in Moscow by famous teachers like Anton Arensky and Sergey Taneyev. His graduation piece, the opera Aleko (MPH 2028), was a big success and earned him the Great Gold Medal in 1892.

In Petersburg Rakhmaninov was already known as an accomplished pianist. He had written and performed short pieces for his instrument, including the eventually world-famous C-sharp minor prelude, op.3 no.2. The success of his orchestral fantasy The Rock (MPH 1619), first performed in Moscow in 1894, had also not escaped the attention of music lovers in Petersburg.

The first performance of the symphony in that city on 15/28 March 1897 was a major event. Many of Petersburg’s top music people were present, like Rimsky-Korsakov, the critic Stasov, the critic and composer Cesar Cui and the Maecenas and publisher Mitrofan Belyayev.

Sergey Taneyev travelled from Moscow to attend the concert. Alexander Skryabin, who lived there too, wrote to Belyayev a few days before the premiere: “Please write me which impression Rakhmaninov’s symphony made”.

However, the performance was a failure. Various explanations have been offered. Although Alexander Glazunov had more than ten years experience as a conductor, his performance was sloppy. Glazunov had lacked sufficient rehearsal time for a concert program containing three premières. Several witnesses suggested that his addiction to alcohol was a major factor as well. The composer was not satisfied with the performance and would have rather conducted himself. Most of the people present at the rehearsal on the day before corroborated Rakhmaninov’s poor opinion of Glazunov’s conducting.

Rakhmaninov had added the epigraph “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord” (Romans, XII, verse 19) to the score (in the course of the symphony the Dies Irae is sometimes alluded to). The audience was astounded by the vehemence of the music.

The majority of critics responded unfavourably. Rakhmaninov was accused of decadency and extreme modernism. He was upbraided for merely striving after novel orchestral colours. Cui wrote a scathing review, in which he suggested the symphony illustrated the Plagues of Egypt, as depicted by a student of a conservatory in hell. A year before he had published a very critical review of The Rock (see above).

Anyway, the poor reception by public and critics was unexpected. His friends, especially those who had not been able to travel to Petersburg, were greatly disappointed. The disillusioned composer disappeared from Petersburg and fell into a period of deep depression, from which he only gradually recovered.

It is often said that Rakhmaninov did not resume composing music for three years because of this failure, but Savva Mamontov, the owner of the Moscow private opera, had engaged him to conduct more than a dozen operas in the next season. Initially, he simply was too busy to compose major works, while he embarked on a brilliant career as a conductor. He declined Mamontov’s offer to prolong his contract for the 1898-1899 season. The young musician made a concert tour abroad and reflected on his future. He finally got over his depression and concentrated on composition. In 1900 he surprised the world with his second piano concerto, still one of the most popular of its kind.

The original score of the symphony was lost, either torn up by its author or destroyed by a fire in Rakhmaninov’s house in 1917. After Rakhmaninov’s death in 1943, the musicologist Alexander Ossovsky (1871-1957), who remembered the history of the work, started a search for the orchestral parts. He managed to unearth enough material in the archives of the Petersburg conservatory and of the Belyayev Publishing House to enable the score being reconstructed. Eventually, B.G. Shal’man carried out that task successfully under the supervision of the well-known conductor Alexander Gauk.

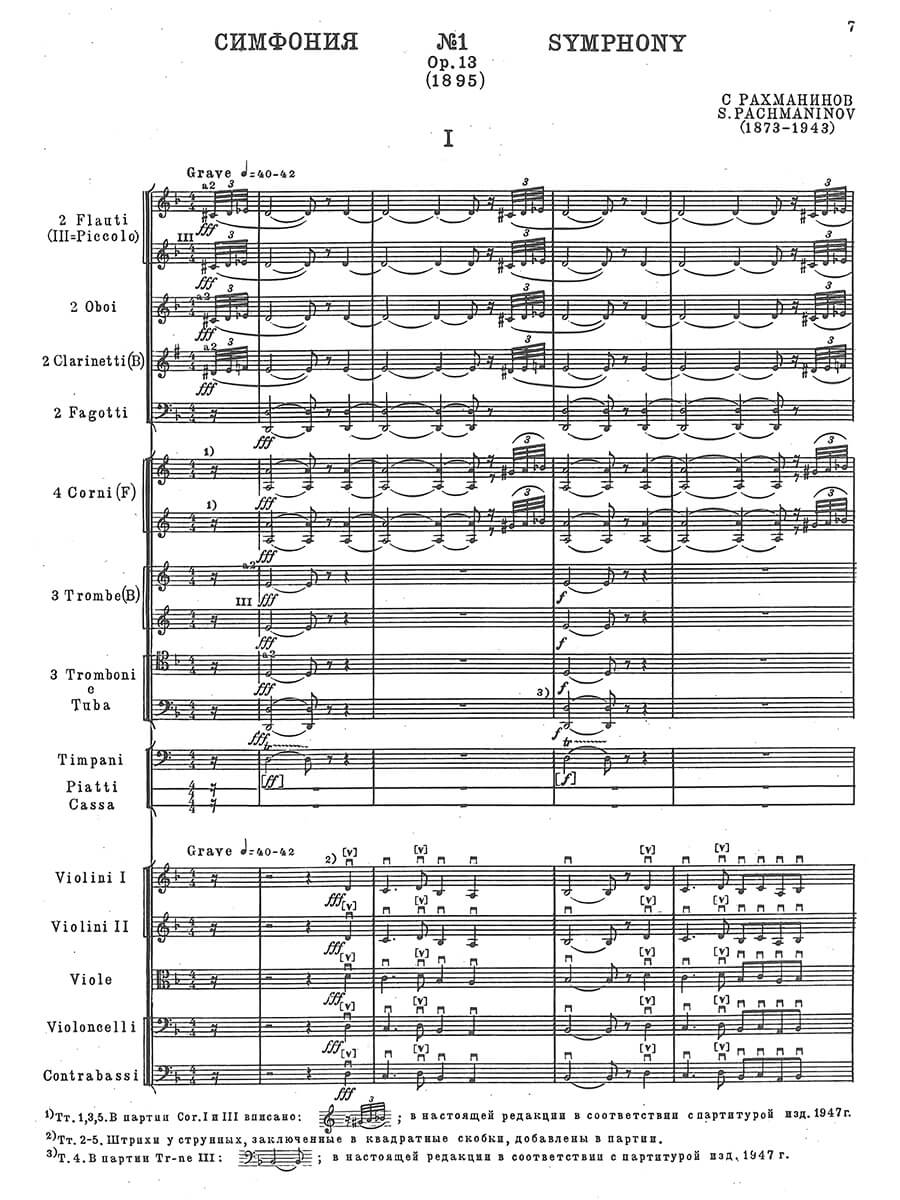

But to return to the symphony as a piece of music: it opens with a fierce ‘motto’, a fortissimo D, ornamented with a long appoggiatura, stated by woodwind and horns. This short motive remains lurking in the background during the whole symphony. Clarinet and strings present the theme of requital, reminiscent of a famous chant. The second theme is of a lyrical type recurring in later works by Rakhmaninov: a large interval upwards, followed by a tortuous descent. The exhibition is marked by a crash (sfff), then a fugato on the main theme ushers in the development. Rakhmaninov builds climax on climax preparing for the recapitulation. The coda ends the movement in ever increasing speed and a last sfff chord from the full orchestra.

The material presented in the first movement is a source of themes for the remaining movements.

Rakhmaninov placed the scherzo as the second movement, as Balakirev and Borodin did. It starts with the motto and followed by a phrase generated by the main theme of the previous movement. Refined triplets as accompaniment abound. In the thirteenth bar of the scherzo we hear a striking motive (two quavers followed by a minim) for the first time.

The slow movement (Larghetto) begins with a repeated forte statement of the motto. Then Rakhmaninov uses the material presented earlier to attain an atmosphere of refinement, interrupted by restrained climaxes.

The D-major finale sets off in a festive mood. Although some quiet passages alternate with loud march-like ones, the movement makes a rather boisterous impression. It is less convincing than the previous three movements. A long, fast, loud coda seems to end the symphony, but then a solo for timpani starts a Largo, in which the motto plays the most important part. It is repeated many times fortissimo together with the motive from the scherzo mentioned above at the very end of the symphony.

This first attempt at a large symphonic work by a young composer has, of course, its shortcomings, but it has much to offer. It shows the path the composer would perhaps have gone if its first performance had been much better rehearsed and better received by the critical press.

Willem Vijvers, 2015

For performance material please contact Boosey & Hawkes, Berlin. Reprint of a copy from the Musikabteilung der Leipziger Städtischen Bibliotheken, Leipzig.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Pages | 288 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |