“Shed” Symphony No. 1 in C arranged for small orchestra from four pieces for wind quintet by Phillip Brookes

Elgar, Edward / arr. Brookes, Phillip

19,00 €

Preface

Edward William Elgar

(b. Lower Broadheath, Worcester, 2 June 1857; d. Worcester, 23 February 1934)

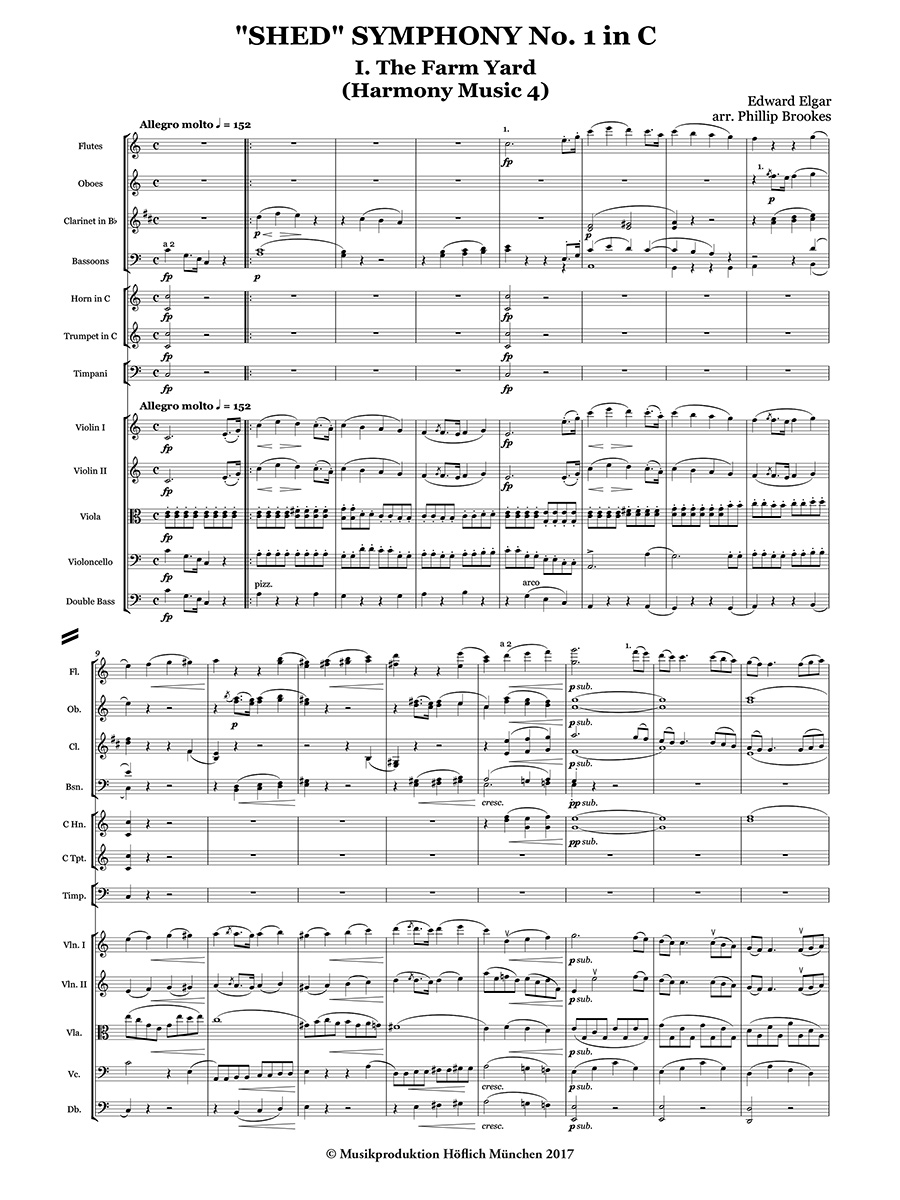

“Shed” Symphony No. 1 in C

arranged for small orchestra

from four pieces for wind quintet by

Phillip Brookes

1.

Harmony Music 4:

The Farm Yard

p.1

2.

Adagio cantabile:

Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup

Presto

Promenade No. 3

p.24

3.

Harmony Music 1

Allegro molto

p.37

Preface

Elgar was one of a small handful of composers who were completely self-taught. True, before the middle of the 18th century, self-taught composers were more numerous because music academies were less common. But even then most were the pupils of eminent performers – organists, violinists or kapellmeisters. Of Elgar’s immediate predecessors, none had less formal training than he did, and only Richard Wagner seems to have combined scant training with great talent. Elgar’s abilities developed naturally out of a childhood and youth surrounded by practical music-making. His father, William Henry Elgar, was a partner in a music shop in Worcester High Street, but even then he earned much of his money by travelling around, tuning the pianos of the wealthy members of society. William played the violin and became a regular in local orchestras, especially in those gathered for the Three Choirs Festival, of which Worcester Cathedral, along with Gloucester and Hereford, was one of the hosts. He also played the organ at St. George’s, the local Catholic church (the family had converted to Catholicism before Edward Elgar’s birth). It is doubtful if William Elgar was a devoted Catholic, however, since he is said to have regularly left the church during the sermon to drink at a local tavern.

It is hardly surprising, then, that young Edward grew up with music. He eventually joined his father as a violinist in the Three Choirs orchestra, and replaced him as the organist at St. George’s. But he never had more than rudimentary lessons on the violin or piano: a natural talent instead began to emerge that was ‘at home’ in the world of practical music-making.

Nothing demonstrates this better than the music he wrote – from April 1878 until 1881 – for himself and a number of friends to play on Sunday afternoons. For most of the time the ensemble was a woodwind quintet consisting of two flutes, oboe, clarinet and bassoon, all played by amateurs of differing abilities: Elgar’s brother Frank (oboe – clearly an outstanding player), Hubert and William Leicester(flute and clarinet), Frank Exton (flute) and Edward Elgar on bassoon. Because the ensemble was an unusual one (a standard wind quintet is flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon) there was no existing repertoire available to play, so Elgar composed or arranged all of it. The ensemble (which later included a violin and cello – Elgar playing the latter) met every Sunday afternoon in a shed behind Elgar Brothers’ music shop, and they called themselves “The Brothers Wind” or “The Sunday Band” and serenaded many locals at rural events. More particularly, Elgar called the music “shed music” and marked the seven volumes with the designations “Shed 1”, Shed 2”, etc. Several of the longer compositions he called “Harmony Music” – an Anglicization of the German “Harmoniemusik”, a serenade for wind instruments.

The group continued for only a short time, possibly because Elgar was appointed bandmaster of the Attendants’ band at Worcester and County Lunatic Asylum at Powick, which brought with it commissions for polkas, quadrilles and the like – for all of which he was paid. But Elgar never forgot his “shed” music, and several pieces eventually found their way into later compositions. The Shed books were in fact preserved by Hubert Leicester and are now in the British Library.

A new Elgar symphony?

Notes on the orchestration.

One thing can be said for certain: Elgar never seems to have considered turning any wind quintets into symphonies. It is nonetheless true that several pieces of Harmony Music are in classical sonata form, showing that the young composer had studied well the scores in his father’s shop and was thinking on a large scale. One work (Harmony Music 5) is actually in classical symphonic form and lasts nearly 28 minutes; it mirrors similar works by Krommer, Hummel, Danzi and others. (Harmony Music 5 will appear eventually in Repertoire Explorer as “Shed” Symphony No. 2.)

The present score is a realization of four individual movements that fit naturally together as a lighthearted ‘symphony’ of the kind that Weber or Gounod might have recognised. The nearest parallel is an interesting one: Bizet’s youthful Symphony in C of 1855 has much of the spirit of this work. Indeed, Elgar’s 1878 work seems to quote the Frenchman’s in at least one of its themes. But this cannot be so, since Bizet’s work was not published until the 1930s and not performed until 1935. Elgar can never have heard it. Perhaps this is an instance of two talented and creative minds of similar ages settling on similar solutions.

The four movements are:

Harmony Music 4:

The Farm Yard

Elgar dated this score 17 September 1878. This cannot realistically be the date of composition, since the work is of more than 350 bars, lasting 12 minutes. It is probably the date on which Elgar completed the score.

It is in sonata form, with the exposition repeated. However, the themes are neither broadly-phrased nor do they fit easily into ‘1st and 2nd subjects’. Rather, there are three groups of short themes. The first consists of two contrasting four-bar figures, one upward-moving, the other downward-falling. They are repeated and extended sequentially and move between C major and A minor. They are quoted in full as nos. 1 and 2 of the attached examples. At figure 2 a new idea is presented in G major (no. 3 of the examples). It lasts just two bars (with many extensions) but becomes very important in the development and it leads to a strong figure with fanfare-like accompaniment (example 4). This in turn heralds the climax of the exposition, the return of example 2, though now in G major. The exposition closes quietly, still in G, with a new and extended group that begins with example 5 and ends with example 3.

The development is concerned mainly with examples 1 and 3, the latter gaining prominence. The recapitulation introduces a new idea (example 6) – a rhythmic, march-like figure accompanied by off-beat thumps in the bass. This was to become such an Elgarian characteristic that it is difficult to hear it in such an early work without breaking into a broad smile. The resulting climax leads to a return of example 2 fortissimo and we might think the end is in sight, but the young Elgar delays it by bringing back examples 5, 3 and 6 to introduce a coda characterized by Schumannesque dotted rhythms and final references to 5, 3 and 6 as the movement ends. Elgar would not encounter Schumann’s music for another five years – he was immediately captivated – so again we may suspect that this is an example of similar creative personalities finding similar solutions independently.

It might be easy to think that Elgar was too inexperienced to create more extended themes and more traditional first and second subjects, but remarkably his two ‘real’ symphonies (the A-flat of 1908 and the E-flat of 1911) employ exactly the same trick. Instead of ‘subjects’ there are subject-groups of short ideas, with new ones being introduced late in the proceedings. Much of the tension is created by developing together individual ideas from separate subject groups – a complex, kaleidoscopic procedure that reinforces any unity underlying the themes. It seems that Elgar already thought this way in 1878, though he lacked the subtlety he would bring to symphonic form as a 50-year-old.

The whole movement reminds me of Weber and I have scored it as if Elgar were using natural horns and trumpets, with just a few exceptions such as the solo two bars before 11, a typical Elgarian falling seventh that seems to me to cry out for the sound of a horn, even though the notes A-flat and B were not available on C horns. (A composer of an earlier age would have given the 1st horn a change of crook (to E) and written E-G, with the 2nd player finishing the phrase with a C played on the C horn. Interestingly, Wagner does just this sort of thing in the Siegfried-Idyll of 1869, though Elgar never used natural horns in anything.)

We do not know why Elgar subtitled the piece The Farm Yard. Presumably it was an in-joke among the players.

Adagio cantabile:

Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup

Presto

Promenade No. 3

These two miniatures provide the slow movement and scherzo, but I have embedded Promenade No. 3 within the Adagio cantabile, rather in the manner of Berwald’s Sinfonie Singulière.

Elgar wrote the Adagio cantabile in June 1878 (2 June was his 21st birthday, but we do not know if there was a connection). The subtitle was the name of a patent medicine for relieving babies’ teething pains and colic. (Its main ingredient was morphine and so presumably worked very well!) Elgar loved word-games, and “Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” was a name that must have appealed to him. Perhaps it indicated the gentle, soothing lilt of the music, for this is a charming movement, simple in form but with enough interest to sustain its duration of more than five minutes. Promenade No. 3 is one of six Elgar wrote; the score is marked 13 August 1878. It is a lively movement in simple ternary form but with a slight thematic resemblance to the Adagio cantabile.

I have not written for natural horns; Elgar’s style here is much more ‘contemporary’, more like that of the music he was soon to write for Powick Asylum. I have reduced the orchestration for these movements, requiring only one flute, oboe and bassoon, pairs of clarinets and horns, and a single cornet (who has a solo in the Trio of the scherzo) in addition to the strings.

Harmony Music 1

Allegro molto

Elgar wrote his first piece for the wind quintet on 4 April 1878 (in this case, he may well have written the work completely on that day – it is very straightforward). He called it Harmony Music 1 and it is a moto perpetuo of great charm. The second subject (fig. 28) sounds almost as if it is a lost tune from a Gilbert & Sullivan opera. The chattering winds throughout bring all four movements to a satisfactory close.

I have written again as if for natural horns and trumpets, since the style of this piece more closely resembles that of the first movement. Thus this final movement uses the same forces as the first.

Phillip Brookes, 2016

For performance material please contact Musikproduktion Höflich (https://musikmph.de), Munich

Score Data

| Special Edition | The Phillip Brookes Collection |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Performance Materials | available |

| Size | 225 x 320 mm |

| Printing | First print |

| Pages | 60 |