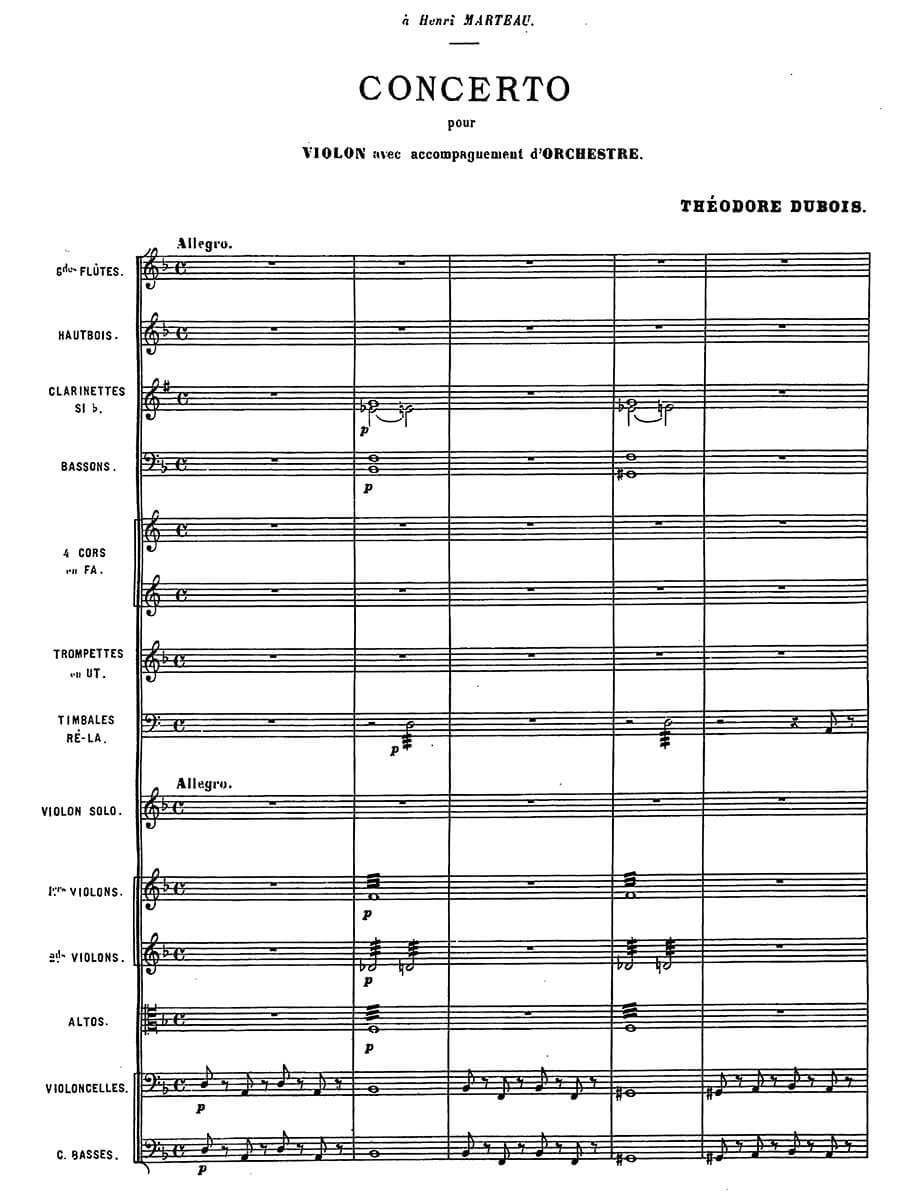

Concerto pour Violin et Orchestre

Dubois, Théodore

29,00 €

Preface

Théodore Dubois -Violin Concerto in D minor

(b. Rosnay, 24 August 1837 – d. Paris, 11 June 1924)

Allegro. p.1

Adagio. p.47

Allegro giocoso p.60

Preface

The life and career of Théodore Dubois follows a path typical of nineteenth-century French musicians: its trajectory embraces composition, teaching and the organ loft. Dubois was born in the village of Rosnay and took his initial musical education from Louis Fanart, the cathedral organist in nearby Rheims. At the age of 16 he enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire; he received tuition in piano, organ, harmony, and counterpoint – this last from Ambroise Thomas. His compositions gained him several first prizes and then, with his cantata Atala, the Prix de Rome in 1861. During his sojourn at the Villa Medici he was given encouragement from Franz Liszt, but on his return to Paris he began to teach and work as an organist, first as maître de chapelle at Ste Clotilde with César Franck at the organ (1863-8) and then in the same position at the Madeleine (1869-1877) after which he replaced Saint-Saëns there as organist. He taught harmony and counterpoint at the Conservatoire from 1871, and later succeeded Thomas as director. In this post he continued his predecessor’s intransigently conservative regime. In 1902 he forbad his students from attending performances of Debussy’s groundbreaking opera Pelléas et Mélisande. He was forced to bring his planned retirement forward in 1905 after a very public scandal involving the faculty’s blatant attempt to prevent another ‘modernist’, Maurice Ravel, from winning the Prix de Rome. His directorship was taken over by Gabriel Fauré.

Dubois is chiefly known in France for his sacred music, notably the oratorio Les sept paroles de Christ (1867), and for his textbooks on harmony, counterpoint and fugue, some of which remain in use to this day. In Anglophone countries he is better known for his charming organ works, in particular the ever-fresh Toccata in G. He was an extraordinarily prolific composer who fostered a desire to conquer the operatic stage. In fact his classically disciplined outlook was much better suited to church music where he composed various masses and at least 70 mostly utilitarian motets. His name is hardly absent from any of the main instrumental genres as well, but barring the organ oeuvre, this body of work is mostly forgotten. A curious footnote to his composition list is an arrangement he made of Bach’s ‘48’ for piano duet.

The virtuosic Violin Concerto dates from 1896 and provides a meaty challenge for the soloist while eschewing any sort of formal experimentation. Classically conceived, the concerto presents idiomatic writing for the violin in music that moves freely between keys while all the time avoiding the shade of Richard Wagner. Apart from the four horns, the accompanying orchestra is the size required for some of Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies written a century earlier. The Violin Concerto was dedicated to Henri Marteau (1874 – 1934), a French virtuoso who later in life took Swedish citizenship.

The first movement begins an orchestral tutti in which several short motifs are presented: the initial subdued march, a more impassioned theme (figure 1) and a declamatory dotted pattern (figure 3). When the soloist enters he presents new motifs more suited to his instrument, most memorable of which is the tender utterance at figure 9. The development (figure 13) mixes treatment of these motifs with rapid passagework. It is perhaps worth remarking that Dubois is quite content to temporarily diverge from a stable tonality in the course of an exposition or recapitulation while keeping the fixed points intact. Thus the recapitulation here starts in D minor with the violinist’s tender theme in D major, but in between these points there are several harmonic diversions. If the first movement overstays its welcome then the same criticism cannot be levelled against its successors. The Adagio in the subdominant key allows a stream of appealing melody to unfurl while keeping strict structural limits in place. Here is Romanticism in Classical form. The final Allegro giocoso permits the soloist to display technical brilliance and emotional lyricism determined by the characteristics of the two main themes. Again there are some surprising tonal detours, but as with the other movements the underpinning structural matrix is never in doubt. A cadenza towards the end makes discreet reference to themes from the previous movements. Although the concerto is well crafted and coherent, it perhaps lacks the melodic distinction and formal imagination necessary to carve out a permanent place for itself in the mainstream repertoire.

Alasdair Jamieson, April 2021

For performance material please contact Heugel, Paris.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Violin & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 104 |