Heroic Overture in C

Büttner, Paul

26,00 €

Preface

Paul Büttner

(b. Dresden, 10 December 1870 – d. Dresden, 15 October 1943)

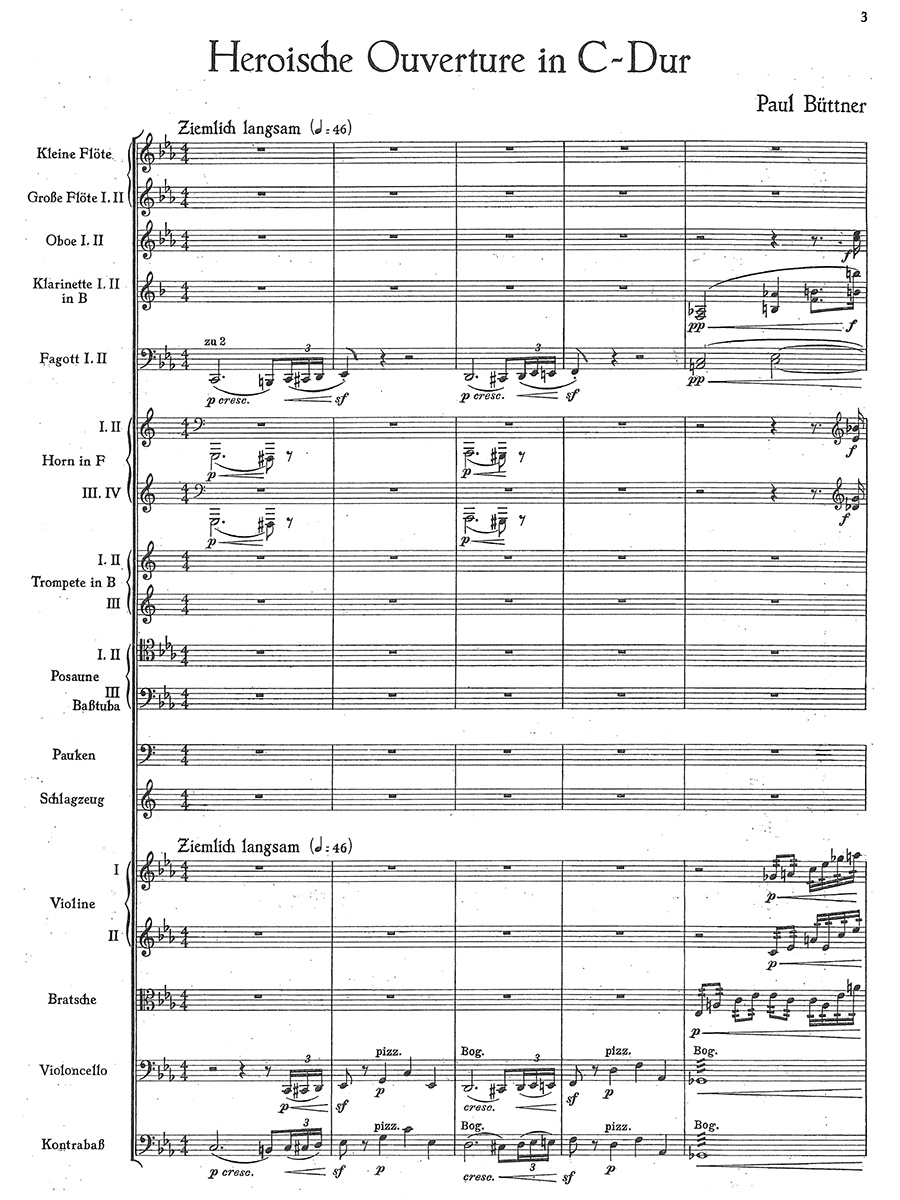

Heroic Overture in C (1925)

Ziemlich langsam (p. 3) – Allegro. Feurig (p. 12) – Ruhiger (p. 19) – Sehr belebt (p. 22) – Moderato (p. 32) –

Allegro (p. 33) – Allegro moderato (p. 41) – Haupttempo (p. 47) – Ziemlich langsam (p. 61) – Haupttempo (p. 64) – Immer ruhiger – Langsam (p. 66) – Haupttempo (p. 68) – Sehr straff (p. 75) – Più mosso (p. 83) – Sehr schnell (p. 86)

Preface

In our day, when new discoveries are made and forgotten or misplaced things unearthed on a daily basis, it seems strange that suddenly a titan should resurface whose greatness stands beyond question at first hearing, and whose music gains in depth, breadth, and grandeur with each repeated listening. That this composer is entirely unknown (I knew of him by name but had never heard any of his works in concert, and only one of his major creations, the Fourth Symphony, has been released on CD, in an historic recording from East Germany), should give us pause. It sheds glaring light on the functioning of a music scene that takes notice of practically nothing outside the most popular names, trends, and fashions. Yet there were times when conservatives considered Paul Büttner the great white hope of the German symphony, when his symphonies and other works were performed by conductors of the stature of Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Busch, Joseph Keilberth, Carl Schuricht, Fritz Stein, Paul Scheinpflug, Hermann Kutzschbach, Paul van Kempen, Rudolf Kempe, Heinz Bongartz, and Rudolf Mauersberger, heading such ensembles as the Dresden Court Orchestra and the Berlin Royal Orchestra (each today called Staatskapelle), the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, or the Berlin RSO. Is it possible for symphonies of such towering significance, having once enraptured large audiences, to be plunged permanently into oblivion? The example of Paul Büttner, one of music’s great “anachronistic” figures, serves as a object-lesson in how changes from favorable to unfavorable circumstances can ensure that this happens not just once but twice. First, in his fifties, he was suddenly thrust into the bright glare of adulation; then, more long-lastingly and less spectacularly, his music was honored and cultivated posthumously by the young state of East Germany, but made practically no impression on the western half of the country on the opposite side of the Iron Curtain, much less elsewhere. For all its quality, splendor, and beauty, Büttner’s music never managed to cross national borders; it remained a German phenomenon in two doomed nation-states, and in each case as part of a doomed culture. Only today do we again recognize in Büttner one of the supreme masters of his generation and a completely natural conduit of the German symphonic tradition from Beethoven and Schubert via Bruckner and Brahms, organically evolving, highly diverse, spaciously modulating, and with inexhaustibly rich and brilliant orchestration, never concerned with effects for their own sake and holding listeners spellbound with its musical imagery. Büttner’s music, though independent in the subtlety of its resources and its transcendent, monumental courage, was never revolutionary. Yet neither does it sound out of date when we hear it today. Its quality is timeless, manifest in infallible skill, and it opens up a limitless universe.

Büttner was born in Dresden into modest circumstances, his father being a peasant from the Ore Mountains. He began taking violin lessons at the age of eight and later studied oboe and viola at Dresden Conservatory. There he soon proved to be the most gifted and profound student in the composition class of Felix Draeseke (1835-1913), where he mastered the composer’s craft in the most thorough and comprehensive way imaginable. It should come as no surprise that Draeseke’s best student would later write such a contrapuntal masterpiece as the Sonata for String Trio, of which the Dresdner Nachrichten had the following to say in 1930: “Six short movements in the form of a canon with inversions in invertible counterpoint – at the 12th! It is one of a kind in the musical literature, the higher mathematics of compositional technique when one reads and analyzes it. Yet the entire piece is a genuine work of art, soaring freely within its self-imposed strictures and sounding so graceful that it was a delight to hear.”

Read full preface > HERE

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 98 |