Trio Sonata for Violin, Viola and Cello (Canons in Inversion in Double Counterpoint at the Twelfth) (Score and parts)

Büttner, Paul

28,00 €

Preface

Paul Büttner – Trio Sonata for Violin, Viola and Cello (Canons in Inversion in Double Counterpoint at the Twelfth)

(b. Dresden, 10 December 1870 – d. Dresden, 15 October 1943)

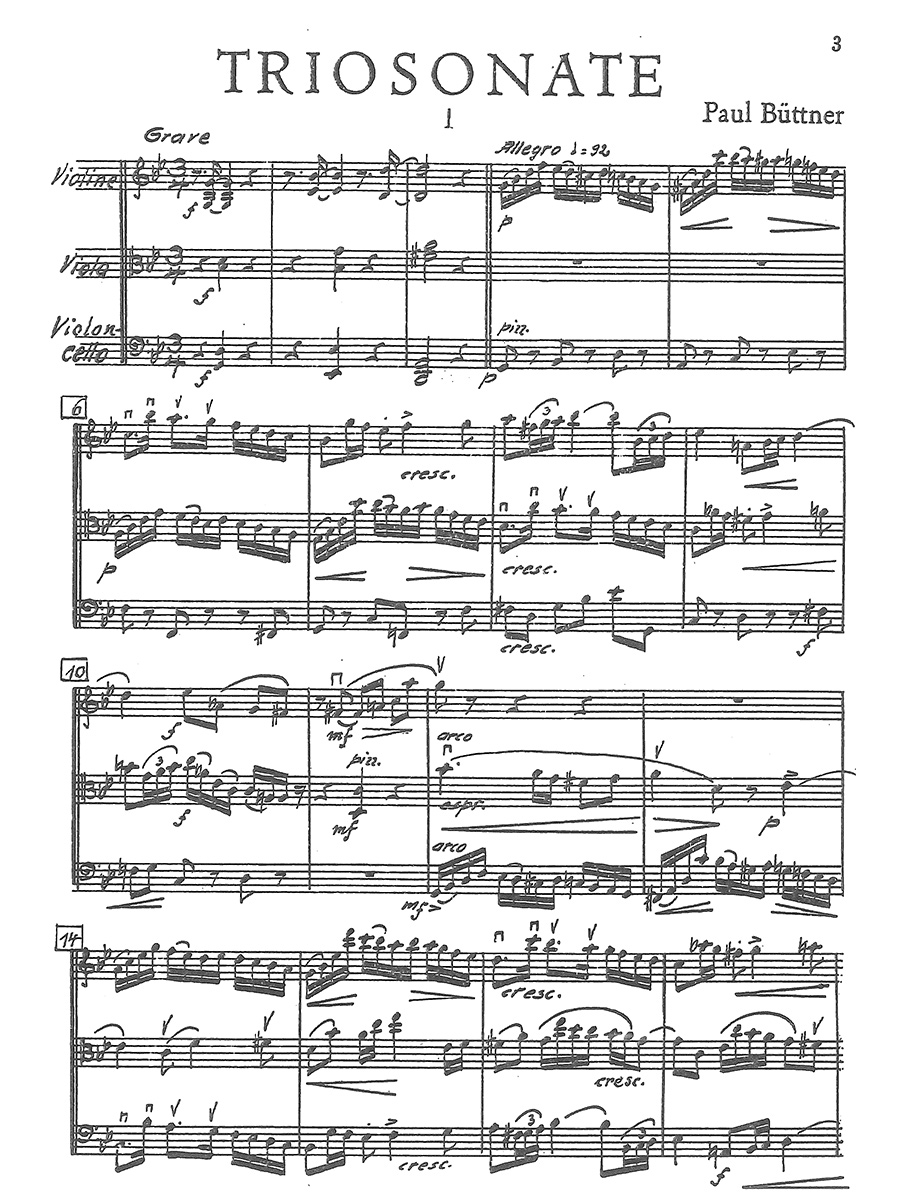

I Grave – Allegro (p. 3) – Grave – Allegro – Grave – Allegro (p. 4) –

Coda. Doppio movimento (p. 5)

II Trio mit Variation (p. 7)

III Adagio sostenuto (p. 8)

IV Vivace (p. 11)

V Andante cantabile (p. 12)

VI Largo (p. 14) –

VII Finale. Presto (p. 15) – Più animato (p. 20)

Preface

In our day, when new discoveries are made and forgotten or misplaced things unearthed on a daily basis, it seems strange that suddenly a titan should resurface whose greatness stands beyond question at first hearing, and whose music gains in depth, breadth, and grandeur with each repeated listening. That this composer is entirely unknown (I knew of him by name but had never heard any of his works in concert, and only one of his major creations, the Fourth Symphony, has been released on CD, in an historic recording from East Germany), should give us pause. It sheds glaring light on the functioning of a music scene that takes notice of practically nothing outside the most popular names, trends, and fashions. Yet there were times when conservatives considered Paul Büttner the great white hope of the German symphony, when his symphonies and other works were performed by conductors of the stature of Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Busch, Joseph Keilberth, Carl Schuricht, Fritz Stein, Paul Scheinpflug, Hermann Kutzschbach, Paul van Kempen, Rudolf Kempe, Heinz Bongartz, and Rudolf Mauersberger, heading such ensembles as the Dresden Court Orchestra and the Berlin Royal Orchestra (each today called Staatskapelle), the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, or the Berlin RSO. Is it possible for symphonies of such towering significance, having once enraptured large audiences, to be plunged permanently into oblivion? The example of Paul Büttner, one of music’s great “anachronistic” figures, serves as a object-lesson in how changes from favorable to unfavorable circumstances can ensure that this happens not just once but twice. First, in his fifties, he was suddenly thrust into the bright glare of adulation; then, more long-lastingly and less spectacularly, his music was honored and cultivated posthumously by the young state of East Germany, but made practically no impression on the western half of the country on the opposite side of the Iron Curtain, much less elsewhere. For all its quality, splendor, and beauty, Büttner’s music never managed to cross national borders; it remained a German phenomenon in two doomed nation-states, and in each case as part of a doomed culture. Only today do we again recognize in Büttner one of the supreme masters of his generation and a completely natural conduit of the German symphonic tradition from Beethoven and Schubert via Bruckner and Brahms, organically evolving, highly diverse, spaciously modulating, and with inexhaustibly rich and brilliant orchestration, never concerned with effects for their own sake and holding listeners spellbound with its musical imagery. Büttner’s music, though independent in the subtlety of its resources and its transcendent, monumental courage, was never revolutionary. Yet neither does it sound out of date when we hear it today. Its quality is timeless, manifest in infallible skill, and it opens up a limitless universe.

Büttner was born in Dresden into modest circumstances, his father being a peasant from the Ore Mountains. He began taking violin lessons at the age of eight and later studied oboe and viola at Dresden Conservatory. There he soon proved to be the most gifted and profound student in the composition class of Felix Draeseke (1835-1913), where he mastered the composer’s craft in the most thorough and comprehensive way imaginable. It should come as no surprise that Draeseke’s best student would later write such a contrapuntal masterpiece as the Sonata for String Trio, of which the Dresdner Nachrichten had the following to say in 1930:

“Six short movements in the form of a canon with inversions in invertible counterpoint – at the 12th! It is one of a kind in the musical literature, the higher mathematics of compositional technique when one reads and analyzes it. Yet the entire piece is a genuine work of art, soaring freely within its self-imposed strictures and sounding so graceful that it was a delight to hear.”

The Dresdner Anzeiger came to a similar conclusion:

“This compositional mastery is displayed to a degree in Büttner’s Sonata for String Trio, which employs, in its structure, the most convoluted and intricate forms of canon imaginable. Yet despite its barely fathomable difficulties, the little piece had an astonishing sound, as if none of this were lurking within it. Indeed, it is a superb example of an art in which technical skill and a comprehensive mastery of form are taken for granted and descend into the realm of givens. What we hear instead is the overall sonic image, which operates within us at the deepest possible level.”

Indeed, the especially striking thing about Büttner’s music is the way in which the most elaborate and time-hallowed contrapuntal devices spring into life and never sound arid or didactic. Rather, they seem to emerge from the given moment in free imaginative flight, and yet form such a convincing unity, whether in the small or in the large, as if it could be no other way.

After completing his studies, Büttner first worked in Bremerhaven as an oboist and viola player, then in Majori near Riga, and from 1892 in the Dresden Gewerbehaus Orchestra. At that time he also began to direct workers’ choruses; to the end of his days he remained a staunch and loyal educator of the working classes, which also found expression in his left-wing stance. In 1896 he was retained to teach choral singing at Dresden Conservatory, where he shortly thereafter also taught music theory. He conducted the Conservatory’s chorus in the great polyphonic literature from Palestrina and Bach to Brahms and Draeseke. He also headed Dresden’s “Eilers Orchestra” and gave concerts with the Gewerbehaus Orchestra, primarily for audiences of workers.

Büttner wrote the first three of his four symphonies – the core of his oeuvre – without any prospect of performance. The First, in F major, was composed in 1898; the Second, in G major, in 1902; and the Third, in D-flat major, in 1910. In 1907 he gave up his position at Dresden Conservatory, partly due to overwork and partly due to internal quarrels. The next ten years were mainly spent conducting his choral societies, including workers’ choruses of up to two-hundred singers. He also regularly conducted the orchestral concerts of the Youth Education Association of the Dresden Workforce, whose programs, all at affordable prices, ranged from the symphonies of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert to Liszt, Draeseke, Busoni, and his own creations. From 1913 his Jewish wife Eva, a professional pianist and art critic for the Dresdner Volkszeitung, helped him to write his program notes and delivered introductory lectures with examples at the piano.

The triumphant success of Büttner’s symphonies began with the première of the Third in 1915. It was followed by prominent repeat performances, the premières of his first two symphonies, and, in 1917, by the composition of his Fourth Symphony, in B minor. It is uncertain why he never composed any symphonies thereafter; no doubt his other activities placed severe demands on his time, and the successes were insufficient to ensure that he could devote himself entirely to composing. In 1918 he resumed teaching at Dresden Conservatory, his courses now expanded to include composition, orchestral conducting, choral conducting, and chamber music. Soon he was also elected the Conservatory’s director. As if that were not enough, beginning in 1922 he wrote high-minded, witty reviews for the Dresdner Volkszeitung as well as various articles and essays, of which Die Kunst zu komponieren (The Art of Composing) deserves special mention. (Some of these writings and most of his compositions are preserved today in the Saxon State and University Library, Dresden.) Büttner’s active life in the public eye lasted fifteen years until 18 May 1933, when, being a Social Democrat and an open opponent of National Socialism, he was dismissed without notice from the directorship of the Conservatory. His works, whose traditionalist leanings would have made them perfectly acceptable to the ideologues of the new régime, were blacklisted. The Dresdner Volkszeitung was likewise banned, which, together with his public ostracism, plunged Büttner’s family into severe financial straits. This was followed by acts of harassment, such as search warrants and confiscations, culminating in the temporary imprisonment of his Jewish wife, a Social Democratic member of the Saxon State Parliament. Büttner devoted the final decade of his life, strength permitting, to writing music and eked out a meager living as a private music teacher. When he died on 15 October 1943 after a year-long illness, his wife became fair game in the city, now “cleansed” of its Jewish population. With the help of a Dresden physician, Dr. Magerstädt, she feigned a case of poisoning and spent the last twenty months of the war hiding in the horse stables of Pulsnitz Castle on a manorial estate owned by Frau von Helldorf. Of all the Jewish musicians who had taken part in the city’s cultural life from 1933 to 1938, expelled from public view, Eva Büttner (1886-1969) was the only one to return after the war. She again became very active in the cultural politics of the Kamenz district, but never did she express herself in public on her experiences during the Third Reich; nor at her death did she leave behind any notes on this terrible period.

In addition to an undated Overture in C major and the Overture in B minor (originally written for the one-act opera Anka), Büttner left behind the following orchestral works, listed here in chronological order: Slavonic Dance and Idyll (1896), Saturnalia for wind band and timpani (1898), First Symphony in F major (1898), Second Symphony in G major (1902), Third Symphony in D-flat major (1910), Fourth Symphony in B minor (1917), Prelude, Fugue and Epilogue: A Vision (1922; first version originally entitled Symphonic Fantasy: War), Heroic Overture for full orchestra (1925), Fugue in C minor (1925), Wind Piece for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, horn and two trumpets (1930) and Konzertstück in G major for violin and orchestra (1937). The bulk of his orchestral music found publishers, but not all of them were actually published; even the Fourth Symphony is available from Peters only in a manuscript in very questionable condition.

Peter Voigt’s catalogue of Büttner’s works lists the following pieces of chamber music: Elegy for violin, cello, harp, flutes and horns (1894); the once popular String Quartet in G minor (1916); two sonatas for violin and piano, one in C minor (1917) and the other in F major (1941); Trio Sonata in the Form of a Canon for string trio (1930); plus the undated works Fantasy-Sonata in G major for violin and piano, Canon-Humoresque (“Katzenmusik”) for three violins with underlaid text by Goethe, and Gedenkblatt for violin or cello and piano. Likewise undated are the fugues, minuets, and Ghasele for solo piano, the latter being a formal idea probably inspired by Felix Draeseke’s piano piece Fata Morgana: Ein Ghaselenkranz, op. 13 (1877).

Besides the one-act opera Anka, Büttner also wrote an operetta Das Wunder der Isis and the fairy-tale opera Rumpelstilzchen. His list of works also includes vocal music without orchestra: eleven men’s choruses, various women’s choruses, trios, lieder, mixed choruses (such as an eight-voice Te Deum), three-part canons on texts by Goethe and Hölderlin, and children’s choruses. The vocal music with orchestra includes six pieces for men’s chorus and orchestra, Recitative with Orchestra for Liszt’s Choral Work “Prometheus Bound” (after Richard Dehmel), Waldesrauschen, and the once highly popular children’s concert Heut und ewig (after Des Knaben Wunderhorn) for solo voice, children’s chorus and orchestra (1905).

By 1915 Büttner, then in his forty-fifth year, had already written three top-caliber full-length symphonies and may well have already embarked on his Fourth. Yet none of these works had been given a hearing. He found himself in a situation of inner necessity to complete these works without receiving any feedback or even acknowledgement from the outside world. It was thus all the more significant that the leading conductor of the age, Arthur Nikisch, decided to take on the Third. On 21 January 1915, fives years after its completion, it was premièred in the fourteenth concert of the Leipzig Gewandhaus, with the Gewandhaus Orchestra headed by its principal conductor Nikisch. Also included on the program were Gustav Mahler’s Urlicht, Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen, and Das irdische Leben, Franz Schubert’s Der Wegweiser and Die Post (from Die Winterreise) as well as Der Erlkönig (all sung by Maria Freund), and, for orchestra alone, Carl Goldmark’s Sakuntala Overture, op. 15. The musicians and the audience were left deeply moved and full of admiration; even the critics went well beyond the standard level of unreserved approval. The word soon spread, leaving a deep mark especially on the reviews of the Berlin première, given by the Royal Court Orchestra in October 1917. Walter Dahms (1887-1973), a critic still valued today for his empathetic biographies of Schubert, Schumann, and Mendelssohn (from 1935 he adopted a second identity in Lisbon under the pseudonym of Gualtério Armando), captured the reverberations of this performance on 19 October 1917:

“Richard Strauss opened this winter’s concert series in the Royal Opera House with a quite extraordinary feat. He handed the baton to the Dresden composer Paul Büttner, who thereupon conducted his Third Symphony in D-flat major for the first time in our city. With joyful satisfaction we note that this composer, who can already look back on a large number of major works, is finally being fêted by the outside world. Germany’s leading orchestras are playing his symphonies, which are greeted with visceral excitement by music connoisseurs everywhere. No wonder, for in these works we can at last hear the longingly awaited natural musican, the composer blessed by God’s grace. No one need complain about the paucity of truly creative talents in our time when men like Paul Büttner live among us and we have the good fortune, as in this case, to savor their creations. In short, Paul Büttner is a master, and his D-flat major Symphony a masterpiece for anyone whose soul is still receptive to the mighty language of genius. He leads us from the nether regions of everyday life to the heights of festive experience. The prospect is limitless, the mood that penetrates us solemn and sublime. What distinguishes Büttner from so many other composers of today is the intrinsic verity of his music, its overflowing wealth of inspiration, its tension, vehemence, buoyancy, and lilt, the grandeur of its ideas. Here far-reaching arcs of melody are constructed, and the iron rhythms have the unbroken primeval strength of a force majeur. This new master is rooted in Schubert and Bruckner. He is just as powerful and lovely as they; his imagination is, like theirs, of inexhaustible richness; and the melodies that he lavishes upon us bare the mystic emblem of a man born to the eternal. And like all the great masters of music, he loves to construct his melodies on the steps of the triad. From them he chisels out motifs that embody the sublime with their majestic progressions of a 5th, and then coaxes melodies of infinite longing and sweetness from the very same triads. No groping, no seeking, no toying with gimmickry: just the sure assured touch of the self-confident master. Perhaps someone or another will say that Büttner’s melodies are ‘too simple.’ To them we shall reply that all grandeur seems simple. Büttner, too, will discover that stupidity and presumption will cavil at him. But a benevolent Fate has given him a firm staff with which to travel the difficult path to Parnassus: the great and passionate soul of an artist who is granted to pronounce in sound the things that cause joy and pain in the human heart. In short: genius.

“Büttner was uproariously celebrated in the noonday concert. The Royal Orchestra played his work with enthusiasm. It was an experience that shall ever remain in our memory.”

The reviewer of Vorwärts, a certain “S,” drew the following conclusion from the same concert:

“It was one of the few truly great and lasting events of our overly saturated musical goings-on in Berlin. […] The D-flat major Symphony reveals a maturity and originality of inspiration, an enchanting feast of sound in the multi-colored treatment of the orchestra, a consistency in the development of the themes, that make this work from first note to last one of the most riveting of all recent symphonies. We acknowledge with satisfaction that Büttner commands his own striking and strongly independent style that marvelously unites the sublime and the meditative, the dramatic and the lyrical. The ideals of an ardent soul, a tempestuous will, and intimate sensitivity find their finest embodiment in this masterpiece. We are seized in our innermost being by the ruthless truthfulness of expression and the power of conviction that speaks to us from Büttner’s music. […] We welcome him today as the long-awaited composer who restores to our age the pure and exhilarating experience of lofty art brought forth from the deepest reaches of the heart.”

Elsewhere the same “S” discusses the unexpected series of triumphs undergone by Büttner’s music since the première of the Third Symphony under Nikisch:

“Büttner, who arose from the most modest of circumstances, and who has savored the musician’s lot to the last draught, is unconcerned with the aesthetic and fashionable demands of our time. His music is the language of the heart. To quote his own plain words, ‘I do not wish to talk about the idea which was given to me for the D-flat major Symphony, and which, as a loyal servant, I have clothed in the purest form at my command. May the symphony itself speak to the soul.’ […]

“Like all great men, Paul Büttner has had to practice the virtue of being able to wait. The score of his First Symphony had to lay on his writing desk for eighteen years before it received a hearing. Since then a large number of significant creations have flowed from his pen. Now the ice has been broken. Germany’s foremost artistic institutions – the Royal Orchestras of Dresden and Berlin, the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig – have take up the cause of his symphonies. And everywhere the enthusiasm of truly receptive listeners has been the same: overwhelming. The composer, soon to turn fifty, now has the satisfaction of being revered by the very best.”

Eugen Schmitz, writing an appreciation for Büttner’s sixtieth birthday on 10 December 1930, specially singled out the four symphonies and the G-minor String Quartet:

“None of Büttner’s five masterpieces relate in any essential way to the musical currents of our century. Not the program music of the Richard Strauss circle, still less the fashion for atonality, already in the process of vanishing from sight. Büttner, like Brahms and Reger, is a musician who creates ‘against’ his age. At most the details of his technique – his very bold and distinctive (but always strictly tonal) harmonies and his orchestration, a synthesis of Bruckner and Richard Strauss – might lead us to guess, if we did not already know it, that Büttner’s music was written in the twentieth century.”

Büttner’s Trio Sonata, scored for a classical string trio, is one of the few large-scale compositions he was able to complete after the mid-1920s. Expressly subtitled “Canons in inversion in double counterpoint at the twelfth,” it was premièred at the Dresden Tonkünstlerverein on 10 December 1935 – or so we are informed by the archives of the Dresden Staatskapelle. But the small brochure issued by the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party for Büttner’s eightieth birthday quotes three reviews dating from the year 1930. The Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten wrote that everything about the work “sounds so graceful and natural that the exquisite craftsmanship is not even noticeable.” The critic of the Dresdner Nachrichten called it “unique in the literature, higher mathematics of compositional technique when analyzed on the page. Yet the entire piece is a genuine work of art that moves freely within its self-imposed form and sounds so graceful that listening to it was sheer delight.” These views were seconded by the Dresdner Anzeiger:

“This compositional mastery came especially to the fore in Büttner’s Sonata for String Trio, which is constructed in the most convoluted and intricate forms of canon imaginable. Yet despite these almost unfathomable difficulties the little piece has an astonishing beauty of sound, as if nothing of this lay concealed within it. Indeed, it is a fine example of an art in which technical skill and consummate command of form are taken for granted and relegated to the level of prerequisites in favor of an overall sound that wells up within us and moves us to the quick.”

Writing in the Dresdner Anzeiger, Georg Striegler commented on a later performance (perhaps in 1935):

“The high stature that Büttner has attained as a creator of chamber music was further enhanced by Gerhard Schneider, Hans Franke, and Fritz Sommer’s performance of his String Trio in Canonic Form. Here the artful texture was laid out to masterly effect. The ‘double counterpoint at the twelfth’ blossomed with a radiance not without impact on the emotions. This merit was manifest to a high degree in the slow sections. The humor of the canonic rendition of Rumpelstiltsken’s song ‘Ei, wie gut, dass niemand weiss’ [‘For little knows my royal dame that Rumpelstiltskin is my name!’] was delectable.”

Büttner’s Trio Sonata for violin, viola, and cello did not appear in print until 1960, when it was published by Peters of Leipzig in their Collection Litolff. Our volume is a faithful reproduction of that first edition.

Christoph Schlüren, January 2016

For performance material please contact Musikproduktion Höflich (www.musikmph.de), Munich.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Chamber Music |

| Pages | 64 |

| Size | 225 x 320 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Specifics | Set Score & Parts |