Concerto for Clarinet, Viola and Orchestra Op. 88

Bruch, Max

25,00 €

Preface

Max Christian Friedrich Bruch

Double Concerto in E minor for clarinet or violin and viola with orchestra, op. 88

January 6, 1838 (Cologne (Köln), Rheinprovinz, Königreich Preußen) – October 20, 1920 (Friedenau)

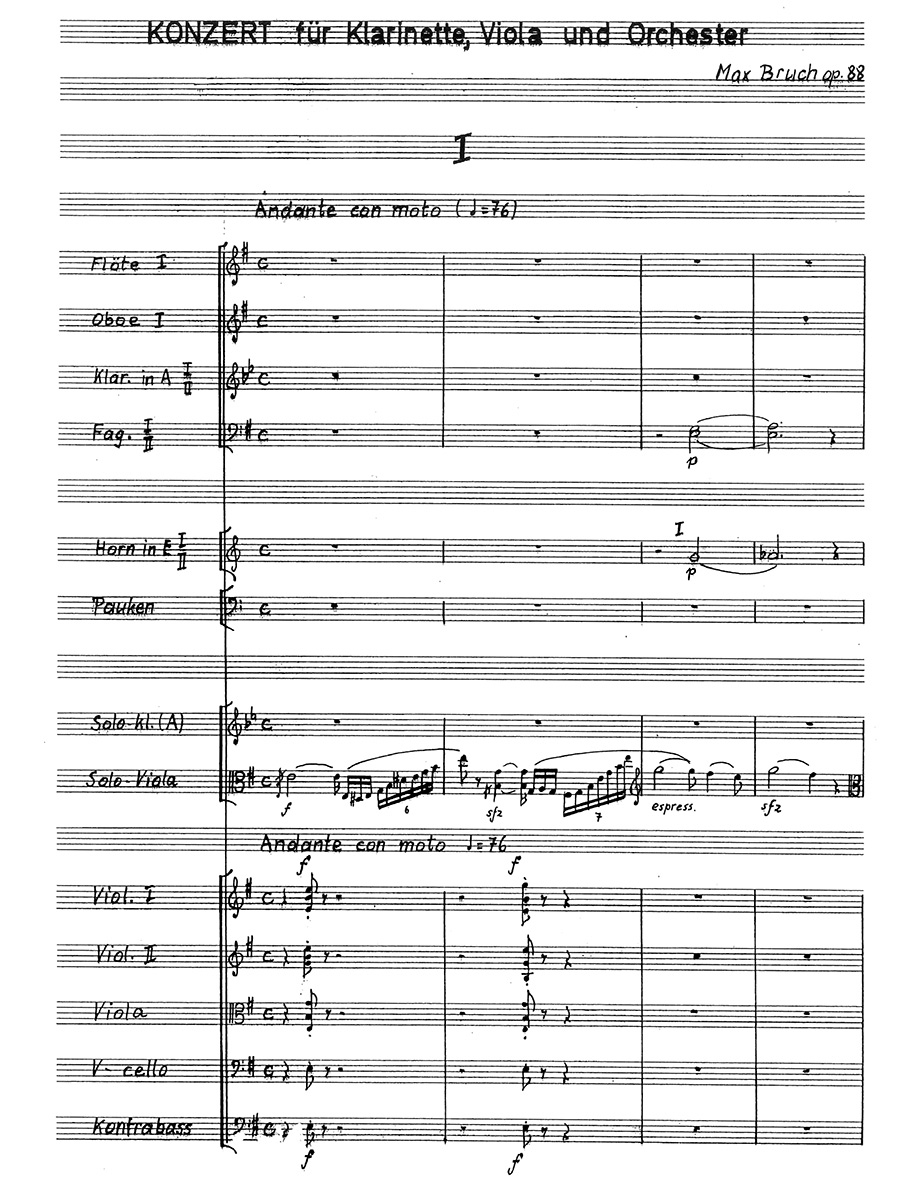

I. Andante con moto p.1

II. Allegro moderato p.18

III. Allegro molto p.38

Date Of Composition

1911

First Publications

Berlin, Rudolf Eichmann [the successor to Simrock], 1942

Dedicated to the composer’s son, the clarinetist Max Felix Bruch

First Performances (performing from the manuscript)

5 March 1912 at the seaport in Wilhelmshaven, Germany

3 December 1913 at the Hochschule für Musik, Berlin

Max Felix Bruch, clarinet solo, and Prof. Willy Hess, viola solo

Preface

Max Bruch was a German composer who wrote over 200 works, notably his moving Kol nidrei for cello and orchestra, op. 47, and the first of his three violin concertos (Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26, 1866), which has become a staple of the violin repertory. Although he was raised Rhenish-Catholic, the National Socialist party banned his music from 1933-1945 due to his name, his well-known setting of a melody from the Jewish Yom Kippur service, and his unpublished Drei Hebräische Gesange for mixed chorus and orchestra (1888). As an adult, Bruch was Protestant, and was the grandson of the famous evangelical cleric Dr. Phil. Christian Gottlieb Bruch (1771-1836).

Bruch was also an accomplished teacher of music composition from 1892-1911, conducting seminars and ensembles at the Royal Academy of Arts at Berlin (Königliche Akademie der Künste zu Berlin). British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams studied with Bruch, describing him as a proud and sensitive man. Bruch actively resisted the Lisztian/Wagnerian musical trends of time, and modeled his works on those of Mendelssohn and Schumann. His concerti share structural characteristics with Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor, omitting the first movement exposition and linking multiple movements. His most lasting contributions to chamber music include works written for his son Max, who was a clarinetist.

Child Of His Time

Bruch was born in the same decade as Johannes Brahms, Georges Bizet, and four of the Russian Five or “Mighty Handful” (Могучая кучка). At the age of fourteen (1852), he was awarded the Mozart Prize of the Frankfurt-based Mozart Stiftung, which enabled him to study with virtuoso Ferdinand Hiller. In 1858, he moved on to Leipzig and then held posts in Mannheim (1862-1864), Koblenz (1865-1867), and Sondershausen (1867-1870).

Beginning in his early twenties, he received commissions for chorus, orchestra, and soprano solo such as Jubilate Amen, op. 3 (1858) and Die Birken und die Erlen, op. 8 (1859). Max Bruch followed Hiller’s advice, and planned to travel to Leipzig in early 1858. With its famous Conservatory, the Gewandhaus Orchestra, and its internationally respected music publishers such as Senf, Kistner, and Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig was a center of considerable significance. Although the Gewandhaus was under the direction of Julius Rietz at this time, the influence of Mendelssohn and Schumann still dominated the musical life of the city.

After his arrival in Leipzig, the young composer befriended Ferdinand David, leader of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, soloist in the first performance of Mendelssohn’s violin concerto, and teacher of Joachim. The friendship led to David and his colleague, Friedrich Grützmacher, the principal cellist of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, playing the first performance and receiving the dedication of Bruch’s Piano Trio, op. 5.

Breitkpof & Härtel took Bruch on as a composer; they published his Opp. 3-5, 7-15 and 17 during the next five years. His Violin Concerto in G Minor was composed in 1866 and substantially revised and programmed by Joachim, assuring its success.

Major Works

During his lifetime, Bruch was renowned for his large-scale oratorios, most of them inspired by the Prussian political activity that led to Germany’s unification (1871), and of which Bruch was an eager supporter. His oratorio subjects focused on national leaders as role models (the Greeks Odysseus and Achilles, the Germans Arminius and Gustav Adolf, and the biblical Moses).

The highpoint of this period coincided with Bruch accepting a position in Berlin in 1870. Here, he wrote the two women’s cantatas of op. 31 (1870, Die Flucht nach Egypten and Morgenstunde); Normannenzug, op. 32 (setting a balled by J. V. von Scheffel, unison male voices and baritone soloist, 1870); three mass movements, op. 35 (Kyrie, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, 1870) for two soprano soloists and mixed chorus with orchestra; the full-length oratorio Das Lied von der Glocke, op. 45 (after Schiller, 1872), and his greatest success in Berlin, Odysseus: Szenen aus der Odyssee, op. 41 (written for soloists and mixed chorus to a text by W. P. Graff, 1872).

He held several prestigious positions, directing the Liverpool Philharmonic (1880-1883) and leading notable concerts in Berlin and northern German cities. He went on an American tour and directed singing societies. He continued to compose for men’s chorus (Kriegsgesang, op. 63 and Leonidas, op. 66, 1894-1896) and for mixed chorus (over twenty more works in German dating from the 1870s through his last choral work in 1919: Trauerfeier für Mignon, op. 93 (after Goethe).

Bruch And The Clarinet

Like Brahms, Bruch came to the clarinet late in life. Bruch was in his seventies and nearing retirement from his post on the faculty of the prestigious Berlin Hochschule für Musik when he wrote his Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano, op. 83*, followed soon after by his double Double Concerto for Clarinet and Viola, op. 88. Both Bruch and Brahms usually wrote for the A Clarinet (rather than the B-flat), due to its richer tone. And like Brahms – and Mozart before – Bruch was inspired to write his clarinet works by one unusually gifted clarinetist: Brahms and his contemporaries worked with Richard Mühlfeld (1856–1907) of the Meiningen Court Orchestra, and Bruch collaborated with his own twenty-five-year-old son, Max Felix Bruch (1884-1943), who had just started his career as a professional performer and conductor in Hamburg. Trained by his father at the Hochschule in Berlin, Max Felix later became the German representative of International Gramophone Company.

Double Concerto

Opus 88 offers an intimate conversation between two alto instruments. This tunefully rich and opulently romantic composition quotes from Bruch’s earlier melodies and folk structures drawn from his early suites. The composer was seventy-three when it was first performed in 1911 to an audience more sympathetic with the modernist experimentation; the premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps exploded on the Parisian concert scene only two months after the Double Concerto’s premiere. The Allgemeine Musikzeitung (No. 50, 1913) described the work as “harmless, weak, unexciting, first and most of all too restrained, its effect is unoriginal and it shows no masterstrokes.” For a self-described “traditionalist” composer and composition professor who championed the chamber music of Mendelssohn and the elegance of late German Romanticism, this critic had missed the point of the work.

Bruch hoped both of his late works featuring the clarinet would be heard as consistent with the style of his well known and much-played Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor from over fifty years before. Until the end of his career, Bruch uncompromisingly defended his Romantic appreciation of art, and this attitude led to controversial discussions with some of the most eminent composers of his time, including Wagner, Liszt, Reger, and especially Richard Strauss, who allowed Bruch’s music to be banned in Germany during the early 1940s.

Bruch’s ingenious, but subtle orchestration progresses from fourteen to twenty-one accompanying voices through the three movements, finally boasting a full complement of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, strings and percussion. The composer provided an alternative scoring for violin (replacing the clarinet) and a piano reduction, continuing his practice of adapting his large-scale works as chamber music.

The concerto’s form is also unusual, as it begins with a relatively slow movement featuring cascading arpeggios, proceeds to a somewhat faster one, and ends with a vigorous triplet-powered Allegro molto. The most dramatic passages appear at the very beginning, as the viola and then the clarinet introduce themselves: Bruch meant this to echo the structure of the cello and violin entrances in Brahms’ Double Concerto. The second theme in the second movement quotes the first movement of Bruch’s Suite No. 2 for Orchestra (Nordland Suite, 1906, WoO).

Bruch’s son premiered the work in 1912 with Prof. Willy Hess, a German violin virtuoso and professor of violin and viola at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik. Hess was a principal student of Joseph Joachim, an outstanding virtuoso and early colleague of Bruch. From 1904-1910, Hess was the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but returned to Berlin at Bruch’s request in 1910 to become the premier violin instructor at the Hochschule für Musik. He consulted on the string writing for all of Bruch’s late scores, also premiering his Concert Piece for Violin and Orchestra, op. 84. During the Weimar Republic, he became associated with many modernist musical luminaries and the Berlin Hochschule became a hub of the international music scene.

Publications And Resources

Universitäts-und Stadtbibliothek Köln holds the autograph of this work on microfiche. The original autograph was thought to be lost, but reappeared in a London auction in 1991 and is now held by the Max Bruch Archiv in the Musicology Department at the University of Cologne. The autographs of Bruch’s piano reduction and the solo parts are still considered to be lost. Many more of Bruch’s autograph scores, letters, and photographs form part of the Zanders family archive housed in the Villa Zanders in the center of Bergisch Gladbach. These materials were presented to Maria Zanders and her family as a token of Bruch’s gratitude for the continued use of his summer retreat Igeler Hof.

The editor of the first edition of the full score, Otto Lindemann, made significant changes in Bruch’s manuscript himself with a green pencil: these alterations survived in the printed editions of both the orchestra score as well as the piano reduction. Since for many years it was not possible to buy or rent performance materials for this work, clarinetist Nicolai Pfeffer developed revised orchestral parts, a new Urtext edition of the score (2010) and a new piano reduction (2008) by comparing the autograph score with the original 1942 printing: these are available from Edition Peters. Oliver Seely also edited a new version of the full score in 2011. Christopher Fifield’s Max Bruch: His Life and Works (Boydell, 1988, reissued 2005) is the only full-length documentary biography of Bruch; it includes musical analyses in English of all of his published works, including all of his concertos, three German operas and several oratorios. This is the best source for a discussion of Bruch’s letters and other contemporary sources that support his place in the vibrant musical culture of his time. The detailed biography Richard Mühlfeld: The Brahms Clarinetist (Balve: Artivo Music Publishing, 2007) by Maren Goltz, Herta Müller, and Christian Mühlfeld provides rich detail about the role of the clarinet in German Romantic music.

©2016 Laura Stanfield Prichard, San Francisco Symphony

*Acht Stücke für Klarinette, Bratsche und Klavier oder Violine, Violoncelle und Klavier, Badin/Leipzig: N. Simrock, 1910. First published in eight separate booklets.

For performance material please contact Simrock, Berlin.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Pages | 86 |