Serenade for violin and orchestra Op. 75

Bruch, Max

33,00 €

Preface

Max Bruch

Serenade in A minor for Violin and Orchestra, op. 75

(b. Cologne, 6 January 1838 – d. Friedenau near Berlin, 2 October 1920)

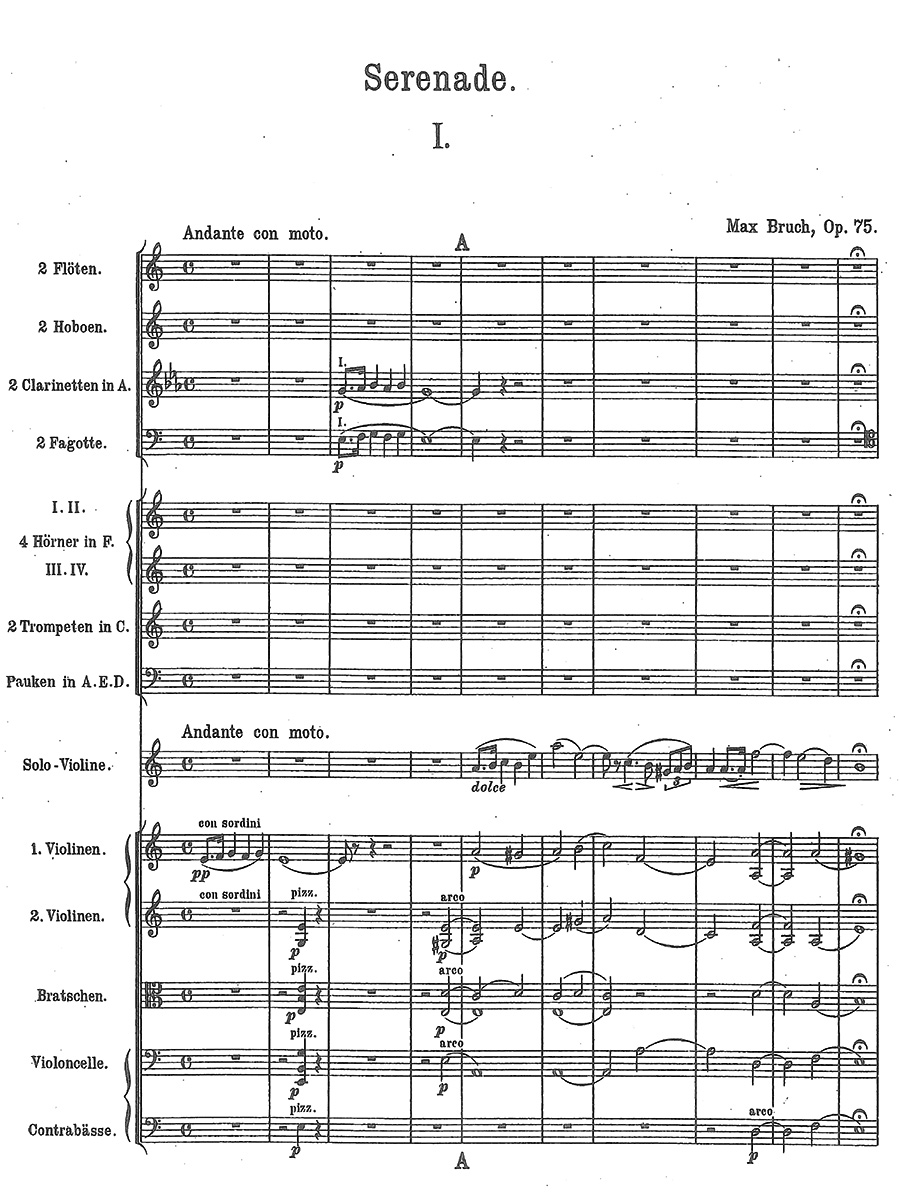

1. Andante con moto p.3

2. Allegro moderato, alla marcia p.30

3. Notturno p.74

4. Allegro energico e vivace p.92

Preface

Besides vocal music, for which he expressed a preference during his student years, and which makes up a large part of his oeuvre, Max Bruch also had a strong predilection for the violin. His catalogue contains no fewer than nine single- or multi-movement works for solo violin and orchestra, including three concertos expressly labeled as such. Judging from his own statements, what attracted him to the instrument was its closeness to the human voice and its resultant affinity for melody – a fundamental aesthetic precept from a man who once referred to melody as “the soul of music.”1 His Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26, has remained in the standard repertoire of violinists the world over and is regularly heard in concert. In contrast, his other works have always stood in the shadow of the First Concerto and gradually fell into oblivion after his death.

This was the fate that befell the Serenade in A minor for Violin and Orchestra, op. 75. It was composed in summer 1899, partly at the Igel farmstead near Bergisch Gladbach2 – a place to which the composer felt a lifelong attachment and where he often fled for rest and relaxation. The outside movements frame a march-like second movement and a melancholy slow movement called a Notturno. An essential component of the opening movement is a freely adapted Nordic melody3 that recurs in the finale. In every movement the solo part captivates with its vein of elegance, and for large sections at a time its graceful and melodious character seems tailor-made for the violin. This is especially true of the opening movement and the Notturno, where Bruch’s distinctive voice, with its proximity to vocal music, comes especially to the fore in the lyrical passages. Similarly, the warm orchestral sound – a typical feature of Bruch’s orchestration – is reflected throughout the piece.

As in his earlier works for violin and orchestra, Bruch drew upon the expertise of a violinist for the Serenade. Joseph Joachim, who had already advised Bruch in his First and Third Violin Concertos (opp. 26 and 58, respectively), had a hand in marking up the solo part. Joachim’s involvement is surprising in that the composer actually wrote the piece for the Spanish virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate.4 However, to his disappointment, Sarasate lost interest in the Serenade after his initial enthusiasm, which led to a profound breach between the two artists.5

Owing to its four-movement design, the Serenade bears an interesting resemblance to the Scottish Fantasy in E-flat major for violin and orchestra, composed twenty years earlier (op. 46). And as in the Fantasy, it harbors a problem which the composer, a man beholden to the classical-romantic tradition to the end of his days, faced when it came to choosing a title: the four-movement design departed from the three-movement pattern established for the concerto in the eighteenth century and followed by the vast majority of concertos in the nineteenth. Considering his other pieces for violin and orchestra, we immediately notice that works laid out in the traditional three movements (opp. 26, 44, and 58) are invariably called “concertos,” suggesting that Bruch had a conservative approach to this generic term. This conservatism is particularly noticeable in the fact that for a while he considered applying the “concerto” tag to both the Scottish Fantasy and the Serenade only to reject it in the end.6 In a letter of 17 February 1911 to his publisher Fritz Simrock, he directly addresses the problem of formal design in connection with his two-movement Concert Piece in F-sharp minor for violin and orchestra (op. 84), which may retrospectively explain his reluctance to apply the term to the Serenade and the Scottish Fantasy:

“I cannot choose this title

By choosing the titles Serenade and Fantasy as free forms, Bruch thus avoided the conflict with the genre’s tradition and manifested his own formal aesthetic standards, rooted in the classical-romantic ethos. Even so, contemporary writers regarded both the Scottish Fantasy and the Serenade as violin concertos.8

The Serenade received its first hearing during an orchestra class at the Berlin Musikhochschule in December 1899, with the composer conducting and Joachim taking the solo part.9 Two months later the piece was ready to be engraved,10 and it was duly published by Simrock of Berlin in 1900. This first edition has served as the basis of the present reprint.

The official première was given in Paris by Belgian violinist Joseph Débroux on 15 May 1901, with Camille Chevillard conducting the Orchestre Lamoureux.11 Other performances followed in Cologne and Berlin; inquiries from England and performances in the USA bear witness to a thoroughly successful initial reception.12 In the end, however, the Serenade shared the fate of most of Bruch’s works and “suffered” from the fame of his First Violin Concerto. If the critics’ response already tended to be mixed, the Serenade was invariably measured against the G-minor Concerto and found wanting13 – a fact that left the composer deeply offended and embittered. Moreover, compared to the modernist and avant-garde currents of the fin de siècle, Bruch’s romantic idiom seemed reactionary and became the target of violent vitriol. That the bulk of his music has fallen by the wayside is an indirect consequence of these trends.

If the rejection of Bruch’s works in his own day may have been caused by his adherence to outdated aesthetic views, our detached twenty-first-century vantage point gives us an opportunity to rediscover and revaluate his music. The present edition in full score is intended help this endeavor.

Translation: Bradford Robinson

1 Arthur M. Abell: Gespräche mit berühmten Komponisten, 7th edn. (Haslach: Artha, n.d.), p. 160.

2 Christopher Fifield: Max Bruch: Biographie eines Komponisten (Zurich: Schweizer Verlagshaus, 1990), p. 94.

3 Ibid., p. 270.

4 Karl Gustav Fellerer: Max Bruch (Cologne: Volk, 1974), p. 138.

5 Ibid.

6 Wilhelm Lauth: Max Bruchs Instrumentalmusik (Cologne: Volk, 1967), pp. 93 and 98.

7 Letter to Simrock, dated 17 February 1911, quoted from Wilhelm Altmann: “Max Bruch’s Beziehungen zu dem Verlag N. Simrock,” Erich H. Müller, ed.: Simrock-Jahrbuch I (Berlin: Simrock, 1928), p. 105.

8 Ibid., pp. 96f. and 105.

9 Letter to Simrock, dated 5 November 1899, quoted from Fifield, Bruch (see note 2), p. 270.

10 Fellerer, Bruch (see note 3), p. 138.

11 Fifield, Bruch (see note 2), p. 272.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

For performance material please contact Simrock, Berlin.

Score Data

| Score No. | 1816 |

|---|---|

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

| Genre | Violin & Orchestra |

| Pages | 150 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Printing | Reprint |