Complete String Quartets Nos. 1-3 / Critically revised Urtext edition by Lucian Beschiu (Score)

Arriaga, Juan Crisóstomo de

25,00 €

Preface

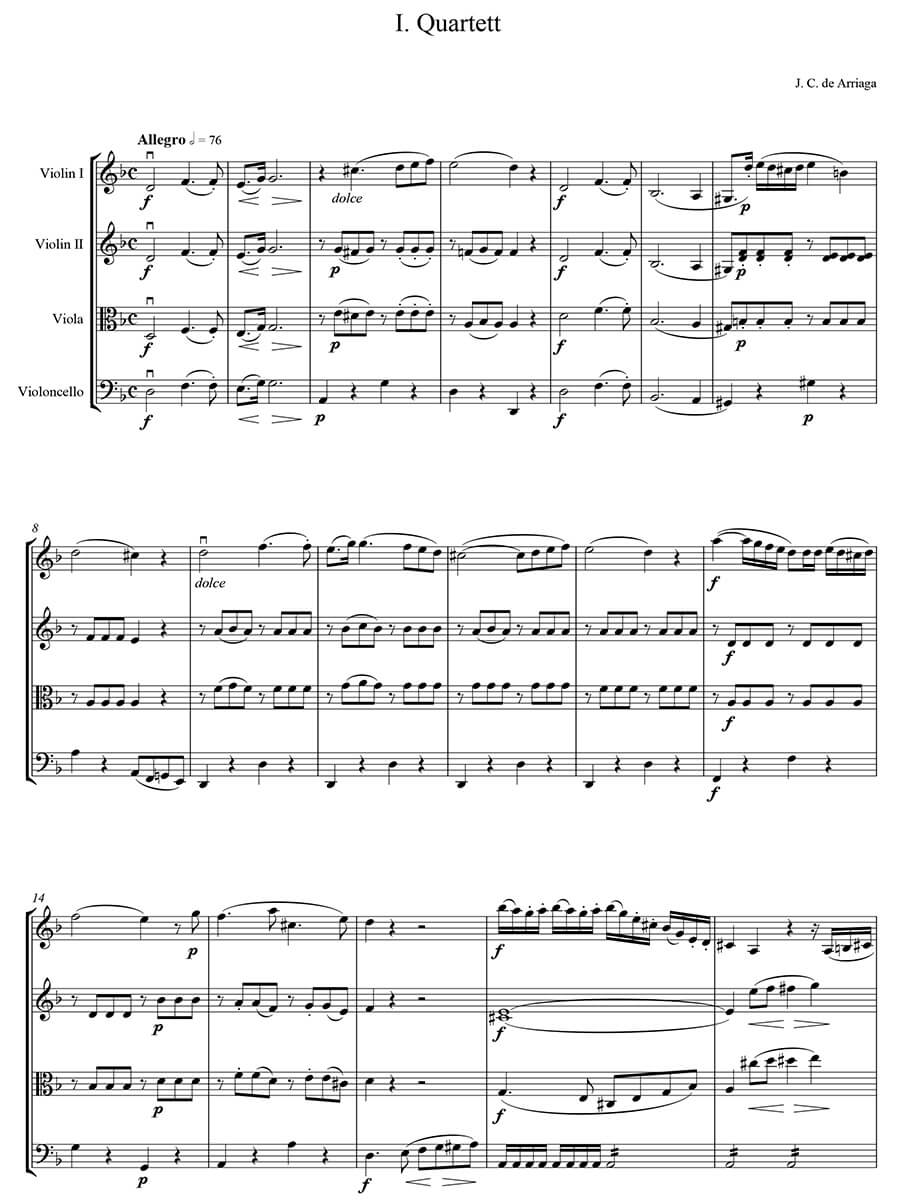

Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga – Troi quatuors pour deux violons, alto et violoncelle (1824)

(b. Bilbao, 27 January 1806 – d. Paris, 17 January 1826)

Preface

Of all the boy-geniuses who graced the history of music only to be cut down before their great talents could unfold, Juan Crisóstomo (Jacobo Antonio) de Arriaga (y Balzola) is surely one of the most tragic. Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schumann, and Wolf all left behind enough music that historians can, as they love to do, safely divide it into early, middle, and late periods; Pergolesi and perhaps even Guillaume Lekeu, despite their brief lives (twenty-six and twenty-four years, respectively), left behind works that have never lacked for champions. But Arriaga, after a brilliant boyhood, died ten days before reaching his twentieth birthday, and his many works were dispersed and in many cases irretrievably lost before their value could be fully assessed. What we have left is a slender body of music rich in unfulfilled promise and, in two cases, serious candidates for admission to the standard repertoire: his Symphony in D (1821-26) and the present Three String Quartets (1824).

Arriaga came from a wealthy Basque mercantile family in Bilbao. His father was a trained musician who encouraged his son’s extraordinary talents to the extent that this was possible in the musical backwaters of that provincial capital. By the age of twelve Juan had already composed a number of works, of which two survive: Nada y mucho, an octet for five strings, trumpet, piano, and guitar (Manuel de Falla, when shown its belated publication of 1929, pronounced it a “prodigy in the history of music”), and an Overture (Nonet), proudly called “op. 1,” for four strings, two trumpets, two clarinets, and flute. By far the most impressive work of these childhood years was, however, a two-act opera semi-seria entitled Los esclavos felices, composed at the age of thirteen and performed to much local acclaim in Bilbao one year later (1820). On the strength of these early successes, the young genius was sent to Paris by his family to study at the Conservatoire.

Arriaga arrived in Paris in 1821, armed with his most recent Bilbao composition, a Stabat mater for three voices and small orchestra. He immediately showed it to Luigi Cherubini, Paris’s leading musician and the head of the Conservatoire, who later recorded the auspicious occasion and his response in his memoirs: “Amazing! You are music itself.” (Interestingly, Cherubini’s response three years later to another boy-genius, Mendelssohn, was noticeably more subdued.) At the Conservatoire the boy studied violin with the leading French violinist of his day, Pierre Baillot, with whom he made extraordinarily rapid progress. But more importantly he joined the composition and fugue class of François-Joseph Fétis, the great Belgian theorist and lexicographer who, in later life, could still hardly contain his astonishment: “His progress was nothing short of prodigious. In less than three months he acquired a perfect knowledge of harmony, and in two years mastered the difficulties of counterpoint and fugue. Arriaga received from nature two faculties which are very seldom found in the same artist: the gift of invention, and the most complete aptitude for all the difficulties of his art …. Nature had created him so as to accomplish everything there is in the realm of music” (Biographie universelle, vol. 1, 1877, pp. 119-20). By 1824 Fétis had arranged for him to receive an assistantship at the Conservatoire, making him, at the age of eighteen, the youngest professor in the institution’s history.

That same year Arriaga had his Premier livre de quatuors, the three string quartets that make up the present volume, published by the respected firm of Philippe Petit in Paris (1824), with a diplomatic dedication to Cherubini “as a token of his respect and affection.” It was the only work published in his lifetime, and it rightly remains the basis of his reputation today. The aged Fétis later saw no reason to retract his original opinion: “It is impossible to imagine anything more original, more elegant, or more purely and correctly written than these quartets, which are still barely known. Every time they were performed by their young creator they excited the admiration of those who heard them” (ibid., p. 120). An Overture, a Symphony, a Mass, a set of piano pieces, and much vocal music quickly followed, as did, perhaps most notably, an eight-voice fugue on Et vitam venturi which Cherubini, a reigning authority on counterpoint, immediately pronounced a masterpiece. But Arriaga’s self-imposed workload evidently took its toll on his health, and two years after the publication of the Quartets he succumbed to a respiratory ailment only a few days before his twentieth birthday. A family friend who witnessed his death wrote to the boy’s father: “The opinion I formed of Juan Crisóstomo was the same as that formed by Fétis, Reicha, Catel, Boïeldieu, Baillot, Berton, and Cherubini [i.e. the leading lights of the French musical world], who believed that if your son had developed for another eight years at a pace proportional to his early achievements he would probably have become one of the chief composers and teachers at the Conservatoire.”

With no one to cultivate his legacy, Arriaga’s works fell into an oblivion from which they were only wakened fifty years later by the impassioned advocacy of his former teacher, Fétis. At this point the ill-starred genius was taken up by the burgeoning Spanish national movement, and Arriaga was stylized into an early unsung hero of musical Spain. The String Quartets were given their first known public performance in Bilbao in 1884 and reissued in print by Dotesio in Bilbao in 1890. By then a Comisión Permanente de las Obras del Maestro Arriaga had been established (1887), followed by a second commission with the same name in 1928 and an Arriaga Society of America in 1955. The composer’s great-grandnephew José de Arriaga e Igartua, using the nom-de-plûme of Juan de Eresaldo, published an edition of the surviving portions of Los esclavos felices accompanied by important new biographical information (1935). But when Dennis Libby wrote his article on Arriaga for The New Grove in 1980, he could rightly state that “Much was published on his life and work, but mostly in a rhapsodic vein, and he still remains little touched by serious critical and scholarly investigation.”

Fortunately this was soon to change. That same year the D-minor String Quartet was analyzed in an American dissertation (M. W. Edson, University of Iowa, 1980); two more dissertations followed in short order (S. K. Hoke, University of Iowa, 1983; J. A. Gómez Rodríquez, University of Oviedo, 1990), as did a detailed and sober-minded biography by Barbara Rosen in the Basque Studies Program of Reno, Nevada (Arriaga, the forgotten genius, 1988). Finally, a complete edition of Arriaga’s surviving music, the Obra completa, has been published by the Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales in Madrid since 2006. But perhaps the most important new publication in our connection is Marie Winkelmüller’s roughly four-hundred-page book on the quartets, Die drei Streichquartette von Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga (Freiburg im Breisgau, 2009), which includes lengthy sections on Arriaga’s biography and historical surroundings and detailed analyses of all three quartets, showing that they are closely based on Beethoven’s op. 18 and thereby represent the cutting edge of Beethoven reception in France at the time.

Nor have Arriaga’s quartets been neglected by performers. They are currently available in a number of excellent recordings, of which the most remarkable is probably that issued by the famous Guarneri Quartet on the Philips label in 1996. With this, Arriaga’s three sparkling string quartets, with their striking melodies, fluent counterpoint, expert workmanship, and bold formal innovations (the guitar-like accompaniment in the Trio of No. 1, the pizzicato variation in the second movement of No. 2, the audacious handling of the pastorale form in No. 3), can be said to have entered the standard repertoire, where they surely belong. It is to be hoped that our publication, newly prepared to correct several errors in previous editions, will help to keep them there.

Bradford Robinson, 2012

For performance material please contact Musikproduktion Höflich (www.musikmph.de), Munich.

Revised version by Lucian Beschiu.

Score Data

| Edition | Repertoire Explorer |

|---|---|

| Genre | Chamber Music |

| Pages | 88 |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |

| Performance materials | available |

| Printing | Reprint |

| Size | 210 x 297 mm |