The Periodical Overtures in 8 Parts – Introduction

The Periodical Overtures in 8 Parts is a remarkable series of sixty-one orchestral symphonies published in London by Robert Bremner between 1763 and 1783. In essence, it was a “symphony-of-the-month” publication over this twenty-year period, capturing the musical tastes of London during the era’s “rage for music.” Bremner was inspired to undertake the series after witnessing the success on the Continent of similar French periodical prints. In England, however, Bremner’s series went unrivaled for a decade, and no other later British publisher came close to matching his success with this periodical format.

From the start, Bremner promised to issue works that had never been printed in Britain and that were composed by “the most celebrated Authors.” He honored both of those commitments, and by 1783, the Periodical Overtures represented some twenty-eight well-regarded composers from across Europe. To accommodate smaller orchestras, the symphonies usually were limited to eight parts, representing first and second violins, viola, bass, a pair of oboes, and a pair of horns, although a few additional instruments began appearing in various issues as British ensembles grew more ambitious. Bremner also catered to a generally conservative British taste by adding figured bass if it were not already present and sometimes reducing the number of movements to three. The works were widely performed, appearing in the records of concert organizations in England, Scotland, and even in the American colonies. Late in the century, several of the most popular issues were arranged for keyboard, reflecting not only the increasing number of pianos in private homes, but also the Periodical Overtures’ staying power.

The objective of these Periodical Overtures Editions in the “Repertoire Explorer” series is to make this unique collection of orchestral works easily accessible and affordable. The music has been edited with a light touch, preserving the authenticity of Bremner’s original prints. Copyist errors have been corrected and notation has been standardized to meet modern conventions, along with the addition of bar numbers, rehearsal letters, and instrumental cues to facilitate performance. Horn parts in F are provided, along with parts in the symphony’s original key. Each score includes a short background and analytical essay along with a summary of the editorial approaches and changes. The Periodical Overtures Editions enrich the repertoire available to chamber orchestras, professional and amateur alike, providing them with valuable historical and musical insights as well as much delightful music-making, a great deal of which is unknown to contemporary audiences and performers.

Historical Background

THE PERIODICAL OVERTURES IN 8 PARTS

Published by Robert Bremner

Edited by Barnaby Priest & Alyson McLamore

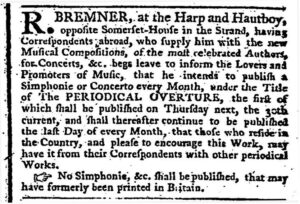

On 25 June 1763, the publisher Robert Bremner (c.1713–1789) inserted an announcement into the London daily newspapers:

Bremner’s advertisement promised several important features: these Periodical Overtures would be “new’ (with the additional clarification that they would not have previously been published in England); they would represent the work of prominent composers, and they would be issued on a monthly basis. To a large extent, Bremner delivered on all those promises: these symphonic works were all unfamiliar to British listeners; the twenty-eight composers represented in the series were almost all well-regarded names; and while the “monthly” pace lagged more and more after the initial twelve months, Bremner sustained the enterprise for twenty years.[1] By the end of 1783, he had issued sixty works—and, after Bremner’s death in 1789, John Preston bought Bremner’s plates, reissued the entire series (with a new title plate), and published a sixty-first overture. Eighteenth-century England had never witnessed a printed music series with such staying power.

Bremner’s advertisement promised several important features: these Periodical Overtures would be “new’ (with the additional clarification that they would not have previously been published in England); they would represent the work of prominent composers, and they would be issued on a monthly basis. To a large extent, Bremner delivered on all those promises: these symphonic works were all unfamiliar to British listeners; the twenty-eight composers represented in the series were almost all well-regarded names; and while the “monthly” pace lagged more and more after the initial twelve months, Bremner sustained the enterprise for twenty years.[1] By the end of 1783, he had issued sixty works—and, after Bremner’s death in 1789, John Preston bought Bremner’s plates, reissued the entire series (with a new title plate), and published a sixty-first overture. Eighteenth-century England had never witnessed a printed music series with such staying power.

Prior to his London success, Bremner had launched his career in Edinburgh—likely the place of his birth—by participating in the city’s vigorous concert life, along with his older brother James.[2] By 1754, he was running a profitable music shop “at the sign of the Golden Harp,” and changed its name to the Harp and Hautboy around 1755.[3] He married Margaret Bruce the following year; their children were Charles, James, and Ellen. Upon Bremner’s death, the bulk of his estate was left to Ellen, but the boys received £760 11s. 1d apiece.[4] Bremner was probably a violinist, judging from a teasing message he sent to the Revd. Charles Wesley (1707–1788) regarding his son Samuel’s (1766–1837) playing technique: “Tell that Ruffian Sam, that I will pay him a visit soon with a Claymore by my side and that I am determined to cut off any part of his bow hand elbow that gets behind his back when he fiddles. I cannot bear to see him imitate a Taylor.”[5]

Bremner’s publications catered to a variety of musical needs: he printed guidance in thorough-bass, a primer on music rudiments, and repertory for popular instruments such as fiddle and guitar.[6] Moreover, in 1761, he published six overtures by Thomas Alexander Erskine, 6th Earl of Kelly (1732–1781), who had trained in Mannheim with the celebrated composer Johann Stamitz (1717–1757). These were among the first British compositions to display the dazzling orchestral effects popularized by the Mannheim orchestra, and this publication of Lord Kelly’s opus 1 reflected Bremner’s acumen as a businessman.[7]

A Continental Avalanche

Bremner clearly had an eye for opportunities, which likely propelled him to expand his enterprises by opening a second “Harp and Hautboy” shop in London in 1762—and which alerted him to a publishing model that was exploding in France.[8] Two years earlier, the Parisian publisher Louis Balthazard de La Chevardière (1730–1812) had already issued sixteen works in his Recueil périodique en Simphonies. By 1765, he had published sixty-five symphonies, although his pace then slowed dramatically, and it was not until 1772 that he reached sixty-eight items in his series.[9] For the first thirty-nine symphonies, the catalogue almost always noted that each work came “con Oboe,” except for No. 5 by Cannabich, which contained “Flauti” parts, and No. 3 by “Holtzbaur” (Holzbauer), in which “Corni” were announced.[10] Despite this reference to horns in the third symphony, however, La Chevardière’s works routinely included horn parts. Intriguingly, while writing in his journal during his 1770 trip to France, Charles Burney mentioned in passing that La Chevardière was “in correspondence with Bremner,” but it is unclear how long the two music sellers had been communicating, nor do we know the specific nature of their interactions.[11]

La Chevardière quickly had competition in Paris. Again in 1760, a catalogue for Jean Baptiste Venier (fl. 1755–1784) listed his offerings in a series titled Sinfonie a Più Stromenti Compte da Vari Autori. Venier issued his symphonies in sets of six, assigning an opus number to each set; the 1760 catalog showed that he had reached “Opera 11a,” and three more sets would appear over the next five years. In contrast to La Chevardière, Vernier customarily listed the presence of parts for corni (only) in his catalogue, although the actual sets contained oboes as well. It was not until Opera 12 that he stipulated both “Corni e Oboé adlibitum.”[12] However, Vernier had intensified his rivalry by 1763, when he also had published the first dozen of his Sinfonies périodiques.[13] His publication pace was slower than that of his colleague; it was not until the early 1780s that a catalogue advertised a forty-sixth symphony (although the listing lacked symphonies 34 through 36, a gap that had persisted since the late 1760s and would still appear in a 1788 catalogue).[14]

These two Parisian publishing houses were not alone. In 1762—the same year that Bremner was setting up shop in London—a third French printer, Antoine Huberty (c.1722–1791), advertised nine Simphonies Periodiques, and he reached a total of twenty-four by 1770.[15] Nearby, Jean-Georges Sieber (1738–1822) had published at least two (unnumbered) items in his Sinfonie Periodique series by 1772, and would eventually reach eighty-eight works in all. By 1778, Sieber had adopted the practice of assigning numbers sequentially to the works of individual composers (but continued to issue them under the “périodique” heading). His son Georges-Julien Sieber (1775–1847) was still advertising their firm’s periodical symphonies at the start of the nineteenth century.[16]

Not all French publishers enjoyed similar success. In the mid-1770s, the skilled engraving team of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme (c.1732–after 1795) and François Moria (c. 1720–1776) issued their first Sinfonia Periodique a Piu Stromenti, but further works in their series are now lost, if they had ever existed.[17] Pierre Leduc “le jeune” (1755–1826) launched his own Simphonies periodiques series in 1776, but had published a total of only seventeen works by 1781. Five years later, he acquired La Chevardière’s stock—but dropped the periodical symphonies altogether from his catalogue at that point.[18]

In the 1780s, when Bremner’s series was winding down across the English Channel, at least one more French publisher entered the ranks with a new series titled Sinfonie Periodique—Divers Instrumens. Jean-Jérôme Imbault (1753–1832) went on to produce almost seventy periodical items by 1793. He had started business in 1784 in partnership with Sieber, but began publishing on his own after about a year. From the start of his own periodical series, he adopted the practice of Sieber that assigned numbers to each composer; Imbault issued twenty-four symphonies by Pleyel alone.[19]

Besides the impetus they gave to Bremner in England, the French printers inspired publishers in other nations as well. At least two series appeared in Amsterdam in the 1770s. The composer Jean (Johann) Gabriel Meder (1729–1800) is known to have printed two of his works as Simphonies Periodiques at the start of the decade, and about five years later, Siegfried Markordt (c.1720–1781) published Six Symphonie Périodique à 8 Instruments (which were in actuality Johann Christian Bach’s Op. 8 symphonies).[20] In comparison to France, however, the Dutch output was quite modest.

The Ancients versus the Moderns

In London, Bremner encountered no direct competition for at least the first decade of his enterprise, which may have been due in part to the whirl of conflicting tastes in Britain. The combatants were commonly known as “Ancients” and “Moderns,” comprised of those who clung tightly to music and styles that were familiar and those who were eager to hear new works. Lord Kelly represented the “new music” enthusiasts when he traveled to the continent in order to learn the latest trends of the Mannheim School. Countless London concert advertisements announced the inclusion of works that were “new,” “never before heard,” or even “in manuscript” to emphasize their exclusivity and freshness.[21] By 1793, one musical commentator, the Revd. Richard Eastcott of Exeter (bap.1744–1828), argued that “the public taste for music . . . was perhaps never in a higher state in any period than at present. The beautiful symphonies, concertos, quartetts, &c. &c. lately produced are daily mounting on eagle wings to the sublime attitude of superiour excellence.”[22]

In sharp contrast, in 1764—a year after The Periodical Overtures made their debut—the composer Charles Avison (1709–1770) complained about that same new repertoire. He published a lament in the preface to his Six Sonatas for the Harpsichord, expressing his dismay over “the innumerable foreign Overtures, now pouring in on us every Season, which are all involved in the same Confusion of Stile, instead of displaying the fine Varieties of Air and Design. Should this Torrent of confused Sounds, which is still encreasing, overpower the public Ear: we must in Time prefer a false and distracted Art, to the happy Efforts of unforced Nature.”[23]

Avison was not alone in his reactionary attitude. In 1766, John Gregory (1724–1773) agreed that “the general admiration pretended to be given to foreign Music in Britain, is in general despicable affectation.”[24] He predicted that the new German style’s “wild luxuriancy” was possessed of too little “elegance and pathetic expression . . . to remain long the public Taste.”[25] In the next decade, one of the founding principles of the Concert of Ancient Music (1776) was the prohibition of works that were less than twenty years old, while in 1784, London witnessed the first of the grandiose Handel Commemoration Concerts, celebrating the beloved composer who had died twenty-five years earlier.[26] But, despite the prominence of public enterprises that looked to the past for their repertory, the thirst for new music seemed equally unquenchable. Bremner’s Periodical Overtures clearly fed that appetite.

The Parameters of the Periodical Overtures

Bremner adopted various publishing features from his French models but adapted them to suit his British customers. His use of the term “overture” reflected the widespread English treatment of the word as a synonym for “symphony,” a practice that would persist to the end of the century. Still, at least eleven of The Periodical Overtures in 8 Parts were indeed taken from the overtures of operas, a fact that was reflected in some (but not all) of the specific issues’ parts or advertisements. From the start, Bremner’s title clarified the customary scoring for two violins, viola, “basso,” two oboes, and two French horns. Many of the surviving sets held in archives contain two copies of the basso part, clarifying its use both by violoncellos and by double-basses; a number of the basso parts also include cues for passages when cellos (or bassoons) are to be featured. As the series continued, various overtures contained movements in which flutes or clarinets were substituted (or added), and parts for other instruments appeared with greater frequency (although the “8 Parts” designation on the title page never wavered).

Some features of Bremner’s series may have been calculated to appeal to those with “ancient” tastes. The basso parts routinely contain figured bass, with occasional moments marked for “tasto solo,” clarifying that basso continuo performance could remain ongoing. In some cases, Bremner seems to have added the thoroughbass figures himself, since they are not present in contemporary editions published on the continent. Again, perhaps in accordance with British preferences, Bremner often omitted minuet-and-trio movements that were available in other European editions (and presumably had existed in his sources).

Bremner created something of a “blend” of practices as he labeled the items within his series. Like La Chevardière and Venier, he numbered his Periodical Overtures sequentially, in the order of their appearance. However, he also took a leaf from Vernier’s Sinfonie a Più Stromenti: as he advertised the sixth Periodical Overture on 1 December 1763, he announced, “N.B. As this Number compleats the first set, those who have got the former Numbers will please to call for a general title to all the Parts.”[27] He then referred to the seventh through twelfth symphonies as “Opera 2,” again creating a title page that listed all six of them. As David Wyn Jones notes, this packaging probably appealed to customers who were “conscientious collector[s].”[28] Bremner continued the practice with each subsequent group of six overtures, leading to ten volumes in all; Preston does not seem to have assigned a new volume number to his brief extension of the series.

The Periodical Composers

By the end of The Periodical Overtures, there had been twenty-eight contributors to Bremner’s enterprise, which was a much wider diversity than in any of the French publishers’ series. La Chevardière, for instance, included about half as many names.[29] The total did not change when Preston took possession of the plates; Preston’s No. 61 was a second symphony by Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–1799), who had previously been represented by Periodical Overture No. 38. Nine of the composers—almost fifteen percent of the total—had been living in London while the issues in the series appeared, so it is likely that there was direct contact between the creators and Bremner in those cases.[30]

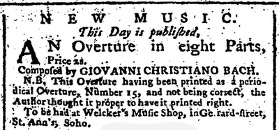

Proximity between composer and publisher did not always ensure an optimal result. The composer whose composition had launched The Periodical Overtures was Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782). On 4 August 1766, scarcely a month after Bach had been included in the series for a second time, the following indignant advertisement appeared at the top of the first page of The Public Advertiser:

Despite this dissatisfaction with inaccuracies in Periodical Overture No. 15, Bach presumably agreed to have another of his works published by Bremner, and Periodical Overture No. 44 was announced in May 1775.[31]

Despite this dissatisfaction with inaccuracies in Periodical Overture No. 15, Bach presumably agreed to have another of his works published by Bremner, and Periodical Overture No. 44 was announced in May 1775.[31]

The remaining eighty-five percent of composers in the series were non-residents of England, thereby contributing to the flood of “innumerable Foreign overtures” that kept “pouring in,” much to the ire of Charles Avison. Beyond Bremner’s claim of “correspondents abroad” in his preliminary announcement for The Periodical Overtures, little is known about the methods by which he obtained his repertory. Jones notes that there were three “usual and accepted methods of acquiring texts”: “[1] business contacts between publishers . . . [2] direct negotiation with the composer . . . [and 3] simple plagiarism of printed and manuscript copies returned to England by European travellers.”[32]

It seems, from Burney’s comment in 1770, that Bremner may have employed the first approach by corresponding with La Chevardière, although the extent of their dealings is unclear. However, Jones believes that “it was largely through [Bremner’s] pioneering efforts [in building ties with the main commercial publishing centers] that London in the 1780s was able to challenge Paris as the publishing capital of musical Europe.”[33] It is also likely that Bremner adopted the second approach as well, since he is known to have traveled to France and Holland at least once prior to 15 February 1773, returning with a “collection of Overtures.”[34] None of Bremner’s business records survive, so it is impossible to judge if his ethics steered him away from the third potential source of repertory.

Bremner consistently sought to include new musical fashions, and thus The Periodical Overtures shifted their stylistic focus over their twenty-year span. Mannheim or Mannheim-influenced composers predominated in the first half of the series. Gradually, though, more works from Austria and from France began to appear.[35] Johann Stamitz had been represented by six symphonies among the first thirty published, but had only two more appear in the second half of the series. In contrast, the Austrian composer Johann Baptist Vanhal (1739–1831) was included only in the final third of the overtures, yet also was featured in eight works. This stylistic shift often required a greater number of instruments as well as the inclusion of a fourth movement; it certainly reflects the increasing ambition of orchestral ensembles.

Challenges to the Monopoly

Given the significant number of rival “périodique” publications in Paris, it is surprising that Bremner met with so few local challengers to his initially exclusive publishing project. The surviving examples of prints from his competitors are difficult to date, but they seem to have begun appearing more than a decade after Bremner launched his Periodical Overtures. Several of these copied Bremner’s title verbatim, such as John Johnston’s (fl. 1767–1778) c. 1775 issue of a work by Pierre van Maldere as A Periodical Overture in Eight Parts.[36] Similarly, around 1780, John Bland (c.1750–c.1840) issued two symphonies by “Kotzwara” (František Kocžwara), again designated as A Periodical Overture in Eight Parts.[37] Approximately five years later, John Kerpen (fl. c.1782–1785) published a likely spurious “Haydn” symphony, yet again with the same The Periodical Overture in Eight Parts title.[38] As late as 1810, William Hodsoll (fl. c.1794–c.1830)—who took over John Bland’s firm after two intermediary owners—reissued the “Kotzwara” works.[39]

There were some exceptions to the “cloned” titles, some of which omitted the word “periodical” altogether. J. Betz (fl. 1775–1780) began a series of pieces, each designated as “A Single Sinfonie. By different Authors.” Above this title was the declaration “To be Continued Monthly.” He issued at least three symphonies by Vanhal, identifying them as “A,” “B,” and “C.”[40] In 1777, Ab. Portal (fl. c.1775–1780) published The Overture of the Syrens . . . for Two Violins, Tenor, & Base [sic], Two Hautboys, Two French Horns ad libitum.” He then added a note: “N.B. The OVERTURES will be so contrived as to form Quartetts for private Concerts when a full band is not to be had and it is intended to publish five more successively in the same manner to bind up together.”[41] This comment probably reflects a desire to please the music “collector,” but it also clarifies a rationale for the expendability of the winds in so many of these “eight-part” works.

Interestingly, late in the century, Preston himself launched a new series, retaining the “periodical” designation but using the more modern “sinfonie” genre term. He apparently was not interested in seeking out new, unknown works, in the manner of Bremner. Instead, his full title read, “Periodical Sinfonie for 2 Violins, Tenor, & Bass, Horns & Hautboys, ad Libitum, as Perform’d at the Principal Concerts.” He issued at least nine works in the series; all of the six surviving symphonies were by Ignace Pleyel (1757–1831).[42]

Even though Bremner faced no major competitors during the two decades that he published The Periodical Overtures, his enterprise clearly sparked a number of “spin-off” ventures. William Forster the Elder (1739–1808) published at least six Periodical Quartettos in the 1780s.[43] He may have taken inspiration from Bremner’s own Periodical Trios; Bremner published at least two, both by Pergolesi, in 1771–2.[44] In turn, Robert Wornum (1742–1815) had reached his fourth item labeled The Periodical Trio for Two Violins and a Violoncello by c. 1775.[45] Moreover, several publishers issued periodical vocal music—primarily songs—which had been true in France as well.

The Periodical Overtures’ Reach and Staying Power

Although many concert programs began to be advertised in newspapers in the second half of the eighteenth century, their information about their instrumental repertory is frustratingly cryptic. One virtue to Bremner’s near-monopoly in Britain is that any reference to a “Periodical” overture is almost certainly an item from his series. It is therefore evident that copies of The Periodical Overtures were well traveled. The Edinburgh Musical Society orchestral catalogue lists Periodical Overtures 1–46 and 50–54, but Jenny Burchell notes that Nos. 47, 49, 56, and 60 all had performances in the Society’s concerts, so they almost certainly owned the entire set.[46] The Periodical Overtures traveled even further than Scotland, with two of them appearing in a concert program in Boston on 17 May 1771. Josiah Flagg (1737–1794) led the band of the 64th Regiment in a performance that included “Periodical Symphonies” by Stamitz and Ricci.[47]

Another measure of success for The Periodical Overtures was their subsequent conversion into keyboard arrangements. These adaptations were issued by numerous publishers. Samuel Babb (fl. c.1770–1786) sold The Favorite Periodical Overture in the early 1780s; this was an arrangement of Anton Filtz’s Periodical Overture No. 4.[48] About the same time, William Smethergell (bap.1751–1836) adapted Niccolò Jomelli’s Periodical Overture No. 14 to create The Favorite Periodical Overture and Chaconne, which was published by the music-sellers Longman and Broderip; they were still selling copies as late as 1805, when the firm had become Broderip and Wilkinson.[49] Periodical Overture No. 11, by Johann Stamitz, was adapted by a “Mr. Hartley” in c. 1783 on behalf of the firm of Birchall and Beardmore.[50] When The Piano-Forte Magazine began to be published, it included in its second volume (1798) an arrangement of Ditters’s Periodical Overture No. 38.[51]

As late as 1826, the Periodical Overtures remained in the memories of concert-goers. A correspondent writing to The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review recalled an old saying that the typical three-movement structure was targeted at different segments of the audience: “The first movement was always calculated for the meridian of the pit, the second for the more refined audience of the boxes, and the third for the gallery auditors.”[52] The writer (using the nom de plume “Senex”) pointed to the popular Periodical Overture No. 20 by Niccolò Piccinni (1728–1800) as a typical specimen. Senex felt the overtures in Bremner’s series had ushered in increased attention to wind instruments, which he believed had been “but little understood” by the preceding generation of symphonists. He also applauded the innovative crescendo and diminuendo passages that could be found in Stamitz’s Periodical Overture No. 11 as contributors to “the early progress . . . of the modern symphony.”[53]

Even near the end of his life, Bremner remained a determined businessman. In the summer of 1788, five years after the appearance of the sixtieth Periodical Overture, Bremner issued an announcement that several of his “excellent Publications have been suffered to get out of print, owing to a long and severe illness: but he having now recovered his health, so far as to be able again to attend his business, no time shall be lost in publishing the remainder.”[54] The announcement was repeated a month later, and by the end of November, Bremner advertised “New Impressions” of many works, including Periodical Overtures Nos. 38, 52, 56, and 60.[55] Half a year later, however, Bremner died in his home at Kensington Gore, London, on 12 May 1789. He left behind properties at Battersea Rise and Brighton as well as his two music shops.[56] Clearly, he had risen to a position of considerable affluence, thanks to the success of his various ventures as a music retailer. The quality of his establishment’s workmanship is still apparent in the clear engraving and heavy-weight paper he employed. These qualities have helped hundreds of copies of The Periodical Overtures to survive to this day in archives ranging from Scandinavia to the United States. The longevity of Bremner’s enterprise remains a testament to his skill in selecting quality repertory that appealed to the diverse and variable tastes of a bustling music-loving society.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Series announcement: The St. James’s Chronicle; or, The British Evening-Post, Saturday, 25 June, to Tuesday, 28 June, 1763, p. 2 (courtesy of the British Library Archives)

Welcker announcement: The Public Advertiser, 4 August 1766, p. 1 (courtesy of the British Library Archives)

FOOTNOTES

[2] Frank Kidson, British Music Publishers, Printers, and Engravers: London, Provincial, Scottish, and Irish. From Queen Elizabeth’s Reign to George the Fourth’s, with Select Bibliographical Lists of Musical Works Printed and Published Within That Period (London: W. E. Hill & Sons, [1900], 15.

[3] Charles Humphries and William C. Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles from the Beginning Until the Middle of the 19th Century, 2nd ed. (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1970), 84.

[4] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. “Bremner [Brymer], Robert,” by Mary Anne Alburger, accessed 20 February 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/3316.

[5] Robert Bremner to Charles Wesley Sr, letter of 18 November 1780; the Methodist Archives and Research Centre, MARC DDWES 7/110.

[6] David Johnson, “Robert Bremner,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 4: 314.

[7] David Johnson “Kelly [Kellie], 6th Earl of,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 13: 464.

[8] Bremner left John Brysson to manage the Edinburgh shop; Grove Music Online, s.v. “Bremner, Robert.”

[9] Cari Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues of the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century: Facsimiles (Malmö, Sweden: AB Malmö Ljustrycksanstalt, 1955), Facsimiles 45, 50, and 56.

[10] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimile 45.

[11] Charles Burney, Music, Men and Manners in France and Italy 1770: Being the Journal Written by Charles Burney, Mus.D., during a Tour Through Those Countries Undertaken to Collect Material For a General History of Music, ed. H. Edmund Poole (London: Eulenburg Books, 1974), 21-22.

[12] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 118 and 119.

[13] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimile 119.

[14] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 101, 122, and 124.

[15] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 25 and 31.

[16] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 103 and 117.

[17] Mark Ledbury, “Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, François Moria and Music Engraving in the Choix de Chansons,” Choiz de Chansons, 2022, https://choixdechansons.cdhr.anu.edu.au/marie-charlotte-vendome-francois-moria-and-music-engraving-in-the-choix-de-chansons/.

[18] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 64, 81, and 86.

[19] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimile 39; Rita Benton, “Imbault, Jean-Jérôme,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 12: 87.

[20] Christoph Wolff and Stephen Roe, “Bach, Johann (John) Christian,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 2: 423.

[21] Laura Alyson McLamore, “Symphonic Conventions in London’s Concert Rooms, circa 1755–1790,” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1991), 11.

[22] The Revd. Richard Eastcott of Exeter, Sketches of the Origin, Progress and Effects of Music with an Account of the Antient Bards and Minstrels (Bath: S. Hazard, 1793), 158.

[23] Charles Avison, “Advertisement,” Six Sonatas for Harpsichord. With Accompanyments For two Violins and a Violoncello (London: R. Johnson, 1761), 1.

[24] John Gregory, A Comparative View of the State and Faculties of Man with those of the Animal World, new ed. (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1766), 157

[25] Gregory, A Comparative View, 177; also quoted in Simon McVeigh, Concert Life in London from Mozart to Haydn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 121.

[26] McLamore, “Symphonic Conventions,” 145–6; Rosemary Halton, “From Hailstones to Hallelujah: The First Handel Commemoration,” in A World of Popular Entertainments: An Edited Volume of Critical Essays, ed. Gillian Arrighi and Victor Emeljanow (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 192.

[27] The Public Advertiser, 1 December 1763, 2.

[28] Jones, “Robert Bremner and The Periodical Overture,” 65.

[29] Johansson, French Music Publishers’ Catalogues, Facsimiles 56 and 62.

[30] The nine were Abel, Arne, Bach, the Earl of Kelly, Guglielmi, Herschel, Pugnani, Ricci, and Sacchini; see Jones, “Robert Bremner and The Periodical Overture,” 66.

[31] The Public Advertiser, 13 May 1775, 2.

[32] Jones, “Robert Bremner and The Periodical Overture,” 66.

[33] David Wyn Jones, “Haydn’s Music in London in the Period 1760–1790, Haydn Yearbook 14 (1983): 153.

[34] Jenny Burchell, Polite or Commercial Concerts?: Concert Management and Orchestral Repertoire in Edinburgh, Bath, Oxford, Manchester, and Newcastle, 1730–1799, Outstanding Dissertations in Music from British Universities, ed. by John Caldwell (New York: Garland Publishing, 1996), 73.

[35] Jones, “Robert Bremner and The Periodical Overture,” 66-7.

[36] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 195.

[37] Frank Kidson, William C. Smith, and Peter Ward Jones, “Bland, John,” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 3: 684.

[38] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 200.

[39] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 182.

[40] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 70.

[41] John Abraham Fisher, The Overture of the Syrens . . . for Two Violins, Tenor, & Base, Two Hautboys, Two French Horns ad libitum (London: Ab Portal, 1777), 1.

[42] Rita Benton, “Pleyel, Ignace Joseph [Ignaz Josef],” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 19: 921.

[43] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 149.

[44] The Public Advertiser, 26 November 1771, 2.

[45] Peter Ward Jones, “Wornum [Wornham],” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 2001), Vol. 27: 571.

[46] Burchell, Polite or Commercial Concerts?, 72.

[47] Harold Gleason and Warren Becker, Early American Music: Music in America from 1620 to 1920, 2nd ed. (Bloomington, IN: Frangipani Press, 1981), 25; Charles Hamm, Music in the New World (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), 84–5.

[48] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 58.

[49] Niccolò Jomelli, the Favorite Periodical Overture and Chaconne (London: Longman & Broderip, 1780?), 1.

[50] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 75.

[51] Imogen Fellinger, ed., Periodica Musicalia (1789–1830) im Auftrag des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Studien zur Musikgeschichte des 19. Jarhhunderts, Vol. 55 (Regensburg: Gustav Bosse, 1986), 88.

[52] Senex, “To the Editor,” The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review 8, no. 31 (July 1826): 304.

[53] Senex, “To the Editor,” 304–5.

[54] The Morning Post, 16 August 1788, 1.

[55] St. James Chronicle, or the British Evening Post, 9–11 September 1788, 1; The World, 22 November 1788, 2.

[56] Humphries and Smith, Music Publishing in the British Isles, 83-4.

CATALOGUE

The Periodical Overtures – Published by Robert Bremner

Periodical Overture 01

Composer Bach, John Christian (1735-1782)

RISM B.257

Date of issue Jun 30 1763

Opera Gli uccellatori = The Bird-Catchers (1760 production)

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 8:12

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 02

Composer Ricci, Francesco Pasquale (1732–1817)

RISM R.1273

Date of issue Aug 1 1763

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 7:20

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 03

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4595

Date of issue Aug 31 1763

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 11:02

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 04

Composer Fils [Filtz], Anton (1733-1760)

RISM F.774

Date of issue Oct 5 1763

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 14:20

2 violins, “alto viola,” bass, 2 flutes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 05

Composer Crispi, Pietro Maria (1737–1797)

RISM C 4416

Date of issue Oct 30 1763

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 6:43

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 06

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4597

Date of issue Dec 1 1763

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 19:17

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 07

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4598

Date of issue Jan 2 1764

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 16:55

2 violins, “alto viola,” bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 08

Composer Fils [Filtz], Anton (1733-1760)

RISM F.775

Date of issue Feb 4 1764

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 13:11

2 violins, “alto” [viola], bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 09

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4599

Date of issue Feb 29 1764

Key G

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 12:26

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 10

Composer Cannabich, Christian (1731-1798)

RISM C.829 / C.830

Date of issue Apr 5 1764

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 16:23

2 violins, 2 oboes, viola, bass, 2 flutes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 11

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4600

Date of issue May 1764

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 16:30

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 12

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4601

Date of issue Jun 2 1764

Key F

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 16:28

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 13

Composer Erskine, Thomas Alexander [Earl of Kelly] (1732-1781)

RISM E.775

Date of issue May 15 1766

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 10:51

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 flutes [divisi], 2 oboes [divisi], 2 horns

Periodical Overture 14

Composer Jommelli, Niccolò (1714-1774)

RISM J.595 / J.597

Date of issue May 31 1766

Opera Demetrio (transposed); Chaconne “As Introduced at the Castle Spectre”

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 2

Duration 7:07

2 violins, viola, bass (bsn cues), 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 15

Composer Bach, John Christian (1735-1782)

RISM B.253

Date of issue Jul 1 1766

Opera La Giulia

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 10:14]

2 violins, 2 violas, bass, 2 oboes [flutes in mvt. 2], 2 horns

Periodical Overture 16

Composer Abel, Carl Friedrich (1723-1787)

RISM A.80

Date of issue Aug 4 1766

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 4:36

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 17

Composer Erskine, Thomas Alexander [Earl of Kelly] (1732-1781)

RISM E.776

Date of issue Oct/Dec 1766

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 8:20

2 violins, viola, bass (bsn cues), 2 flutes [divisi], 2 Bb clarinets [divisi], 2 horns

Periodical Overture 18

Composer Richter, Franz (1709-1789)

RISM R.1340

Date of issue bef Feb 7 1767

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 13:14

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 19

Composer Pugnani, Gaetano (1731-1798)

RISM P.5573

Date of issue Aug 20 1767

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 9:34

2 violins, 2 violas [divisi], bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 20

Composer Piccinni [Piccini], Niccolò (1728-1800)

RISM P.2071

Date of issue Sept 7 1767

Opera La Cecchina, ossia La Buona Figliuola

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 5:44

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 21

Composer Piccinni [Piccini], Niccolò (1728-1800)

RISM P.2215

Date of issue Sept 24 1767

Key F

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 5:50

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 22

Composer Piccinni [Piccini], Niccolò (1728-1800)

RISM P.2215

Date of issue Dec 22 1767

Opera Le contadine bizzarre

Key G

No. of Mvts. 2 (3)

Duration 6:45

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 23

Composer Piccinni [Piccini], Niccolò (1728-1800)

RISM P.2215

Date of issue bef Mar 9 1768

Opera Antigono; also L’Astrologo

Key F

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 6:47

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 24

Composer Ricci, Francesco Pasquale (1732–1817)

Date of issue 1768?

RISM R.127

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 13:20

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 25

Composer Erskine, Thomas Alexander [Earl of Kelly] (1732-1781)

RISM E.777

Date of issue Jun 10 1769

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 15:10

2 violins,viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 26

Composer Herschel, Jacob (1734-1792)

RISM H.5194

Date of issue Dec 2 1769

Key C

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 7:26

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 27

Composer Arne, Thomas Augustine (1710-1778)

RISM A.1834

Date of issue Apr 4 1770

Opera Guardian Outwitted, The

Key G

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 5:32

2 violins, viola, cello, 2 flutes [divisi], 2 oboes, 2 horns, 2 bassoons [divisi]

Periodical Overture 28

Composer Erskine, Thomas Alexander [Earl of Kelly] (1732-1781)

RISM E.778

Date of issue May/Dec 1770

Opera Maid of the Mill

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 9:33

2 violins, viola, bass (+ bassoon), 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 29

Composer Holzbauer [Holtzbauer], Ignaz (1711-1783)

RISM H.6376

Date of issue Dec 15 1770

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 14:52

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns, 2 bassoons [divisi]

Periodical Overture 30

Composer Fils [Filtz], Anton (1733-1760)

RISM F.776

Date of issue Feb 27 1771

Key F

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 20:36

2 violins, “alto viola,” bass, 2 oboes [or Flauto], 2 horns

Periodical Overture 31

Composer Guglielmi, Pietro Alessandro (1728-1804)

RISM G.4981

Date of issue bef Sept 26 1771

Opera Pazzie d’Orlando, La

Key D

No. of Mvts. 2

Duration 8:45

2 violins, “alto viola,” bass, 2 oboes (or flutes), 2 bassoons (divisi), 2 horns

Periodical Overture 32

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3165

Date of issue Oct/Dec 1771

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 14:58

2 violins,viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns,

Periodical Overture 33

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3166

Date of issue Jan 4 1772

Key G

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 17:42

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 34

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3167

Date of issue Feb/May 1772

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 14:19

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 35

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3168

Date of issue Feb/May 1772

Key C

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 19:43

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 36

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3169

Date of issue Jun 22 1772

Key F

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 20:55

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 37

Composer Fränzl [Franzl], Ignaz (1736-1811)

RISM F.1567 / F.1566

Date of issue Sept 9 1773

Key F

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 15:59

2 violins, 2 horns, viola, bass [first page i.d.’ed as Fagotti], 2 horns, 2 clarinets

Periodical Overture 38

Composer Dittersdorf [Ditters], Carl Ditters von (1739-1799)

RISM D.3280

Date of issue Dec 7 1773

Key C

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 9:36

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 39

Composer Schwindl, Friedrich (1737-1786)

RISM S.2562

Date of issue Apr 23 1774

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 12:49

2 violins, viola [“alto”], bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 40

Composer Haydn, Michael (1737-1806) & Joseph (1732-1809)

RISM HH.3282b

Date of issue Bef Nov 9 1774

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 8:58

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 41

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4602

Date of issue Bef Nov 9 1774

Key D

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 19:58

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 42

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.310

Date of issue Nov 5 1774

Key C

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 21:44

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 clarinetti in C, flute, 2 oboes [divisi], 2 horns, timpani

Periodical Overture 43

Composer Stamitz, Johann Wenzel Anton (1717-1757)

RISM S.4603

Date of issue Bef May 13 1775

Key F

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 15:31

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 44

Composer Bach, John Christian (1735-1782)

RISM B.251

Date of issue May 13 1775

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 9:42

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 45

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.318

Date of issue June/Oct 1775

Key F

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 22:54

2 violins, viola, 2 basses [divisi], 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 46

Composer Gossec, François-Joseph (1734-1829)

RISM G.3170

Date of issue Nov 28 1775

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 16:50

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 47

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.331

Date of issue Dec 1775

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 16:55

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 48

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.320

Date of issue Jan 24 1776

Key G

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 18:26

2 violins, viola, cello, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 49

Composer Sacchini, Antonio (1730-1786)

RISM S.296

Date of issue Oct 16 1776

Opera Perseo

Key c

No. of Mvts. 2

Duration 8:11

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 50

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.324

Date of issue Apr 26 1777

Key A

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 17:56

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes [flute in mvt. 2], 2 horns

Periodical Overture 51

Composer Schmitt, Joseph (1734-1791)

RISM S.1808

Date of issue Jun 77/Feb 1778

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 19:10

2 violins, 2 violas [divisi], bass, 2 oboes , 2 horns

Periodical Overture 52

Composer Cannabich, Christian (1731-1798)

RISM C.831

Date of issue Mar 11 1778

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 12:24

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 53

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.313

Date of issue Dec 15 1778

Key D

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 14:47

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 clarinets [divisi], 2 oboes [divisi], 2 horns [timpani]

Periodical Overture 54

Composer Boccherini, Luigi (1743-1805)

RISM B.3224

Date of issue May 24 1779

Key B♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 12:04

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 flutes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 55

Composer Boccherini, Luigi (1743-1805)

RISM B.3224

Date of issue Jul 79 / Oct 1780

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 18:16

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 flutes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 56

Composer Haydn, Michael (1737-1806)

RISM H.4829

Date of issue Nov 30 1780

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 4

Duration 17:20

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 57

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.322

Date of issue 1781/1782

Key g

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 18:02

2 violins[Violin 1 divisi], 2 violas [divisi], bass, 2 oboes, 4 horns [2 divisi]

Periodical Overture 58

Composer Wanhal [Vanhal], Johann Baptist (1739-1813)

RISM V.316

Date of issue After March 1782

Key d

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 12:12

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, 4 horns [divisi]

Periodical Overture 59

Composer Schobert, Johann (c.1735-1767)

RISM S.2026

Date of issue 1781/1782

Key E♭

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 19:10

2 violins, 2 violas, bass, 2 oboes, 2 horns

Periodical Overture 60

Composer Gluck, Christoph Willibald (1714-1787)

RISM G.2770

Date of issue Feb 13 1783

Opera Iphigenie en Aulide (“to Midia and Jason here”)

Key C

No. of Mvts. 1

Duration 9:50

2 violins, viola, bass, 2 flutes [divisi], 2 oboes [divisi], 2 horns [divisi], bassoon, 2 trumpets

Periodical Overture 61

Composer Dittersdorf [Ditters], Carl Ditters von (1739-1799)

RISM D.3281

Date of issue 1790?

Key D

No. of Mvts. 3

Duration 11:05

2 violins, viola, cello, 2 flutes [with oboe cues], 2 horns

Downloads & Links

LINK TO RECORDINGS > www.barnabypriest.com

DOWNLOAD HISTORCAL BACKGROUND > HERE

DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE > HERE