|

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth

(geb. London, 12. Juli 1885 — gest. bei Thiepval, Nord-Frankreich)

Volume 1

Orchesterwerke

Two English Idylls

(1910-1911)

Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad

(1911)

The Banks of Green Willow

(1913)

Elf Lieder nach A Shropshire Lad

(1910–1911)

(Bearbeitung für Stimme und kleines Orchester von Phillip Brookes)

Das Leben von George Butterworth

George Butterworth war einer der bedeutendsten britischen Komponisten in den Jahren vor dem ersten Weltkrieg, der ihn auf tragische Weise das Leben kosten sollte. Er komponierte exquisite Orchesterwerke, außerdem bewegende und eindringliche Lieder, insbesondere nach Worten von A. E. Housman. Er war außerdem ein bedeutender Ex-ponent der Wieder-Entdeckung des britischen Folk-Songs und sogar einer der begabtesten Volkstänzer seiner Zeit, verantwortlich für die Bewahrung etlicher historischer Tänze. Der Sohn eines Anwalts wurde zwar in London geboren, wuchs jedoch in York auf, wo sein Vater damals als Manager der North-East Railway arbeitete. Später besuchte er Eton und das Trinity College, Oxford, um klassische Literatur zu studieren. Schon in Eton zeigte Butterworth vielversprechende musikalische Begabung und schrieb etliche Werke, die vom dortigen Schulorchester aufgeführt wurden, insbesondere eine Barcarolle für Orchester, die allerdings verschollen ist. In Oxford befreundete er sich mit dem Komponisten Ralph Vaughan Williams, mit dem Dirigenten und späteren Gründer des BBC Symphony Orchestra Adrian Boult und mit Hugh Allen, dem späteren Direktor des Royal College of Music. 1906, mit 21 Jahren, trat Butterworth der neu gegründeten Folk Song Society bei und widmete sich begeistert der Sammlung alter Volkslieder in ganz Britannien. Er zeichnet für die Bewahrung von immerhin 300 Liedern verantwortlich – weniger als Vaughan Williams, Grainger oder Holst, doch gleichwohl ähnlich bedeutend. Für kurze Zeit arbeitete er als Musik-Kritiker für die Times und als Musiklehrer am Radley College, Oxfordshire – wo man sich an ihn allerdings am ehesten für seine Fähigkeiten im Cricket-Spiel erinnerte. Zu dieser Zeit begann er mit seinen Vertonungen nach Housmans Shropshire Lad. Im Jahr 1910 schrieb er sich am Royal College of Music ein, verließ es jedoch wieder noch vor Abschluß des ersten Studienjahres. Stattdessen konzentrierte er sich ganz auf den Volkstanz und wurde ein professioneller ›Morris Dancer‹ – vielleicht sogar der einzige, den es überhaupt jemals gab. Die Archive der ›English Folk Dance and Song Society‹ enthalten Filmmaterial von Butterworth, wie er mit Cecil Sharp und Maud Karpeles Volk-stänze aufführt. Er kam viel herum, um Tanz-Techniken vorzustellen, und veröffentlichte auch Bücher zu diesem Thema. Dessen ungeachtet blieb die Musik der Hintergrund all dieser Interessen. Sein Schaffen war zwar nicht umfangreich (er war ein gründlicher Arbeiter, der seine Sachen immer wieder revidierte), doch andererseits hinterließ er weit mehr Werke als heute noch bekannt. Als im August 1914 der Krieg ausbrach, schloß sich Butterworth Kitcheners ›New Army‹ an und begann, sein Lebenswerk zu ordnen. Dabei zerstörte er wahrscheinlich etliche Frühwerke wie die Barcarolle. Später wurde er Unteroffizier in der Kompanie B, 13. Bataillon, Durham Light Infantry, bestehend überwiegend aus Mienenarbeitern, deren Gesellschaft er mochte. Später wurde er zum Lieutenant befördert, allerdings erst, nachdem er in den Kriegsberichten lobend erwähnt, für einen Orden vorgeschlagen worden war und schließlich für sein Handeln bei Pozières am 19. Juli 1916 auch einen bekommen hatte. In der Nacht zum 5. August 1916 befehligte er einen Angriff auf jene deutsche Linie, die die Briten als ›Munster Alley‹ (Monster-Allee) kennen, und bekam dafür zum zweiten Mal das Verdienstkreuz. Doch noch vor der Abenddämmerung des gleichen Tages tötete ihn eine Kugel in den Kopf. Er war kaum 31 Jahre alt. Der hastig bestattete Körper wurde nach dem Krieg nie gefunden. Heute zählt sein Name zu denen der 74.000 an der Somme Gefallenen auf dem Ehrenmal von Thiepval.

Two English Idylls (Zwei englische Idyllen)

Dies beiden Miniaturen sind die frühest erhaltenen Orchesterwerke von Butterworth, stammend von 1910/11. Sie erklangen erstmals am 8. Februar 1912 in der Oxford Town Hall in einem Konzert des Oxford University Musical Club, geleitet von Hugh Allen, dem Organisten des New College. Die Aufführung wurde so gut aufgenommen, daß das zweite Idyll als Zugabe nochmals erklang. Die Times nannte die Komposition »höchst vielversprechend, mit großer Eigenständigkeit der Harmonik und Instrumentierung, von einzigartig frischer und feinsinniger Bildhaftigkeit.« Das ›kleine Orchester‹ von Butterworth beschäftigt immerhin verdoppelte Holzbläser einschließlich Piccolo-Flöte, vier Hörner, Pauken, Triangel, Harfe und Streicher. Die Orchestrierung ist besonders gekonnt und delikat, und auch die Durchführung des schlichten Themenmaterials ist durchweg von hoher Qualität.

Das erste Idyll verwendet drei Volkslieder aus der Grafschaft Sussex. Das von der Oboe allegro scherzando angekündigte erste davon folgt einem in vielen Varianten bekannt gewordenen Song namens Dabbling in the dew. Auch das zweite wird (bei Studierziffer D) von der Oboe eingeführt, nunmehr più moderato; es handelt sich um Just as the tide was flowing, von Butterworth im April 1907 aufgezeichnet. Eine lebendigere molto vivace Sektion (F) enthüllt die dritte Melodie, Henry Martin (aufgezeichnet von Butterworth im Juni 1907), zunächst in der Klarinette, dann Flöte und Fagott. Nach einiger allgemeiner Verarbeitung hört man in den Streichern (bei L) eine Fortissimo-Version von Just as the tide; eine Höhepunkt wird erreicht, doch plötzlich wird alles still, und Oboe und Flöte teilen sich das Anfangsthema (3 Takte nach N). In den Schlußtakten tauchen zwar einige geschäftige Streicherfiguren von früher auf, doch das Stück endet friedvoll. Das zweite Idyll hat nur ein Thema, den Song Phoebe and her dark-eyed sailor, von Butterworth erstmals aufgezeichnet in Sussex im April 1907. Im Gegensatz zum vorausgehenden Idyll ist dieses zweite langsamer, weicher und verinnerlichter gesetzt, wunderschön instrumentiert, und wiederum mit der Haupt-Melodie in der Oboe, begleitet von zwei Fagotten. Ungeachtet des zärtlich-lyrischen Charakters bewegt sich die Musik doch auf einen Höhepunkt von einiger Weite und Kraft zu, bevor das Werk ruhig ausklingt. Gegen Ende spielt eine Solo-Violine eine verzierte Variante der Melodie im Kanon mit einer Solo-Klarinette (bei G).

London hörte die Two English Idylls erstmals bei einem Promenadenkonzert in der Queen’s Hall am 31. August 1919, dirigiert von Sir Henry Wood, der sie bei gleicher Gelegenheit zwei Jahre später wiederholte. Butterworths Vater, Sir Alexander, wohnte jener Wiederholung bei und schlug vor, daß man vielleicht bei zukünftigen Aufführungen die Reihenfolge vertauschen sollte. Wood stimmte zu, und tatsächlich diskutiert auch ein Artikel von Hugh Allen aus dem Jahr 1917 (Times Literary Supplement, 26. April) die beiden Sätze in umgekehrter Folge.1922 sorgte Adrian Boult für eine weitere Vebreitung der Idyllen, in Prag am 5. Januar und in Barcelona am 26. Mai (allerdings nur Nr. 1); beide Aufführungen wurden warm aufgenommen. Die Idyllen erschienen 1920 bei Stainer and Bell; eine Bearbeitung für zwei Klavier von John Mitchell kam erst 1999 bei Modus Music heraus. Dessen ungeachtet werden die Two English Idylls bis heute weitgehend vernachlässigt, obwohl es aus den Siebziger Jahren sogar drei Schallplatten-Einspielungen und zwei CD-Aufnahmen aus den späten Achtzigern und je eine weitere von 1993 und 2003 gibt.

Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad

Erste Entwürfe zu diesem wohl besten Werk von Butterworth entstanden anscheinend bereits in seinem Lehrjahr am Radley College (1909/10). Wie bei ihm üblich überarbeitete er es immer wieder, so daß die Partitur nicht vor 1911 abgeschlossen wurde. Zwei weitere Jahre vergingen bis zur Uraufführung, und nochmals vier bis zur Veröffentlichung. Nicht einmal der Titel war problemlos: Butterworth bevorzugte ursprünglich The Land of Lost Content, sodann The Cherry Tree, bevor der heutige Name endgültig feststand. Noch im Juni 1913 – vier Monate vor der Premiere – hieß es The Cherry Tree, obwohl das Stück, wie der Komponist bemerkte, »mit Kirschbäumen etwa genauso viel oder wenig zu tun hat wie mit Käfern.« Ungeachtet der langen Zeit zwischen Entwurf und Veröffentlichung wurde die Rhapsodie von den Orchestern nie vernachlässigt und wird heute als wohl Butterworths größtes Stück geschätzt. Inspiriert wurde sie offensichtlich durch seinen ersten Housman-Zyklus, Six Songs from ›A Shropshire Lad‹, doch zeigt die Rhapsodie trotz vieler Vorzüge des Liederzyklus doch noch ein höheres Niveau. Im Programm zur ersten Londoner Aufführung beschrieb Butterworth sie als »Eine Art Orchester-Epilog zu meinen beiden Liederzyklen nach A Shropshire Lad. Das thematische Material stammt hauptsächlich aus Loveliest of trees, hat aber sonst keine weitere Verbindung zu den Worten dieses Liedes. Die Rhapsodie soll vielmehr vor allem das Heimweh des ›Shropshire Lad‹ in seinem Exil ausdrücken.« Die elegische und zugleich pastorale Musik entsprach sehr dem damaligen Zeitgeist, ein Beispiel für das, was Christopher Palmer »einen Trauergesang auf das Ende des guten Lebens, auf jene ... glorreichen Sommer der Edward-Jahre« nannte. Die eindringlichen und ausdrucksvollen musikalischen Gedanken der Rhapsodie berühren vielleicht noch mehr, wenn man bedenkt, daß der Krieg in nur wenigen Jahren bereits etliche Freunde des Komponisten dahingerafft hatte.

Die Rhapsodie beansprucht ein großes Orchester, obwohl die Instrumentierung ausgesprochen delikat ist und Butterworth das Tutti nur im zentralen Höhepunkt des Werkes fordert. Es beginnt mit einem a-moll-Akkord der gedämpften Streicher, über der sich eine klagende Viertonfigur in Terzen alternierend zwischen Bratschen und Klarinetten aufschwingt. So entsteht unmittelbar eine Szene pastoraler, trauernder Sehnsucht, äußerst bedachtsam instrumentiert und dynamisch schattiert, welche noch Ernest Moeran in den Eröffnungstakten seiner First Rhapsody von 1922 beeinflußte. Dann erklingt das erste Zitat aus Loveliest of trees (2. Takt nach A), in der gleichen Tonart wie das Lied selbst. Die Musik wird inniger, reicher instrumentiert, beruhigt sich jedoch bald wieder, um in den Streichern eine neue Idee einzuführen (bei D). Holzbläser treten hinzu, und rasch baut sich ein leidenschaftlicher Höhepunkt auf, den Michael Kennedy mit einer Stelle im Finale der Pastoral Symphony von Vaughan Williams in Verbindung brachte, wo Streicher und Holzbläser einen dramatisch-eindrücklichen Dialog führen; seiner Meinung nach bilden diese Takte höchstwahrscheinlich Vaughan Williams’ musikalischen Grabstein von Butterworth. Es ist dieser Höhepunkt, wo Butterworth ein einziges Mal alle beteiligten Kräfte vereinigt (bei F). Danach werden frühere Motive neuartig und farbenreich instrumentiert durchgeführt; die Harfe hat zunehmend mehr zu tun, und es gibt sogar eine Stelle für Bassklarinette und dreistimmig geführte Kontrabässe allein (nach L). Die klagende Anfangsfigur erscheint schließlich im Solo-Horn (vier Takte nach K), und in der auf den Anfang zurückgreifenden Coda sind die Rollen von Klarinetten und Viola gegenüber dem Anfang vertauscht. Als genialen Nachtrag zitiert Butterworth noch das letzte seiner Bredon Hill Lieder, ›With rue my heart is laden, for golden friends I had‹, in der Solo-Flöte acht Takte vor Schluß, bevor die Streicher mit einem abschließenden a-moll-Akkord verklingen.

Von allen überlebenden Orchesterwerken Butterworths hat nur die Rhapsodie – von kurzen Anklängen abgesehen – keine unmittelbare Verbindung zum Volkslied, obwohl dieWurzeln seines Stils eindeutig in der Musiktradition seiner Heimat gründen (zum Beispiel das dorisch färbende Fis gleich im dritten Takt). Ein wichtiges Merkmal der Rhapsodie ist seine meisterhafte Orchestrierungskunst, die ebenfalls wenig auf teutonische Vorbilder zurückgreift, auch wenn die Durchführung im Mittelteil for der zentralen Klimax vielleicht Caikovskij einiges verdankt. Die Rhapsodie wurde am 2. Oktober 1913 beim Leeds Festival vom London Symphony Orchestra unter Arthur Nikisch uraufgeführt – übrigens am Nachmittag des Tages, an dem später auch Elgars Falstaff erstmals erklang. Der ältere Komponist konnte Butterworths Werk allerdings nicht hören, da er mit seiner Familie und Freunden einen Erholungsausflug nach Fountains Abbey machte. Zuhörer und Kritiker nahmen die Rhapsodie begeistert auf. Henry Hadow sprach von einer »neuen Stimme in der englischen Musik«, der Komponist Cyril Rootham von »bemerkenswerter Qualität und erstklassigem Handwerk« der Komposition, und Edward Dent hatte »keinen Zweifel, das George der einzige Jüngere wäre, den man ... Vaughan Williams ... an die Seite stellen« könnte. Andere Dirigenten und Orchester nahmen das Stück rasch in ihr Repertoire. Die Londoner Erstaufführung folgte am 20. März 1914 in der Queen’s Hall mit dem Queen’s Hall Orchestra unter Geoffrey Toye in einem Konzert der Reihe ›Modern Orchestral Music‹ von Bevis Ellis. Dabei wurde auch The Banks of Green Willow erstmals in London aufgeführt, drei Wochen nach dessen Premiere in Cheshire. Auch nach fast 100 Jahren bleibt diese Rhapsodie eins der beliebtesten britischen Orchesterwerke des 20. Jahrhunderts. Es hat überdies verschiedene Werke aus den Zwanziger Jahren anderer britischer Komponisten geprägt, insbesondere Ralph Vaughan Williams (Pastoral Symphony), Gerald Finzi (Severn Rhapsody), Ernest Moeran (First Rhapsody) und einige Frühwerke von Herbert Howells. Interessant ist außerdem, daß vier Takte der Rhapsodie sogar noch in einer heute kaum mehr bekannten Komposition von 1943 zitiert werden, in der Elegy for Strings von Harold Truscott.

The Banks of Green Willow

Butterworths letztes vollendetes Orchesterwerk stammt von 1913 und ist für kleineres Orchester als Rhapsodie instrumentiert – doppeltes Holz, zwei Hörner, Trompete, Harfe und Streicher, sogar noch weniger als in den Two English Idylls. Als gleichsam drittes Folksong-Idyll ist The Banks of Green Willow in verschiedener Weise mit den beiden früheren verbunden – seine kürzere Länge als die Rhapsodie, die einfallsreiche Verwendung von Folksong-Material, die bogenförmige Struktur und die kleine Orchestrierung. Allerdings zeigt das zwei oder drei Jahre nach den English Idylls entstandene Werk noch reifere Technik und reichere Harmonik, was ihm eine geradezu versunkene Schönheit verleiht. Der Komponist beschrieb es als »musikalische Illustration der gleichnamigen Folk-Ballade.« Neben ihr verwendet er ein weiteres Volkslied – Green Bushes – und noch ein originales Thema. Die beiden Folksongs zeichnete Butterworth wiederum im Sommer 1907 in Sussex auf.

Die Solo-Klarinette prägt die pastorale Szene mit dem Titelthema, und nach einer Durchführung der Streicher spielen Flöte und Oboe allmählich eine aktive Rolle. Die Stimmung schlägt um bei einem Abschnitt im 3/2-Takt (Maestoso; bei C), in dem ein Originalthema verarbeitet wird, mit prominenten Hörnern, hinleitend zu einer bewegten Streicherpassage (D), die im zentralen Höhepunkt des Werkes weiter verarbeitet wird – neben zwei Takten des Anfangsthemas. Die Musik beruhigt sich schnell, um Green Bushes einzuführen, erst in der Solo-Oboe (F), dann in der Flöte, von Harfen-Arpeggien begleitet, wie in englischer Pastoral-Musik weit verbreitet (G). Einer langsamen Passage für Streicher allein (H) folgen in den Schlußtakten Oboe und Horn, die die bewegtere Passagen von früher wieder aufgreifen, doch nun in einer weit ruhigeren Atmosphäre.

Die Uraufführung von The Banks of Green Willow fand am 27. Februar 1914 statt; Adrian Boult dirigierte ein Orchester, zusammengestellt aus je 40 Mitgliedern des Hallé und des Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, in West Kirby, einer Stadt auf der Wirral-Halbinsel, wo Boults Eltern damals lebten. Dies war tatsächlich das erste Konzert des damals jungen Dirigenten mit einem professionellen Orchester, bei dem auch die britische Erstaufführungvon Hugo Wolfs Italienischer Serenade erklang – eine beachtliche Leistung für ein Dirigier-Debut! Die Londoner Premiere drei Wochen später scheint die letzte Gelegenheit für Butterworth gewesen zu sein, seine eigene Musik zu hören. Es gibt von dem Werk vier Bearbeitungen – eine für Blasorchester (1973) von Phillip Brookes (unveröffentlicht), für Klarinette und Klavier von Robin de Simet (Fentone 1987), für Klavier allein von John Mitchell (Thames 1993), und eine für Blockflöten-Orchester von Denis Bloodworth (ob diese Bearbeitung veröffentlicht wurde, ist nicht bekannt).

George Butterworth und A. E. Housman

Die bedeutendsten Lieder von Butterworth findet man unter seinen beiden Liederzyklen nach A. E. Housmans A Shropshire Lad: die Six Songs und Bredon Hill and Other Songs. Die schlichten, direkten Verse sprachen viele Komponisten an, und nicht nur aus England: Tatsächlich interessierten sich einige amerikanische Komponisten sogar noch vor ihren englischen Kollegen für Housman; einer davon schrieb an den Dichter, fragte um die Erlaubnis zur Vertonung an und bot sogar ein Honorar. Die Erlaubnis wurde gewährt, das Honorar nicht angenommen ... Die ersten Vertonungen in England (zehn Lieder von Arthur Somervell) erschienen 1904, acht Jahre nach der Erstveröffentlichung der Gedichte. Darin geht es um einen Protagonisten namens Terence Hearsay, ein junger Mann aus Shropshire, der nach London ging, um dort wie Housman im Exil zu leben. Die Sammlung enthält 63 kurze Gedichte, in denen der Jüngling unter anderem als Soldat, Farmer, Krimineller und Liebhaber erscheint. Die nostalgischen Verse inspirieren selbst noch heute, im 21. Jahrhundert, unzählige Komponisten! Bei der aesthetischen Betrachtung all dieser Housman-Vertonungen sind sich die meisten Kommentatoren freilich darin einig, daß nur selten jemand die Schlichtheit und Unmittelbarkeit der Lieder von Butterworth erreichte, auch wenn die sehr individuellen Lieder von Ivor Gurney und C. W. Orr besonderen Anklang fanden. Doch die einfachen, delikaten Lieder von Butterworth scheinen den Versen Housmans im Ausdruck am ehesten zu entsprechen, und es ist diese im wahrsten Sinn perfekte Übereinstimmung von Musik und Wort, die Hörer und Musiker gleichermaßen anzieht. Die elf Houseman-Vertonungen von Butterworth waren ursprünglich zusammenhängend konzipiert, wurden allerdings anläßlich ihrer Veröffentlichung später in zwei Gruppen aufgeteilt.

Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad

I. Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad‹

Dieser erste Zyklus, der Butterworths Namen berühmt machte und als Klassiker unter den britischen Liedvertonungen des 20. Jahrhunderts gilt, wurde 1911 beendet und am 16. Mai des gleichen Jahres uraufgeführt, in einem Treffen des Oxford University Musical Club, organisiert von Adrian Boult; der Bariton J. Campbell McInnes sang begleitet vom Komponisten am Klavier. The lads in their hundreds wurde ausgelassen, allerdings waren auch vier Lieder des späteren Bredon Hill-Teils (mit Ausnahme von On the idle hill of summer) enthalten. Die Londoner Premiere der Six Songs folgte am 20. Juni 1911 in der Aeolian Hall; McInnes wurde diesmal von dem Komponisten und Dirigenten Hamilton Harty begleitet. Das Publikum bestand auf einer Wiederholung des hier wohl erstmals erklungenen The lads in their hundreds. Die Lieder sind ›V. A. BARK.‹ gewidmet. Dabei handelt es sich um Victor Annesley Barrington-Kennett, einem Jahrgangsgenossen von Butterworth in Eton und Oxford, dessen Familie in dem Haus in Chelsea lebte, das die Butterworths 1910 gekauft hatten. Auch er sollte 1916 an der französischen Front fallen. In den frühen sechziger Jahren wurden die Six Songs von Lance Baker instrumentiert, dem Sohn der Komponistin und Dirigentin Ruth Gipps. Im Ganzen blieb Baker dem Stil der Rhapsodie treu. Die hier vorgelegte Ausgabe enthält eine neue Orchestrierung aller elf Lieder durch Phillip Brookes, zwar für kleineres Orchester als bei Baker, doch die delikate Natur von Butterworths Handschrift erfolgreich erhaltend.

Loveliest of trees

Dies ist das wohl am häufigsten vertonte Gedicht von Housman; 1976 waren bereits mindestens 35 davon bekannt. Die Vertonung von Butterworth ist eine der bekanntesten und besten; sie bildet auch die Grundlage für die Rhapsodie. Das Gedicht handelt von dem Zwanzigjährigen, der einen blühenden Kirschbaum bewundert und zugleich das allzu rasch verstreichende Leben bedauert, auch wenn ihm sicherlich noch gut 50 Jahre bleiben würden, um sich seine Bewunderung zu bewahren. Die feine melodische Kontur der Introduktion zeichnet vielleicht eine fallende Kirschblüte nach, setzt eine ruhige, pastorale Atmosphäre und leitet in die eindringliche vokale Linie, die die Basis der Rhapsodie bildet. Im ersten Vers verwendet Butterworth den für ihn ungewöhnlich weiten Umfang einer kleinen Dezim. Der zweite Vers (Takt 22), in der der Jüngling den Fortgang der Jahre reflektiert, wird nur sparsam begleitet, während fließende Arpeggien den dritten untermalen (Takt 32), erinnernd an die erste Arabeske von Claude Debussy für Klavier (1888) in der gleichen Tonart E-Dur. Der Epilog (Takt 43) entwickelt das Thema in für Butterworth charakteristischen Terzen.

When I was one-and-twenty

In diesem schlichten Lied verwendete Butterworth eine traditionelle, dorische Melodie, deren Identität ungeklärt bleibt, auch wenn verschiedentlich vorgeschlagen wurde, ein Lied namens Through Moorfields heranzuziehen. Er vertonte sensibel die Geschichte des sorglosen Jünglings, der sich verliebt und ein Jahr später verzweifelt; die Wiederholung der Worte ›’tis true‹ am Ende erzeugt eine angemessene Unterstreichung dieser Traurigkeit. Nur C. W. Orr, dessen Housman-Vertonungen ebenfalls geschätzt werden, der aber kein großer Bewunderer von Butterworth war, geißelte dieses Lied für die Verwendung der »gräßlich schwachen Melodie«.

Look not in my eyes

Dies Lied ist ähnlicher Stimmung, wenn auch mit besonderem Bezug zum Mythos des selbstverliebten Narcissus. Der volkstümliche Charakter bleibt durchgängig, mit unvermeidbar erniedrigten Septen, doch zugleich sorgt der unablässige 5/4-Takt dafür, daß daraus nicht nur ein weiteres, gerade gestricktes Liedchen wird. Die ersten drei Lieder lassen sich in ihrer Lyrik und ihrem schlichten Charme zusammengruppieren. Die folgenden drei sind von dramatischerer Natur.

Think no more, lad

Die Originalhandschrift gibt Einblick, wie viele Änderungen Butterworth bis zur gedruckten Version stets vornahm: Der zweite und dritte Vers wurden drastisch verändert, die Grundtonart von g-moll zu gis-moll verschärft. Die rastlose Stimmung des Gedichts fängt die Musik gut ein, und die synkopierten Akkorde (Vers 2, Takt 151) und raschen Arpeggien (Vers 3, Takt 170) machen die Begleitung komplexer als irgendwo sonst in diesem Zyklus. Butterworth wiederholt den ersten Vers nach dem zweiten, mit gleicher Linienführung bis zum Höhepunkt ›falling sky‹ (Takt 180), doch mit einer virtuoseren Begleitung und für den Komponisten vergleichsweise geringer Wortmalerei – ein beeindruckender Schluß.

The lads in their hundreds

Die Botschaft des Liedes ist schlicht: Die Jünglinge gehen vielleicht zum letzten Mal zum jährlichen Markt von Ludlow – ein schönes Beispiel für die ironischen Bezüge zwischen Butterworths eigenem Leben und den von ihm zur Vertonung erwählten Gedichten. Die schwungvolle Weise, fast unausweichlich stets in zusammengesetzten Metren, paßt perfekt zu den Worten. Hier hat der Komponist wiederum die Grundtonart nachträglich verändert, von ursprünglich F-Dur zu Fis-Dur.

Is my team ploughing?

Dieses bemerkenswerte Lied ist das eigentliche Juwel nicht nur des Zyklus, sondern aller Lieder von Butterworth. Nach den natürlich gut gemachten, geradlinigen Vertonungen setzt dieses besondere Lied sofort einen Akzent durch seine schiere Schlichtheit und extrem berührende Qualität. Hier wird ein Dialog zwischen einem Verstorbenen und seinem noch lebenden Freund passend portraitiert. Housmans acht Verse wechseln zwischen diesen beiden Charakteren hin und her, und Butterworth ist sehr darauf bedacht, jeden Vers strophisch zu behandeln, ungeachtet des Lied-Endes. Die fragenden Verse des Toten sind einfach vertont, stets Pianissimo und unterstützt von langen, absteigenden Neben-Akkorden, möglicherweise abgeschaut im Streichquartett von Edvard Grieg. Die Antworten des Lebenden sind völlig anders, eine tiefere Linienführung, rascher und lauter als zuvor, und mit langen Stamm-Akkorden begleitet. Das eigentliche Meisterstück findet sich ganz am Schluß: ›I cheer a dead man’s sweetheart; Never ask me whose‹ (Takt 272). Die Worte sind die des Lebenden, doch die Musik der Schlußphrase, nun leise und weich, ist die des Toten, unterstrichen durch die Neben-Akkorde. Die letzte Frage des Toten bleibt also unbeantwortet, ein Effekt, der durch den unaufgelösten moll-Allord mit hinzugefügter kleiner Sext am Ende noch verstärkt wird, wenn auch Ernest Newman überraschenderweise glaubte, daß »Butterworth darin versagte ..., eine angemessene musikalische Entsprechung für das Ende des Gedichts zu finden,« und dieses Lied ironisch als »eine Art telephonisches Ferngespräch zwischen den beiden Männern« bezeichnete.

2. Bredon Hill and Other Songs

Dieser Zyklus erschien 1912, ein Jahr nach den Six Songs, und war offenbar ein sofortiger Erfolg. Allgemein waren die Besprechungen voll des Lobes für diese bezaubernden und originellen Lieder mit ihren Schätzen an melodischer und harmonischer Schönheit. Die Begleitungen sind allerdings meist komplexer als im ersten Zyklus, namentlich im besten dieser Lieder, On the idle hill of summer.

Bredon Hill

Auch dieses sehr bekannte Gedicht hat etliche Komponisten inspiriert, insbesondere Peel, Somervell und Vaughan Williams, deren Vertonungen immer wieder miteinander verglichen wurden. Die wiederholte Erwähnung von Glocken in dem Gedicht macht es für eine Vertonung besonders anziehend, doch Butterworth tat sein Möglichstes, diese Anklänge nicht allzu deutlich werden zu lassen. Ein Gedicht solcher Länge, mit sieben Stanzen, benötigt eine gewisse Vielfalt der Tonsprache, wovon Butterworth sich dramatische Vorteile verschaffte (Peels volkstümliche Bearbeitung dagegen ist im Grunde strophisch). Das Gedicht beschreibt, kurz gefaßt, Liebe, Hoffnung und Trauer, mit Hinweisen auf Glocken anläßlich verschiedener Gelegenheiten – Sonntag, Hochzeit, Bestattung. (Housman spielt hier auf das Gedicht The Bells von Edgar Alan Poe an.) Es handelt sich um eine der komplexesten Vertonungen von Butterworth, die in besonderem Maße auf wiederholte Strukturen zurückgreift, zum Beispiel die winzige Einleitungsfigur und die fließende Achtelbegleitung. Vielfalt entsteht durch die Vermeidung strophischer Vertonung und absteigende Halbton-Rückungen von Tonarten. Der letzte Vers, wieder in F-Dur, enthält bei den Worten ›O noisy bells, be dumb; I hear you, I will come‹ den Höhepunkt des Liedes, wo Butterworth interessante Harmonien, ein plötzliches Moll und wirkungsvoll die Ganztonleiter einsetzt.

Oh fair enough are sky and plain

Diese Vertonung erscheint im Autograph an erster Stelle und stammt vielleicht schon von 1909. Es handelt sich um ein weiteres Lied über den Narzißmus, ist aber unproblematisch. Die Begleitung ist leicht, bestehend aus weitgeht isolierten Akkorden oder Akkord-Paaren, ausgenommen der zweite Vers, wo die Stimme der gekräuselten Begleitung der ›pools and rivers‹ (Takt 416) untergeordnet ist.

When the lad for longing sighs

Die Volkstümlichkeit und der sanfte Lyrizismus dieses Liedes erinnern an Look not in my eyes, und die drei kurzen Verse bilden ein Ganzes von berückender Schlichtheit und geradliniger Melodik und Harmonik.

On the idle hill of summer

Die Tatsache, daß dieses Lied nicht im Originalmanuskript der Housman-Lieder erscheint, könnte nahelegen, das Butterworth es nachträglich komponiert hat. Es ist ein weiteres Beispiel für den ironisch-autobiographischen Unterton dieser Lieder: Der Dichter hört aus der Ferne Soldaten marschieren, während er auf einem Hügel liegt und träumt. Nachdem er die Verrücktheit des Krieges bedacht hat, zieht er selbst in den Krieg. Die oft komplexe Begleitung bleibt manchmal statisch, mit wiederholten, pochenden Sext-Akkorden, die ›the steady drummer drumming like a noise in dreams‹ repräsentieren, während die Akkorde auf seltsame Weise an einen schwülen Sommertag erinnern. Die Melodie ist im ersten und dritten Vers meist aus Noten des A-Dur-Akkords mit hinzugefügter Sext gebildet, während der zweite Vers (T. 487) sofort neue Ideen auswirft, unter Verwendung von Dominant-Non- und Tredezim-Akkorden. Der vierte und letzte Vers (T. 515) ist bemerkenswert, weil weitaus lebendiger, mit einer geschäftigen Begleitung, die Militärsignale (›Bugles‹) und ›the screaming fife‹ imitiert und zu dem dramatischen Ausbruch ›Woman bore me, I will rise‹ führt (Takt 521). Einige Vertonungen dieses Gedichtes wie die von Somervell lassen das Klavier brutal enden, doch Butterworth verringert die Begleitung nach und nach zu einem pp morendo in der Coda, die den eröffnenden Trommel-Rhythmus wiederkehren läßt, so daß man die Soldaten und Trommler geradezu vor sich sieht, wie sie allmählich verschwinden. Ein eindrucksvoller Schluß eines wunderbaren Liedes, vielleicht eine der größten Errungenschaften des Komponisten. Die Tonsprache ist hier weit entfernt vom liedhaften Idiom und sehr spätromantisch gehalten.

With rue my heart is laden

Die einfachen, traurigen Stimmungen des Gedichts fassen treffend das Leben des Komponisten zusammen. Das Volkslied wird unaufdringlich begleitet; die Anfangsphrase wird bekanntermaßen am Ende der Rhapsodie A Shropshire Lad zitiert. Wort, Melodie und Begleitung entsprechen einander perfekt, und insgesamt bildet das Lied einen angemessenen Abschluß dieses Zyklus.

Michael Barlow, Tandridge, Surrey, July 2006

Literaturhinweis: Michael Barlow - Whom the Gods Love, the Life and Music of George Butterworth. Toccata Press, London, 1997.

Anmerkungen des Herausgebers zur Anordnung der Lieder

und der Bearbeitung für Orchester

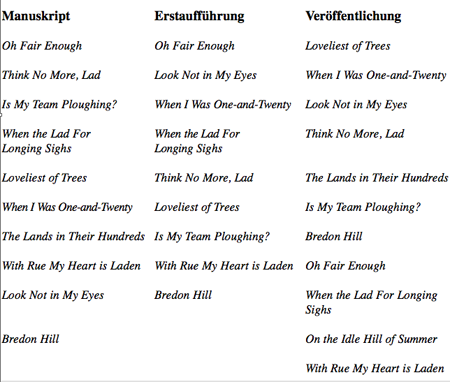

George Butterworth vertonte zwischen 1909 und 1911 elf der 63 Gedichte aus Alfred Edward Housmans A Shropshire Lad. Eins davon, On the Idle Hill of Summer, könnte auch erst später entstanden sein, da es nicht unter den zehn Liedern war, die der Komponist 1912 in Eton aus dem Manuskript aufführte. Butterworth wollte sie ursprünglich geschlossen veröffentlichen, änderte dann jedoch seine Meinung und gab zwei Serien heraus, zunächst die Six Songs from ›A Shropshire Lad‹, dann ›Bredon Hill‹ and Other Songs. Alle elf Lieder sind in dieser Orchesterbearbeitung enthalten, und zwar in der von Butterworth publizierten Reihenfolge. Sie war freilich nicht von Beginn an klar. Die nachfolgende Tabelle vergleicht die Reihenfolge der zehn Lieder im Eton-Manuskript, der Uraufführung von neun der Lieder am 16. Mai 1911 und die die beiden veröffentlichten Serien.

Das soll nun keineswegs nahelegen, das Ausführende die letztwillig publizierte Reihung geflissentlich ignorieren dürfen, die sicherlich Butterworths eigenem letzten Wunsch entspricht. Doch soll unterstrichen werden, daß es einige Unsicherheiten in der Musik gibt, zumal George Butterworth nicht gerade zurückhaltend darin war, seine Meinung zu ändern. Sein trauriger früher Tod, den er in einigen dieser Lieder regelrecht vorgeahnt zu haben scheint, verhinderte vielleicht auch weitere Unwägbarkeiten als wir uns wünschen würden; hätte er allerdings die Gräuel des großen Kriegs überlebt, wüßten wir nun vielleicht mehr über seine eigenen Gedanken hinsichtlich des Zusammenhangs dieser Lieder.

Anmerkungen zur Instrumentierung eines englischen Klassikers

Es gibt keinen expliziten Hinweis darauf, daß George Butterworth jemals selbst an eine Orchestrierung seiner ›Shropshire Lad‹-Lieder gedacht hat. Daher fühlte ich mich durchaus unbehaglich, als ich mit meiner Instrumentierung begann, denn wie auch immer das Ergebnis ausfallen würde, könnte ich doch kaum behaupten, damit den Wünschen des Komponisten gefolgt zu sein. Doch andererseits verbinden sich viele Aspekte dieser Lieder in unserem kollektiven Unbewußten mit Orchesterfarben, allein schon durch des Komponisten eigene Rhapsodie ›A Shropshire Lad‹. Außerdem legt in vielen Liedern, darunter When I was One-and-Twenty, The Lads in Their Hundreds, Is My Team Ploughing? and When The Lad for Longing Sighs, Butterworths zurückhaltende Begleitung eine Orchestrierung weit näher, als es ein überladener Klavierstil tun würde. Es gibt auch Vorbilder: Butterworth selbst orchestrierte seinen dreiteiligen Liederzyklus Love Blows as the Wind Blows, der ursprünglich für Kammermusik-Besetzung geschrieben war (vergl. Butterworth: Vol. II dieser Reihe). Auch sein Freund Vaughan Williams hatte bereits drei seiner Songs of Travel instrumentiert und würde es später auch mit seinen eigenen Housman-Vertonungen tun, On Wenlock Edge von 1909, frühe Zeitgenossen von Butterworths Liedern, im Original für Stimme, Klavier und Streichquartett.

Größe des Orchesters und Wahl der Instrumente

Butterworths Rhapsody ist für großes Orchester, auch wenn der Komponist damit ökonomisch umgeht. Meiner Ansicht nach würde ein derartiges Orchester in diesen Liedern Solisten und Dirigenten mehr Kopfschmerzen bereiten als nötig, wenn es um eine angemessene Balance zwischen Stimme und Orchester geht. Jeder Musiker mehr erhöht zudem die Kosten eines Konzerts, doch ich wollte diese Musik sowohl Amateur- wie auch Profi-Orchestern zugänglich machen. Deshalb habe ich diese Lieder konsequent für kleines Orchester gesetzt, wie auch Butterworth selbst, als er Love Blows instrumentierte, das ich zum Vorbild nahm, ergänzt um eine Trompete sowie eine Harfe, die allerdings optional ist. (Ich habe erst überlegt, sie ganz wegzulassen, aber die Vorteile in O Fair Enough ließen alle anderen Überlegungen verstummen.) Das Schlagzeug ist das gleiche wie in den Two English Idylls: Pauken und Triangel. Es war klar, daß bei einer Instrumentierung der Klavierpart verändert, Akkorde anders verteilt, Figurationen verändert werden mußten, um sich an die Technik der Orchesterinstrumente anzupassen. Andererseits eröffnete sie Möglichkeiten, über die Beschränkungen der zwei Hände eines Pianisten hinauszugehen und einige Feinheiten zu unterstreichen, die im Original nicht offenkundig wurden. Bei solchen Gelegenheiten habe ich mich stets gefragt: »Hätte Butterworth selbst das gleiche schreiben können, ohne die Begleitung gravierend zu ändern?« War die Antwort ja, habe ich solche Veränderungen für gewöhnlich gemieden; war sie nein, habe ich sie möglicherweise vorgenommen. Anders gesagt: Was Butterworth mit Leichtigkeit selbst getan haben könnte, aber nicht tat, verbot sich mir mithin stets von selbst. Man beachte jedoch das Gewicht auf der Leichtigkeit, denn es wäre an vielen Stellen durchaus möglich gewesen, die Musik aufzumotzen, doch nur auf Kosten anderer, wichtiger Details. Es gibt zwar nicht viele Beispiel, aber der Vogelgesang in der Flöte bei Ziffer 20 (›…and hear the larks so high about us in the sky‹) ist ein, wo mir scheint, der Komponist hätte so etwas nicht hinzusetzen können, ohne den Impetus der Arpeggio-Begleitung zeitweise zu verlieren. Andererseits gab es kein explizites Verbot, und so habe ich diese Idee in meiner Orchestrierung ausgearbeitet. All dies ist natürlich keine Rechtfertigung für meine Bearbeitung dieser Lieder. Ich hoffe einzig, daß das Ergebnis Freude bereitet und wir sie vielleicht in einem anderen Licht ganz neu hörend erleben können.

Phillip Brookes, Market Drayton, 2006

Übertragung ins Deutsche: Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, Bremen, 2006 (bruckner9finale@web.de)

English Idylls, Rhapsody, Banks of Green Willow: Aufführungsmaterial erhältlich bei Chester Novello (www.chesternovello.com). Eleven Songs: Aufführungsmaterial erhältlich bei Musikproduktion Höflich, München (www.musikmph.de). Nachdruck von Exemplaren aus der Sammlung Phillip Brookes, Market Drayton.

|

|

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth

(b. 12 Juli 1885, London - 5. August 1916, Pozières)

Volume 1

Works for Orchestra

Two English Idylls

(1910-1911)

Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad

(1911)

The Banks of Green Willow

(1913)

Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad

(1910-1911)

(arranged for voice and small orchestra by Phillip Brookes)

Preface

George Butterworth was one of Britain’s finest musicians during the years leading up to World War One, a conflict which tragically claimed his life. As a composer, he wrote exquisite music for the orchestra in addition to moving and poignant songs, especially to words by A.E.Housman. He was also an important figure in the folksong revival and one of the most talented morris-dancers (folk-dancers) of his day, being responsible for preserving many ancient dances.

He was born in London on 12 July 1885, the son of a lawyer, although he grew up in York (his father was manager of the North-East Railway at the time), before entering Eton and Trinity College, Oxford, where he read Greats (Classics). It was at Eton that he began to show musical promise, producing several compositions that were played by the school orchestra, particularly a Barcarolle for orchestra, long since lost.

At Oxford, he made friends with the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, Adrian Boult (conductor and founder of the BBC Symphony Orchestra) and Hugh Allen (later director of the Royal College of Music).

He joined the newly formed Folk Song Society in 1906 and enthusiastically embraced the fashion for collecting folk songs throughout Britain. He was responsible for preserving about 300 songs - fewer than Vaughan Williams, Grainger or Holst, but still significant. He was music critic for The Times for a short time, and music master at Radley College, Oxfordshire, where he was best remembered for his skill as a cricketer! It was during this time that he began to compose his ‘Shropshire Lad’ songs.

He entered the Royal College of Music in 1910, but left before he had completed a full year. He concentrated instead on folk dancing, becoming in effect a ‘professional’ morris dancer (almost the only one there has ever been). The archives of the English Folk Dance and Song Society include film footage of Butterworth, with Cecil Sharp ad Maud Karpeles, performing folk dances. He travelled widely, demonstrating the technique of folk dancing, and published books of dances.

Music nevertheless remained the backdrop to all these interests. His output was never high (he was a fastidious composer, who habitually revised his work), but he completed more music than we now know. When war broke out in August 1914, Butterworth volunteered to join Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ and began to set out the stall of his life’s work; in the process, he probably destroyed several early works, including the Barcarolle.

He was eventually assigned the role of Subaltern in B Company, 13th Batallion, Durham Light Infantry, which was largely made up of miners, whose company he enjoyed. He was later temporarily promoted to Lieutenant, but not before he had been mentioned in dispatches, recommended for one Military Cross and awarded another for his actions at Pozières on 19 July 1916. On the night of 4-5 August 1916 he led an attack on part of the German line known to the British as ‘Munster Alley’, for which he won the Military Cross a second time. But just before dawn he was shot and died of a single bullet to the head; he was barely 31 years old. He was hastily buried and his body was never recovered after the war, so that today his name is one of the 74,000 inscribed on the memorial at Thiepval, listing those young Britons who died on the Somme and who have no known resting place.

Two English Idylls

These two miniatures comprise Butterworth’s earliest surviving work for orchestra, and date from 1910-1911. Their premiere was given on 8 February 1912 in Oxford Town Hall, at a concert of the Oxford University Musical Club; the conductor was Hugh Allen, organist of New College. This performance was well received, with the second Idyll being encored. The Times commented that the work revealed “ the highest promise, showing great individuality of harmony and orchestration, and a singularly fresh and subtle imaginativeness”. Although styled for “small orchestra”, Butterworth employs double woodwind (plus piccolo), four horns, timpani, triangle, harp and strings. The orchestration is particularly fine and delicate, while the treatment of the basically simple thematic material is of a high quality throughout.

The first Idyll makes use of three folk tunes from the county of Sussex. The first, announced by the oboe, Allegro scherzando, is derived from a well-known song with many variants, Dabbling in the dew. The second is also introduced by the oboe, Più moderato; it is Just as the tide was flowing (rehearsal letter D) and was collected by Butterworth in April 1907. A livelier section, Molto vivace (F), reveals the third tune, Henry Martin (collected by Butterworth in June 1907), played first by clarinet, then by flute and bassoon. After general development, a fortissimo version of the Just as the tide is heard in the strings (L); a climax is reached, then suddenly all goes quiet, with oboe and flute sharing equally the opening theme (three bars after N). In the final bars, busy string figures from earlier recur, and all ends peacefully.

The second Idyll uses only one main theme, Phoebe and her dark-eyed sailor, first collected by the composer in Sussex in April 1907. Compared with its predecessor, this is a slower, softer and more contemplative piece of writing, beautifully scored, and again with solo oboe announcing the tune, accompanied by two bassoons. Although the main characteristic of this piece is of a gentle lyricism, the music does move towards a climax of some breadth and power, before a quiet ending. Towards the close, a solo violin plays a decorated version of the tune in canon with a solo clarinet (G).

London first heard the Idylls at a Queen’s Hall Prom on 31 August 1919, conducted by Sir Henry Wood, who again performed them two years later at the same venue. Butterworth’s father, Sir Alexander, attended the latter concert and suggested to Wood that the order of the Idylls should be reversed in future performances. Wood agreed, and, in fact, in a 1917 article by Hugh Allen (Times Literary Supplement, 26 April), the writer does discuss them in reverse order. In 1922, Adrian Boult introduced the Idylls further afield, in Prague on 5 January and in Barcelona (first Idyll only) on 26 May, both performances being well received. The Idylls were published in 1920 by Stainer and Bell; an arrangement for piano duet by John Mitchell appeared in 1999, published by Modus Music.

Today the Idylls remain comparatively neglected, although three recordings came out during the 1970s, two in the late 1980s, one in 1993 and one in 2003.

Rhapsody: A Shropshire Lad

Sketches for this work, Butterworth’s finest achievement, were most likely begun during the year he taught at Radley College (1909-1910). In his customary manner, a long time was spent carefully revising the work so that the final score was not ready until 1911. Another two years passed before the first performance, and four more before publication. Even the title proved problematical. Butterworth first favoured The Land of Lost Content, then The Cherry Tree before settling on its final name. By June 1913 – four months before the premiere – it was still called The Cherry Tree, the title having, according to the composer, ‘no more concern with cherry trees than with beetles’.

In spite of the long period from conception to publication, the Rhapsody has proved, over the decades, to be Butterworth’s greatest work and has never been neglected by orchestras. The inspiration obviously sprang from the first Housman song-cycle, Six Songs from “A Shropshire Lad”, but there is no doubt that, notwithstanding many fine points in the vocal work, the Rhapsody shows evidence of an even greater talent. In the programme note for the first London performance, Butterworth described the work as ‘[being] in the nature of an orchestral epilogue to [my] two sets of Shropshire Lad songs. The thematic material is chiefly derived from the melody of … Loveliest of trees, but otherwise no connection is to be inferred with the words of the song. The intention of the Rhapsody is rather to express the home-thoughts of the exiled “Shropshire Lad”’.

The elegiac and pastoral music thus created was very much of its time, an example of what Christopher Palmer called ‘a threnody for the passing of the good life, … for those … glorious Edwardian summers’. The poignant and expressive ideas in the music of the Rhapsody are all the more moving when one considers that, within a few years, war had claimed its composer and many of his friends.

The Rhapsody requires large orchestral forces, although one outstanding feature of the work is the delicacy of much of the orchestration, Butterworth employing his full resources only in the central climax. The work opens with a hushed A minor chord on muted strings, above which a haunting four-note figure in thirds alternates between violas and clarinets. Immediately a scene of pastoral, elegiac wistfulness is portrayed, with carefully conceived orchestration and dynamic shading, an effect influencing Ernest Moeran in the opening bars of his First Rhapsody of 1922. Then follows the first quotation from Loveliest of trees (second bar of A), in the tonality of the song. The music grows more intense, with fuller scoring, but soon quietens to introduce a new idea in the strings (D). Woodwind join in, and the music quickly builds to a passionate climax, which Michael Kennedy compares to a passage in the finale of Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral Symphony, where strings and woodwind have a dramatically intense dialogue; he suggests these bars of Vaughan Williams might almost be Butterworth’s memorial. It is at this climax that Butterworth, for the only time, uses all his resources (F). Thereafter, earlier themes are developed in new ways and with colourful orchestration; the harp becomes more prominent, and there is even a very brief passage for bass clarinet, accompanied solely by double basses in three parts (from L). The haunting figure heard at the beginning appears on a solo horn (four after K) and, in the coda, clarinets and violas reverse their initial roles. As a final masterstroke, Butterworth quotes the opening of the last song of his Bredon Hill cycle, ‘With rue my heart is laden, for golden friends I had’, on a solo flute (eight bars from the end), before strings fade away on the final A minor chord.

Of all Butterworth’s surviving orchestral works, only the Rhapsody has no direct connection with folksong, yet the origins of his style are all too clearly derived from the traditional music of his native land (an example of this is the F sharp in bar 3, obviously derived from the Dorian mode).His absolute mastery of the orchestra is an important feature of the Rhapsody and owes little to Teutonic influences, although the development of the middle section, leading to the central climax, possibly owes something to Tchaikovsky.

The Rhapsody received its premiere on 2 October 1913, during the Leeds Festival, where it was played by the L.S.O. under Arthur Nikisch. (This was the same day as the premiere of Elgar’s Falstaff, but the older composer did not hear Butterworth’s work, since he had gone with family and friends to visit Fountains Abbey!) The work was most favourably received by the audience and by the critics. Henry Hadow referred to the “new voice that had come into English music”, Cyril Rootham to the work’s “remarkable qualities and first-rate workmanship” and Edward Dent expounded that he had “no doubt that George was the only younger [English composer] who could be placed alongside [Vaughan Williams].

Other conductors and orchestras soon included the Rhapsody in their repertoire. London first heard it on 20 March 1914, at the Queen’s Hall, Geoffrey Toye conducting the Queen’s Hall Orchestra in one of Bevis Ellis’ concerts of “Modern Orchestral Music”. This concert also included the London premiere of The Banks of Green Willow, three weeks after its first performance in Cheshire.

The Rhapsody remains, after nearly 100 years, one of the best-loved British orchestral works of the early 20th century. Its influence on other English composers has been mentioned, especially Ralph Vaughan Williams (Pastoral Symphony), Gerald Finzi (Severn Rhapsody), Ernest Moeran (First Rhapsody) and some of the early instrumental works of Herbert Howells, all these dating from the early 1920s. It is also interesting to note that four bars of the Rhapsody are quoted in a neglected work by Harold Truscott (Elegy for Strings), which dates from 1943.

The Banks of Green Willow

Butterworth’s last complete orchestral work dates from 1913, and is scored for a smaller orchestra than the Rhapsody, requiring only double woodwind and horns, trumpet, harp and strings; slightly fewer instruments, in fact, than the Two English Idylls. As a third folksong idyll, The Banks of Green Willow has several points of contact with the earlier works: the length (it is shorter than the Rhapsody), the imaginative use of folksong material, the arch-shaped structure, and the approximate size of orchestra. Coming two or three years after the earlier idylls, it generally shows a more mature command of orchestration and compositional technique, and a richer sense of harmony, all adding up to a work of contemplative beauty.

The composer described this work as a “musical illustration to the folk-ballad of the same name”. In addition to this traditional tune he uses another folksong – Green Bushes – as well as one original theme. The two folksongs he collected in Sussex during the summer of 1907. A solo clarinet sets a pastoral scene with the title theme, development follows in the strings and flute and oboe begin to take a more active part. The mood changes with a 3/2 Maestoso section of original music (C) in which horns are prominent, and this leads directly to brief animated string writing (D); this motif is developed into the central climax of the work, in which two bars from the opening theme are predominant. The music quickly quietens to introduce Green Bushes, first on a solo oboe (F), then on a flute, accompanied by harp arpeggios, representing the epitome of English pastoral music (G). A slower passage, for strings alone (H) is followed in the closing bars by oboe and horn, recalling the animated section but now in a much calmer atmosphere.

The premiere of The Banks of Green Willow took place on 27 February 1914, when Adrian Boult conducted a combined orchestra of forty members of the Halle and Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestras in West Kirby, a town on the Wirral peninsula where Boult’s parents were then living. This was, in fact, the young conductor’s first concert with a professional orchestra (he also gave the British premiere of Hugo Wolf’s Italian Serenade at the same concert: a considerable achievement for a debut concert!). The London premiere took place three weeks later, and seems to have been the last occasion Butterworth heard his own music.

Four arrangements of The Banks of Green Willow are known: for brass band (1973) by Phillip Brookes (unpublished), for clarinet and piano by Robin de Smet (Fentone 1987), for piano by John Mitchell (Thames 1993), and for “recorder orchestra” by Denis Bloodworth (unpublished?).

Butterworth and A.E.Housman

Butterworth’s finest songs are to be found in his two song-cycles to poems from Housman’s A Shropshire Lad: the Six Songs and Bredon Hill and Other Songs.The poet’s simple and direct verses greatly appealed to many composers, and not only from this country; in fact, some American composers showed interest before their English colleagues did, one of them writing to the poet for permission to set some of the poems, and offering a fee. Permission was given, a fee refused! The first published musical settings in England (by Arthur Somervell) appeared in 1904, eight years after the poems were published. A Shropshire Lad was Housman’s first book of poems to be published. He created the central character, Terence Hearsay, a young man from Shropshire, who would come to London and, like Housman himself, live there in exile. The collection comprises 63 brief poems in which the young lad is represented as soldier, farmer, criminal and lover. These verses of nostalgic restraint soon gave inspiration to countless composers and continue to do so, even in the 21st century!

In discussing the numerous settings of Housman’s poems, most writers have agreed that few composers have ever matched the simplicity and directness of Butterworth’s songs, although strong claims have been made for the highly individual songs of Ivor Gurney and C.W.Orr. Butterworth’s simple, delicate settings fully express the nostalgia and sentiment found in Housman’s verses, and it is this perfect match of poem and music which has appealed to singers and listeners alike. Butterworth set eleven of Housman’s poems, originally to be grouped in one narrative cycle, but later regrouped into two sets for publication.

Eleven Songs from A Shropshire Lad

1. Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad

This set first made Butterworth’s name famous and has since been regarded as a classic amongst 20th century English song-cycles. The cycle was completed in 1911, and the first known performance took place on 16 May that year, at a meeting of the Oxford University Musical Club, organised by Adrian Boult; the performers were the baritone J.Campbell McInnes, with the composer at the piano. The lads in their hundreds was not performed, although four songs from the later Bredon Hill cycle were included in the programme, the omission being On the idle hill of summer. The London premiere of Six Songs took place on 20 June1911 at the Aeolian Hall, McInnes this time being accompanied by Hamilton Harty. The work was well received by the audience who demanded an encore of The lads in their hundreds, then presumably receiving its first performance. The songs were dedicated to V.A.BARK.’, that is, Victor Annesley Barrington-Kennett, a contemporary of Butterworth’s at Eton and Oxford, and whose family lived in the Chelsea home which the Butterworths purchased in 1910. He, too, was killed on active service in France in 1916.

In the early 1960s, the Six Songs were orchestrated by Lance Baker, son of Ruth Gipps, the composer and conductor. In his work as a whole Baker has been careful to retain something of the style of the orchestral Rhapsody. The current volume includes a new arrangement for orchestra of all eleven Housman songs, by Phillip Brookes, for slightly smaller forces than Baker’s, but very successfully maintaining the delicate nature of much of Butterworth’s writing.

Loveliest of trees

This Housman poem has probably been set more times than any other, and in 1976 at least 35 settings were known. Butterworth’s setting is one of his finest and best-known, its thematic material forming the basis of the orchestral Rhapsody. The poem tells of a young man of twenty admiring the cherry tree in bloom, while simultaneously regretting the rapid passing of life, even with fifty more years in which to renew his admiration. The fine melodic contour of the introduction, perhaps suggesting the falling cherry blossom, sets a calm, pastoral atmosphere and leads into the poignant vocal line which forms the basis of the Rhapsody. In verse one Butterworth uses what is for him the unusually wide range of a minor tenth. The second verse (bar 22), in which the young man reflects on the passing of the years, contains a very sparse accompaniment, while flowing arpeggios underline the vocal part of the final stanza (bar32), suggesting progressions from Debussy’s Arabesque No.1 for piano (1888), also in E major. The epilogue (bar 43) develops the main theme in thirds, a characteristic Butterworth touch.

When I was one-and-twenty

In this simple song Butterworth took a traditional tune in the Dorian mode, the identity of which remains a mystery, although claims have been made to suggest a traditional tune called Through Moorfields. His setting of the story of the unheeding young man falling in love but despairing a year later, is a sensitive treatment of the words, the repetition of “’tis true” at the conclusion creating the appropriate hint of sadness. C.W.Orr, whose Housman settings are also renowned, was not a great admirer of Butterworth’s songs, and castigated this song for its “atrociously feeble folktune”.

Look not in my eyes

This song follows on in similar vein, although with specific reference to the Narcissus legend, that is, one of self-worship. Its folk-like character is apparent throughout, with the inevitable flattened sevenths, while the almost perpetual 5/4 time avoids making it yet another four square folk-tune.

The first three songs can be grouped together as being lyrical and full of simple charm. The next three songs have a more dramatic nature.

Think no more, lad

The original manuscript gives some indication of how far Butterworth made alterations before the final published form was achieved. The second and third verses underwent drastic changes, and the overall tonality was altered from G minor to G sharp minor. The reckless mood of the poem is well captured in the music, and the offbeat chords (verse 2, bar 151) and rapid arpeggios (verse 3, bar 170) make the accompaniment more complex than it is elsewhere in the cycle.Butterworth repeats the first verse after the second, with an identical vocal line until the climactic “falling sky” (bar 180), matched by a more virtuosic accompaniment with a relatively rare use of word painting for the composer. It is an impressive ending.

The lads in their hundreds

The message here is simple: young men attend the annual Ludlow fair, perhaps for the last time – a good example of the irony in the relationship between Butterworth’s life and the poems he chose to set. The lilting vocal line, almost inevitably in a continuously compound time, fits the words perfectly. Again, the composer changed the tonality of the song, the original key being F major, not F sharp major.

Is my team ploughing?

This remarkable song is the gem, not only of the cycle, but also of all Butterworth’s songs. Coming after what are essentially fine, straightforward vocal settings, this particular song immediately makes its mark by its sheer simplicity and extremely moving quality. The dialogue between between the dead man and his living friend is most aptly portrayed. Housman’s eight verses alternate between these two ‘characters’, and Butterworth is content to treat each verse strophically, apart from the conclusion of the song. The dead man’s questioning verses are set simply, always pp and supported by long, descending secondary chords, apparently taken from Grieg’s String Quartet. A complete change marks the replies of the living friend, a lower vocal line, quicker and louder than before, and an accompaniment of long common chords. The masterstroke is found at the very end: “I cheer a dead man’s sweetheart; Never ask me whose” (bar 272), the words belonging to the friend, while the music of the last phrase, now soft and slow, is that of the dead man, a fact accentuated by the use of secondary chords. The effect of the dead man’s question remaining unanswered is heightened by the unresolved minor added-sixth chord at the end, although Ernest Newman surprisingly thought “that Butterworth has failed … to find the right musical equivalent for the poignant end of the poem”. He ironically described this song as “ a sort of long-distance telephone call” between the two men.

2. Bredon Hill and Other Songs

This cycle was published in 1912, a year after the Six Songs, and seems to have been an immediate success, contemporary writers being full of praise for these charming and original songs with their wealth of melodic and harmonic beauty. The accompaniments are generally more complex, notable in On the idle hill of summer, the finest of the set.

Bredon Hill

This well-known poem has been set by a number of composers, among them Peel, Somervell and Vaughan Williams, and writers have invariably compared them. The constant reference to bells invites musical imagery, but Butterworth has been careful not to make his bells too assertive. A poem of this length, with its seven stanzas, requires variety of musical content (Peel’s popular setting is essentially strophic), and Butterworth has taken advantage of its dramatic possibilities. The poem briefly describes love, hope and sadness, with constant reference to bells in various circumstances: Sunday, wedding, funeral. This is one of the composer’s most elaborate settings, and much use is made of recurring ideas, for example, the minute introductory figure and the flowing quaver accompaniment. Variety is achieved by generally avoiding a strophic setting and by making use of ascending semitonal key shifts. The final stanza, now back in F major, contains the climax of the song at “O noisy bells, be dumb; I hear you, I will come”. Here, Butterworth uses interesting harmonies, a sudden minor tonality and effective use of the whole-tone scale.

Oh fair enough are sky and plain

This song appears as the first in the autograph score, and so could well date from 1909. Another ‘Narcissus’song, it poses few problems. The accompaniment is sparse, largely comprising isolated (or pairs of) chords, except in the second verse, where the voice is subservient to the rippling accompaniment of the ‘pools and rivers’ (bar 416).

When the lad for longing sighs

The folk-like element and gentle lyricism recall Look not in my eyes, and the three short verses produce a song of delicate simplicity. Melody and harmony are straightforward throughout.

On the idle hill of summer

That this song does not appear in the original manuscript of Butterworth’s Housman settings could suggest a slightly later date of composition. It is yet another example of the irony in the relationship between the composer’s life and the choice of poems he set. The poet hears soldiers marching in the distance while he idly dreams on a hill. After meditating on the folly of war, he decides to go himself. Although the accompaniment is the most complex in any Butterworth song, there are times when it remains static, with repeated throbbing syncopated added-sixth chords, representing ‘the steady drummer drumming like a noise in dreams’, and the chords themselves somehow capturing the atmosphere of a warm summer’s day. The vocal line in the first and third verses is mostly constructed from notes of the added-sixth chord of A major, but the introduction to the second verse (bar 487) immediately ushers in a new idea, using dominant ninths and thirteenths. The fourth and final verse (bar 515) is considerably more lively, with a busy accompaniment portraying ‘Bugles’ and ‘the screaming fife’, leading to the dramatic outburst: ‘Woman bore me, I will rise’ (bar 521).

Some settings of this poem (Somervell’s, for instance) allow the piano to end boldly, but Butterworth makes his accompaniment gradually subside to pp morendo in the coda, bringing back the opening drum rhythm. One can visualise soldiers and drummer gradually retreating. This is an imaginative ending to a dramatic and very fine song, one of the composer’s most assured achievements. Its musical language, far removed from the folksong idiom, is very much in the late-Romantic tradition.

With rue my heart is laden

The simple, elegiac sentiments of the poem most aptly sum up the composer’s life. The folk-like melody is supported throughout by unobtrusive harmonies, and the opening phrase is imaginatively quoted at the end of the Rhapsody. Words, melody and accompaniment fit each other perfectly, and the song as a whole makes a worthy conclusion to the cycle.

Michael Barlow , Tandridge, Surrey, July 2006

Further reading: Whom the Gods Love, the Life and Music of George Butterworth,

by Michael Barlow (Toccata Press, London, 1997)

?Notes on the order of songs and the arrangement for orchestra

Between 1909 and 1911, George Butterworth (1885-1916) set to music eleven of the 63 poems in Alfred Edward Housman’s ‘A Shropshire Lad’. It is possible that one of them – On the Idle Hill of Summer – was completed some time after the rest, since it is not among the ten songs the composer presented in manuscript form to Eton College in 1912.

Butterworth’s intention was to group the songs in one cycle, but he changed his mind and published them in two sets, Six Songs from ‘A Shropshire Lad’ first, followed by Bredon Hill and Other Songs. All eleven songs – that is, both published sets – are included in this orchestral version, in the order in which they were published.

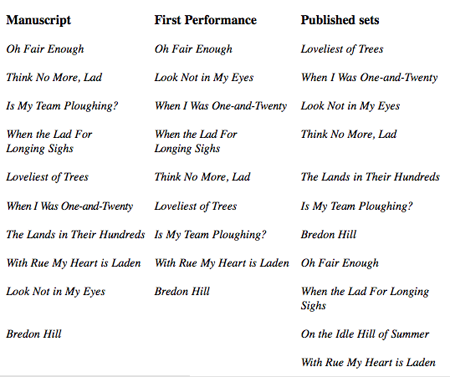

The order of these songs was not clear from the start. Below is a table of the sequence of the ten songs in the Eton manuscript; the order of performance at the première on 16 May 1911 (of only nine of the songs); and the order within the two published sets.

?This is by no means to suggest that performers should blithely ignore the published order (after all, it presumably represents Butterworth’s last thoughts on the matter); it is merely to underline that there are few certainties in music, and George Butterworth was a composer not shy of changing his mind. His sadly early death (almost foreseen in more than one of these songs) exposed rather more uncertainties than we might wish, and had he survived the carnage of the Great War we might have learned more of his own thoughts about the relationship between these songs.

Notes on orchestrating an English classic

There is no suggestion that George Butterworth ever contemplated arranging any of his ‘Shropshire Lad’ settings for voice and orchestra. This unassailable fact resulted in a degree of genuine discomfiture when I began to orchestrate the ‘Shropshire Lad’ songs; for, whatever the result, I could hardly say that I had completed something that the composer had desired.

But – and almost uniquely – aspects of these songs are already deeply associated in our collective psyche with orchestral colours, because of the composer’s own Rhapsody: ‘A Shropshire Lad’. It is also true that in several songs, including When I was One-and-Twenty, The Lads in Their Hundreds, Is My Team Ploughing? and When The Lad for Longing Sighs, Butterworth adopts a spare, almost neutral style of accompaniment that lends itself towards orchestral transcription more readily that an overtly pianistic style might do.

There are also some precedents. Butterworth orchestrated his song cycle Love Blows as the Wind Blows, which was originally for chamber forces (see Butterworth: Volume II in this series). Similarly, his close friend Vaughan Williams had already orchestrated three of his Songs of Travel and would later orchestrate his own Housman settings, On Wenlock Edge (which date from 1909, making them early contemporaries of Butterworth’s settings); they were originally for voice, piano and string quartet.

Size of the orchestra and choice of instruments

Butterworth’s Rhapsody is for a large band (even though the composer rarely uses it at full power). I took the view that to use such an orchestra for these songs might cause soloists and conductors more headaches that they need in trying to find a proper balance between voice and orchestra. In any event, it would increase the cost of performance, and I wanted to make this cycle available to amateur ensembles as well as professional.

Consequently, I have scored these songs for small orchestra. This is what Butterworth himself did when he orchestrated Love Blows, and I have based this orchestra on that one, with the addition of one trumpet, timpani and a triangle. I have also used a harp, which is (just) optional. (I did consider not using a harp at all, a course which could have been successful for most of the songs, but decided that the benefits one would bring to O Fair Enough outweighed any other considerations.)

For percussion, I used only what the composer had used in the Two English Idylls: timpani and triangle.

As far as any embellishment of the accompaniment went, it was obvious that the existing piano part would be altered in the process of orchestration; chords would need to be laid out differently, figurations changed to accommodate the techniques of orchestral instruments. However, there would likely be opportunities to go beyond the limits of a pianist’s two hands and bring subtleties of emphasis that were not apparent in the original.

When such an opportunity arose I would ask myself, “Could Butterworth have written what I want to do without altering the accompaniment significantly?” If the answer was yes, I would usually avoid the embellishment, if no if might include it. In other words, the fact that Butterworth could have easily done what I wanted, but chose not to, became an implied prohibition on my doing it at all. The emphasis, though, is on ‘easily’, since there are many places where embellishments could have been included only at the expense of other important figurations.

There are not many examples, but the birdsong in the flute around figure 20 (“…and hear the larks so high about us in the sky”) is one where it seemed to me that the composer could not have included such a passage without losing the impetus of the accompanying arpeggio figuration. Consequently, I felt justified in including it in the orchestral version on the basis that there was no clear implied prohibition.

None of this – of course – justifies my orchestrating these songs. I simply hope that the results bring pleasure and perhaps cast a different light on the songs, so that we may hear to them afresh.

Phillip Brookes, Market Drayton, 2006

English Idylls, Rhapsody, Banks of Green Willow: Conductors’ scores and parts available from Chester Novello (www.chesternovello.com). Eleven Songs: Conductors’ scores and parts available to order from Musikproduktion Hoeflich, München (www.musikmph.de). Reprints from copies of the collection Phillip Brookes, Market Drayton.

|