Max Christian Friedrich Bruch

(b. Cologne, Rheinprovinz, Königreich Preußen, 6. January 1838 – d. Friedenau, 20. October 1920)

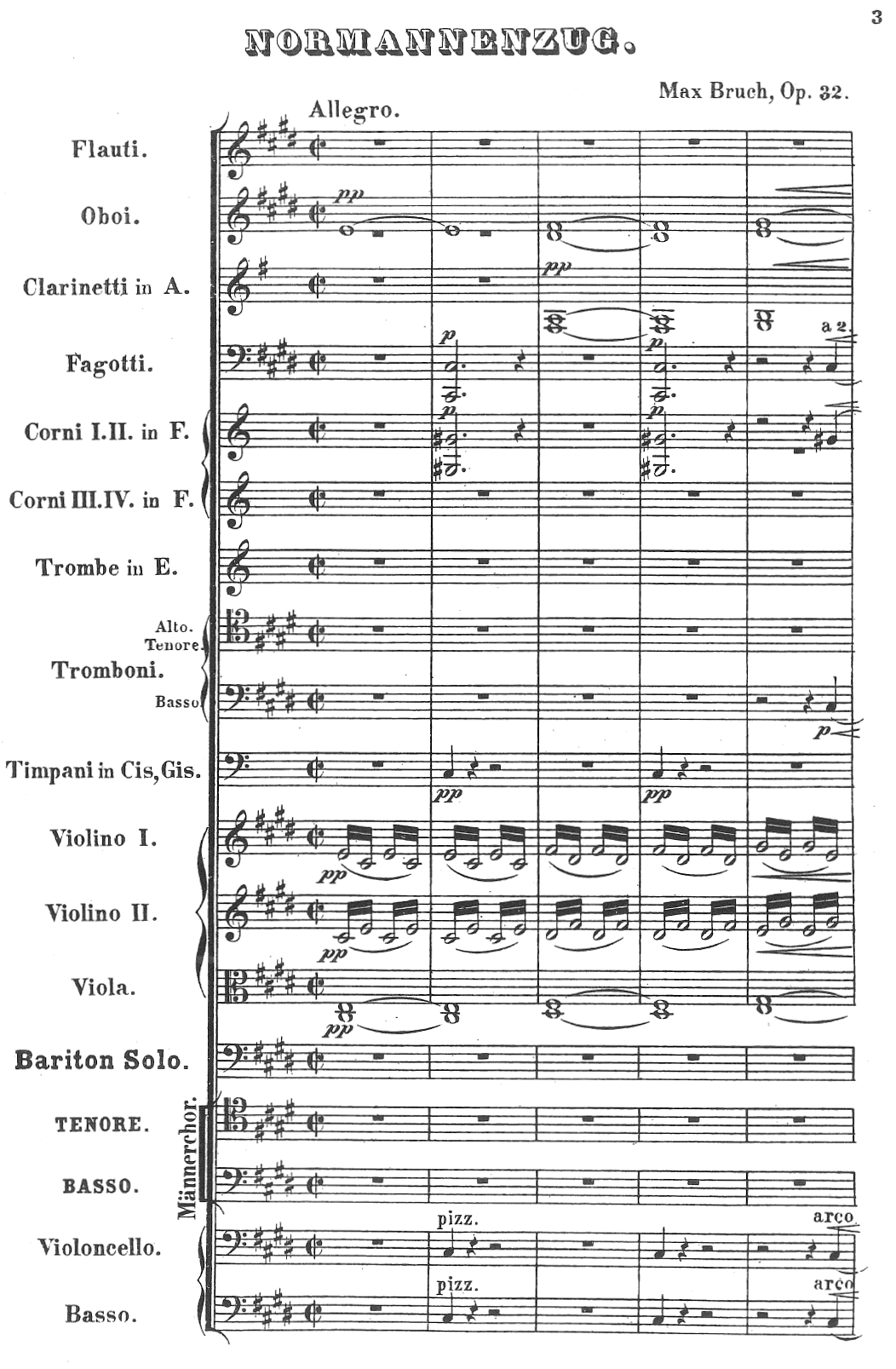

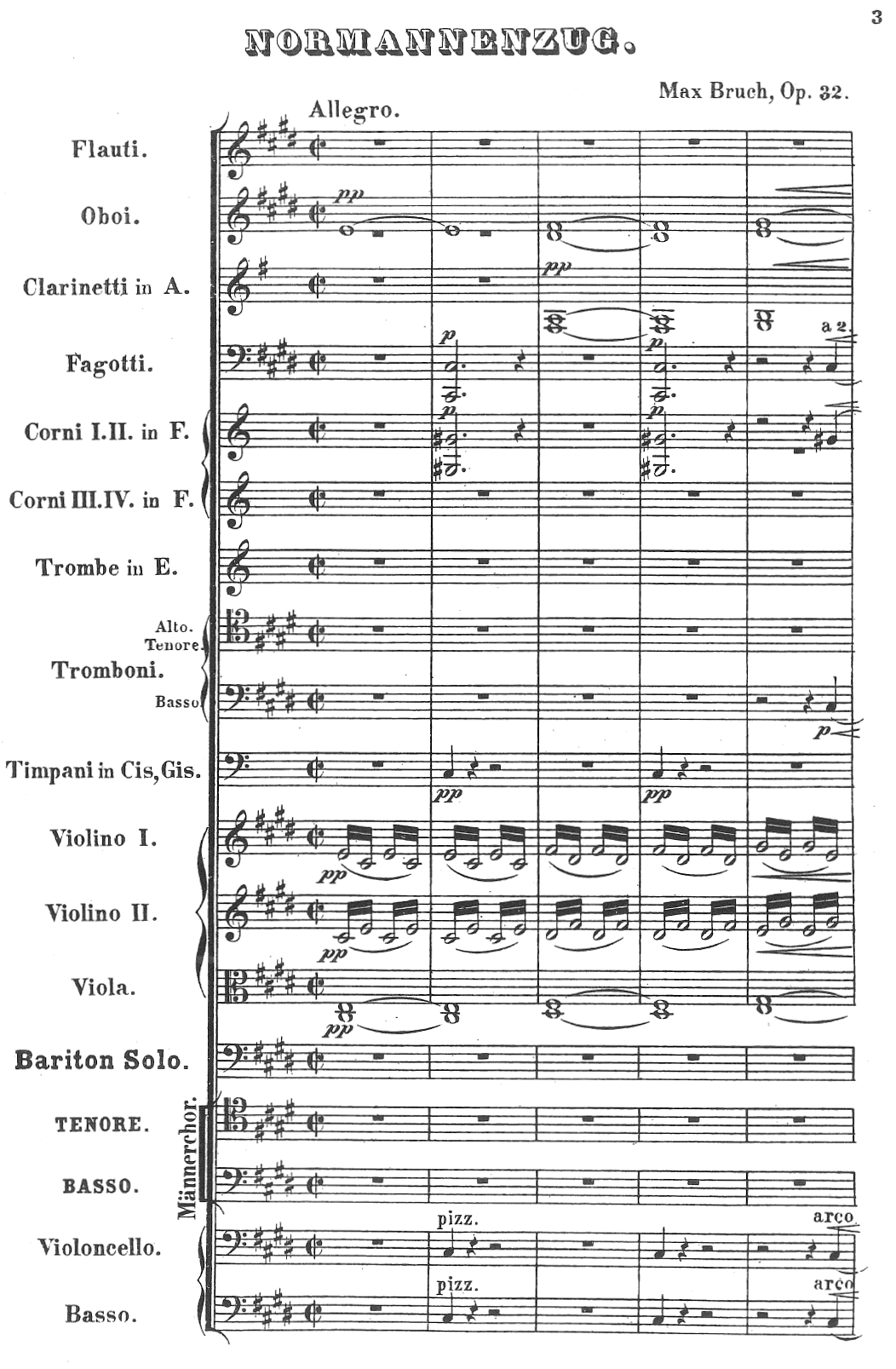

The Lay of the Norsemen

for baritone solo, men’s chorus, and orchestra, op. 32

(Normannenzug für Bariton-Solo, unison Männerchor und Orchester, op. 32 )

First Performance: 1870, Leipzig

Max Bruch was a German composer who wrote over 200 works, notably his moving Kol nidrei for cello and orchestra, op. 47, and the first of his three violin concertos (Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 26) (1866), which has become a staple of the violin repertory. Although he was raised Rhenish-Catholic, the National Socialist party banned his music from 1933-1945 due to his name, his well-known setting of a melody from the Jewish Yom Kippur service, and his unpublished Drei Hebräische Gesange for mixed chorus and orchestra (1888).

Bruch was also an accomplished teacher of music composition from 1892-1911, conducting seminars and ensembles at the Royal Academy of Arts at Berlin (Königliche Akademie der Künste zu Berlin). British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams studied with Bruch, describing him as a proud and sensitive man. Bruch actively resisted the Lisztian/Wagnerian musical trends of time, and modeled his works on those of Mendelssohn and Schumann. His concerti share structural characteristics with Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor (omitting the first movement exposition and linking multiple movements). His most lasting contributions to chamber music include works written for his son Max, who was a clarinetist.

Child of his time

Bruch was born in the same decade as Johannes Brahms, Georges Bizet, and four of the Russian Five or “Mighty Handful” (Могучая кучка). At the age of fourteen (1852), he was awarded the Mozart Prize of the Frankfurt-based Mozart Stiftung, which enabled him to study with virtuoso Ferdinand Hiller. In 1858, he moved on to Leipzig and then held posts in Mannheim (1862-1864), Koblenz (1865-1867), and Sondershausen (1867-1870).

Beginning in his early twenties, he received commissions for chorus, orchestra, and soprano solo such as Jubilate Amen, op. 3 (1858) and Die Birken und die Erlen, op. 8 (songs of the forest for men’s and women’s choruses with soloists, 1859). Even at this early period, Bruch showed a preference for ancient literary material. Works like Frithjof: Szenen aus der Frithjof-Sage, op. 23 (1864), an oratorio based on a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga which the Swedish poet Esaias Tegner had reworked as an epic poem in 1820, were well-received by audiences. After its premiere in Vienna, one reviewer observed, “Its success can be measured by the deafening applause after each scene, and the recall of the composer three times at the end.” Bruch’s mother praised his harmonies in this period as “straightforward and splendid.” Verbal reports from eyewitnesses and the soloist confirmed that even the orchestra enjoyed the work, featuring a combination Bruch used again in several choral works, ncluding his Normannenzug (hearty male chorus, melodic solos, and an un-Wagnerian view of Valhalla.

Choral Works

During the next decade, Bruch went on to compose dozens more such works that were snapped up by amateur and professional choruses. They ranged eclectically across time and nationality for their content, but still emphasized early texts. Examples include Schön Ellen, op. 24 (a ballad by Geibel for Bremen, 1867) and Salamis: Siegesgesang der Griechen, op. 25 (a work for male chorus and soloists by H. Lingg, Breslau, 1868).

The highpoint of this period coincided with Bruch accepting a position in Berlin in 1870. Here, he wrote the two women’s cantatas of op. 31 (1870, Die Flucht nach Egypten and Morgenstunde); Normannenzug, op. 32 (setting a balled by J. V. von Scheffel, unison male voices and baritone soloist, 1870); three mass movements, op. 35 (Kyrie, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, 1870) for two soprano soloists and mixed chorus with orchestra; the full-length oratorio Das Lied von der Glocke, op. 45 (after Schiller, 1872), and his greatest success in Berlin, Odysseus: Szenen aus der Odyssee, op. 41 (written for soloists and mixed chorus to a text by W. P. Graff, 1872).

He held several prestigious positions, directing the Liverpool Philharmonic (1880-1883) and leading notable concerts in Berlin and northern German cities. He went on an American tour, directed singing societies, and continued to compose for men’s chorus (Kriegsgesang, op. 63 and Leonidas, op. 66, 1894-1896) and for mixed chorus (over twenty more works in German dating from the 1870s through his last choral work in 1919 (Trauerfeier für Mignon, op. 93 (after Goethe).

The key to understanding the enigma of Bruch’s oeuvre lies in our knowledge of German life in the late Romantic period, a time when Romantic and Classical heroes were held up as metaphors for contemporary successes. English oratorios of the eighteenth-century had preferred Old Testament models to symbolize the strivings and successes of the British populace, but the German Romantics turned to their own contemporary poetry, based in Germanic legends and medieval tales.

Normannenzug, op.32

This twelve-minute work in C-sharp minor for baritone solo, unison male chorus, and orchestra was published just after its 1870 premiere in Leipzig. Breitkopf und Härtel issued both full and short scores for the cantata, which calls for double winds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings.

The musical texture for the first half of the cantata is responsorial, with the baritone soloist introducing each four-line stanza of text, echoed completely or in part (often just the final couplet) by the male chorus. The soloist drops out at the text “Und wir ziehen stumm/And we fall silent” and leaves the chorus to mourn quietly as a “ein geschlagen Heer/a defeated army.” The climax of the piece brings the orchestra, soloist and chorus together in a rousing series of “Steig auf!/Rise up!” and then the textures reverse, with the chorus fading away in the last stanza to leave the baritone dreaming away the winter night.

The original German text is excerpted from the ninth chapter (entitled “Die Waldfrau”) of Joseph Victor von Scheffel’s (1826-1886) historical romance Ekkehard: A Tale of the Tenth Century (1857). This novel is based on the life of Ekkehard I (d. 973), Dean of the Abbey of St. Gall (Fürstabtei St. Gallen). As a member of the Benedictine order, Ekkehard was of noble birth, made a pilgrimage to Rome to receive relics of St. John the Baptist from Pope John XII, and was distinguished as a poet (his Latin epic Waltharius and ecclesiastical hymns and sequences were well-known in the medieval period). Robert White provided an English adaptation for twentieth-century reprints of the work.

By the ninth chapter of Ekkehard, the title character is journeying through the forests of Schwabia in late November. He decides to seek out the elderly Woman of the Wood after a discussion of witchcraft. She recalls Friduhelm, a sweetheart of her youth, who was kidnapped and became a Scandinavian pirate. She hums “an old Norseman’s song which he had once taught her,” (“Die traurige Jahreszeit gemahnte sie an ein altes Nordmännerlied, das er sie einst gelehrt; das summte sie jetzt vor sich hin:”) printed in rhyming verse.

Nordmännerlied

Der Abend kommt und die Herbstluft weht,

Reifkälte spinnt um die Tannen,

O Kreuz und Buch und Mönchsgebet –

Wir müssen alle von dannen.

Die Heimat wird dämmernd und dunkel und alt,

Trüb rinnen die heiligen Quellen;

Du götterumschwebter, du grünender Wald,

Schon blitzt die Axt, dich zu fällen!

Und wir ziehen stumm, ein geschlagen Heer,

Erloschen sind unsere Sterne,

O Island, eisiger Fels im Meer,

Steig’ auf aus nächtiger Ferne!

Steig’ auf und empfah unser reisig Geschlecht,

Auf geschnäbelten Schiffen kommen

Die alten Götter, das alte Recht,

Die alten Normannen geschwommen.

Wo der Feuerberg loht, Glutasche fällt,

Sturmwogen die Ufer umschäumen:

Auf dir, du trotziges Ende der Welt,

Die Winternacht woll’n wir verträumen!

Song (or Lay) of the Norsemen

Evening comes and the autumn breeze blows,

Cold frost spins around the fir trees,

O Cross and Book and monk’s prayer –

We must all depart.

Our house grows dim and dark and old,

The holy wellsprings therein are bleak;

You who are watched over by the gods, you green forest,

The axe is already flashing to fell you!

And we fall silent, a defeated army,

Our stars are extinguished,

O Iceland, icy rock in the sea,

Rise up on the horizon!

Rise up and receive our race,

On sharp-beaked ships come

The old gods, the old law,

The old Norsemen returning.

Where Hecla glows, glowing ash falls,

Storm waves foam the shores:

On you, O desolate end of the world,

We will dream away the winter’s night!

Influence of Schumann

Twenty years after Robert Schumann’s Waldszenen, Max Bruch assimilated Schumann’s message in “Vogel als Prophet” in his cantata Normannenzug from 1869. Bruch quotes precisely this motive while the choir sings “Du Götterumschwebter, du grüner Wald/You who are watched over by the gods, you green forest,” an allusion to Schumann’s Waldszenen. The parallel sixths are present, this time with a dominant pedal, and as in Schumann the motive repeats immediately. Moreover, Bruch is not simply presenting his motive emblematically to refer to forests. Although he would not have known the quotation of Eichendorff present in Schumann’s initial draft, he evidently knew Schumann’s Faust setting, because his poetic text strongly assimilates the sense of impending danger. His “grüner Wald” is no idyllic forest; on the contrary, the trees, and the homeland that they represent, are imperiled: “Schon blitzt die Axt, dich zu fällen!/The axe is already flashing to fell you!”

While Romantic composers certainly valued a motive for its intrinsic beauty, this quality of a motive was also a factor of the depth of its poetic meaning. The more layers of textual significance, both private and public, the greater the musical-poetic value. This is what Schumann meant in his defense of Berlioz’s programmatic approach to composition: “The greater the number of elements cognate in music, which the thought or picture created in tones contains, the more poetic and plastic the expression of the composition.” (p. 181, On Music)

In Waldszenen, Schumann quoted himself, alluding to Goethe’s Faust and to Mendelssohn. With his own citation, Bruch endorsed Schumann’s imagery. In so doing, he proved his own ability to decode Schumann’s poetic meaning.

Publications and resources

Christopher Fifield’s Max Bruch: His Life and Works (Boydell, 1988, reissued 2005) is the only full-length documentary biography of Bruch; it includes a musical analysis in English of all of his published works, including three German operas and several oratorios. This is the best source for a discussion of Bruch’s letters and other contemporary sources that support his place in the vibrant musical culture of his time.

Later editions include a piano-vocal score in Breitkopf & Härtel’s V. A. edition series (V. A. plate 3277) and its recent reprint by Recital Publications (Huntsville, TX, 1998). Performance material is available for hire from Breitkopf & Härtel, and through G. Schirmer in the United States and Canada.

©2013 Laura Stanfield Prichard, University of Massachusetts and San Francisco Symphony

Übersetzung: Klaus Schmirler