Johann Christian Bach

(geb. Leipzig, 5. September 1735 – gest. London, 1. Januar 1782)

Fünf Sinfonien

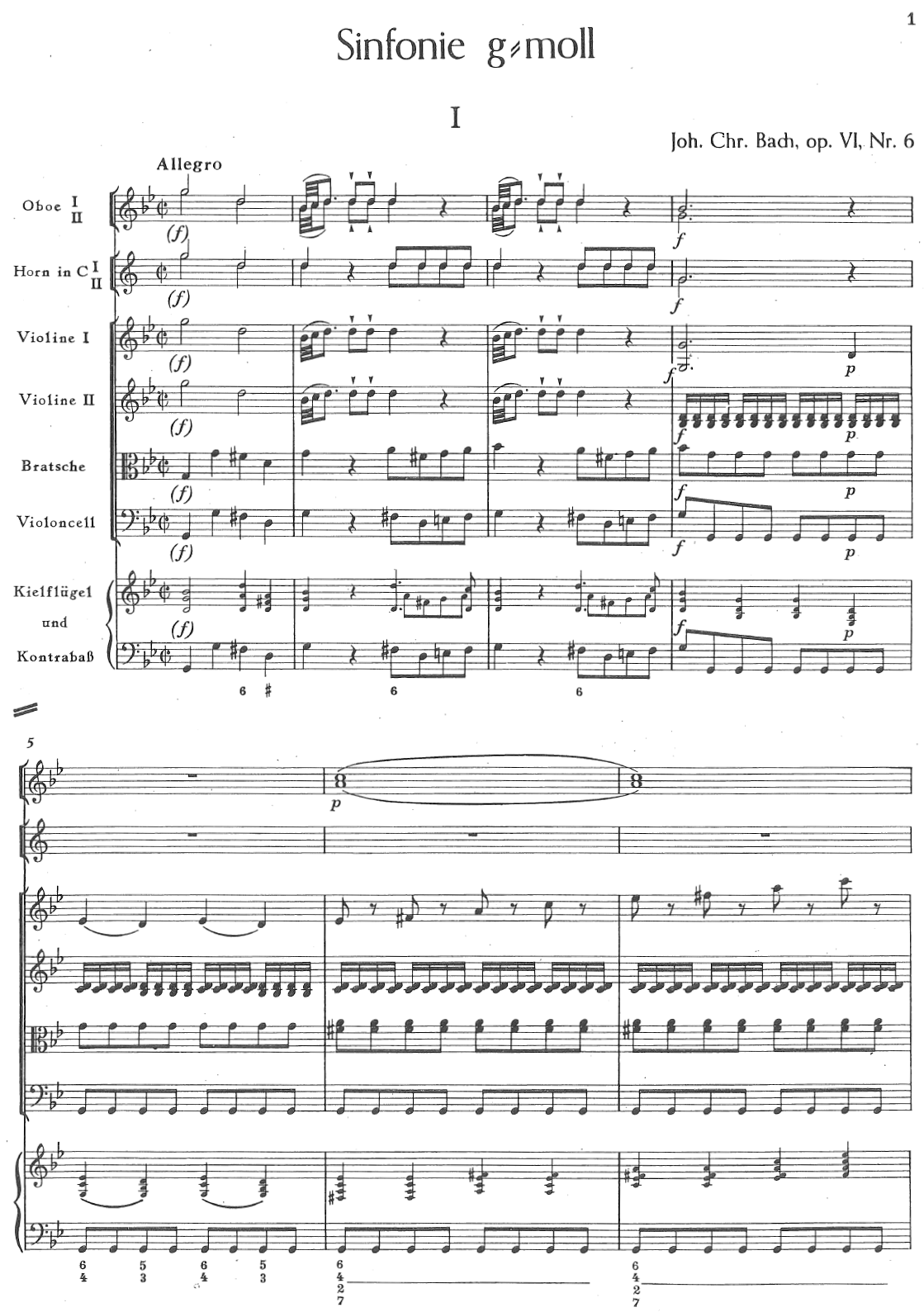

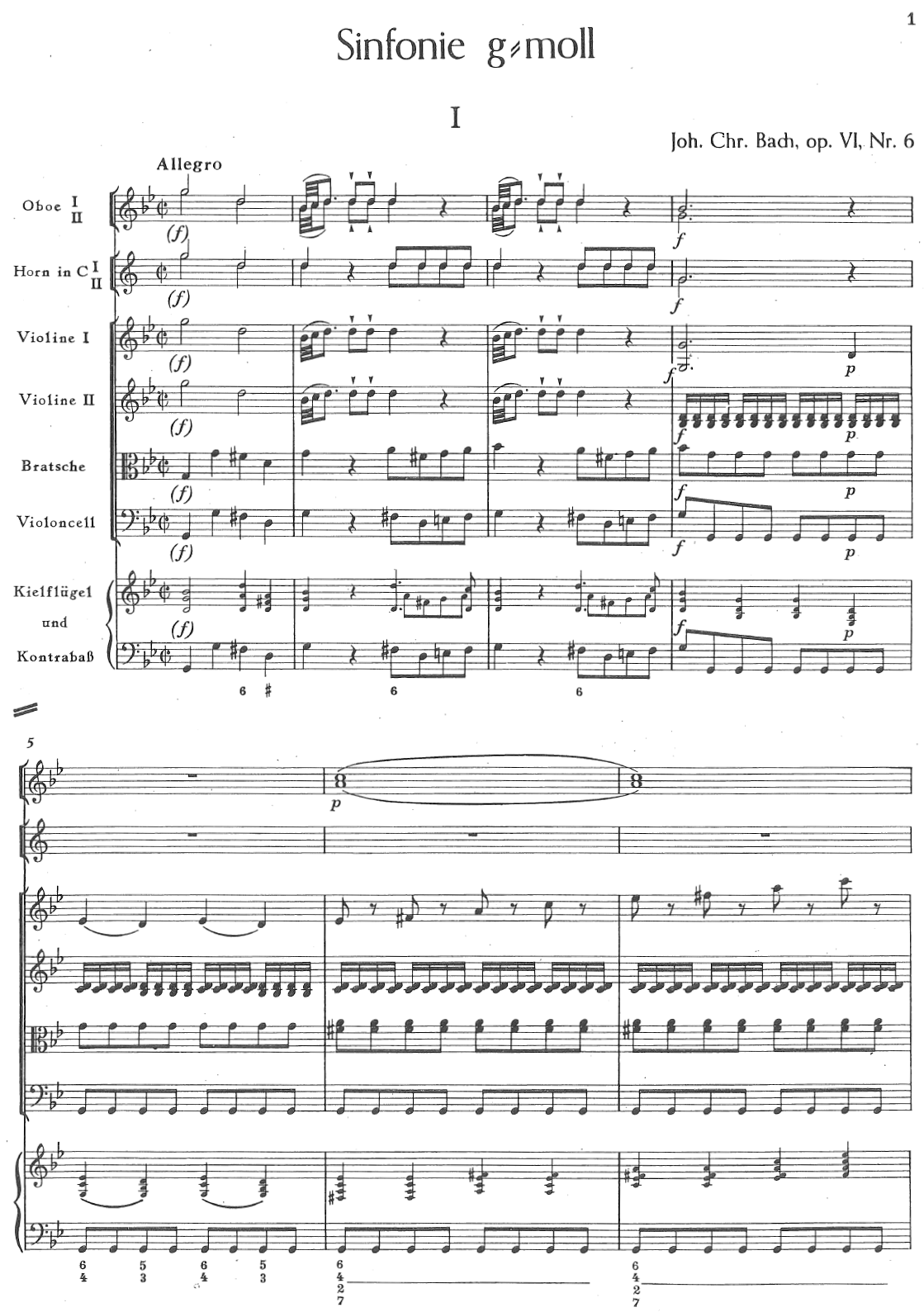

1. Sinfonie g-Moll, S. 1-30

2. Sinfonie B-Dur, S. 31-57

3. Sinfonie D-Dur, Ouverture zur Oper Temistocle, S. 59-84

4. Sinfonie E-Dur für Doppelorchester, S. 85-160

5. Sinfonie D-Dur, S. 161-194

Im Gegensatz zu seinem Vater Johann Sebastian kam Johann Christian Bach viel herum. Aufgewachsen in Leipzig, erhielt er vermutlich von seinem Vater zunächst Unterricht in Klavier und Musiktheorie. Als dieser 1750 starb, war Johann Christian 14 und zog zu seinem Bruder Carl Philipp Emmanuel nach Berlin, der ihn Komposition und Klavier lehrte. 1754 ging er nach Italien und hatte zeitweise Unterricht bei Padre Martini in Bologna. 1760 wurde Bach zweiter Organist am Mailänder Dom und konnte noch im gleichen Jahr seine erste Oper Artaserse in Turin uraufführen. Schon seine zweite Oper Catone in Utica wurde 1761 in Neapel ein großer Erfolg und in den nächsten Jahren in mehreren Städten Italiens gespielt. 1762 nahm er das Angebot an, ein Jahr am King’s Theatre in London Opern zu schreiben. Das Leben und Arbeiten dort gefiel ihm so sehr, dass er beschloß zu bleiben. 20 Jahre sollte er in London wirken, wo er 1782 starb.

1764 traf er hier den achtjährigen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, mit dem er mindestens einmal zusammen improvisierte. Bach hatte mittlerweile den deutschen Komponisten und Gambisten Karl Friedrich Abel kennengelernt, mit dem er die Bach-Abel-Konzerte ins Leben rief, eine öffentliche Konzertreihe, die von ihnen geleitet wurde. Daneben komponierte Bach als freischaffender Komponist vor allem geistliche Werke, Opern, Sinfonien, Solokonzerte, Kammermusik und Klaviersonaten. 1772 und 1775 wurden Auftragsopern für Mannheim unter seiner Anwesenheit uraufgeführt: Temistocle (siehe Nr. 3, Sinfonie D-Dur), und Lucio Silla. In den 1770er Jahren reiste er auch nach Italien und nach Paris, wo er den Auftrag für die Oper Amadis de Gaule erhielt, die 1779 uraufgeführt wurde (siehe Nr. 5, Sinfonie D-Dur). Bach erhielt daraufhin einen weiteren Auftrag für eine Oper, verstarb jedoch während der Arbeit mit nur 46 Jahren. Von den vier bedeutenden Komponistensöhnen seines Vaters war er der jüngste, starb jedoch als erster. Ihm folgten Wilhelm Friedemann (1710-1784), Carl Philipp Emmanuel (1714-1788) und Johann Christoph Friedrich (1732-1795). Von allen Komponisten der Familie Bach war Johann Christian der kosmopolitischste und damals international bekannteste.

Etwa 40 Sinfonien schrieb Johann Christian Bach, die allesamt einen bedeutenden Platz in seinem Gesamtwerk einnehmen. Die hier vorzustellenden fünf entstanden ab 1762 und sind somit in seine Londoner Zeit einzuordnen. Sie verdeutlichen repräsentativ Bachs Entwicklung der Gattung von der italienischen Theater- zur Konzertsinfonie, mit der er ihr als eigenständiger Form zum Erfolg verhalf. Die Opernouvertüren waren Unterhaltungsmusik mit orchestraler Brillanz und einer klaren Form. Ihre Dreiteilung schnell-langsam-schnell innerhalb eines Satzes entwickelte sich zu Bachs Zeit zu drei separaten Sätzen, zumeist Allegro-Andante-Allegro. Extrem langsame Vortragsbezeichnungen wie Adagio oder Grave erscheinen ebenso selten wie Molltonarten.

Stellenweise verwirrend bei Bachs Sinfonien ist, daß manche Opus-Zahlen mehrfach vergeben wurden bzw. ein Werk bei verschiedenen Verlegern unterschiedliche Opus-Zahlen erhielt. Die heutige Numerierung bezieht sich auf den Thematic Catalogue (New York 1999, = The Collected Works of Johann Christian Bach 48,1) von Ernest Warburton, der auch die 48-bändige Gesamtausgabe The Collected Works of Johann Christian Bach (New York 1984-1999) herausgab. Zur leichteren Auffindung habe ich bei jedem Werk auch die genaue Position innerhalb der einzigen Gesamtaufnahmen der Sinfonien und Opernouverturen Bachs angegeben, eingespielt von The Hanover Band unter Anthony Halstead, jeweils aufgenommen 1994-2000: Complete Symphonies (5 CDs bei cpo, veröffentlicht 2002), Complete Opera Ouvertures (3 CDs bei cpo, veröffentlicht 2003).

1. Sinfonie g-Moll, S. 1-30

Allegro – Andante più tosto Adagio – Allegro molto

komponiert: (1762-1769)

damalige Opuszahl: op. 6, Nr. 6

heutige Numerierung: C12, enthalten in Bd. 27

Complete Symphonies, CD 2: Track 16-18

Alle sechs Sinfonien aus op. 6 sind für 2 Oboen, 2 Hörner, Streicher und Basso continuo besetzt. Nr. 6 ist die einzige aller Sinfonien Bachs in einer Molltonart, die der Komponist dramatisch und leidenschaftlich gestaltet, durchaus unter „Sturm und Drang“ einzuordnen. Der erste Satz ist durch zwei kontrastierende Themen bestimmt, das erste in der Grundtonart, rhythmisch prägnant, das zweite (T. 26) in der Durparallele B-Dur, weich fließend. In einer Durchführung (T. 68) wird der zweite Teil des ersten Themas siebenmal in verschiedenen Tonarten gespielt und führt am Ende zur Grundtonart zurück. In dieser Tonart erscheint dann in der verkürzten Reprise (T. 102) das zweite Thema, bis der Satz mit dem ersten Thema endet. Dieses Formmodell weist schon Merkmale der klassischen Sonatenhauptsatzform auf.

Der zweite Satz in c-Moll lässt die Bläser nun außen vor und ist ein Streichquartett mit Basso continuo. Ebenso ungewöhnlich ist die sehr differenzierte Satzbezeichnung Andante più tosto Adagio, die einen anderen Charakter verlangt als das übliche italienische Andante im zweiten Satz, wie es sich bei den ersten fünf Sinfonien dieses Opus 6 findet. So wird beim zweiten Erscheinen des Themas (T. 9) dieses in den tiefen Streichern gespielt, während die zweite Violine chromatisch abwärts schreitet. Dieser starke Ausdruck wird in dem folgenden Abgesang (T. 19) durch Forteakzente weitergeführt. Das zweite Thema (T. 25) mündet in einem Crescendo, das am Ende plötzlich in ein Piano ausläuft, so wie auch der ganze Satz nach einem Crescendo sogar im Pianissimo verhallt.

Der dritte Satz weist keine so deutlichen Themenbildungen wie die ersten beiden Sätze auf. Ein erstes vorwärtsdrängendes Thema bietet Material, das vom zweites Thema (T. 15) in der Durparallele B-Dur aufgegriffen wird. Ohnehin ist die Konzeption der Formteile dieses Satzes am Kopfsatz der Sinfonie orientiert. So besteht auch die Durchführung (T. 38) aus mehrfach repetierten Motiven (neunmal gespielte 2-Takt-Gruppen), die sich nur harmonisch verändern, und die Reprise (T. 61) beginnt mit dem zweiten Thema in der Grundtonart. Statt der groß angelegten Crescendobögen der Mannheimer Schule bevorzugt Bach scharfe dynamische Gegensätze und Terrassendynamik, am extremsten zu beobachten im Übergang von der Exposition zur Durchführung: Fortissimo – Piano – Fortissimo. Der Schluß verhallt, ebenso wie der des zweiten Satzes, überraschend im Pianissimo.

2. Sinfonie B-Dur, S. 31-57

Allegro con spirito – Andante – Presto

komponiert 1767 oder 1768

damalige Opuszahl: op. 9, Nr. 1 bzw. op. 21, Nr. 1

heutige Numerierung: C17a, enthalten in Bd. 27

Complete Symphonies, CD 4: Track 1-3

Im Unterschied zur ersten Sinfonie dieser Ausgabe weist der Kopfsatz der B-Dur-Sinfonie eine voll entwickelte Sonatenform auf. Die Exposition besteht aus zwei Themen, das erste auf der Tonika von den hohen Streichern, das zweite auf der Dominante F-Dur von den beiden Oboen (T. 33) gespielt. Die Durchführung präsentiert das erste Thema auf der Dominante (T. 68) und anschließend das zweite auf der Grundtonart (T. 76), das fortgeführt wird. Die Reprise (T. 111) ist im Vergleich zur Exposition nur leicht gekürzt.

Der zweite Satz, der auf die beiden Hörner verzichtet, ist ein langsames Menuett, hat sanglichen Charakter und weist eine Rondoform auf: Ein dreimal wiederkehrendes Ritornell (T. 1, 33/34 und 70/71) wechselt sich zweimal mit einem Couplet ab (T. 17 und 50), gefolgt von einer Coda (T. 87). Die Coda greift auf Elemente sowohl der Ritornelle als auch der Couplets zurück. Alles ist übersichtlich angeordnet.

Das Presto ist zweigeteilt, weist aber eine komplexe Formgebung auf. Im ersten Teil erscheinen drei jeweils achttaktige Themen (T. 1, 25 und 41) sowie zwei ebenfalls jeweils achttaktige Überleitungen (T. 20 und 33) sowie eine aus dem dritten Thema erwachsende Coda (T. 49). Dieses Schema mit deutlicher Trennung der Formteile wird im zweiten Teil verändert. Er beginnt wie im ersten Teil mit dem zweimal gespielten ersten Thema, bricht jedoch nach 14 Takten ab und lässt eine im plötzlichen Forte einbrechende Durchführung folgen (T. 72), die in das dritte Thema mündet (T. 80), wiederum gefolgt von einer Durchführung. Das zweite Thema erscheint erst bei Takt 118. Nun geht es in gleichmäßigen Achttakt-Gruppen wie im ersten Teil bis zum Schluß weiter: Überleitung (T. 126) – drittes Thema (T. 134) – Coda (T. 141). Bach verwendet also eine Dreiteilung innerhalb einer Zweiteilung, wobei der mittlere Teil (T. 58-117) Durchführungscharakter hat, wodurch sich der ganze Satz als eine Art Sonatensatzform entpuppt. Vereinfacht dargestellt ergibt sich eine Exposition mit den Themen 1-3, eine Durchführung sowie eine Reprise mit den Themen 2 und 3. Alles huscht (ohne Wiederholung des zweiten Teiles) in knapp drei Minuten an einem vorbei.

3. Sinfonie D-Dur, Ouverture zur Oper Temistocle, S. 59-84

Allegro di molto – Andante – Presto

UA der Oper: 5. November 1772, Hoftheater, Mannheim

heutige Numerierung: G8, enthalten in Bd. 7

Complete Opera Ouvertures, CD 3: Track 4-6

Die Handlung der dreiaktigen Opera seria Temistocle nach einem Text von Metastasio spielt um 480 vor Christus zur Zeit der Perserkriege, die das Ziel hatten, Griechenland dem persischen Reich einzuverleiben. Namensgeber der Oper ist der griechische Feldherr Temistocle. In den Ecksätzen der Ouverture griff Bach auf die Ouverture seiner Oper Caracatto zurück, die er fünf Jahre vorher komponiert hatte. Er übernahm die Sätze jedoch nicht wörtlich, sondern erweiterte die Partitur um Trompeten und Pauken und veränderte den Schlußsatz.

Der festlich erklingende Kopfsatz in Sonatenhauptsatzform weist in der Exposition zwei gegensätzliche Themen auf: vorwärtsdrängend durch begleitende Synkopen das erste in D-Dur, Ruhe ausstrahlend im Vordersatz (T. 27) durch einen einfachen Rhythmus das zweite in A-Dur. Die Durchführung (T. 55) ist kurz und bringt ein weiteres Thema, das aus dem zweiten abgeleitet ist. In der Reprise (T. 70) erscheinen beide Themen in der Grundtonart. Klanglich abwechslungsreich instrumentiert Bach den jeweils zweimal erscheinenden Vordersatz des zweiten Thema inklusive des auf dem Rhythmus des zweiten Themas basierenden dritten Themas (die Streicher sind immer dabei):

T. 27: Oboen / T. 31: Flöten und Fagotte

T. 55: Oboen und Hörner / T. 59: Flöten

T. 100: Oboen und Fagotte / T. 104: Flöten und Hörner

Bach verwendet alle möglichen Zweiergruppierungen mit Ausnahme der beiden hohen (Flöten und Oboen) und der beiden tiefen (Fagotte und Hörner) Instrumente.

Auch der zweite Satz baut auf dem Klangreiz von Instrumenten auf. Hier sind es drei Clarinetti d’amore, auch „Liebesklarinetten“ genannt, die das birnenförmige Schallstück, den „Liebesfuß“ der Oboe d’amore aufweisen. Ihr Klang ist gedämpfter als der einer üblichen Klarinette. Bachs Temistocle ist eines der wenigen bekannten Stücke für dieses Instrument überhaupt, das um 1800 in Vergessenheit geriet. Im Mittelsatz dieser Ouverture bilden die drei Klarinetten eine Einheit, insgesamt viermal spielen sie ihr Thema ohne Begleitung anderer Instrumente (T. 12, 21, 76 und 84).

Der Schlußsatz ist ein Rondo mit vier Ritornellen (T. 1, 25, 45 und 89) und drei Couplets (T. 17, 33 und 73), die immer durch eine Viertelpause abgetrennt sind. Die Ritornelle sind als Tutti im Forte gehalten, die Couplets als Concertino im Piano. Während die Couplets trotz gleichmäßig ansteigender Länge kurz sind (8 – 12 – 16 Takte), weisen die Ritornelle unterschiedliche Längen (16 – 8 – 28 – 27 Takte) und ständig wechselnde Verhältnisse von Vorder- und Nachsatz auf: das erste beginnt mit dem Vordersatz und schließt den Nachsatz an, das zweite bringt beide gleichzeitig, das dritte beginnt mit dem Nachsatz und das vierte gleicht dem ersten samt zugefügter Coda.

4. Sinfonie E-Dur für Doppelorchester, S. 85-160

(Allegro moderato) – Andante – Tempo di Minuetto

komponiert frühestens 1772

damalige Opuszahl: op. 18, Nr. 5

heutige Numerierung: C28, enthalten in Bd. 28

Complete Symphonies, CD 5: Track 13-15

Die Sinfonie E-Dur ist für ein Doppelorchester geschrieben. Beiden gemeinsam ist ein Streichquartett, nur die Aufteilung der Bläser ist anders: Orchester I hat 2 Oboen, 1 Fagott und 2 Hörner, Orchester II nur 2 Flöten. Das zweite Thema (T. 36) bietet zum ersten keinen Kontrast: beide sind sanglich, der ganze Satz ist ein „singendes Allegro“. Zwischen die beiden Themen liegt ein langgezogenes „Mannheimer“ Crescendo vom Piano bis zum Fortissimo, in dem sich beide Orchester nach und nach ergänzen, nachdem bis dahin das zweite nachgezogen hatte. Später erscheinen auch Stellen, in denen das zweite Orchester vorlegt und das erste nachzieht (T. 67 und 85). Meistens jedoch ist das erste Orchester führend wie beim zweiten Thema (T. 36) oder dem Beginn der kontrastreichen Durchführung (T. 53). Diese fängt mit dem Nachsatz des zweiten Themas (T. 53) an. Auch in der Reprise (T. 126) wird der Vordersatz des zweiten Themas ausgelassen (T. 161). Der Wettstreit der beiden Orchester verdichtet sich in der Durchführung zu einem sogar kanonischen Spiel: einmal legt das erste Orchester vor (T. 79), einmal das zweite (T. 85). Der ganze Satz wird durch die Streicher bestimmt, während die Bläser wie in der frühen neapolitanischen Sinfonie nur harmoniefüllende Funktion haben.

Dieses Verhältnis der Instrumentengruppen kehrt sich im zweiten Satz um. Nun sind es die Bläser (ohne die Hörner des ersten Satzes), die dominieren, besonders im Wechselspiel der Oboen und Flöten, während die Streicher grundieren. Den Reiz der Klangfarbe nutzt Bach weiterhin aus, indem er die Streicher des zweiten Orchesters bis auf die letzten drei Takte con sordino spielen lässt und die des ersten immer dann pizzicato, wenn sie thematisches Material des zweiten Orchesters nur begleiten: Takt 9-15 und 63-96 zum Nachsatz des Ritornell-Themas sowie Takt 32-41 zum Couplet-Thema. Die Form des Satzes ist ein Rondo: drei Ritornells (T. 1, 34 und 62) mit zwei Couplets (T. 16 und 42) samt anschließender Coda (T. 70). Im Unterschied zur dritten Sinfonie dieser Notenausgabe sind die Ritornelle piano und die Couplets forte zu spielen.

Der Schlußsatz ist ein Menuett in E-Dur in ABA-Form mit der Molltonika e-Moll im Mittelteil (T. 83). Der A-Teil beginnt mit einem 4x erscheinenden achttaktigen Thema. Das zweite Thema (T. 33) hat einen viertaktigen Vorder- und einen achttaktigen Nachsatz, der wiederholt wird, so dass der Themenkomplex 20 Takte umfaßt. Nach einer 13-taktigen Überleitung (T. 52) erscheint wieder das erste Thema. Die Orchestrierung ändert sich parallel zu diesem klaren Formaufbau. Der Mittelteil kommt ohne Hörner aus und besteht, wie der gesamte Satz, aus einer ABA-Form: zwei nur jeweils achttaktige Außenteile in e-Moll, gespielt von den Streichern, umschließen einen Mittelteil (T. 91-110) in der Parallele G-Dur, dominiert von den Bläsern, die von Streichern begleitet werden. Die Wiederholung des A-Teiles (T. 119) erfolgt wörtlich.

5. Sinfonie D-Dur, S. 161-194

Allegro con spirito – Andante – Allegretto – Allegro

anonyme Bearbeitung von Teilen aus Bachs Oper Amadis de Gaule, UA: 14. Dezember 1779,

Académie Royal de Musique, Paris

damalige Opuszahl der Bearbeitung: op. 18, Nr. 6

heutige Numerierung der Bearbeitung: XC1, enthalten in Bd. 28; die Oper ist enthalten in Bd. 10;

ordnet man die vier Sätze der Oper zu, ergibt sich die Numerierung G39 = Ouverture 1,

G39 = Ouverture 2, G39/22 (= Gavotte), G39/41 (= Gigue)

Complete Symphonies, CD 5: Track 16-19; Complete Opera Ouvertures, CD 3: Track 10-12

Die D-Dur-Sinfonie ist die einzige viersätzige, die Bach komponiert hat. Es handelt sich um eine anonyme Bearbeitung von Teilen aus seiner letzten Oper Amadis de Gaule (1779) mit der Hauptfigur des Ritters Amadis. Bis auf den zweiten Satz weisen alle eine Rondoform auf. Der erste Satz hat drei Ritornelle (T. 1, 50 und 109) und zwei Couplets (T. 33 und 84), wobei nach den Couplets Überleitungsbereiche zugefügt sind (T. 46 und 101). Im Unterschied zur Opernouverture finden sich hier Wiederholungen (T. 62-72 = 73-82) sowie ein vereinfachter Anfang, die beide auf einen Bearbeiter hindeuten.

Auch im zweiten Satz griff ein Bearbeiter in die Struktur ein, fügte im Unterschied zum zweiten Satz in der Opernfassung am Ende neun Takte zu und vereinfachte die Instrumentierung. Der Satz hat nun eine ABA-Form mit angehängter Coda (T. 52). Die Reduktion der beiden Flöten und Oboen auf jeweils ein Instrument und die Herausnahme des Fagotts unterstützen den pastoralen, fast intimen Klang dieses Satzes, der nur im Mittelteil (T. 20) etwas bewegter ist. Dieser weist in sich wiederum eine ABA-Form auf, wobei die Streicher den A- und Flöte sowie Oboe den B-Teil gestalten.

Der dritte Satz, in der Oper als Gavotte, ist wieder anders instrumentiert, nun als Streichquartett mit Oboe und Fagott, die nur im zweiten Couplet erscheinen, wobei die Oboe ein Solo spielt, das Fagott begleitet und die Streicher wiederum dieses Bläserduo mit Motiven aus dem ersten Couplet unterstützen. Die Gesamtform weist drei Ritornelle (T. 1, 43 und 75) und zwei Couplets (T. 22 und 51) auf.

Der Schlußsatz gehörte ursprünglich als Gigue an das Ende des zweiten Opernaktes. Als Sinfoniesatz hat er wiederum eine Rondoform mit Zwischenpartien. Die beiden Couplets deuten auf eine Ausweitung der Form hin. Das erste (T. 28) besteht nicht nur aus Vorder- und Nachsatz, sondern zusätzlich aus einer Erweiterung und einer Rückleitung. Das zweite (T. 40) ist mit 8 Takten für einen ersten Teil, 11-12 Takten für einen zweiten und 6 Takten Rückleitung noch ausgedehnter. Ebenso wie im dritten Satz dieser Sinfonie erscheint ein Bläsersolo. Hier ist es als Flöte-Oboe-Fagott-Trio zu Beginn des zweiten Couplets gesetzt.

Cembalo als Generabaßinstrument?

In der vorliegenden Ausgabe hat der Bearbeiter Fritz Stein 1956 eine Continuoaussetzung beigefügt, überlässt es aber dem Dirigenten, ob er davon Gebrauch macht oder nicht. Als ›Dirigierinstrument‹ wurde das Cembalo in England bis ins späte 18. Jahrhundert hinein verwendet. In Bachs frühen Sinfonien sind die Bässe noch beziffert, jedoch ist es offen, ob dieses von ihm oder seinen Verlegern stammt. In fast allen seiner späteren Sinfonien fehlt die Bezifferung. Dieses spricht aber nicht gegen die Verwendung eines Cembalos, wie Stein erklärt, denn in Bachs unbezifferten Six favourite Ouvertures von 1770 wird das Begleitinstrument im Titel ausdrücklich verlangt, wenn es dort heißt: with a Bass for the Harpsichord and Violoncello. Die ersten beiden der hier vorliegenden Sinfonien sind beziffert, die letzten drei nicht. Jedoch finden sich hier, wie Stein weiter ausführt, »harmonisch leere Stellen, die auf eine akkordische Füllung durch ein Continuoinstrument zu rechnen scheinen, die also der Dirigent am Cembalo ausgeführt haben mag.«

Jörg Jewanski, 2013

Johann Christian Bach

(b. Leipzig, 5 September 1735 – d. London, 1 January 1782)

Five Symphonies

Symphony no. 1 in G minor, pp. 1-30

Symphony no. 2 in B-flat major, pp. 31-57

Symphony no. 3 in D major, Overture to the opera Temistocle, pp. 59-84

Symphony no. 4 in E major for double orchestra, pp. 85-160

Symphony no. 5 in D major, pp. 161-94

Unlike his father Johann Sebastian, Johann Christian Bach got around in the world. Raised in Leipzig, he presumably received his first keyboard and theory lessons from his father. When Johann Sebastian died in 1750, Johann Christian was fourteen years old and moved to Berlin to stay with his brother Carl Philipp Emmanuel, who taught him composition and keyboard playing. In 1754 he traveled to Italy, where he briefly studied with Padre Martini in Bologna. In 1760 he was appointed deputy organist at Milan Cathedral and saw the première of his first opera, Artaserse, in Turin. His second opera, Catone in Utica, enjoyed great success in Naples in 1761 and was soon given in other Italian cities. In 1762 he accepted an offer to spend a year writing operas at King’s Theatre, London. He took such a liking to life and work in London that he chose to stay there, remaining for twenty years until his death in 1782.

It was in London that Johann Christian, in 1764, met the eight-year-old Mozart, with whom he improvised on at least one occasion. By then he had met the German composer and viol player Karl Friedrich Abel, with whom he founded the Bach-Abel concert series, which he also directed. He also wrote much music as a freelance composer, including sacred works, operas, symphonies, concertos, chamber music, and piano sonatas. In 1772 and 1775 two operas commissioned for Mannheim were performed in his presence: Temistocle (see Symphony no. 3 in D major) and Lucio Silla. In the 1770s he also traveled to Italy and to Paris, where he was commissioned to write the opera Amadis de Gaule, premièred in 1779 (see Symphony no. 5 in D major). He was thereupon commissioned to compose another opera, but died at the early age of forty-six before he could complete it. Though Johann Christian was the youngest of Bach’s four composer-sons, he was the first to die, followed by Wilhelm Friedemann (1710-1784), Carl Philipp Emmanuel (1714-1788), and Johann Christoph Friedrich (1732-1795). Of all the composers in the Bach family, he was the most cosmopolitan and enjoyed the greatest international esteem.

Johann Christian Bach wrote some forty symphonies, all of which bulk large in his oeuvre. The five appearing in our edition were composed beginning in 1762, and thus date from his London period. They well illustrate his development of the genre from the Italian theatrical sinfonia to the concert symphony, which he helped to establish as a form in its own right. Opera overtures were light music with brilliant orchestration and a straightforward formal design. In Bach’s day, their tripartite fast-slow-fast subdivision within a single movement evolved into three separate movements, generally marked allegro, andante, and allegro. Extremely slow expression marks such as adagio or grave were rare, as was the use of minor keys.

Bach’s symphonies are sometimes confusing in that some of their opus numbers were used more than once or, conversely, a single work appeared from different publishers with conflicting opus numbers. The numbering system used today is based on Ernest Warburton’s Thematic Catalogue (New York, 1999), published as vol. 48, no. 1, in his forty-eight-volume edition of The Collected Works of Johann Christian Bach (New York, 1984-99). To facilitate identification, I have indicated the exact location of each work on the sole complete recording of Bach’s symphonies and overtures, performed by The Hanover Band under Anthony Halstead (1994-2000) and issued as Complete Symphonies (5 CDs, cpo, 2002) and Complete Opera Overtures (3 CDs, cpo, 2003).

Symphony no. 1 in G minor, pp. 1-30

Allegro – Andante più tosto Adagio – Allegro molto

Composed in 1762-69

Published as op. 6, no. 6

Warburton no.: C12, contained in vol. 27

Complete Symphonies, CD 2, tracks 16-18

All six symphonies in op. 6 are scored for two oboes, two horns, strings, and basso continuo. No. 6 is Bach’s only symphony in a minor key, and is accordingly conceived in a dramatic and passionate vein fully in keeping with the Sturm und Drang. The opening movement is governed by two contrasting themes, the first rhythmically incisive and set in the tonic, the second (p. 26) gently flowing and set in the relative major (B-flat). In the development section (m. 68), the second part of the main theme appears seven times in various keys before returning to the tonic. There the second theme appears in a truncated recapitulation (m. 102) until the movement comes to an end with the first theme. This formal pattern already reveals hallmarks of classical sonata form.

The second movement, in C minor, discards the winds to produce a string quartet with basso continuo. Equally unusual is its distinctive expression mark Andante più tosto Adagio, requiring a character different from the customary Italian andante slow movements found in the first five symphonies of op. 6. Thus, when the theme recurs in m. 9, it is given to the low strings with a slow chromatic descent in the second violin. The heightened expression continues with forte accents in the Abgesang (m. 19). The second theme (m. 25) leads to a crescendo that suddenly ebbs away piano at the end, just as the movement as a whole fades into pianissimo after a crescendo.

The themes of the finale are not as distinctive as those of the first two movements. A propulsive first theme provides material that is taken up by the second theme (m. 15) in the relative major (B-flat). In any event, the formal sections of this movement take their bearings on the symphony’s opening movement. Thus, the development section (m. 38) consists of reiterated motifs (two-bar groups played nine times) that change only in their harmony; and the recapitulation (m. 61) opens with the second theme in the tonic. Instead of the grand crescendos of the Mannheim School, Bach preferred sharp dynamic contrasts and terrace dynamics, most forcefully displayed in the transition from the exposition to the development (fortissimo – piano – fortissimo). The ending fades away surprisingly in pianissimo, as in the second movement.

Symphony no. 2 in B-flat major, pp. 31-57

Allegro con spirito – Andante – Presto

Composed in 1767 or 1768

Published as op. 9, no. 1, and op. 21, no. 1

Warburton no.: C17a, contained in vol. 27

Complete Symphonies, CD 4, tracks 1-3

Unlike the first symphony in our volume, the opening movement of the B-flat major Symphony reveals a fully fledged sonata form. The exposition consists of two themes, the first played by the high strings in the tonic, the second by the two oboes in the dominant F major (m. 33). The development states the first theme in the dominant (m. 68), followed by the second in the tonic (m. 76), which it then proceeds to elaborate. The recapitulation (m. 111) is only slightly shorter than the exposition.

The melodious second movement is a slow minuet that dispenses with the two horns. It is set in rondo form: a threefold ritornello (mm. 1, 33-34, and 70-71) alternates twice with episodes (mm. 17 and 50) followed by a coda (m. 87) that takes up elements from both the ritornellos and the episodes. Everything is laid out in a clear and straightforward manner.

The Presto falls into two parts with complex subdivisions. Part I presents three eight-bar themes (mm. 1, 25, and 41), two eight-bar transitions (mm. 20 and 33), and a coda developed from the third theme (m. 49). This design, with its clearly articulated formal divisions, is altered in Part II. Like Part I, it opens with an initial theme, played twice, but stops after fourteen bars and bursts with a sudden forte into the development section (m. 72). This leads to the third theme (m. 80), again followed by a section of development. The second theme is postponed to bar 118. As in Part I, the music now proceeds in even eight-bar units: transition (m. 126), third theme (m. 134), and coda (m. 141). Bach thus employs a tripartite form inside a bipartite design and imparts a developmental character to the middle section (mm. 58-117), thereby turning the entire movement into a sort of sonata form. To put it simply, there is an exposition (themes 1-3), a development section, and a recapitulation (themes 2-3). If the repeat of Part II is ignored, everything darts by in barely three minutes.

Symphony no. 3 in D major, Overture to the opera Temistocle, pp. 59-84

Allegro di molto – Andante – Presto

Premièred at the Mannheim Court Theater on 5 November 1772

Warburton no.: G8, contained in vol. 7

Complete Opera Overtures, CD 3, tracks 4-6

The plot of Temistocle, a three-act opera seria on a libretto by Metastasio, takes place around 480 BCE in the days of the Persian Wars, when Greece was threatened with annexation by the Persian Empire. Its eponymous hero is the Greek commander Temistocles. For the overture’s outside movements Bach turned to the overture to his opera Caracatto, composed five years earlier. But rather than leaving the movements unchanged, he added trumpets and timpani to the score and altered the finale.

The festive opening movement is laid out in sonata form. The exposition presents two contrasting themes: a propulsive first theme in D major with a syncopated accompaniment, and a second theme in A major with simple rhythms and an antecedent that exudes tranquility (m. 27). The brief development section (m. 55) presents a new theme derived from the second. Both themes recur in the tonic in the recapitulation (m. 70). At each of its two occurrences, Bach varies the orchestration of the antecedent of the second theme as well as the third theme, which is based on the rhythm of the second (the strings are always present):

m. 27: oboes; m. 31: flutes and bassoons

m. 55: oboes and horns; m. 59: flutes

m. 100: oboes and bassoons; m. 104: flutes and horns

Bach thus employs every possible pairing of instruments accept for the two high ones (flutes and oboes) and the two low ones (bassoons and horns).

The second movement similarly exploits an alluring instrumental timbre, in this case three clarinetti d’amore, which have the pear-shaped bell of the oboe d’amore and sound more subdued than the standard clarinet. Bach’s Temistocle is one of the few pieces known to employ this instrument, which fell into disuse around 1800. In the overture’s middle movement the three clarinets form a unity, playing their theme four times unaccompanied by other instruments (mm. 12, 21, 76, and 84).

The final movement is a rondo with four ritornellos (mm. 1, 25, 45, and 89) and three episodes (mm. 17, 33, and 73), each set off by a quarter-note rest. The ritornellos are played forte by the full orchestra, the episodes piano by a concertino. The episodes, though short, increase regularly in length (8 – 12 – 16 mm.), while the ritornellos vary in length (16 – 8 – 28 – 27 mm.) and constantly alter the relations between antecedent and consequent: the first opens with the antecedent and ends with the consequent, the second presents both simultaneously, the third opens with the consequent, and the fourth is identical to the first with an appended coda.

Symphony no. 4 in E major for double orchestra, pp. 85-160

(Allegro moderato) – Andante – Tempo di Minuetto

Composed not earlier than 1772

Published as op. 18, no. 5

Warburton no.: C28, contained in vol. 28

Complete Symphonies, CD 5, tracks 13-15

The E-major Symphony is written for double orchestra. Each orchestra consists of a string quartet and a varied combination of winds, with Orchestra I scored for two oboes, one bassoon, and two horns, and Orchestra II for only two flutes. The second theme (m. 36) does not contrast with the first: both are melodious, the entire movement being conceived as a “singing allegro.” Between the two themes is a lengthy “Mannheim crescendo” from piano to fortissimo in which, rather than Orchestra II tagging after Orchestra I, the two orchestras gradually converge. Later there are passages in which Orchestra II takes the lead and Orchestra I follows suit (mm. 67 und 85). Usually, however, Orchestra I takes the lead, as in the second theme (m. 36) and the opening of the richly contrasting development section (m. 53), which opens with the consequent of the second theme (m. 53). The recapitulation (m. 126) likewise omits the antecedent of the second theme (m. 161). In the development, the contest between the two orchestras even congeals into a canonic texture, with Orchestra I taking the lead at one point (m. 79) and Orchestra II at another (m. 85). The entire movement is dominated by the strings; as in the early Neapolitan sinfonia, the winds merely fill in the harmony.

The relation between the groups of instruments is inverted in movement 2. Now it is the winds that dominate (albeit without the horns of movement 1), especially in the alternation of oboes and flutes, undergird by the strings. Bach continues to exploit the timbral contrast by having the strings of Orchestra II play con sordino until the final three bars and by making those of Orchestra I play pizzicato whenever they accompany thematic material in Orchestra I, as in mm. 9 to 15 and 63 to 96 in the consequent of the ritornello theme, and in mm. 32 to 41 of the episode theme. The movement is in rondo form with three ritornellos (mm. 1, 34, and 62) and two episodes (mm. 16 and 42) plus coda (m. 70). Unlike the third work in our volume, here the ritornellos are to be played piano and the episodes forte.

The finale is an E-major minuet laid out in ABA form, with the middle section set in the parallel minor (m. 83). Section A opens with four statements of an eight-bar theme. The second theme (m. 33) has a four-bar antecedent and an eight-bar consequent that is repeated to create a thematic complex of twenty bars. Following a thirteen-bar transition (m. 52) the first theme is restated, but with an altered orchestration paralleling the straightforward formal design. The middle section dispenses with horns and is itself, like the entire movement, set in ABA form: two eight-bar outside sections in E minor, played by the strings, flank a middle section set in the relative major (mm. 91-110) and dominated by the winds with string accompaniment. The A section is repeated intact (m. 119).

Symphony no. 5 in D major, pp. 161-94

Allegro con spirito – Andante – Allegretto – Allegro

Anonymous arrangement of sections from Bach’s opera Amadis de Gaule,

premièred at the Académie Royal de Musique, Paris, on 14 December 1779

Arrangement published as op. 18, no. 6

Warburton no. of arrangement: XC1, contained in vol. 28 (opera in vol. 10).

When correlated with the opera, the four movements have the numbers G39 (Overture 1),

G39 (Overture 2), G39/22 (Gavotte), and G39/41 (Gigue).

Complete Symphonies, CD 5, tracks 16-19; Complete Opera Overtures, CD 3, tracks 10-12

The D-major Symphony is the only one that Bach composed in four movements. It is an anonymous arrangement of sections from his final opera, Amadis de Gaule (1779), with the knight Amadis as its main protagonist. All movements except the second are laid out in rondo form. The first has three ritornellos (mm. 1, 50, and 109) and two episodes (mm. 33 and 84), each of which is followed by an area of transition (mm. 46 and 101). Unlike the opera overture, this work has repeats (mm. 62-72 = 73-82) and a simplified opening, both suggesting that an arranger was involved.

The second movement, too, reveals structural interventions from an arranger, who departed from the opera version of movement 2 by adding nine bars at the end and simplifying the orchestration. The movement is in ABA form with appended coda (m. 52). The reduction of the doubled flutes and oboes to one instrument each and the exclusion of the bassoon reinforce the movement’s almost intimate pastoral sound, which only becomes slightly more agitated in the middle section (m. 20). This section, too, is in ABA form, with the A sections dominated by the strings and the B section by the flute and oboe.

Movement 3, marked “Gavotte” in the opera, again has a different instrumental garb, now being a string quartet with oboe and bassoon. The winds appear only in the second episode, where the oboe plays a solo accompanied by the bassoon and the strings support the two winds with motifs from the first episode. The overall form has three ritornellos (mm. 1, 43, and 75) and two episodes (mm. 22 and 51).

The finale was originally a gigue occurring at the end of Act 2 in the opera. In the symphony it is again in rondo form with intervening sections. The two episodes suggest that the form has been expanded. The first (m. 28) consists not only of an antecedent and consequent, but also of an extension and retransition. The second (m. 40) is still more extended, with an eight-bar first section, eleven or twelve in the second, and a six-bar retransition. As in movement 3, there is a solo for the winds, in this case a trio of flute, oboe, and bassoon at the beginning of the second episode.

Harpsichord as Continuo Instrument?

In our edition, the editor Fritz Stein added a continuo realization in 1956 but left it to the discretion of the conductor whether to use it or not. The harpsichord was employed in England as a “conductor’s instrument” until the late eighteenth century. Though Bach’s early symphonies have a figured bass, it is uncertain whether it stems from him or his publishers. Practically none of his later symphonies has a figured bass. However, this does not argue against the use of a harpsichord, Stein adds, for Bach’s Six Favourite Overtures of 1770, likewise without figured bass, expressly call for an accompaniment “for the Harpsichord and Violoncello” on the title page. The first two symphonies in our volume have a figured bass; the final three do not. However, as Stein explains, they contain “harmonically empty passages that seem to presuppose a continuo instrument to flesh out the harmonies, which may have been supplied by the conductor at the harpsichord.”

Translation: Bradford Robinson