Vincent d’Indy

(b. Paris, 27 March 1851 – d. Paris, 2 December 1931)

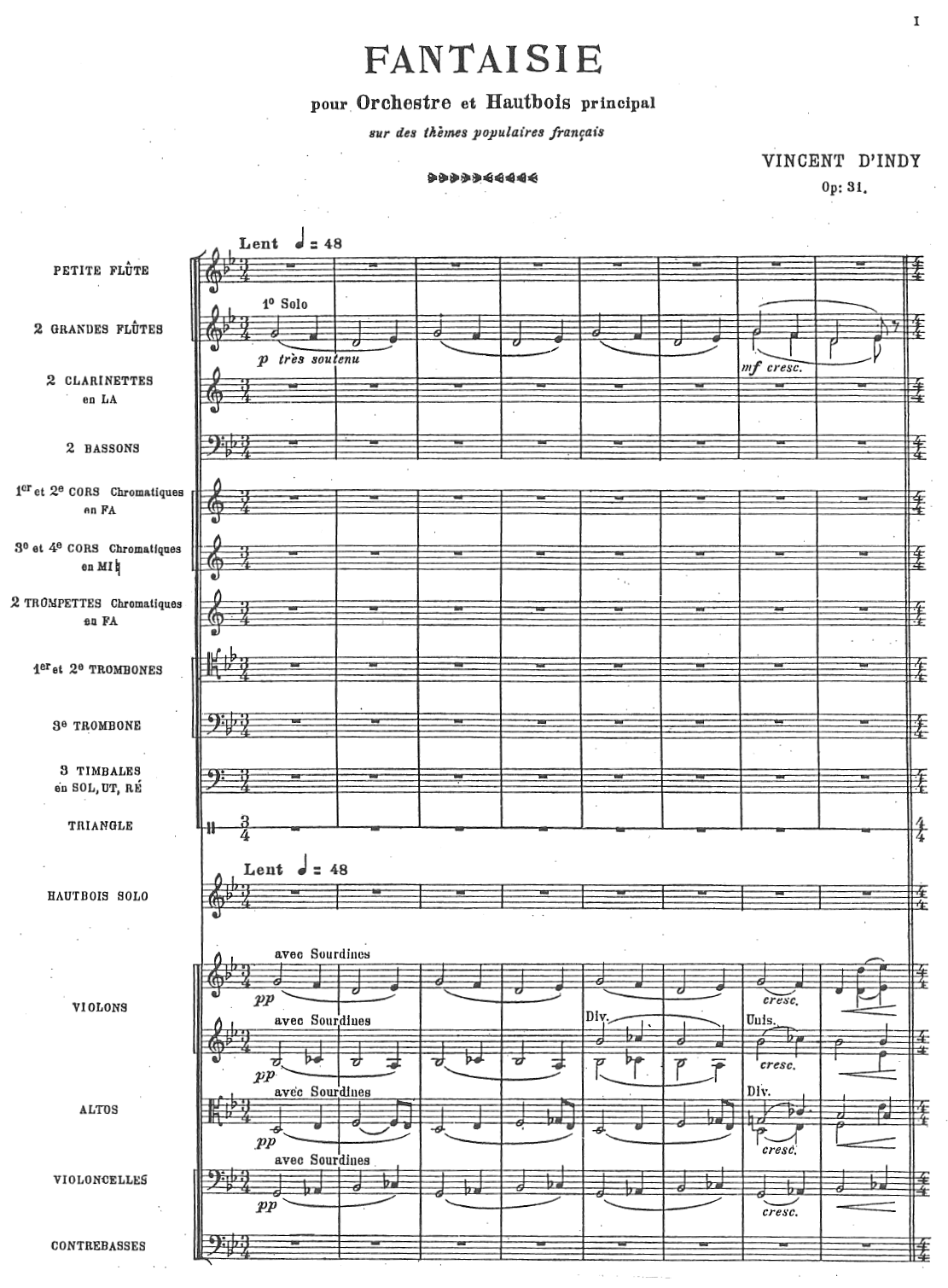

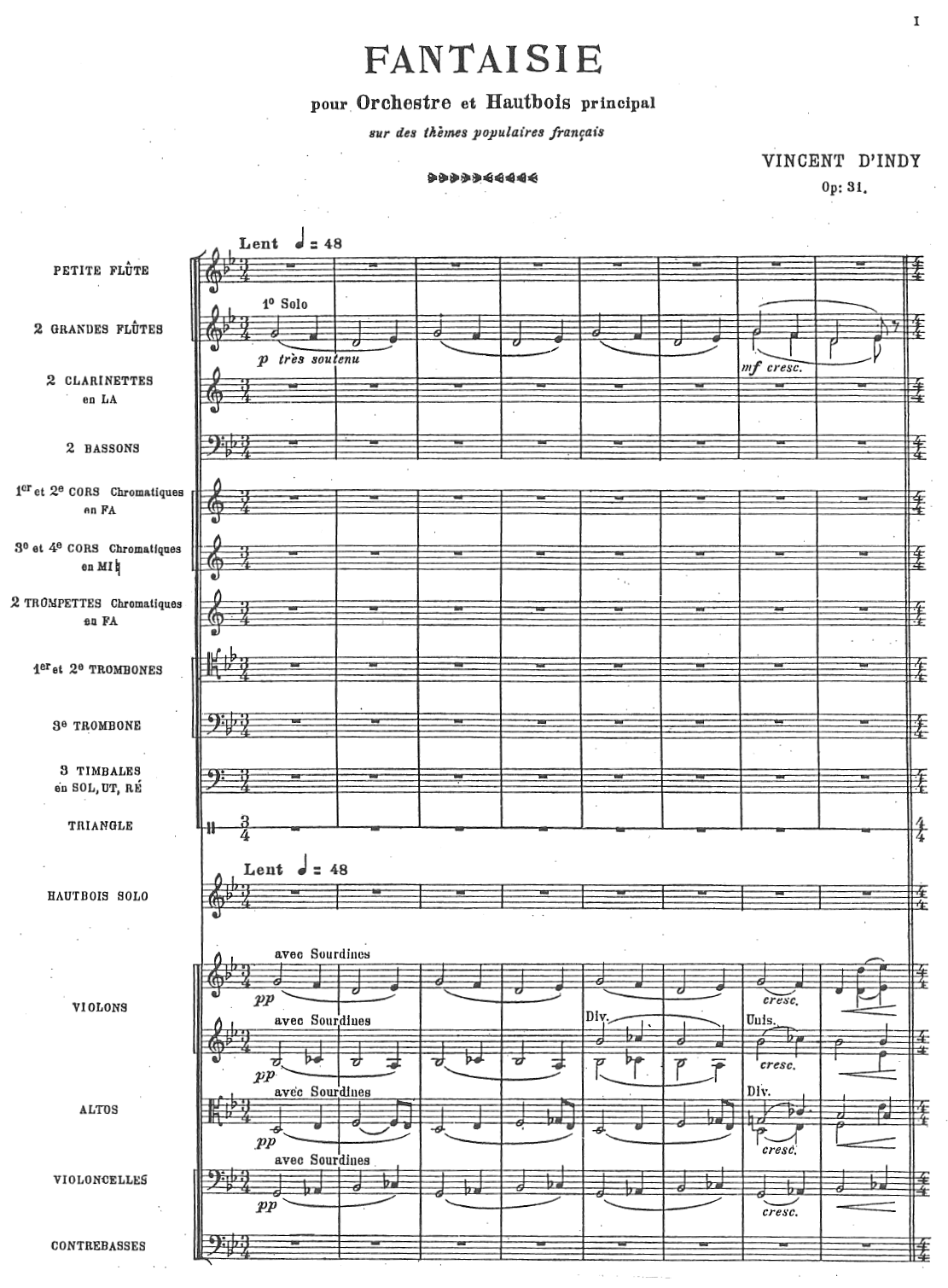

Fantaisie pour orchestre et hautbois principal sur des thèmes populaires français

Op. 31 (1888)

Preface

The mid-1880s marked an important turning point in the career of Vincent d’Indy. As a young composer, d’Indy had often looked to foreign sources for inspiration: he based his first major orchestral work, Wallenstein (1870-81), on the dramatic trilogy by Friedrich Schiller, and the Weberian La Fôret enchantée (1878) was inspired by a ballad by Ludwig Uhland. The composer’s obsession with the musical and dramatic ideas of Richard Wagner has also been amply documented. As he matured, however, d’Indy began to employ materials from his native France—in particular, folk songs from his ancestral homeland in the Ardèche (Vivarais) region—with increasing frequency. D’Indy’s biographer Léon Vallas recounts a formative encounter that presaged the composer’s deepening fascination with traditional French music. While hiking in the Cévennes one summer day, d’Indy overheard a melody sung from afar, which he notated in a scrapbook. He soon set to work on a composition based on this folk tune.1 D’Indy initially envisioned a fantaisie for piano and orchestra, but eventually decided that the material was better suited for a symphony. The resulting piece, the Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français (also known as the Symphonie cévenole, 1886), represented a breakthrough in d’Indy’s compositional style, and remains his best known work today.

D’Indy’s turn to regional folk song coincided with a growing interest among musicians, intellectuals, and political leaders in the music of the French provinces. Many French composers had incorporated regional melodies into their works in the preceding years, including Georges Bizet (L’Arlésienne, 1872), Édouard Lalo (Le Roi d’Ys, 1875-88), Jules Massenet (Scènes alsaciennes, 1882), and Camille Saint-Saëns (Rhapsodie d’Auvergne, 1884). The vogue for folk music intensified in the mid-1880s. As Jann Pasler has noted, political leaders from across the ideological spectrum shared a desire to promote indigenous music: republicans looked to folk song to cultivate a shared sense of the nation’s past, whereas conservative elites such as Maurice Barrès sought to use traditional melodies from the provinces to preserve regional identity and languages.2 In 1885, the Société des traditions populaires was founded to facilitate the collection and analysis of chansons populaires, and the Institut de France established the Prix Bordin for the best study of the genre. In response to this competition, the musicologist and composer Julien Tiersot undertook a comprehensive investigation of regional folk melodies, publishing a compendium of songs in Les Mélodies populaires des provinces de France (1887) and analyzing them in his influential Histoire de la chanson populaire en France (1889).

D’Indy contributed to the study of folk music as well. In 1887, he began to collect melodies from the Virarais and Vercors, two regions where no researchers had yet done systematic work. The composer published a volume of these songs in collaboration with Tiersot in 1892, reissuing them with optional harmonization and piano accompaniment in 1900.3 D’Indy believed that traditional songs revealed the essence of a region’s identity, stating in the preface to the latter volume that his aim was to “unveil the Vivarais soul” (dévoiler l’âme vivaroise). His motivations also had a moral dimension. As he noted in his Cours de composition musicale, d’Indy contended that folk song had its origins in plainchant, and was therefore linked to the religious faith that was central to his conception of art.4 In addition to collecting regional melodies, d’Indy featured them in several of his compositions, including the Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français, the Fantaisie sur des thèmes populaires français, the incidental music for Karadec (1890), and his magnum opus, the opera Fervaal (1888-95).

D’Indy composed the Fantaisie in the summer of 1888, alongside preparatory efforts on Fervaal. His work on these compositions took place at Chabret, the family estate in the Ardèche where the composer had spent his summers as a child, and a beloved refuge from the distractions of Paris. The first performance of the Fantaisie took place on 23 December of the same year at the Concerts Lamoureux in Paris. The Belgian oboist Guillaume Guidé, professor at the Brussels Conservatory and the work’s dedicatee, performed the solo part; Charles Lamoureux conducted. In subsequent years, d’Indy himself conducted the Fantaisie on numerous occasions, often with Guidé as soloist.

In his discussion of the Fantaisie in the Cours de composition musicale, d’Indy describes the work as a “rhapsody” on four themes.5 The piece begins with a slow introduction in G minor based on a fragment of theme 1. As Vallas has noted, this repeated opening gesture (G, F, D, E-flat) bears a resemblance to the bien-aimée motive from d’Indy’s Poème des montagnes (1881), a figure that was intended to represent the composer’s beloved wife Isabelle.6 The oboe presents the theme proper on page 3, followed by a contrasting modulatory idea at rehearsal 3 (p. 5).

Themes 2 and 3 are transcriptions of folk melodies d’Indy collected during his research in the Vivarais, and appear in his published anthologies of chansons populaires.7 Both are examples of the bourrée montagnarde, which the composer describes as “the dance par excellence of our highlanders.” Theme 2, first heard at rehearsal 5 (p. 8) of the Fantaisie, is a joyous, hemiola-inflected theme in G major. After a transition derived from the introductory modulatory idea, d’Indy presents theme 3, more severe in character, at the Modérément lent (p. 16). An initial statement of this theme in C minor is followed by a repetition in B minor, against which the oboe plays a counterpoint derived from theme 1. The music turns to B major with the first presentation of theme 4, a gentle melody that revolves around the mediant (d’Indy indicates très doux), three measures before rehearsal 10 (p. 17).

After a brief developmental section (Vite, p. 19), d’Indy presents a variant of theme 2 (Plus modéré, p. 22). This modified statement resembles the variations on the original tune the composer heard during his research in the Vivarais, suggesting that he sought to retain the folk ethos of his source material. In his 1900 volume of chansons populaires, d’Indy includes several of these variations and explains how the melody was traditionally performed: “The singer responsible for the dance, after repeating the basic theme ad nauseam, without any change, suddenly begins it again in a high octave, in a falsetto voice, elaborating it with a profusion of repeated notes, tongue clicks, and various ornaments, while the assistants seated at the drinking tables provide the rhythm for the dancers’ steps in a most curious manner, with repeated blows of the handles of their cutlery boxes. These variations usually indicate the end of the dance; I have tried to reproduce the various rhythms in the harmonic accompaniment included with these tunes.”8

Thereafter, d’Indy reprises the remaining thematic elements in order: an emphatic statement of theme 3 in counterpoint with the opening motive of theme 1 (Assez lent et majestueux, p. 27), followed by a valedictory presentation of theme 4 in the home key of G major (p. 29). Fragments of themes 1 and 2 bring the Fantaisie to a serene close.

Mark Seto, 2013

1 Léon Vallas, Vincent d’Indy, vol. 1 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1946), 229.

2 See Jann Pasler, “Race and Nation: Musical Acclimatization and the Chansons Populaires in Third Republic France,” in Western Music and Race, ed. Julie Brown (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 147-67; and idem., Composing the Citizen: Music as Public Utility in Third Republic France (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 352-57. For a comparison of the regionalist attitudes of d’Indy and Barrès, see James Ross, “D’Indy’s Fervaal: Reconstructing French Identity at the ‘Fin de Siècle’,” Music & Letters 84, no. 2 (May 2003): 209-40.

3 Vincent d’Indy, Chansons populaires recueillies dans le Vivarais et le Vercors (Paris: Heugel, 1892); and Chansons populaires du Vivarais, op. 52 (Paris: Durand, 1900).

4 D’Indy, Cours de composition musicale, vol. 1 (Paris: Durand, 1903), 84.

5 D’Indy, Cours de composition musicale, vol. 2, part 2 (Paris: Durand, 1948), 314.

6 Vallas, Vincent d’Indy, vol. 2 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1950), 134-35.

7 D’Indy, Chansons populaires recueillies dans le Vivarais et le Vercors, 48-49; Chansons Populaires du Vivarais, op. 52, 154-55.

8 D’Indy, Chansons Populaires du Vivarais, op. 52, 152.

For performance material please contact the publisher Durand, Paris.

Vincent d’Indy

(geb. Paris, 27 März 1851 – gest. Paris, 2 Dezember 1931)

Fantaisie pour orchestre et hautbois principal sur des thèmes populaires français

op. 31 (1888)

Vorwort

Die mittleren 1880er Jahre markierten einen Wendepunkt in der Karriere von Vincent d’Indy. Als junger Komponist war d’Indy beständig auf der Suche nach Inspirationen aus der Fremde: so fußte sein erstes gewichtiges Orchesterwerk Wallenstein (1870-81) auf der dramatischen Trilogie von Friedrich Schiller, und das an Weber orientierte La Fôret enchantée (1878) war von einer Ballade Ludwig Uhlands angeregt. Auch ist die Leidenschaft des Komponisten für die musikalischen und dramatischen Ideen Richard Wagners ausreichend dokumentiert. Mit zunehmender Reife jedoch begann er, Material aus seiner französischen Heimat einzusetzen - insbesondere Volksmelodien aus der Ardèche (Vivarais), dem Land seiner Vorfahren - , und das mit zunehmender Regelmässigkeit. D’Indys Biograph Léon Vallas erinnert sich an eine prägende Begegnung, die die sich vertiefende Faszination des Komponisten für die traditionelle französische Musik vorhersagte. Während einer Wanderung durch die Chevennen vernahm d’Indy eines Sommertages eine Melodie aus der Ferne, die er in sein Notizbuch notierte. Schon bald machte er sich an die Arbeit, diese Volksweise zu vertonen.1 Als erstes stellte er sich eine fantaisie für Klavier und Orchester vor, entschied aber letztendlich, dass dieser Stoff sich besser für eine Symphonie eigne. Das daraus resultierende Stück, die Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français (bekannt auch als Symphonie cévenole, 1886), stellte einen Durchbruch in d’Indys Kompositionsstil dar und bleibt bis heute eines seiner bekanntesten Werk.

D’Indys Hinwendung zur regionalen Volksmusik ging einher mit einem wachsenden Interesse unter Musikern, Intellektuellen und politischen Führern an der Musik der Provinzen. Viele französische Komponisten hatten in den vergangenen Jahren ihren Werken regionale Melodien einverleibt, darunter Georges Bizet (L’Arlésienne, 1872), Édouard Lalo (Le Roi d’Ys, 1875-88), Jules Massenet (Scènes alsaciennes, 1882) und Camille Saint-Saëns (Rhapsodie d’Auvergne, 1884). Die Begeisterung für Volksmusik sollte sich in der Mitte der 1880er noch verstärken. Wie Jann Pasler berichtet, vereinte Politiker aus dem gesamten ideologischen Spektrum der Wunsch, die Musik der verschiedenen Landstriche zu fördern: die Republikaner suchten mit dem Volkslied einen gemeinsamen Sinn für die Vergangenheit der Nation zu kultivieren, während die konservativen Eliten wie zum Beispiel Maurice Barrès in den traditionellen Melodien der Provinzen eine Möglichkeit wähnten, die regionale Identität und Sprache zu bewahren.2 Im Jahr 1885 wurde die Société des traditions populaires gegründet, um die Sammlung und Analyse von chansons populaires zu ermöglichen, und das Institut de France lobte den Prix Bordin für die beste Studie innerhalb des Genre aus. Als Entgegnung auf diesen Wettbewerb unternahm der Musikwissenschaftler und Komponist Julien Tiersot eine umfassende Untersuchung regionaler Volksmusiken und veröffentlichte eine Sammlung von Liedern in Les Mélodies populaires des provinces de France (1887), die er in seiner einflussreichen Histoire de la chanson populaire en France (1889) analysierte.

Auch d’Indy leistete seinen Beitrag zur Erforschung der Volksmusik. 1887 begann er, Melodien aus Virarais und Vercors zu sammeln, zwei Landstriche, die von Musikforschern bisher nicht systematisch erkundet worden waren. Gemeinsam mit Tiersot veröffentlichte der Komponist 1892 einen Band dieser Lieder, eine Neuauflage mit optionaler Harmonisierung und Klavierbegleitung erschien 1900.3 D’Indy glaubte, dass das traditionelle Liedgut das Wesen der Identität einer Region offenbare, und bemerkt im Vorwort zur letzteren Ausgabe, dass es sein Ziel sei, die “Seele des Vivareis zu entschleiern” (dévoiler l’âme vivaroise). Seine Motivation hatte auch eine moralische Dimension. Wie in seinem Cours de composition musicale zu lesen ist, behauptete d’Indy, dass die Volkslieder ihren Ursprung im gregorianischen Gesang hätten und auf diese Weise mit einer religiösen Anschauung verbunden seien, die im Zentrum seiner Konzeption von Kunst steht.4 Neben seiner Arbeit als Sammler heimischer Melodien stellte er sie auch in etlichen seiner Kompositionen vor, darunter in der Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français, in der Schauspielmusik für Karadec (1890) und in seinem magnum opus, der Oper Fervaal (1888-95).

D’Indy komponierte die Fantaisie im Sommer 1888, zeitgleich mit seinen Vorbereitungen zu Fervaal. Die Arbeit an diesen Werken fand in Chabret statt, dem Familiensitz in der Ardèche, seinem geliebten Rückzugsort von den Pariser Zerstreuungen, wo der Komponist bereits seine Sommer als Kind verbrachte hatte. Die Erstaufführung der Fantaisie fand am 23. Dezember desselben Jahres anlässlich der Concerts Lamoureux in Paris statt. Der belgische Oboist Guillaume Guidé, Professor am Brüsseler Konservatorium und Widmungsträger des Werks, übernahm den Solopart; Charles Lamoureux dirigierte. In den folgenden Jahren leitete d’Indy die Fantaisie selbst bei zahlreichen Gelegenheiten, oft gemeinsam mit Guidé als Solist.

In seiner Diskussion der Fantaisie im Cours de composition musicale beschreibt der Komponist das Werk als “Rhapsodie” aus vier Themen.5 Das Stück beginnt mit einer langsamen Einleitung in g - Moll, basierend auf einem Fragment von Thema 1. Wie Vallas bemerkt, ähnelt die sich wiederholende Anfangsgeste (G,F,D,Es) dem bien-aimée - Motiv aus d’Indys Poème des montagnes (1881), eine musikalische Figur, die die geliebte Ehefrau des Komponisten repräsentieren sollte.6 Auf Seite 3 spielt die Oboe das Thema als Ganzes, gefolgt von einer kontrastierenden, modulatorischen Idee bei Ziffer 3 (Seite 5).

Thema 2 und 3 sind Transkriptionen von Volksmelodien, die d’Indy während seiner Forschungen im Vivarais sammelte und die in seinen Anthologien der chansons populaires erschienen sind.7 Beide Motive sind Beispiele für das bourrée montagnarde, das der Komponist als “den klassischen Tanz der Bergbewohner” bezeichnet. Thema 2, das zum ersten Mal bei Ziffer 5 (Seite 8) anhebt, ist ein frohes, hemiolisches Motiv in G - Dur. Nach einem Übergang, der sich aus der modulierenden Idee der Introduktion herleitet, lässt d’Indy Thema 3 folgen, eher ernst im Charakter, bei Modérément lent (Seite 16). Einer ersten Vorstellung des Themas in c - Moll folgt dessen Wiederholung in h - Moll, die Oboe setzt hier einen Kontrapunkt, der aus dem ersten Thema abgeleitet ist. Die Musik entwickelt sich nach H - Dur mit dem ersten Erklingen von Thema 4, einer sanften Melodie, die die Mediante umkreist (d’Indy verlangt très doux), drei Takte vor Ziffer 10 (Seite 17).

Nach einer kurzen Durchführung (Vite, Seite. 19) präsentiert d’Indy eine Variante von Thema 2 (Plus modéré, Seite. 22). Diese modifizierte Version ähnelt den Variationen der originalen Melodien, die der Komponist während seiner Forschungen im Vivarais zu hören bekam und erinnert an d’Indys Absicht, den volksmusikalischen Ethos des Quellenmaterials zu bewahren. In seiner 1900er Ausgabe der chansons populaires versammelt d’Indy zahlreiche jener Variationen und erklärt, wie die Melodie ursprünglich aufgeführt wurde: “Der Sänger, verantwortlich für den Tanz, beginnt, nachdem er das Hauptthema ohne Unterlass und ohne jegliche Veränderung wiederholt hat, das Motiv in einer hohen Oktave im Falsett, arbeitet es mit einer Überfülle an wiederholten Noten aus, mit Zungenschnalzern und verschiedensten Ornamenten, während seine Assitenten, die an den Trinktischen sitzen, auf eine höchst merkwürdige Art für den Rhythmus sorgen, indem sie nämlich wiederholt auf die Griffe der Besteckkästen schlagen. Diese Variationen bedeuten normalerweise das Ende des Tanzes; Ich habe versucht, die unterschiedlichen Rhythemn in der harmonischen Begleitung dieser Weisen wiederzugeben.”8

Danach wiederholt d’Indy die verbleibenden thematischen Elemente in anfänglicher Reihenfolge: eine emphatische Präsentation des dritten Themas im Kontrapunkt mit dem eröffnenden Motiv von Thema 1 (Assez lent et majestueux, Seite. 27), gefolgt von einer Abschiedsvorstellung des vierten Motivs in der Ursprungstonart G -Dur (Seite 29). Fragmente der Themen 1 und 2 bringen die Fantaisie schliesslich zu einem heiteren Ende.

Mark Seto, 2013

1 Léon Vallas, Vincent d’Indy, vol. 1 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1946), 229.

2 Siehe Jann Pasler, “Race and Nation: Musical Acclimatization and the Chansons Populaires in Third Republic France,” in Western Music and Race, hrsg. Julie Brown (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 147-67; und idem., Composing the Citizen: Music as Public Utility in Third Republic France (Berkeley und Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 352-57. Für einen Vergleich der regionalen Besonderheiten von d’Indy und Barrès, siehe James Ross, “D’Indy’s Fervaal: Reconstructing French Identity at the ‘Fin de Siècle’,” Music & Letters 84, Nr. 2 (May 2003): 209-40.

3 Vincent d’Indy, Chansons populaires recueillies dans le Vivarais et le Vercors (Paris: Heugel, 1892); und Chansons populaires du Vivarais, op. 52 (Paris: Durand, 1900).

4 D’Indy, Cours de composition musicale, vol. 1 (Paris: Durand, 1903), 84.

5 D’Indy, Cours de composition musicale, vol. 2, Teil 2 (Paris: Durand, 1948), 314.

6 Vallas, Vincent d’Indy, vol. 2 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1950), 134-35.

7 D’Indy, Chansons populaires recueillies dans le Vivarais et le Vercors, 48-49; Chansons Populaires du Vivarais, op. 52, 154-55.

8 D’Indy, Chansons Populaires du Vivarais, op. 52, 152.

Wegen Aufführungsmaterial wenden Sie sich bitte an Durand, Paris.