Vincent d‘Indy

(27. März 1851 – 2. Dezember 1851)

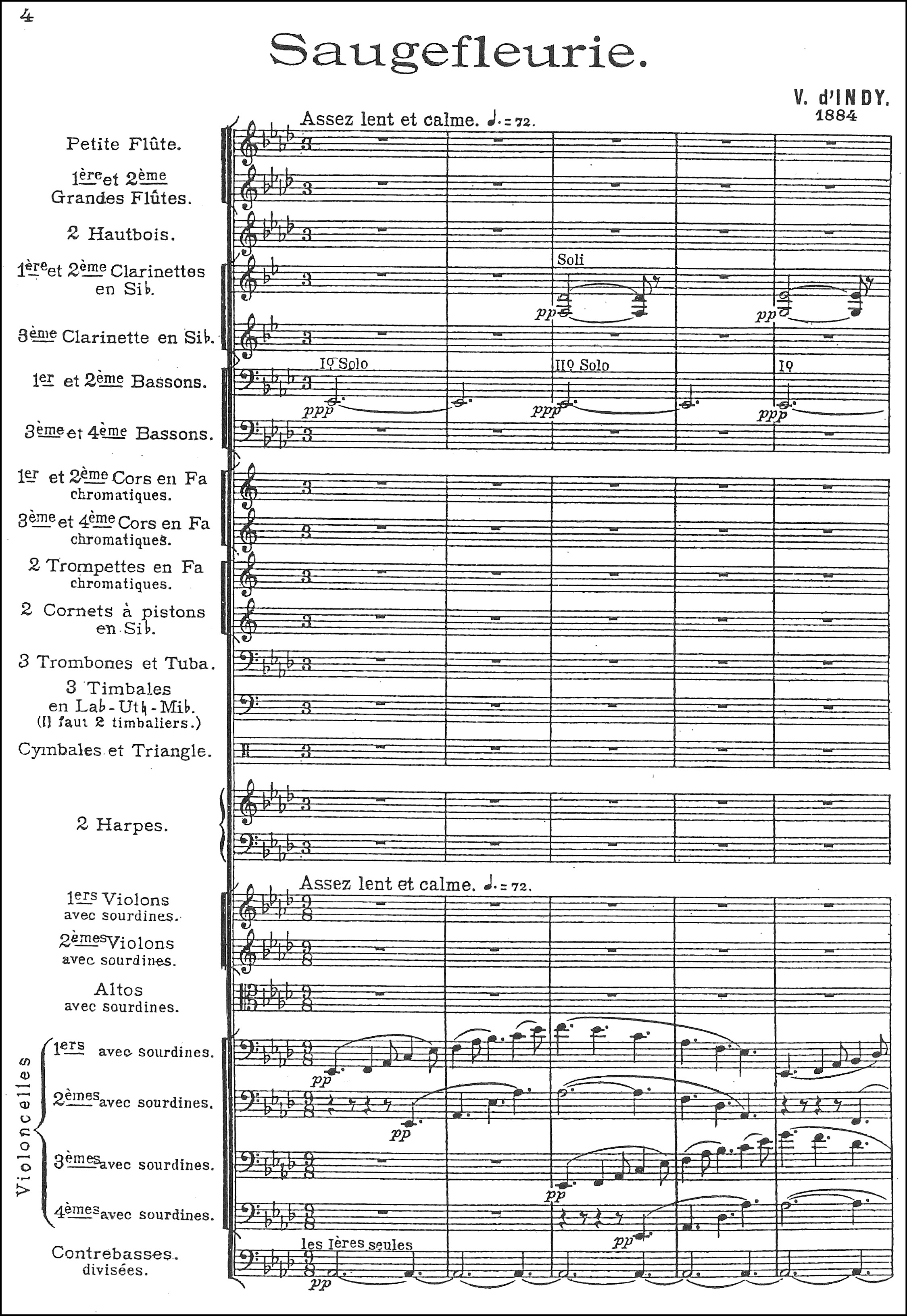

Saugefleurie

Legende für Orchester nach Robert de Bonnières (1884)

Vorwort

Biographischer Abriss

Die sinfonische Dichtung Saugefleurie zählt zu einem der frühen Erfolge des französischen Komponisten Vincent d’Indy. D‘Indy schrieb sie 1884 mit bereits 33 Jahren, nachdem er zunächst eine Militärkarriere in Betracht gezogen hatte. Nach seinem Dienst im deutsch-französischen Krieg 1870/71 entschied er sich aber gegen eine militärische Laufbahn und für die Musik. „“Ich möchte mich ab heute nur der Kunst, der Musik widmen, nicht nur als einfacher Amateur, sondern als Künstler, ich beschließe dies ganz förmlich und ich werde diese Entscheidung nicht widerrufen.”1 hielt er am 26. September 1871 in seinem Tagebuch fest. Von diesem Zeitpunkt an verfolgte Vincent d’Indy seine musikalische Laufbahn mit großem Ehrgeiz. Durch seinen Nachbarn und Freund Henri Duparc entsteht der Kontakt zu César Franck, bei dem er von 1873-1875 Orgel- und Kompositionsunterricht nahm. D’Indy war nie offizieller Student des Pariser Conservatoire, stattdessen zog er den Unterricht bei Franck vor und suchte sich eigene Möglichkeiten, um seine musikalischen Kenntnisse und Fähigkeiten auszubauen: 1873 reist er zu Franz Liszt nach Weimar und verbringt dort zwei Monate im Kreise von dessen Privatschülern, er nimmt die Stelle eines Titularorganisten an der Kirche Saint-Leu-Traverny an, spielt als Paukist am Théâtre-Italien und der Opéra Comique, ist Chordirigent bei den Concerts Pasdeloup und den Concerts Colonne, tritt als Pianist auf und leitet Laienmusikkonzerte. Seit 1876 engagierte er sich als Sekretär in der Société nationale de musique, die sich für die Aufführung zeitgenössischer französischer, aber auch ausländischer Komponisten in Paris einsetzte. In den 1870er Jahren gelangten d’Indys eigene Kompositionen zum ersten Mal öffentlich zur Aufführung, so erklangen zum Beispiel die Orchesterwerke La forêt enchantée op. 8 und Wallenstein in den Concerts Pasdeloup in Paris. Außerdem unternahm d‘Indy in diesem Jahrzehnt viele Reisen, er fuhr nach Italien, Österreich, in die Schweiz und nach Deutschland – und sehr häufig nach Bayreuth zu den Festspielen. 1876 war er bei der Eröffnungsvorstellung mit dem Rings des Nibelungen und noch 1882 lernte er dort Richard Wagner kennen, dessen Musik für ihn zeit seines Lebens eine wichtige Rolle spielte. Erst Anfang der 1880er Jahre wurde d‘Indy einer breiteren Öffentlichkeit in Paris und Frankreich bekannt: Mit der opéra comique Attendez-moi sous l’orme op. 14 machte der damals 31jährige 1882 zum ersten Mal als Komponist auf sich aufmerksam und spätestens 1885, als er mit seiner légende dramatique Le Chant de la Cloche den Prix de la Ville de Paris gewinnt, galt er als einer der vielversprechendsten Vertreter seiner Generation.

Entstehung, Uraufführung und Rezeption

Kurz vor dem Durchbruch als Komponist entstand Saugefleurie op. 21, an einem Wendepunkt seiner musikalischen Karriere. D’Indy komponierte das Stück im Laufe des Jahres 1884 und am 25. Januar 1885 wurde es bei den Concerts Lamoureux im Château-d’Eau uraufgeführt2. Die Concerts Lamoureux waren eine Konzertgesellschaft, die der Geiger und Dirigent Charles Lamoureux 1881 ins Leben gerufen hatte. Lamoureux, Widmungsträger der Komposition und wie d’Indy ein Verehrer der Werke von Richard Wagner, hatte in Frankreich die ersten Aufführungen der Musikdramen des Deutschen dirigiert. Eingehende Kritiken zur Uraufführung von Saugefleurie ließen sich nicht finden, aber eine Besprechung des Konzerts einige Wochen später fällt ein ernüchterndes Urteil: «»Saugefleurie, in den Concerts Lamoureux gespielt, ist eine erbärmliche Sinfonische Dichtung mit deskriptivem Programm; es gibt einige hübsche Effekte im Timbre und geistreiche Harmonien, die aber ohne Skrupel einfach aus den Partituren von Wagner herausgeschnitten sind.»3 Belege für die Entstehungsgeschichte und Dokumente von d’Indy selbst darüber oder die Uraufführung sind bisher nicht bekannt.

Eine verlässliche und umfassende Untersuchung der Rezeption liegt noch nicht vor, es lassen sich aber doch einige Aufführungen belegen, sodass davon ausgegangen werden kann, dass Saugefleurie zu Lebzeiten d‘Indys in relativer Regelmäßigkeit im Konzert erklang. Am 22. Dezember 1889 wurde es im Grand Concert Extraordinaire der Association Artistique Angers wohl das erste Mal außerhalb von Paris aufgeführt.4 In den 90er Jahren gab es einige Aufführungen, so zum Beispiel 1895 in Nancy bei einem Vincent d’Indy gewidmeten Festival.5 Auch nach der Jahrhundertwende blieb Saugefleurie auf den Spielplänen, am 19. November 1905 erklang es bei den Concerts Colonne6, im folgenden Jahr am 1. Juli beim 10. Konzert des Conservatoires in Nancy unter der Leitung von Guy de Ropartz7. 1907 stand das Werk unter der Leitung von d’Indy selbst am 6. März beim 7. Konzert der Société des Grands Concerts in Lyon zusammen mit Istar und der 8. Symphonie von Beethoven auf dem Programm.8 D‘Indy setzte Saugefleurie zudem bei seiner USA-Reise 1906 auf sein Konzertprogramm,9 was als Zeichen dafür gewertet werden kann, dass dieses frühe Werk für ihn auch später ein wichtige Rolle unter seinen Kompositionen einnahm und nicht etwa als „Jugendsünde“ abgetan wurde. Saugefleurie zählt demnach weder zu den erfolgreichsten Stücken noch zum Gegenteil. Das kurze Orchesterwerk dürfte in Frankreich also durchaus bekannt gewesen sein.

Textvorlage und ihre Umsetzung in Musik

Der Komposition liegt ein Text aus den Contes des Fées von Robert de Bonnières zugrunde, der hier wiedergegeben sei:10

Alors vivat, sans crédit ni richesse,

Une fée humble et seule ........

............. Saugefleurie - -

Tel est son nom - - était charmante à voir.

Au bord d’un lac tout fleuri de jonquilles,

Elle habitait le tronc d’un saule creux

Et ne quittait son réduit ténébreux

Plus que ne font les perles leurs coquilles.

Mais, un beau jour que, chassant par le bois

Avec sa meute en superbe équipage,

Le Fils du Roi menait à grand tapage

Du bois au lac un dix-cors aux abois,

Pour voir les chiens et la belle poursuite

Et les pourpoints brillants des cavaliers,

Elle quitte son arbre ...........

Le Fils du Roi ..................

En voyant mieux un si charmant visage,

S’arrêta court et la dévisagea --

Sauge, sans plus se cacher dans les branches

En le voyant si beau, de son côté

Le regardait, devant elle arrêté,

Droit dans les yeux, de ses prunelles franches --

Naïf amour par pudeur s’enhardit :

Le fils du Roi baissa les yeux par contre.

...............................

Tous deux s’aimaient et ne s’étaient rien dit.

...............................

- - Aimer un homme était un cas de mort

Pour Sauge ....................

...............................

Sauge, pourtant, demeurait bouche close,

Et, de cela, ne voulait seulement

Qu’aimer le prince et mourir en l’aimant.

...............................

Or, nul pouvoir ne pouvait s’opposer

Au libre emploi de son gentil courage

Non plus qu’au choix de son premier baiser.

...............................

... Seigneur, les beaux jours sont comptés …

...............................

«N’aimez-vous point la belle solitude,

Et des amants n’est-ce plus l’habitude

De mieux s’aimer quand l’amour est secret?

Restons ici sans peur, si bon vous semble;

Nos yeux pourront se parler à loisir,

Et nous n’aurons de si charmant plaisir

Que seul à seul à demeurer ensemble.

Auprès de vous je sens mon coeur léger,

Légère est l’heure aussi qui me convie - -

O mon Seigneur, je vous donne ma vie...

Prenez-la donc, mais sans m’interroger!»

...............................

- - AMOUR et MORT sont toujours à l’affût

Ne croyez pas que celle que je pleure

Fut épargnée,

Elle sécha sur l’heure

Comme une fleur de Sauge qu’elle fut.

Im Conte de Fée von Robert de Bonnières geht es um eine junge Fee, Saugefleurie, die zurückgezogen im Stamm einer Weide an einem See im Wald lebt. Eines Tages hört sie Jagdlärm – der Sohn des Königs verfolgt einen Hirschen durch den Wald. Entzückt von Saugefleuries Anblick bleibt der Prinz stehen. Obwohl es für Feen den Tod bedeutet, einen Mann zu lieben, entscheidet sich Saugefleurie gegen die Unsterblichkeit, um für einen Moment das Herz des Prinzen zu besitzen. Doch nach einer Liebesszene stirbt Saugefleurie, das letzte Bild des Gedichtes vergleicht ihren Tod mit dem Vertrocknen einer Blume (Sauge = Salbei).

Vincent d’Indy greift sich für seine Musik aus diesem deskriptiven Gedicht zwei zentrale Themen heraus, die Melancholie und Träumerei von Saugefleurie und die Jagd. Das Stück beginnt mit einem wiegenden Thema in den geteilten Violoncelli, es evoziert mit seinen fließenden Auf- und Ab-Bewegungen das erste Bild der Textvorlage – Saugefleurie vor sich hin träumend, am Ufer eines Sees, mit blühenden Blumen, nur selten verlässt sie ihren schützenden Baumstamm – und hat wohl nicht von ungefähr Ähnlichkeit mit dem Vorspiel des Rheingolds, war d’Indy doch ein großer Verehrer und Kenner von Wagners Musikdramen. Bald erhebt sich in der Solobratsche ein zauberhafter kantables Thema (S. 6), später tritt die Flöte hinzu (ab S. 8); durch diesen Kontrast zwischen den womöglich die Fee symbolisierenden Soloinstrumenten und dem ruhigen Klangteppich evoziert d‘Indy geschickt das Bild einer im Wald umherirrenden Fee. Die Jagd des Prinzen kündigt sich in der Musik durch Hornappelle an (S. 10), und auch hier lässt sich eine Ähnlichkeit mit Wagners Siegfried nicht leugnen. Nach einer romantischen Liebesszene schließt sich der Kreis, mit Hörnerappellen reitet der Prinz weg und die Fee stirbt mit der Wiederkehr der Bratschenmelodie des Anfangs, diesmal etwas melancholischer, harmonisch düsterer und schmerzlicher.

Es gälte zu klären, wie genau sich Vincent d‘Indy der Instrumentation und Leitmotive von Wagners Ring des Nibelungen bedient und inwiefern diese Legende für Orchester in einer Reihe mit Franz Liszts sinfonischen Dichtungen sowie der französischen Programmmusik steht.

Anita Svach, 2013

1 Marie d‘Indy, Vincent d’Indy. Ma Vie, Journal de Jeunesse. Correspondance famliale et intime 1851-1931. Ausgewählt, hrsg. und kommentiert von Marie d’Indy, Paris 2001, S. 143.

2 Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1885, S. 552.

3 La Revue Moderniste, April 1885, S. 50.

4 Angers Artiste, Nr. 12, Samstag 21. Dezember 1889, Titelseite.

5 Nachvollziehbar durch einen Artikel von René d’Avril in Le Mercure Musical, Nr. 13, 1. Juli 1906, S. 40.

6Louis Laloy, Revue de la Quinzaine, in: Le Mercure Musical, 15. Mai 1905 bis 15. Dezember 1905, S. 584.

7 René d‘Avril, Revue de la Quinzaine, in: Le Mercure Musical, 1. Juli 1906, S. 40.

8 Revue française de musique, Lyon/Paris, 28. Oktober 1906, S. 91 und 3. März 1907, S. 624.

9 Ch. M. L., Revue de la Quinzaine, in: Le Mercure Musical, 1. Januar bis 15. Juni 1906, S. 225f.

10 Zitiert nach: Angers-Artiste, Nr. 12, 21. Dezember 1889, S. 184.

Wegen Aufführungsmaterial wenden Sie sich bitte an Kalmus, Boca Raton.

Vincent d‘Indy

(b. Paris, 27 March 1851 – d. Paris, 2 December 1851)

Saugefleurie

Legend for orchestra after Robert de Bonnières (1884)

Biographical Background

The symphonic poem Saugefleurie is one of the French composer Vincent d’Indy’s early successes. He wrote it in 1884 at the age of thirty-three, having first considered taking up a military career. After serving in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71, he decided against this plan and in favor of music. To quote the composer’s diary entry of 26 September 1871, “Starting today, I would like to devote myself solely to art, to music, not only as a simple amateur, but as an artist; I make this resolution quite formally, and I shall not revoke it.”1 From then on he pursued his musical career with great determination. His friend and neighbor Henri Duparc brought him into contact with César Franck, with whom he took lessons in organ and composition (1873-75). D’Indy was never an official student at the Paris Conservatoire; instead, he preferred to study privately with Franck and sought his own opportunities for expanding his musical knowledge and skills. In 1873 he traveled to Franz Liszt in Weimar, where he spent two months in the circle of Liszt’s private pupils; he also accepted a position as titular organist at the Church of Saint-Leu-Traverny, played timpani at the Théâtre-Italien and the Opéra Comique, conducted the choir in the Concerts Pasdeloup and the Concerts Colonne, made public appearances as a pianist, and conducted concerts of amateur musicians. From 1876 he was active as secretary of the Société Nationale de Musique, which energetically furthered the performance of contemporary French and foreign composers in Paris. In the 1870s his own compositions began to reach public performance, such as the orchestral works La forêt enchantée (op. 8) and Wallenstein in the Parisian Concerts Pasdeloup. At the same time he undertook many journeys, traveling to Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany, and was very often seen at the Bayreuth Festival. In 1876 he attended the opening performances of Richard Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen, and in 1882 he made the personal acquaintance of the composer, whose music remained important to him to the end of his days. It was not until the 1880s that d’Indy became known to a broader public in Paris and France: his opéra comique Attendez-moi sous l’orme (op. 14) first drew attention to the thirty-one-year-old composer in 1882, and by 1885, when his légende dramatique Le Chant de la Cloche won the Prix de la Ville de Paris, he was considered one of the most promising composers of his generation.

Genesis, Première, Reception

Saugefleurie (op. 21) originated shortly before d’Indy’s artistic breakthrough at a turning point in his musical career. It was composed during the year 1884 and premièred at the Concerts Lamoureux in Château-d’Eau on 25 January 1885.2 The Concerts Lamoureux were a concert society founded by the violinist and conductor Charles Lamoureux in 1881. Lamoureux, the work’s dedicatee and, like d’Indy, an admirer of the music of Richard Wagner, conducted the earliest performances of Wagner’s music dramas in France. No detailed reviews of Saugefleurie’s première have come to light, but an account of the concert a few weeks later offers a sobering verdict: “Saugefleurie, given at the Concerts Lamoureux, is a wretched symphonic poem with a descriptive program; one can point out a few pretty timbral effects and ingenious harmonies unscrupulously snipped out of Wagner’s scores.”3 No documents on the work’s genesis survives, nor did d’Indy himself leave behind any accounts of the work or its première.

Though a reliable and comprehensive study of the work’s reception has yet to be undertaken, several performances of Saugefleurie make it logical to assume that that the piece was heard in concert with some regularity during d’Indy’s lifetime. On 22 December 1889 it was performed, perhaps for the first time outside Paris, in the Grand Concert Extraordinaire of the Association Artistique Angers.4 Several performances were given in the 1890s, for example in Nancy at a festival devoted to d’Indy’s music (1895).5 Even after the turn of the century Saugefleurie remained in the repertoire: it was heard at the Concerts Colonne on 19 November 19056 and at the tenth Conservatoire Concert in Nancy on 1 July of the following year, conducted by Guy de Ropartz.7 In 1907 d’Indy himself conducted it in Lyons at the seventh concert of the Société des Grands Concerts on 6 March, together with Istar and Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony.8 He also included Saugefleurie on the program of his American tour of 19069 – a clear indication that this early work maintained an important position among his compositions in his later years rather than being dismissed as a “sin of his youth.” In sum, Saugefleurie is neither one of the most nor the least successful of d’Indy’s works. This brief orchestral piece is thus probably still known in France.

The Literary Model and its Translation into Music

Saugefleurie is based on a poem from the fairy-tales of Robert de Bonnières. We reproduce the poem below:10

Alors vivat, sans crédit ni richesse,

Une fée humble et seule ........

............. Saugefleurie - -

Tel est son nom - - était charmante à voir.

Au bord d’un lac tout fleuri de jonquilles,

Elle habitait le tronc d’un saule creux

Et ne quittait son réduit ténébreux

Plus que ne font les perles leurs coquilles.

Mais, un beau jour que, chassant par le bois

Avec sa meute en superbe équipage,

Le Fils du Roi menait à grand tapage

Du bois au lac un dix-cors aux abois,

Pour voir les chiens et la belle poursuite

Et les pourpoints brillants des cavaliers,

Elle quitte son arbre ...........

Le Fils du Roi ..................

En voyant mieux un si charmant visage,

S’arrêta court et la dévisagea --

Sauge, sans plus se cacher dans les branches

En le voyant si beau, de son côté

Le regardait, devant elle arrêté,

Droit dans les yeux, de ses prunelles franches --

Naïf amour par pudeur s’enhardit :

Le fils du Roi baissa les yeux par contre.

...............................

Tous deux s’aimaient et ne s’étaient rien dit.

...............................

- - Aimer un homme était un cas de mort

Pour Sauge ....................

...............................

Sauge, pourtant, demeurait bouche close,

Et, de cela, ne voulait seulement

Qu’aimer le prince et mourir en l’aimant.

...............................

Or, nul pouvoir ne pouvait s’opposer

Au libre emploi de son gentil courage

Non plus qu’au choix de son premier baiser.

...............................

... Seigneur, les beaux jours sont comptés …

...............................

«N’aimez-vous point la belle solitude,

Et des amants n’est-ce plus l’habitude

De mieux s’aimer quand l’amour est secret?

Restons ici sans peur, si bon vous semble;

Nos yeux pourront se parler à loisir,

Et nous n’aurons de si charmant plaisir

Que seul à seul à demeurer ensemble.

Auprès de vous je sens mon coeur léger,

Légère est l’heure aussi qui me convie - -

O mon Seigneur, je vous donne ma vie...

Prenez-la donc, mais sans m’interroger!»

...............................

- - AMOUR et MORT sont toujours à l’affût

Ne croyez pas que celle que je pleure

Fut épargnée,

Elle sécha sur l’heure

Comme une fleur de Sauge qu’elle fut.

De Bonnières’ tale deals with a young fairy, Saugefleurie, who lives in seclusion in the trunk of a willow tree beside a woodland lake. One day she hears the sounds of the hunt: the son of the king is pursuing a stag through the woods. Transfixed by the sight of Saugefleurie, the prince comes to a stop. Although it is death for fairies to love a man, Saugefleurie chooses mortality in order to win the prince’s heart for a single moment. After a love scene she perishes: the final image in the poem compares her death with the wilting of a flower (sauge is French for sage).

For his musical setting, d’Indy takes two central themes from this narrative poem: Saugefleurie’s dreamlike melancholy and the hunt. The piece begins with an undulating theme in the divided cellos, its flowing rise and fall evoking the poem’s first image: Saugefleurie daydreaming alone on the shore of a lake, surrounded by blossoming flowers and rarely leaving her protective willow. It is probably no accident that the music resembles the Prelude of Das Rheingold, which d’Indy, a staunch Wagnerian, knew well. Soon a delightfully melodious theme arises in the solo viola (p. 6), later joined by the flute (p. 8). The contrast between the solo instruments, perhaps symbolizing the fairy, and the calm musical backdrop deftly evokes the image of Saugefleurie wandering aimlessly in the forest. The prince’s hunt is announced by a horn call (p. 10), this time with an undeniable similarity to Wagner’s Siegfried. After a romantic love scene the music comes full circle: the prince rides away with horn calls, and the fairy dies with the return of the opening viola melody, this time slightly more melancholy and sorrowful, with gloomier harmonies.

It would be worth examining precisely how d’Indy makes use of the orchestration and leitmotifs of Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen and to what extent this “legend for orchestra” follows in the footsteps of Franz Liszt’s symphonic poems and French program music.

Translation: Bradford robinson

1 Vincent d’Indy: Ma Vie, Journal de Jeunesse, Correspondance familiale et intime 1851-1931, ed. and annotated by Marie d’Indy (Paris, 2001), p. 143.

2 Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique (1885), p. 552.

3 La Revue Moderniste (April 1885), p. 50.

4 Angers Artiste, no. 12 (Saturday, 21 December 1889), title page.

5 Inferrable from an article by René d’Avril in Le Mercure Musical, no. 13 (1 July 1906), p. 40.

6 Louis Laloy: ‘Revue de la Quinzaine’, Le Mercure Musical (15 May – 15 December 1905), p. 584.

7 René d’Avril: ‘Revue de la Quinzaine’, Le Mercure Musical (1 July 1906), p. 40.

8 Revue française de musique (Lyons and Paris, 28 October 1906), p. 91, and (3 March 1907), p. 624.

9 Ch. M. L.: ‘Revue de la Quinzaine’, Le Mercure Musical (1 January – 15 June 1906), pp. 225f.

10 Quoted from Angers-Artiste, no. 12 (21 December 1889), p. 184.

For performance material please contact Kalmus, Boca Raton.