Robert Schumann

(b. Zwickau, June 8, 1810; d. Endenich, July 29, 1856)

Fünf Gesänge

op. 137

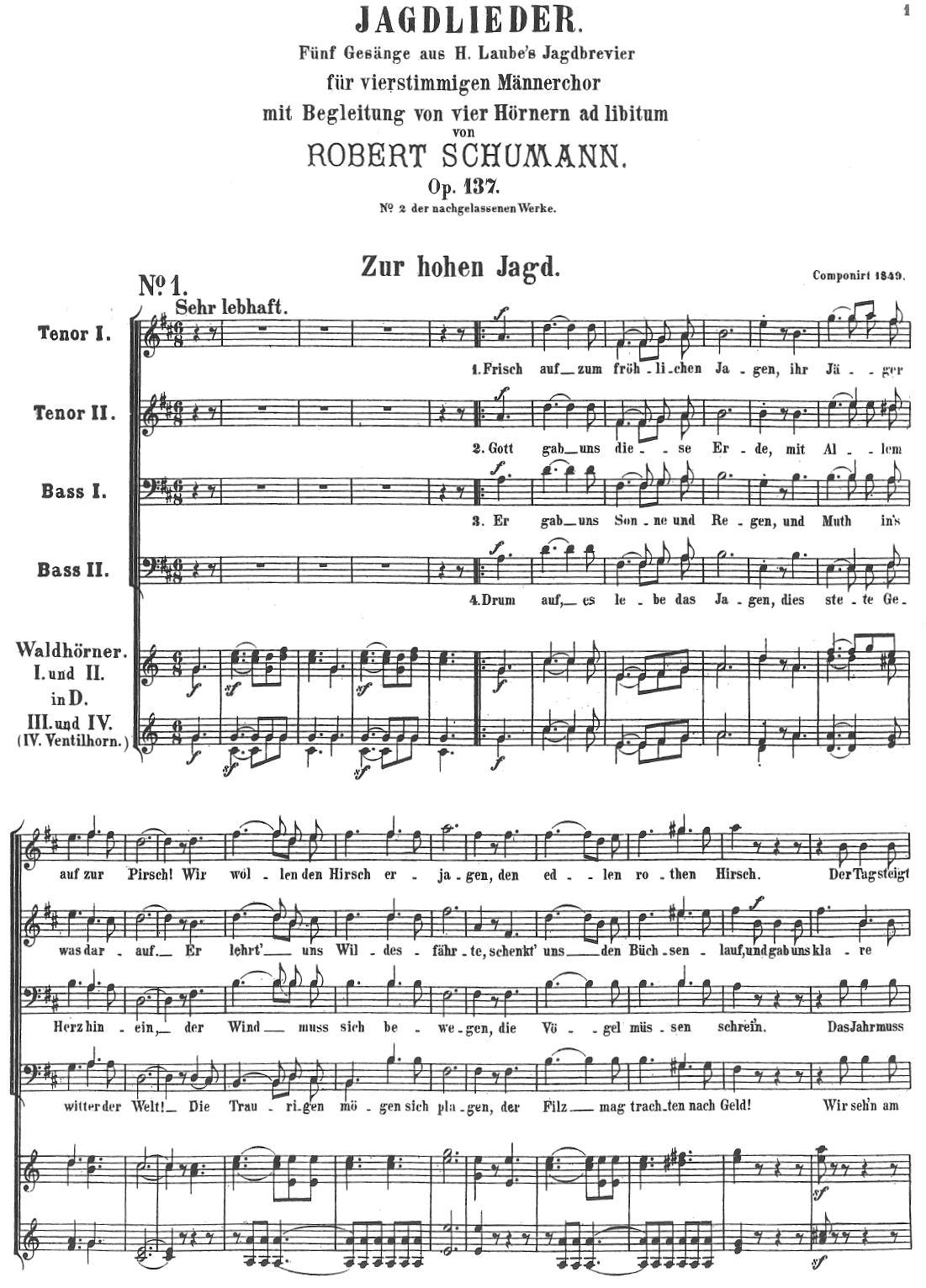

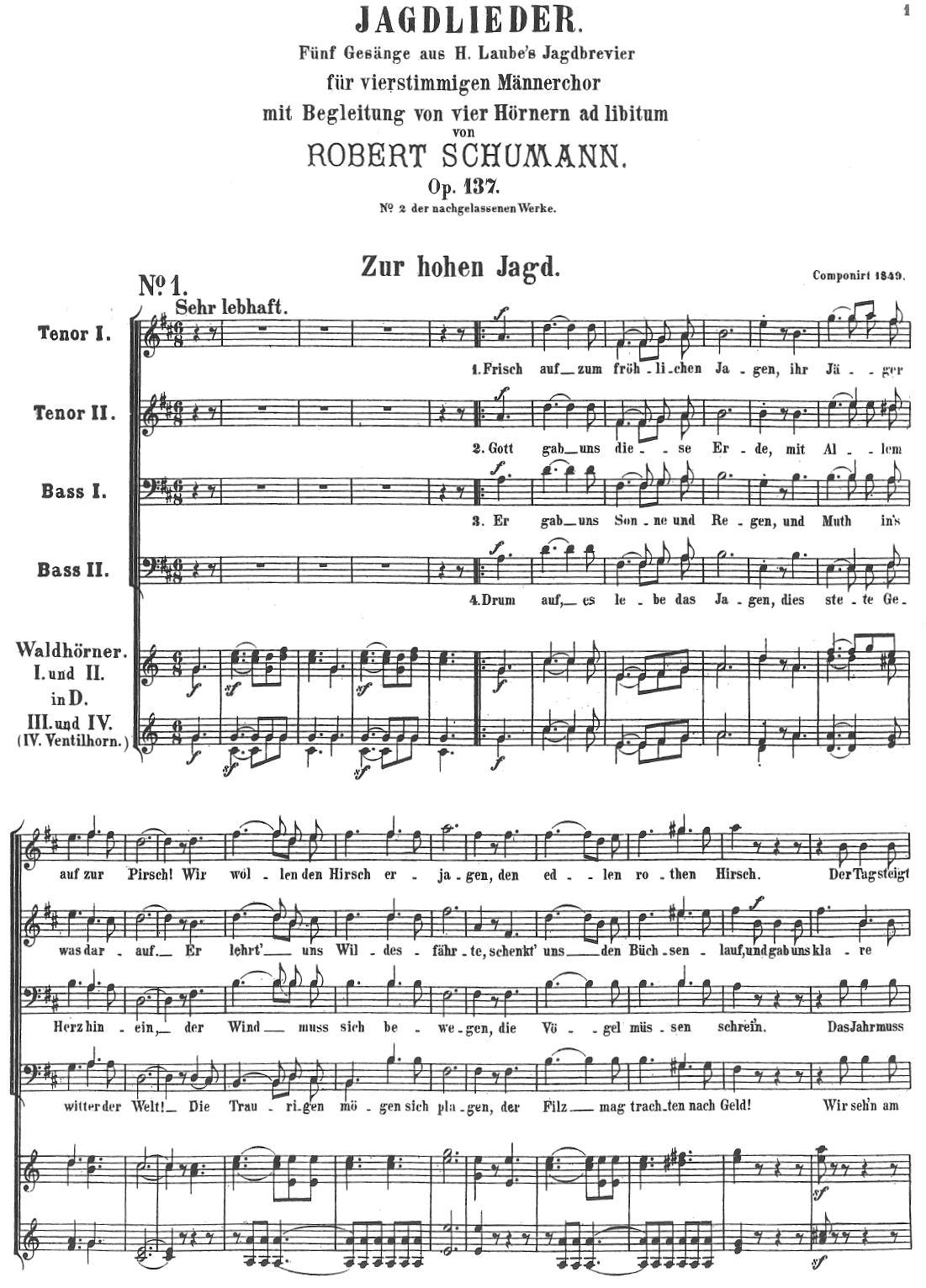

The Fünf Gesänge aus H. Laube’s Jagdbrevier (five songs from texts in the German dramatist and novelist Heinrich Laube’s ‘hunting guide’), for male voice chorus and four ad libitum horns is one of an array of the more eclectic late outputs by Robert Schumann (1810-1856), written in 1849, postdating the productive Liederjahr of 1840 that inaugurated the creative fecundity of the latter part of his life. John Daverio notes, however, that in a letter of 1848 to his close friend and contemporary the Dutch composer-conductor Johannes Verhulst (1810-1891) Schumann expressed his boredom with the typical Liedertafel sound that he had become intimately involved with when he assumed the directorship of the Dresden male voice group following Ferdinand Hiller’s departure in October 1847, and op. 137 proved to be among his last forays in the genre.1 Implicitly disowned by Schumann himself, op. 137 therefore invites an evaluation that relies purely on its own merits as a work or work cycle.

Though Laube’s texts in themselves appear uplifting and light in sentiment, they elicit from Schumann an at times almost ethereal sound, principally in the fourth piece, ‘Frühe’. In this connection we must remember that Schumann, perhaps much more than his contemporaries, participated in Maurice Blanchot’s formulation of Romantic literature as a ‘manifestation of itself to itself’2 in that he sees music as having this kind of literary function. For Schumann, music, like literature, is engaged in a ceaseless process of ‘showing’ that operates not through the medium of explicit characters (Schumann’s characters are implicit) but rather through characterization itself as the agency by which music achieves its effective meaning (though it is the tools of characterization – such as ciphers, correlations to personal diaries, and journalistic music criticism – that predominate in his work). It is from this standpoint that we may view his production of emotionally charged music to relatively innocuous texts: it is not the kind of text that counts per se, it is the fact that the presence of any text is a showpiece for the idea that music can, in a nonrepresentational way, do what literature does (and the linking of Schumann’s music with literary bases is so general that almost any piece of his, whether texted or not, seems to invite the listener to think narratively on very specific levels). ‘Frühe’ is distinguished from the rest of the set in tempo, texture and dynamic. It is therefore possible actually to begin an analysis of op. 137 by considering it, to build the analysis of the whole set around it. At the opening of the piece the horns have a truly soloistic function, serving both to articulate thematic material and to set the subsequent idiomatic vocal material (for example, the falling sevenths) in context.

Looking at these features alone illustrates that the break with the rest of the set is obvious, but the fact that, in the form of the set as a whole, the music is at this point plunged into an atmospheric literary moment (what Carolyn Abbate might conceive as an ‘unsung voice’),3 far from merely highlighting a different episode in the set, this point reveals its utter dependence on the real and conceptual integration of music and literature in a complex whole (one may say ‘music-as-literature’). The tonal instability generated in the imitative figure in the voices is closely followed by a plangent horn call (in both horns and voices), with alternating outward and inward contrary motions in the extreme parts, that leads into Neapolitan harmony. Taken together, these conditions fulfil the listener’s expectation that something different is happening. It now also seems puzzling that, if Schumann in general eventually rejected this male voice genre, he invested so much musicality and literary feeling in this piece (at least). The point is whether he subsequently felt he could only validate entrusting his more emotional musical writing to a more restricted range of genres, so could then this restriction indicate a narrowing of his aesthetic, a consideration that music could not simply be considered ‘as music’ in the sense of Wagnerian ‘absolute music’ (because of the limitations on genres that he considered expressive)? The sonority in ‘Frühe’ assists the strophic development of the thematic material, which is built on tonal suggestions and half-suggestions. The swelling, contemplative mood, to which the gently insistent rhythms contribute the core structure, is never dispelled, ensuring that the music never quite looks askance at the noble sentiments of the text (though the music also seems in some way typical of a genre). While this piece remains the one expressively (and chromatically) atmospheric movement in the set – like a Chopin nocturne, a Liszt reflection or a Bruckner Adagio – by virtue of its sound at one level it maintains its roots in and connections to what Daverio describes as ‘the republican overtones’ of Schumann’s works for male voice chorus.4 But these roots and connections cannot surpass its atmosphere, which is innate in the literary-minded Schumannesque harmonic language that is attached to the exhortatory text.

The other pieces in the set are, in general, texturally and rhythmically homogeneous essays in bright D-major or A-major tonalities (except the more reflective second piece, ‘Habet Acht!’). There is a D-major tonal unity to the set as a whole (from the opening and closing pieces and the related tonalities), which suggests larger-scale structural thinking on the level of a cycle rather than simply stand-alone pieces. The characteristic hunt fanfares in the horn parts at the outset of the first piece, ‘Zur hohen Jagd’, find echo elsewhere in the set, and their function is atmospheric – again, in a ‘literary’ way – rather than merely pictorial. This first piece, like the rest, does carry ‘republican overtones’ (for example, in the vocal parallel writing) but they occur in a context of tonal sophistication that, it seems, makes the listener think of a quasi-sonata form. The most interesting tonal twists that occur are the functional move to F♯ minor and the suggestions of diminished harmony in the latter part of the piece, in themselves stereotypical gestures, as to the genre, but adding a touch of colour to the potentially bland tonic harmony. Schumann cannot have felt very much inspired by the sort of word-painting exercise he seems to have been forced to make in respect of Laube’s relatively low-level text, but he continues to individuate the music with gestures that, while superficially seeming to be of a stock rhetorical repertory, remain his own creation with the purpose of lifting the whole setting beyond a mere tonic articulation. Schumann does achieve moments of rhythmic variation too, which mark structural points in the piece (especially structural cadences), and the rhythmic changes are accented by imitative writing (a pervasive feature because of the evoked hunt environment, but nonetheless subtle). Dynamic markings are discreet but exact – Schumann has seen that there is no need to overlay the texture with them, for the strictly musical elements are doing their work very well in order to convey the general atmosphere.

‘Habet Acht!’ constitutes the next most reflective movement after ‘Frühe’. It is very short and consists largely of evocative cadential gestures rather than more fully developed material. In dramatic terms, it has the function almost of a recitative between more mainstream movements. Because of the more concentrated form, dynamic markings play a more central structural role, giving more life to music which may otherwise have seemed somewhat rehearsed or formulaic. The dotted-rhythm hunting calls that had been characteristically announced in the first piece continue here too, and it is on this level not a surprising temptation to surmise that this kind of gesturing is why Schumann tired of the male voice chorus genre (that it admitted so easily of hackneyed representations like the hunt). The opening harmonies of the piece constitute one of Schumann’s oblique openings where the first gesture is not in what is apparently the home key of A minor, but in D minor. This does create an ambiguity in that the final cadence on A minor could be heard as a dominant of D minor (though C is naturalized). This is a delicious example, translated by Schumann, of what is sometimes a tonal ambiguity in open-intervalled horn calls. So the atmospheric work Schumann puts into the reflective quality of this second piece is generated at the tonal level (meaning that rhythmic interest is almost not required at all).

In the third piece, ‘Jagdmorgen’, marked ‘Frisch’, we are back to a more substantial formal presentation. Further individualistic harmonic writing occurs here, for example in an episode when Schumann turns the F♯ major dominant chord of B minor into a kind of false pivot chord of D major (first inversion), just before he uses staccato articulation at the cadence on D major. A hint of the kind of ambiguity discussed in the case of ‘Habet Acht!’ occurs if we consider the proximity of the B-minor tonal area to the end of the piece as giving the cadence on A major the quality of a dominant of D major (especially considering the relatively little time overall that the piece actually spends in A major). This tonal instability or inbuilt reluctance always to declare precise, continuous tonal allegiance is a hallmark trait in Schumann and one that is not erased even in his conventionalized work in a genre that he ultimately decided was not an ideal vehicle for his more poetic inspiration. As elsewhere in the set, the semi-contrapuntal texture is skilful rather than banal, and seems obviously made to increase whatever drama Schumann saw in Laube’s text that he wished to recreate at the musical level.

The patriotic final piece, ‘Bei der Flasche’, comes across as a slightly understated finale that consolidates the features of the rest of the set. Present again are the dotted rhythms, the imitative writing, and there are idiomatic tonic octave leaps at cadences to underscore the national sentiment and the characteristic male voice sound. Gone, however, is the heightened tonal adventurousness of earlier movements (though some diatonic quirks are still woven in here and there). The fifth strophe is set to a coda section, comprising about half the piece, that offers more tonic stability. This stability in itself may be evidence that Schumann thought structurally of these pieces as a set or cycle, since he may have wished definitively to reassert the tonic at the end not just of the final piece but of the cycle as a whole.

Before we can choose to begin to share the aesthetic judgement Schumann appears to have had on this sector of his creative output, which he apparently regarded as one of his compositional backwaters, we must recapitulate on the considerable dramatic investment he poses by his choice of unusual tonal moves, by his placement of a plangent slow piece quite close to the end of the cycle, and even by what we might regard as his ironic self-commentary through ‘music-as-literature’ on his own gestural borrowings to fit a genre that, at the end of the day, had to please audiences such as those in Dresden. On a superficial level, we can think that Schumann was not challenged by the commission of the Dresden Liedertafel to his care, and that he did not challenge himself in the music that he wrote for this ensemble. A central aesthetic question is, is the music written by a ‘great’ composer in a more ‘trivial’ genre (in terms of the forces and forms of the music) less characteristic of him or her than that which is written in the service of more ‘meaningful’ genres and topics? In Schumann’s case we can – and, more to the point, ought to – say that this would be an unsound assumption to embrace, not least because of the individuality of his musical style, an individuality that (taking into account its literary undercurrents of meaning) impresses perhaps more than most (or indeed all) other nineteenth-century composers.

Kevin O’Regan, 2013

1 John Daverio, Robert Schumann. Herald of a ‘New Poetic Age’ (Oxford and New York, 1997), pp. 397-398.

2 Maurice Blanchot, tr. Deborah Esch and Ian Balfour, ‘The Athenaum’, Studies in Romanticism 22 (1983), p. 162.

3 See Carolyn Abbate, Unsung Voices. Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, New Jersey, 1991).

4 Daverio, op. cit., p. 395.

For performance material please contact the publisher Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden. Reprint of a copy from the Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, München

Robert Schumann

(geb. Zwickau, 8. Juni 1810 - gest. Endenich, 29. Juli 1856)

Fünf Gesänge

op. 137

Fünf Gesänge aus H. Laubes Jagdbrevier für Männerchor und vier Hörner ad libitum ist ein Zyklus ekletischer Spätwerke Robert Schumanns (1810-1956). Im Jahr 1849 geschrieben, sind sie eine Rückbesinnung auf das produktive Liederjahr 1840, das Schumanns kreativen und fruchtbaren späte Jahre einläutete. Jedoch notiert John Daverio, dass Schumann in einem Brief aus dem Jahr 1848 an seinen engen Freund und Zeitgenossen, den niederländischen Komponisten und Dirigenten Johannes Verhulst (1810-1891), seinen Missmut über den typischen Liedertafel-Klang äußerte, mit dem er näher in Berührung kam, als er nach Ferdinand Hillers Abschied im Oktober 1847 die Leitung des Dresdner Männerchores übernahm. Op. 137 erwies sich als letzter Abstecher in dieses Genre.1 Durch Schumann selbst völlig verleugnet, lädt op. 137 daher zu einer Würdigung ein, die auf den Wert als Werk oder Werkzyklus baut.

Laubes Texte sind erbaulich und von leichter Natur, doch entlocken sie Schumann, besonders im vierten Stück Frühe, einen zuweilen fast ätherischen Klang. In diesem Zusammenhang müssen wir uns daran erinnern, dass Schumann, vielleicht mehr als seine Zeitgenossen, ein Befürworter von Maurice Blanchot’s These von der romantischen Literatur als „Manifestation vom Selbst zum Selbst“ 2 war , indem er Musik eine literarische Funktion zuschreibt. Für Schumann ist Musik wie Literatur ein Teil des endlosen Prozess des „Zeigens“, jedoch nicht mit Hilfe eindeutig beschriebener Charaktere (Schumanns Charaktere sind unausgesprochen), sondern durch deren Charakterisierung, die der Musik Bedeutung verleiht (obwohl es eher die Mittel der Charakterisierung sind wie etwa Chiffren, Beziehungen zu persönlichen Tagebüchern und journalistische Musikkritik, die in seinem Werk vorherrschen). Aus dieser Perspektive können wir seine Produktion hochemotionaler Musik zu harmlosen Texten betrachten. Wobei die Art des Textes von geringer Bedeutung ist; vielmehr demonstriert allein schon das Vorhandensein eines Textes, wie Musik auf abstrakte Weise das vollbringt, was auch Literatur macht (und die Verbindung von Schumanns Musik mit Dichtung ist so durchgängig, dass fast jedes Stücke – mit oder ohne Text– den Hörer einzuladen versucht, narrativ zu denken).

Frühe unterscheidet sich von den übrigen Stücken des Werkes in Tempo, Struktur und Dynamik. Daher ist es vorstellbar, eine Untersuchung von op. 137 von dort aus zu beginnen und die Analyse des Zyklus um dieses Stück herum aufzubauen. In der Einleitung dieses Gesangs ist die Funktion der Hörner tatsächlich solistisch, sowohl um das thematische Material vorzustellen als auch um das idiomatische Gesangsmaterial (zum Beispiel die fallende Septime) in den Zusammenhang des Stücks zu verankern. Wenn man sich diese Merkmale vor Augen führt, wird der Bruch mit dem Rest des Zyklus offensichtlich. Die Tatsache aber, dass gerade an dieser Stelle die Musik in einen atmosphärischen, erzählerischen Moment hineinstürzt (was Carolyn Abbate als eine „ungesungene Stimme“3 bezeichnen würde), zeigt deren Abhängigkeit von der realen und konzeptionellen Integration von Musik und Literatur in das komplexe Ganze. Auf die tonale Instabilität, die durch die imitierende Figur in den Singstimmen verursacht wird, folgt ein schallender Hornruf (in den Hörnern und den Singstimmen) in wechselnden entgegengesetzten Bewegungen in extremer Lage, die in einen Neapolitaner münden. Zusammengefasst: diese Verhältnisse erfüllen die Erwartung des Hörers, dass etwas Unerwartetes geschieht. Man fragt sich, warum Schumann trotz seiner kritischen Einstellung gegenüber Männerchören so viel musikalisches und literarisches Feingefühl in dieses Stück einbrachte. Vielleicht befürchtete er, dass man ihn nur anerkennen würde, wenn er seine emotionale Kompositionsweise auf ein begrenztes Repertoire an Gattungen anwenden würde, auch wenn dies eine Einengung seiner Ästhetik bedeutet – ein Gedanke, der vielleicht der Einsicht entspringt, dass Musik nicht einfach nur Musik im Sinne von Wagners „absoluter Musik“ ist. Der Klang in Frühe unterstützt die strophische Entwicklung des thematischen Materials, das auf tonalen Andeutungen basiert. Die sich steigernde, besinnliche Stimmung, die auf sanft insistierenden Rhythmen beruht, wird nie aufgelöst und garantiert, dass die Musik zu keiner Zeit die edle Gesinnung des Textes missachtet, obwohl sie gleichzeitig genretypisch ist. Während dieses Stück der einzige expressive und chromatische gefärbte, atmosphärische Satz ist – ähnlich einer Nocturne von Chopin, einer listzschen Betrachtung oder des brucknerschen Adagio – so bewahrt es dank seines Klanggeschehens seine Wurzeln und die Verbindung zu etwas, dass Daverio als die „republican overtones“ in Schumanns Männerchören beschreibt.4 Diese Wurzeln und Verbindungen bleiben jedoch immer der Atmosphäre untergeordnet, die für die literarisch beeinflusste schumannsche Harmonik, die den ermahnenden Text ergänzt, charakteristisch ist.

Die weiteren Stücke dieses Opus sind strukturell und rhythmisch homogene Abhandlungen in hellem D- oder A-Dur (ausgenommen das eher besinnliche zweite Stück Habet Acht!). D-Dur (in den beiden äußeren Stücken) einschließlich der verwandten Tonarten kann als integrierende Tonart des gesamten Opus angesehen werden. Die Auffassung, dass Schumann eher an einen Zyklus dachte denn an eine Sammlung von einzelnen Stücken, ist naheliegend.

Die charakteristischen Jagd-Fanfaren der Hörnern zu Beginn des ersten Stückes Zur hohen Jagd kehren auch später wieder und haben eine eher atmosphärische (erneut in „literarischer“ Weise) als nur bildhafte Funktion. Das erste Stück präsentiert wie die anderen auch „republican overtones“ (z.B. in der Parallelität der Singstimmen), eingebettet jedoch in eine tonal raffinierte Umgebung, dass es scheint, der Hörer solle zum Nachdenken über eine Quasi-Sonatenform angeregt werden. Die interessantesten tonalen Wendungen sind die harmonische Bewegung nach fis-Moll sowie die Andeutung verminderter Harmonik im letzten Teil des Stückes. Es handelt sich um stereotype Merkmale, aber sie bringen einen Hauch von Farbe in die fade grundtönige Harmonie. Schumann konnte sich von dieser Art wortmalerischer Übung nicht inspiriert gefühlt haben; es scheint, dass er sich angesichts Laubes wenig bedeutsamen Textes zu solchem Vorgehen gezwungen sah, jedoch individualisierte er die Musik mit Gesten, die, obwohl oberflächlich stereotype Floskeln, seine ureigene Schöpfung bleiben mit dem Ziel, einer reinen Grundtönigkeit zu entkommen. Auch kreiert Schumann Momente rhythmischer Variation, die zugleich Gliederungspunkte des Stückes darstellen (besonders in den Kadenzen) und betont Rhythmuswechsel durch Imitationen (ein durchgängiges, gleichwohl wenig subtiles Merkmal, inspiriert durch das Jagd-Themas). Dynamische Markierungen sind dezent, aber exakt – Schumann schien es nicht für notwendig zu halten, die Struktur damit zu überdecken, da die grundsätzlichen musikalischen Parameter genügten, um die Atmosphäre zu vermitteln.

Habet Acht! ist nach Frühe das am meisten reflektierende Stück. Es ist sehr kurz und enthält größtenteils plastische Kadenz-Gesten statt vollständig entwickeltes Material. Dramaturgisch gesehen hat das Stück die Funktion eines Rezitativs zwischen den anderen Sätzen. Wegen der sehr konzentrierten Struktur spielen dynamische Anweisungen eine größere Rolle, verlebendigen die Musik, die ansonsten irgendwie geprobt oder formelhaft erscheint. Der punktierte Rhythmus der Jagdrufe, die schon im ersten Stück charakteristisch waren, wird ebenfalls fortgesetzt, und es liegt nahe, dass es diese Art von Gesten sind, die Schumann am Männerchor, der sich so leicht abgenutzter Darstellungen wie der Jagd bedient, ermüdeten. Die eröffnenden Harmonien des Stückes stellen eine von Schumanns versteckten Eröffnungen dar, in denen die erste Bewegung nicht – was offensichtlich wäre – die Grundtonart a-moll ist, sondern d-Moll. Daraus ergibt sich eine Doppeldeutigkeit, in der die abschließende Kadenz in a-Moll als Dominante von d-Moll (obwohl das c aufgelöst ist) gehört werden kann. Das ist ein vorzügliches Beispiel für tonale Doppeldeutigkeit in offen - intervalligen Hornrufen. So wird die Arbeit an der Atmosphäre, die Schumann in die besinnliche Qualität dieses zweiten Stückes investiert, auf tonaler Ebene erzeugt (was bedeutet, dass rhythmisches Interesse kaum erforderlich ist).

Im dritten Stück Jagdmorgen, mit Frisch bezeichnet, kehren wir zurück zu einer strukturierteren Form. Hier findet sich erneut individuelle Harmonisierung, wenn Schumann z.B. in einer Episode die Fis-Dur-Dominante von h-Moll in einen falschen Umkehrungsakkord von D-Dur (erste Umkehrung) wendet, kurz vor einem staccato in einer Kadenz nach D-Dur. Eine Ahnung der Doppeldeutigkeit, wie sie im Fall von Habet Acht! diskutiert wurde, findet sich, wenn wir die Nachbarschaft des h-Moll-Tonraums am Ende des Stückes als ein Mittel verstehen, der A-Dur-Kadenz die Qualität einer Dominante von D-Dur zu geben. (Vor allem wenn man die relativ kurze Zeit bedenkt, die das Stück sich in A – Dur bewegt). Diese tonale Instabilität oder eingebaute Abneigung gegen stete Präzision und fortwährende tonale Bindung ist ein Charakterzug Schumanns, den er auch in einem Genre beibehielt, das er als eigentlich ungeeignet für seine poetischen Inspirationen erachtete. Wie anderswo in dem Opus ist die semi-kontrapunktische Struktur gekonnt und nicht banal und scheint offensichtlich Schumann ermöglicht zu haben, den dramatischen Gehalt von Laubes Text zu erhöhen, den er musikalisch nachbilden wollte.

Das patriotische letzte Stück Bei der Flasche kommt als leicht untertriebenes Finale daher, das die Qualitäten der übrigen Stücke des Opus festigt. Erneut sind punktierter Rhythmus, Imitationen und idiomatische Oktavsprünge in Kadenzen zu finden, die die nationale Sentimentalität und den charakteristischen Klang eines Männerchors unterstreichen. Dagegen ist die tonale Gewagtheit der ersten Sätze verschwunden – obwohl hier und da einige diatonische Extras eingeflochten sind. Die fünfte Strophe ist als Coda vertont, sie umfasst die Hälfte des Stückes und bietet mehr tonale Stabilität. Diese Stabilität selbst mag der Beweis dafür sein, dass Schumann strukturell die einzelnen Stücke als einen Zyklus verstand, denn er wird sich wohl gewünscht haben, die Tonika am Ende nicht nur als Schluss des Stückes, sondern auch als Schluss des gesamten Zyklus hervorzuheben.

Bevor wir uns fragen, ob wir Schumanns ästhetisches Urteil über einen Teil seines Schaffens teilen wollen, den er offensichtlich als ein kompositorisches Nebengewässer betrachtete, müssen wir den erheblichen dramatischen Aufwand rekapitulieren, mit dem er durch seine Wahl unüblicher tonaler Bewegungen, durch die Platzierung eines getragenen Stückes gegen Ende des Zyklus und ironische Selbstkommentare das Werk einem Genre anpasst, das schliesslich einer Hörerschaft wie jener in Dresden gefallen sollte. Oberflächlich gesehen wurde Schumann weder vom Auftrag der Dresdener Liedertafel herausgefordert noch forderte er sich selbst heraus. Die zentrale ästhetische Frage ist, ob Musik eines „großen“ Komponisten für eine eher „triviale“ Gattung (hinsichtlich Kraft und Form der Musik) weniger charakteristisch für ihn ist, als das, was er im Dienste „bedeutender“ Genres schuf. In Schumanns Fall können und sollten wir sagen, dass dies eine unseriöse Vermutung ist, nicht zuletzt wegen seines individuellen musikalischen Stils -, einer Individualität, die vielleicht mehr beeindruckt als die meisten (oder tatsächlich alle) anderen Komponisten des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Kevin O’Regan, 2013

1 John Daverio, Robert Schumann. Herald of a `New Poetic Age´. Oxford und New York 1997, 397-398.

2 Maurice Blanchot, The Athenaum, ins Englische übersetzt von Deborah Esch und Ian Balfour, in: Studies in Romanticism 22 (1983), 162.

3 vgl. Carolyn Abbate, Unsung Voices. Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton 1991.

4 Daverio, a.a.O., S. 395.

Aufführungsmaterial ist vom Verlag Breitkopf und Härtel, Wiesbaden. zu beziehen. Nachdruck eines Exemplars der Musikbibliothek der Münchner Stadtbibliothek, München.