Christian Sinding

(b. Kongsberg, 11 January 1856 – d. Oslo, 3 December 1941)

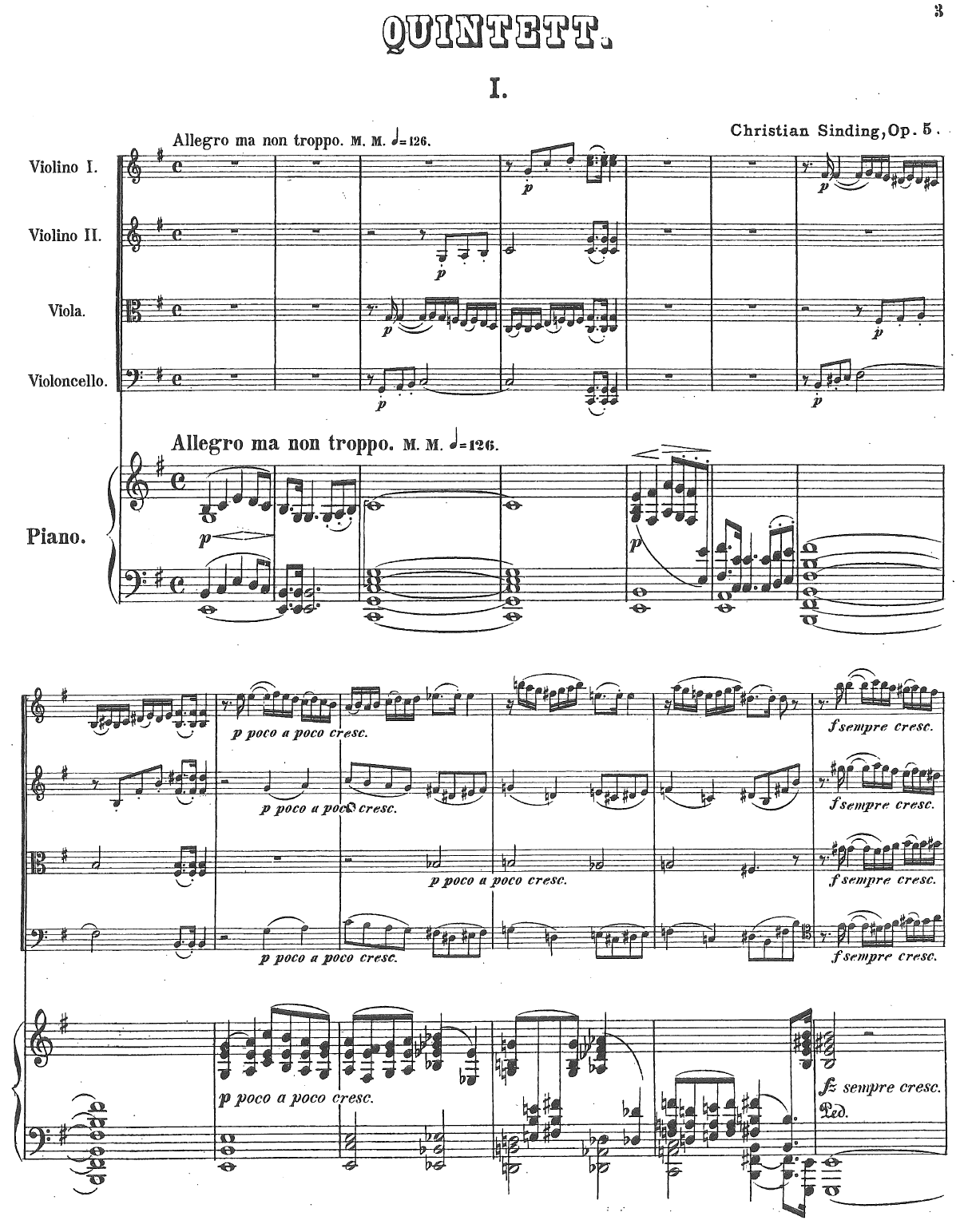

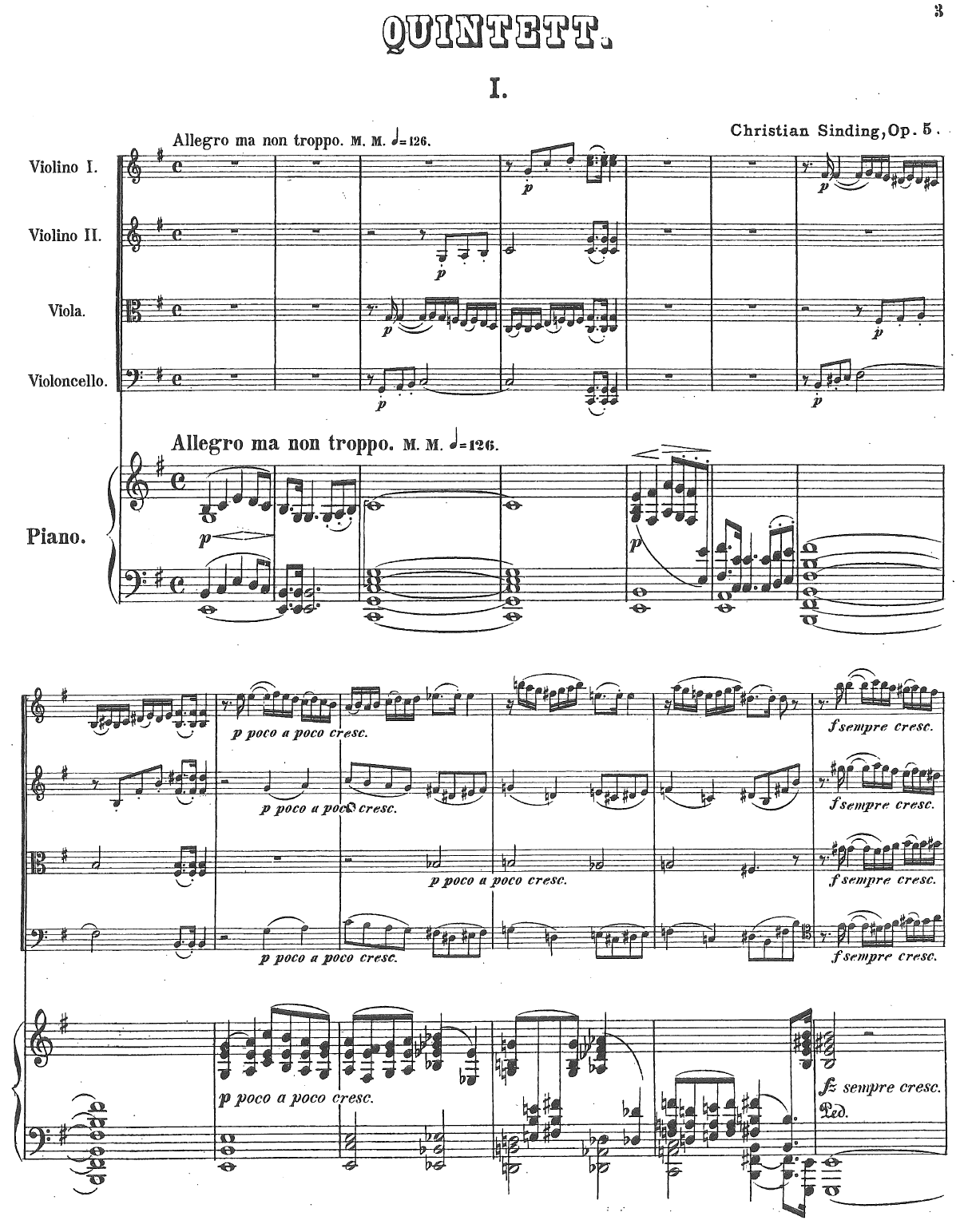

Piano Quintet in E minor, op. 5

Christian August Sinding (1856-1941) was an important and productive Norwegian composer whose compositional language remained all his life within the framework of nineteenth-century Romantic music. He was chiefly influenced by Austro-German masters, particularly Liszt, Wagner and Richard Strauss, and in terms of the history of Norwegian art music his music is typically seen as succeeding that of Edvard Grieg. His arguably most famous work, an evocative piece called Frühlingsrauschen (‘Rustle of Spring’) which is a staple of the piano repertoire, bears strong traces of Liszt in the passagework figurations and cantabile melody that they frame. Sinding’s dependence on the Austro-German tradition is not surprising given that, while still reputed in Norway, he spent a considerable part of his life in Germany, his first stay there being to study in Leipzig Conservatory at the age of eighteen. At the beginning of his musical career, Sinding was at first disposed to develop his talent for the violin, but in his initial Leipzig years this gave way to the pursuit of composition, following his self-recognition as well as others’ recognition of his own creativity in this area. The variety, volume and sometimes haunting invention of Sinding’s music earned him an international reputation, enough to see him invited to teach music theory and composition at the Eastman School of Music in New York for a year from 1920, for example. His reputation was certainly not lacking in his homeland, either, as he enjoyed continuous financial support and honours from the Norwegian government from 1880. Sinding’s oeuvre spans multiple genres with distinction, his best work being found equally in opera, symphonies, concertos, chamber and instrumental music, and songs. Kari Michelsen, in her article on Sinding in The New Grove 2, ascribes his posthumous decline both to a characteristic reaction against musical Romanticism and to the exaggerated status given to him during his lifetime by his peers. However easy it may be to accept this judgement as it stands, only a close examination of individual works can really show whether Sinding’s musical reputation has (if so) declined because of these factors and whether the character and quality of his works could mean that a decline in his reputation was or is not at all warranted in the first place.

The substantial, possibly even symphonic, Piano Quintet in E minor dates from Sinding’s German period. It was written in Munich between 1882 and 1884, at the point when he had committed himself full-time to composition. The length of the Quintet is achieved through the articulation of extended episodes that for their effect rely mainly on contrasts of tonality (though the rhythmic and harmonic contrasting of thematic material plays a significant part as well). Sinding’s manipulation of tonality often takes the form of unannounced shifts to tonal centres that are very proximate to yet very remote from the preceding tonality, for example the play generated by suddenly reiterating in G minor thematic material first stated in G♯ minor, in the Finale. Related to this is his practice of interruptive ascending semitonal transpositions, sometimes at cadential breaks. In a sense these kinds of moves (of which these are but two good examples) both support and avoid cliché, but, regardless of this, they certainly promote the characterization of his style as at times ‘post-Romantic’. In the Quintet there appear to be traces of Wagner and Bruckner, with, though not quite the tonal language of Richard Strauss, traces of pushing towards it. From just considering these observations, it seems that one of the most important analytical questions to be faced in any appraisal of Sinding’s music – particularly the instrumental music of his symphonies, concertos and chamber music – is whether his approach to and deployment of tonality is actually unique. To qualify this, we can say that every piece of music, even when operating within conventional formal patterns that to an extent govern tonal structure, embodies its own distinctive ‘take’ on the juxtaposition of tonalities, this element constituting an important component of the style of the piece. To that extent each piece is unique in this respect. For some repertoire, however, the stylistic difference or uniqueness achieved by harmony and tonality is such as to give it a greater prominence that singles out the individuality of the composer more than in other cases. It is with this criterion in mind that we must evaluate Sinding. If we choose to identify tonality as a principal technical element in his music, there is at least a strong possibility that we shall in fact come to the conclusion that his approach to it does uniquely distinguish his music, even if the tonal moves themselves can largely be seen as operating in the context of the more mainstream ‘great’ music of his Austro-German musical mentors.

The vast canvas of the Quintet falls into four movements, none of them less comprehensively treated than the others. There is a suspicion of thematic unity throughout the work, in certain occasional rhythmic similarities and fragmentary thematic recurrences across movements, but there appears to be no conscious monothematic procedure. The opening theme of the first movement, Allegro ma non troppo, sees a predominantly ascending and conjunct melody line coming to rest, in bar 3, on submediant harmony (in a minor key) (a characteristic shift for Grieg also). It is the piano that articulates the theme, the strings complementing with imitative thematic and decorative figuration. The texture is thicker from bar 9, with dramatic, dysfunctional chromatic harmony (relying on semitonal movement – see discussion above) set up from bar 10 leading to the E major chord, as the dominant of A minor, at bar 13. After a cadential flourish on the dominant, B major, we are by bar 20 now familiar enough with the main thematic content to appreciate its repetition and elaboration in the strings (from bar 21). Following a sonata structure, this elaboration is worked out, with the aid of features such as the interesting use from bar 41 of tied upbeats in the piano triplets, to a lyrical piano second theme in G major from bar 53 (which is abruptly and provocatively prefaced by the tenuto octave Eb, in the left hand, that is the tail of the preceding triplet ostinato, creating a disjunction over the first two beats of this bar). The sort of quirkiness evident in this whole bridging passage between minor first theme and relative major second theme indicates Sinding’s deliberate usage of harmonic and rhythmic irregularity in order to make his musical structure distinctive. Whether such irregularity is essential to his style or a more of a colouristic adjunct it may not be possible to tell definitely. This is part of the experience of listening to the Quintet: the piece effectively hides the exact significance of its musical gestures, so we are never sure what are its most typical features. For example, a detail such as the expanding (contrary-motion) chord progression in bars 89 and 90, at the end of the sonata exposition, is found in different forms elsewhere in the work, but the timing of its deployment in the music (of other sections of the work) is unpredictable. There are therefore frequent marginal frustrations of the expectations of listeners reared on a diet of chamber music of stricter formal pretensions. On this point, incidentally, we can note that Ferruccio Busoni, who studied in Leipzig a little later than Sinding and whose music and musical aesthetics envisaged elasticity of form and tonality, supported Sinding’s Quintet. Later, in his Entwurf einer neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst (1907), Busoni wrote: “Is it not singular, to demand of a composer originality in all things, and to forbid it as regards form? No wonder that, once he becomes original, he is accused of ‘formlessness’.” Though still a young (but very mature) musician himself at the time Sinding wrote his Quintet, Busoni, throughout his life a champion of emergent composers, must have recognized in the Quintet a subtle and appealing interplay of form and tonality that emphasized an individuality of style embodying precisely the quality of freedom Busoni cared to proclaim in his own music and writings on music.

The development section of the first movement begins at bar 104 following an ascending chromatic cadential sequence/flourish. The first and second themes are developed in chromatic and tonally remote variants. The recapitulation properly begins at bar 170 with the enunciation of the first theme in the first violin part. The second theme recurs at bar 222, in C major, getting another outing in E major from bar 238 (with piano figuration, corresponding to the repetition of the theme in the exposition, where it does not modulate). The faster coda begins from bar 264 and the whole movement is rounded off in semibreve bars, with a quirky absence of the tonic in the piano bass on the final chord (it being taken in the cello instead).

The Andante second movement offers quite a special sound. In this respect it is interesting that Delius was a close friend of Sinding, for the third movement of Delius’s String Quartet (1916) (Repertoire Explorer Study Score 1095) evokes a not dissimilar feeling. The mood is well set up by the chromaticism in the strings, which (particularly from bar 5) supports a plangent, soaring first violin melody. The whole effect is (until bar 17) even helped by the absence of the piano, which from the listener’s immediate memory frequently served a percussive function in the first movement. A second theme, which starts more quickly in the piano from bar 17, bears (from bars 21 to 27) a strong relationship to the elaboration of the first theme in the first movement (from bar 21 of the first movement). Further points of interest in the Andante movement include the added variety of constant triplet figuration, from bar 85, against the 4/4 time signature, first in the piano, then seeping into the strings. This procedure is so marked that at bar 133 the piano part unashamedly changes time signature from the rest of the texture, to 6/4, to accommodate a further subdivision of the triplets into more triplets, reverting back to 4/4 (at bar 145) only for a climactic extended V-I cadence in C major, upon which the music broadens out to Largamente. With echoes of both the opening themes (the soaring melody and the subsequent theme in the piano), the music approaches a muted, slow coda that abandons the piano for an atmospheric string sound. (Indeed the only non-supporting role of the piano writing in this movement is the provision of rhythmic interest – the piano has little independent material to say.) It would be really difficult to believe that Delius did not know Sinding’s Quintet, as his own aforementioned String Quartet has features in common with many of the ones just outlined here.

The third movement, Intermezzo, is a vigorous, extended movement in G major in which the piano comes into its own. A breezy folk-like ostinato quickly offers the opportunity of a virtuosic piano accompaniment. Following the initial statement, an astonishing passage, remarkable as much for the subtle rhythms in the piano part as for the unexpectedness of its tonal shifts, changes the mood from bar 73. After a return to the main theme, there is an appealing variant of it in Bb major at bar 318, stated in the piano. The movement works itself to a climactic finish, with the aid of devices such as piano tremolandi, the chromatic crescendo from bars 541 to 556 being redolent of Bruckner.

The complex rondo-like Finale, somewhat four-square in its rhythmic structure, adopts an epic tone and reprises themes from elsewhere in the work. It does contain material that is haunting for its beauty and simplicity, not surprisingly being dependent on the Norwegian folk context. The music is often unsubtle, with some extended, rhythmically monotonous passages and little sense of direction. However, of lasting interest is the chromatically conceived tonal structure, the folk episode in G♯ minor at bar 83 being reprised, at bar 480, in A minor. The opening theme of the Quintet recurs at bar 571, and the extended Allegro vivace coda from bar 579 incorporates some of the deliberately awkward yet stylistically distinctive and effective chromatic writing seen in the rest of the work.

It is easy to see why Sinding’s Piano Quintet helped cement his international reputation, and, from an analysis of it, easy to see how individualistic his music is (especially in its treatment of tonality). At its worst, it is only slightly bland, but at its best it is supremely interesting, memorable and subtle. In this light Sinding may not only be a (relatively) forgotten Norwegian master, but a forgotten Western European master.

Kevin O’Regan, 2013

Kevin O’Regan, 2013